Johnny66

Published 21 Jun 2015A well-considered documentary by the noted scholar, Dr Francis Pryor. The names Cerdic, Ceawlin, Cedda and Caedwalla are not exactly Germanic in origin? Cerdic’s father, Elesa, has been identified by some scholars with the Romano-Briton Elasius, the “chief of the region,” met by Germanus of Auxerre.

April 7, 2020

Britain AD: The Invasion That Never Was – The Anglo-Saxon Invasion (BBC Documentary)

Classics Summarized: Beowulf

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 28 Aug 2015Beowulf! The tale of the baddest Geat to ever Geat.

Tolkien said that the Dragon in Beowulf is one of only two *true* dragons in all of literature — the other being Fafnir. The influence of both these dragons is very visible in a lot of our more modern fantasy: for instance, where Beowulf’s Dragon inspired Smaug, o chiefest and greatest of calamities, Fafnir inspired C. S. Lewis to include that cursed bracelet thing that turned Eustace into a dragon in Voyage of the Dawn Treader. And I think we all know the badder of those two dragons, so I guess Tolkien — and, by extension, Beowulf — wins this round.

Where was I? Right. BEOWULFFFFF

PATREON: https://www.patreon.com/user?u=4664797

MERCH LINKS:

Shirts – https://overlysarcasticproducts.threa…

All the other stuff – http://www.cafepress.com/OverlySarcas…Find us on Twitter @OSPYouTube!

March 31, 2020

Third Crusade | 3 Minute History

Jabzy

Published 25 Jul 2015Thanks to Xios, Alan Haskayne, Lachlan Lindenmayer, William Crabb, Derpvic, Seth Reeves and all my other Patrons. If you want to help out – https://www.patreon.com/Jabzy?ty=h

February 29, 2020

The metallic nickname of Henry VIII

In the most recent Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes outlines the rocky investment history for German mining firms in England during the Tudor period:

Cropped image of a Hans Holbein the Younger portrait of King Henry VIII at Petworth House.

Photo by Hans Bernhard via Wikimedia Commons.

It’s an especially interesting case of England’s technological backwardness, given that copper was a material of major strategic importance: a necessary ingredient for the casting of bronze cannon. And it was useful for other industries, especially when mixed with zinc to form brass. Brass was the material of choice for accurate navigational instruments, as well as for ordinary pots and kettles. Most importantly, brass wire was needed for wool cards, used to straighten the fibres ready for spinning into thread. A cheaper and more secure supply of copper might thus potentially make England’s principal export, woollen cloth, even more competitive — if only the English could also work out how to produce brass.

The opportunity to introduce a copper industry appeared in 1560, when German bankers became involved in restoring the gold and silver content of England’s currency. The expensive wars of Henry VIII and Edward VI in the 1540s had prompted debasements of the coinage, to the short-term benefit of the crown, but to the long-term cost of both crown and country. By the end of Henry VIII’s reign, the ostensibly silver coins were actually mostly made of copper (as the coins were used, Henry’s nose on the faces of the coins wore down, revealing the base metal underneath and earning him the nickname Old Coppernose). The debased money continued to circulate for over a decade, driving the good money out of circulation. People preferred to hoard the higher-value currency, to send it abroad to pay for imports, or even to melt it down for the bullion. The weakness of the pound was an especial problem for Thomas Gresham, Queen Elizabeth’s financier, in that government loans from bankers in London and Antwerp had to be repaid in currency that was assessed for its gold and silver content, rather than its face value. Ever short of cash, the government was constantly resorting to such loans, made more expensive by the lack of bullion.

Restoring the currency — calling in the debased coins, melting them down, and then re-minting them at a higher fineness — required expertise that the English did not have. From France, the mint hired Eloy Mestrelle to strike the new coins by machine rather than by hand. (He was likely available because the French authorities suspected him of counterfeiting — the first mention of him in English records is a pardon for forgery, a habit that apparently died hard as he was eventually hanged for the offence). And to do the refining, Gresham hired German metallurgists: Johannes Loner and Daniel Ulstätt got the job, taking payment in the form of the copper they extracted from the debased coinage (along with a little of the silver). It turned out to be a dangerous assignment: some of the copper may have been mixed with arsenic, which was released in fumes during the refining process, thus poisoning the workers. They were prescribed milk, to be drunk from human skulls, for which the government even gave permission to use the traitors’ heads that were displayed on spikes on London Bridge — but to little avail, unfortunately, as some of them still died.

Loner and Ulstätt’s payment in copper appears to be no accident. They were agents of the Augsburg banking firm of Haug, Langnauer and Company, who controlled the major copper mines in Tirol. Having obtained the English government as a client, they now proposed the creation of English copper mines. They saw a chance to use England as a source of cheap copper, with which they could supply the German brass industry. It turns out that the tale of the multinational firm seeking to take advantage of a developing country for its raw materials is an extremely old one: in the 1560s, the developing country was England.

Yet the investment did not quite go according to plan. Although the Germans possessed all of the metallurgical expertise, the English insisted that the endeavour be organised on their own terms: the Company of Mines Royal. Only a third of the company’s twenty-four shares were to be held by the Germans, with the rest purchased by England’s political and mercantile elite: people like William Cecil (the Secretary of State) and the Earl of Leicester, Robert Dudley (the Queen’s crush). It was an attractive investment, protected from competition by a patent monopoly for mines of gold, silver, copper, and mercury in many of the relevant counties, as well as a life-time exemption for the investors from all taxes raised by parliament (in those days, parliament was pretty much only assembled to legitimise the raising of new taxes).

February 24, 2020

Norman Conquest of England | 3 Minute History

February 20, 2020

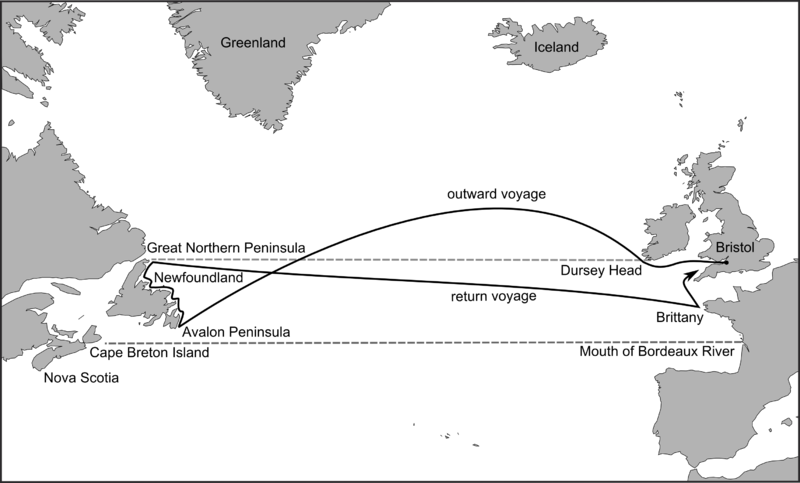

So that’s why John Cabot got hired!

Anton Howes explains something that I’d wondered about in the latest edition of his Age of Invention newsletter:

Route of John Cabot’s 1497 voyage on the Matthew of Bristol posited by Jones and Condon: Evan T. Jones and Margaret M. Condon, Cabot and Bristol’s Age of Discovery: The Bristol Discovery Voyages 1480-1508 (University of Bristol, Nov. 2016), fig. 8, p. 43.

Wikimedia Commons.

… in 1550 the English were still struggling with latitude. Their inability to find it, unlike their Spanish and Portuguese rivals, was one of the main things holding them back from voyages of exploration.

The replica of John Cabot’s ship Matthew in Bristol harbour, adjacent to the SS Great Britain.

Photo by Chris McKenna via Wikimedia Commons.The traditional method of navigation for English pilots was to simply learn the age-old routes. They were trained through repetition and accrued experience, learning to recognise particular landmarks and using a lead and line – just a thin rope weighted with some lead – to determine their location from the depth of the water. Cover the lead with something sticky, and you might bring up some sediment from the sea floor to double-check: a pilot would learn the kinds of sand and pebbles from to expect from different areas. And when they travelled out to sea, away from the coastline, they used a basic system of dead reckoning, taking their compass bearings from a known location, estimating their speed, and keeping in a particular direction for long enough. Or at least hoping to. They might keep track of their progress on a wooden traverse table, inserting pegs to indicate how far they had sailed, but it was ultimately a matter of rough estimation. Should they make any mistake — in terms of their speed, heading, or point of departure — they might easily get lost. But it was still a matter of trying to follow an already-known route. And English mariners of the 1550s did not even know that many routes.

For a voyage of exploration, by contrast, landmarks and sediment from the sea floor would be seen for the first time rather than recalled. By definition, there was no route to follow. So to launch their own voyages of discovery, the English needed to learn a new skill. They needed to look to the heavens.

Celestial navigation — measuring the altitude of heavenly bodies and then using geometry to determine one’s latitude on the earth’s surface — was by the 1550s already hundreds of years old. It had primarily been used to cross the deserts of North Africa and the Middle East — seas of sand, in which there might also be no landmarks from which to take bearings — and to navigate the Indian Ocean. Thus, while pilots in the Atlantic and the Mediterranean stuck to dead reckoning and soundings, Islamic navigators had for centuries used quadrants and astrolabes to take their bearings at sea. By the mid-fifteenth century, these instruments and techniques had found their way to Europe, where they were put to use especially by Portuguese, Spanish, and Italian explorers, along with additional instruments such as the cross-staff.

[…]

So for decades, English explorations relied on foreigners who either knew the routes that the English pilots didn’t, or who at least possessed the skill of mathematical, celestial navigation. The Italian explorer John Cabot (Zuan Chabotto), when he sailed to Newfoundland from Bristol in the late 1490s, was able to take latitude readings (he may even have been familiar with the older Islamic navigational practices, as he claimed to have visited Mecca). When Cabot died, the English expeditions that set out from Bristol in 1501-3 relied on Portuguese pilots from the mid-Atlantic islands of the Azores. And John Cabot’s son, Sebastian Cabot, who was involved in a few English expeditions, was so expert in mathematical navigation that he was eventually appointed pilot major for the entire Spanish Empire, making him responsible for the training and licensing of all its pilots — a position he held for three decades. When he led a voyage of exploration on behalf of Spain in 1526-30, a few English merchants became investors so that they could justify sending with him an English mariner, Roger Barlow, to secretly learn the Spanish routes across the Atlantic and have immediate knowledge if an onward route to Asia was discovered (as it turned out, South America got in the way).

February 18, 2020

Viking Invasion of England | 3 Minute History

Jabzy

Published 18 Oct 2016Thanks to Xios, Alan Haskayne, Lachlan Lindenmayer, Victor Yau, William Crabb, Derpvic, Seth Reeves and all my other Patrons.

February 8, 2020

The Trial of Charles I (1649)

Historia Civilis

Published 6 Feb 2020Join the Mailing List here: https://www.historiacivilis.com/

Patreon | http://patreon.com/HistoriaCivilis

Donate | http://www.paypal.com/cgi-bin/webscr?…

Merch | http://teespring.com/stores/historiac…

Twitter | http://twitter.com/HistoriaCivilis

Website | http://historiacivilis.comSources:

T. B. Howell “A Complete Collection of State Trials and Proceedings for High Treason and Other Crimes and Misdemeanors from the Earliest Period to the Year 1783,” Volume IV | https://bit.ly/2Q9tPOS

“The Sentence of the High Court of Justice upon the King,” January 27th, 1649 | https://bit.ly/2rooZVC

—

Diane Purkiss, The English Civil War: A People’s History | https://amzn.to/36YHkrb

Leanda de Lisle, White King: Traitor, Murderer, Martyr | https://amzn.to/2Qen9ir

Esmé Wingfield-Stratford, King Charles the Martyr: 1643-1649 | https://amzn.to/36XFvLg

Allan Massie, The Royal Stuarts: A History of the Family That Shaped Britain | https://amzn.to/2SonMZz

Michael B. Young, Charles I | https://amzn.to/35Jm9t7

John MacLeod, Dynasty: The Stuarts 1560-1807 | https://amzn.to/2MiJGt2

C. V. Wedgwood, The Trial of Charles I | https://amzn.to/372MDWy

Maurice Ashley, The House of Stuart | https://amzn.to/2PMvU42

Trevor Royle, Civil War: The Wars of the Three Kingdoms, 1638-1660 | https://amzn.to/2tKZNJP

Robert Ashton, The English Civil War: Conservatism and Revolution 1603-1649 | https://amzn.to/36WWOMz

J. P. Kenyon, The Civil Wars of England | https://amzn.to/2EIAJW3

Mark Kishlansky, A Monarchy Transformed: Britain 1603-1714 | https://amzn.to/371CSs0

Sean Kelsey, Politics and Procedure in the Trial of Charles I | https://www.jstor.org/stable/4141664

Clive Holmes, The Trial and Execution of Charles I | https://www.jstor.org/stable/40865689Music:

“Heliograph,” by Chris Zabriskie

“John Stockton Slow Drag,” by Chris Zabriskie

“Your Mother’s Daughter,” by Chris Zabriskie

“Hallon,” by Christian BjoerklundWe are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for us to earn fees by linking to Amazon.com and affiliated sites.

February 6, 2020

The rise of the Saadi Empire of Morocco

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes outlines the rise of a Morocco-based Islamic empire that beat the Portuguese and established a thriving smuggling network with England:

In 1500 you would have thought that Morocco’s golden ages were firmly in the past. The Portuguese in 1415 had conquered Ceuta, on the southern side of the Straits of Gibraltar, with minimal resistance. Over the next century they had then spread their influence across the Moroccan coastline, building forts, establishing small trading colonies, and interfering in local politics. Faced with constant raids, coastal towns like Safi, Massa, and Azammur submitted themselves to Portuguese vassalage in exchange for protection. And when local rulers failed to please them, the Portuguese installed new ones or even took direct control. A disunited Morocco was at the mercy of Portuguese colonial ambition — a source of grain destined for Portugal’s population, and of horses and patterned cloths for it to exchange in sub-Saharan Africa for gold and slaves.

In the 1510s, however, a new dynasty arose in Sus, in the south-west of the country, claiming direct descent from the Prophet Muhammad. These sharifs, the Saadi dynasty, began to fill the vacuum left by ineffective leadership from the sultans in Fez and Marrakech. And to address the massive power imbalance between themselves and the Portuguese, they began to cultivate sugar, selling it to other Europeans — Spanish, French, Genoese, Dutch, and English — in exchange for gunpowder weapons.

The English were especially expert smugglers, frequently able to sneak past the Portuguese fleets to where they could trade directly with the Saadis. Merchants from the Hanseatic league even approached the English government about using English mariners to get iron shot to Morocco. Their request was denied — Elizabeth I and her ministers were always careful never to explicitly allow the munitions trade, even in private letters, and often publicly disavowed it — but it was common knowledge among London’s merchants that the government supported the smuggling. This was partly about having a supply of sugar independent of Portuguese and Spanish control, but it was also a matter of national security. Because hidden among the sugar, marmalade, candied fruits, and almonds that the English transported from Morocco, were also copper and saltpetre — crucial materials for England’s own gunpowder weapons (I still haven’t quite worked out why England needed to import copper, given it had its own deposits in Cornwall, but it seems to have been important and a secure supply of saltpetre was definitely essential).

Both sides benefited from the arrangement. By the mid-1540s, the Saadis had bought the firearms and artillery necessary to take Marrakech and Fez, effectively unifying the country, and had earned sufficient wealth to buy the allegiance of the Moroccan population, providing grain during periods of intense famine. With that allegiance, they began isolating the Portuguese forts along the coastline, denying them access to food, workers, and trade. From the perspective of the Portuguese crown, the forts thus lost their economic value, while becoming increasingly expensive to maintain. Rather than providing Portugal with Moroccan grain, the forts increasingly needed grain from Portugal. With the added pressure of Saadi sieges, now aided by massive artillery, Portugal began to lose their footholds, abandoning many of the rest. Thus, in the space of a few decades, the export of sugar (and saltpetre) by the Saadis had put the mighty Portuguese empire on the back foot.

February 4, 2020

Anglo-Saxon Invasion | 3 Minute History

January 25, 2020

Refuting the pessimism of Malthus

In the latest edition of Anton Howes’ Age of Invention newsletter, he looks at the predictions of that old gloomy Gus, Thomas Malthus:

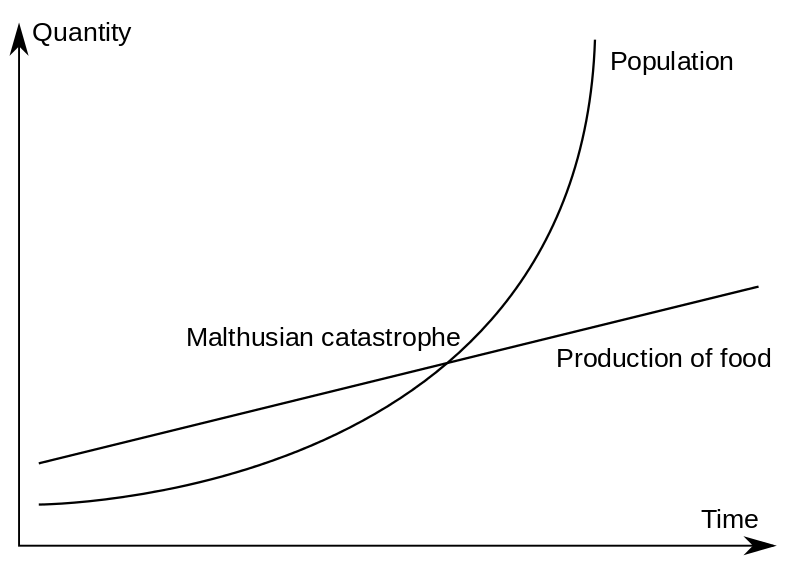

The Malthusian trap. For Malthus, as population increases exponentially and food production only linearly, a point where food supply is inadequate will inevitably be reached.

Graph by Kravietz via Wikimedia Commons.

For economies before the Industrial Revolution, population growth was an important and ever-present brake on prosperity — an observation most famously articulated by the Reverend Thomas Malthus. Writing at the end of the eighteenth century, he warned against the promises of improvement. Whereas the optimists looked at the acceleration of innovation around them and claimed infinite horizons for increasing living standards, Malthus pessimistically argued that population would always catch up. Although a new agricultural technology might briefly increase the amount of available food, the inexorability of population growth meant that it would soon be eaten up by extra mouths to feed. The population would end up larger than it was before the new technology, but with that population eventually no richer than it had been to begin with. Economic historians call this the Malthusian regime, or the Malthusian Trap.

Fortunately, Malthus’s pessimism would prove unfounded. Economy after economy has managed to escape the trap. British output had already been outpacing its population for two centuries by the time he was writing — England’s agricultural output alone had increased 171% while its population had grown 113% (not even taking into account the fact that it also increasingly relied on imported food, paid for by its other industries). And in the decades and centuries that followed, England’s output continued to shoot ahead, widening the lead. Output per capita rose and rose, to the extent that Malthus’s worries about overpopulation are now usually applied to resources other than food.

But while Malthus is famous for the theory, he wasn’t its inventor. Well before Malthus, the people who actually lived in the trap seem to have recognised its effects. Concerns about overpopulation may have led to the Garland or Flower Wars of the Aztec Empire and its neighbours: after a series of famines in the 1450s, the local states reportedly began to engage in ritual battles, with the losers captured and sacrificed to the gods. Still earlier, in ancient Greece, the young men of a settlement might be formally conscripted to go forth and colonise other islands and coastlines. They were typically banned from returning home for several years, and in at least one case slingers were posted on the shore to kill any of the colonists who tried to make a break for home. In a whole host of pre-industrial societies, “surplus” infants were often simply exposed to the elements.

By the sixteenth century, with the rise of print culture, Malthusian rationales were being clearly articulated. Here’s Richard Hakluyt writing in 1584, over two hundred years before Malthus:

Through our long peace and seldom sickness (two singular blessings of Almighty God) we are grown more populous than ever heretofore; so that now there are of every art and science so many, that they can hardly live one by another, nay rather they are ready to eat up one another.

It’s a direct statement of the Malthusian regime in action, expressed by one of England’s most influential Elizabethan intellectuals, and written specifically for the attention of the queen. Hakluyt thanked god for the recent and unusual lack of mass death, but now worried about overpopulation leading to low wages and unemployment. And he went on to list many other effects. Hakluyt argued that the misery would lead to unrest, thievery, begging, and “other lewdness”. The prisons filled up, where the poor either “pitifully pine away, or else at length are miserably hanged.”

January 24, 2020

The Arms and Armour of The English Civil War

Royal Armouries

Published 21 Dec 2017The Royal Armouries’ English Civil War collection boasts an array of infantry and cavalry arms and armour from the 1640s. Delve into this turbulent historical period with a look at some cavalry arms and armour.

Where to find us:

⚔Website: https://royalarmouries.org/home

⚔Blog: https://blog.royalarmouries.org/

⚔Twitter: https://twitter.com/Royal_ArmouriesThe Royal Armouries is the United Kingdom’s national collection of arms and armour. On this channel, discover what goes on behind the scenes at the museum and to see our collection come to life. From combat demonstrations to jousting coverage to behind the scenes tours with our curators, we’ve got it covered.

Have a question about arms and armour? Feel free to leave us a comment and we’ll do our best to answer it.

January 16, 2020

“… he returned to settle in a 250-year-old farmhouse in Wiltshire which he named ‘Scrutopia'”

In Quillette, Barbara Kay remembers Sir Roger Scruton:

Scruton’s breadth of knowledge was astonishing. None of his enemies could dispute that. He wrote whole books with complete authority on religion, architecture, opera, the environment, Islam, philosophy. But running through them all was a guilt-free love for, and fidelity to his — our — cultural inheritance. He loved his own home, England, and he would not repudiate it for its disfiguring historical warts, which seemed to preoccupy almost everyone else. It was Scruton who gave us the word “oikophobia” — hatred of one’s home — which is the hallmark of progressivism. He was out of sync with the hey-hey-ho-ho-western-civ-has-got-to-go zeitgeist. It didn’t help that he was the son of a lowly schoolmaster and had gone to the Royal Grammar School High Wycombe, a selective public high school.

Feeling isolated, like Andrew Sullivan and Christopher Hitchens before him, Scruton drifted “across the pond” to breathe the friendlier air of the last western redoubt where conservative thought finds a welcoming hearth. From 1992 to 1995, he taught a philosophy course at Boston University, and he spent a second stint in America from 2004 to 2009. But the pull of his beloved England proved too great, and he returned to settle in a 250-year-old farmhouse in Wiltshire which he named “Scrutopia.”

[…]

Among those who expressed their gratitude to Scruton in his final year were the governments of Poland and Hungary, who garlanded him with honors for the role he’d played in overthrowing the Communist regimes that had blighted their countries before the fall of the Berlin Wall. This recognition followed his receipt of the Czech Medal of Merit (First Class), presented to him by Vaclav Havel in 1998. At great risk to himself, Scruton had smuggled banned books across the Iron Curtain and helped dissidents organize an underground university, even arranging for degrees to be awarded by the Cambridge theology department. Among his other achievements, he was on the right side of history.

I cherish the memory of a brief conversation I had with Scruton after his Ottawa talk, in which he had expanded on the idea of decency, a concept of great interest and importance for me, especially in retrospect, for Scruton was himself a supremely decent man, although that did not save him from the postmodern jackals. I remember he said decency was easy to regulate in small towns, because you can’t be happy in a small town without a willingness to conform to standards. But these standards aren’t written down. There is no need. Everyone knows what they are. You know you’ve transgressed them when you receive disapproving glances or are cold-shouldered.

Compelled conformity — not legislated, God forbid, but enforced by social pressure — looks stifling to progressives, but in its own way it can be a great comfort, knowing the rules of what is and isn’t decent, and, through them, belonging. We all want to belong, but healthy belonging is sensitive to scale. We’re not made for globalization. We’re made for homes and homelands. If people don’t have homes to keep them rooted, feeling they belong in a good way, they will find fake homes that are tethered to ideas and theories, and then they often belong in a bad way. These are Scrutonesque musings.

Conformity and its effects, good and bad, absorbed Scruton. He once described the entire trajectory of his life as a constant movement toward “that impossible thing: an original path to conformity.” Like so many other of his gnomic utterances, it forces one to stop and think, really think, about what it means. And you know it means something worth thinking about because Roger Scruton never thought or spoke or wrote bullshit. He left that to his critics.

January 15, 2020

Hundred Years’ War: Battle of Crecy 1346

Kings and Generals

Published 7 December 2017The Hundred Years’ War of 1337-1453 between France and England is one of the most crucial conflicts in the history of Europe. It changed the social, political and cultural outlook of the countries involved, influenced the change in warfare, brought the end of feudalism closer. The first phase of this war is called the Edwardian War, and one of the most decisive engagements of this conflict was the battle of Crecy (1346). This series will have 5 videos, so don’t hesitate to like, subscribe and share. And if you want to support us, you can do it on Patreon: http://www.patreon.com/KingsandGenerals or Paypal: http://paypal.me/kingsandgenerals

We are grateful to our patrons, who made this video possible: Ibrahim Rahman, Koopinator, Daisho, Łukasz Maliszewski, Nicolas Quinones, William Fluit, Juan Camilo Rodriguez, Murray Dubs, Dimitris Valurdos, Félix Gagné-Dion, Fahri Dashwali, Kyle Hooton, Dan Mullen, Mohamed Thair, Pablo Aparicio Martínez, Iulian Margeloiu, Chet, Nick Nasad, Jeyares, Amir Eppel, Thomas Bloch, Uri Sternfeld, Juha Mäkelä, Georgi Kirilov, Mohammad Mian, Daniel Yifrach, Brian Crane, Muramasa, Gerald Tnay, Hassan Ali, Richie Thierry, David O’Hare, Christopher Commins, Chris Glantzis, Mike, William Pugh, Stefan Dt, indy, Bashir Hammour, Mario Nickel, R.G. Ferrick, Moritz Pohlmann, Russell Breckenridge, Jared R. Parker, Kassem Omar Kassem, AmericanPatriot, Robert Arnaud, Christopher Issariotis, John Wang, Joakim Airas, Nathanial Eriksen and Joakim Airas.

This video was narrated by our good friend Officially Devin. Check out his channel for some kick-ass Let’s Plays. https://www.youtube.com/user/Official…

The Machinimas for this video is created by one more friend – Malay Archer. Check out his channel, he has some of the best Total War machinimas ever created: https://www.youtube.com/user/Mathemed…

Inspired by: BazBattles, Invicta (THFE), Epic History TV, Historia Civilis and Time Commanders

Machinimas made on the Total War: Attila engine using the great Medieval Kingdoms mod.

Production Music courtesy of Epidemic Sound: http://www.epidemicsound.com

January 7, 2020

Wars of the Roses | 3 Minute History

Jabzy

Published 23 Jan 2015Of course there’s a lot I left out.

And when I say “Lancaster”, it sounds out of place because I had to just record over me continuously saying “Lancashire”.