In City Journal, Lance Morrow looks back at the successes and failures of President Wilson:

It’s been a century since President Woodrow Wilson arrived in Europe, weeks after the Armistice ending World War I. A crowd of 2 million cheered him in Paris. The papers called him the “God of Peace,” the “Savior of Humanity,” a “Moses from America.” He bowed, he tipped his silk top hat — the newsreel images come flickering to us from an earlier world. He sat down with Georges Clemenceau and David Lloyd George and the others to hash out the fiasco of the Versailles Treaty. He returned home to the fatal wrangle over the League of Nations with Henry Cabot Lodge in the Senate. Then came the cross-country tour to sell the treaty to the American people, his collapse on the train near Wichita, and, back in Washington, the terrible stroke and the long twilight — a sequence that led, further down the road, to Warren G. Harding and, in the fullness of time, to Adolf Hitler and World War II.

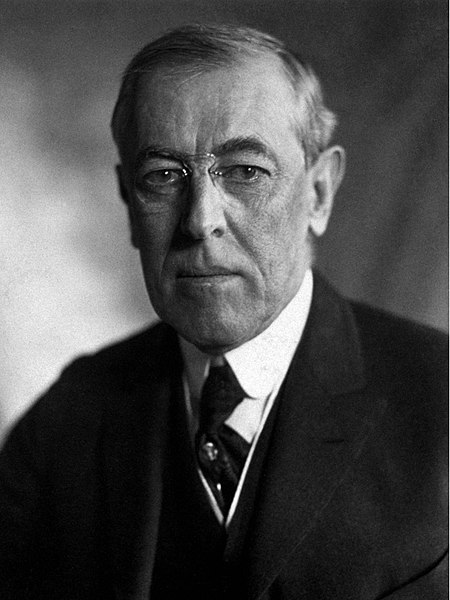

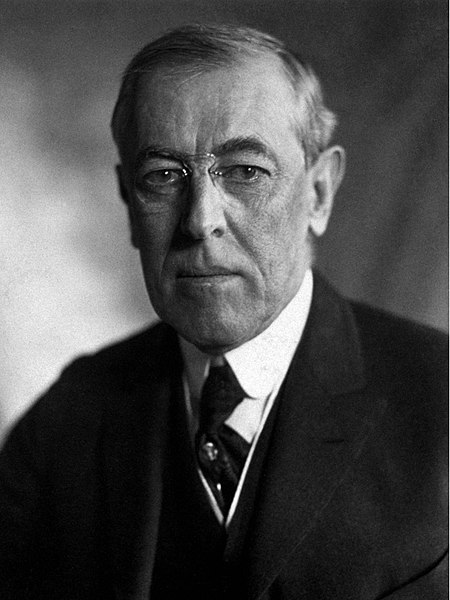

Woodrow Wilson, 1919

Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

The Woodrow Wilson story is an American classic — a set piece, like the rise and fall of Joseph McCarthy, or the fable of John F. Kennedy. Of Wilson, the historian Barbara Tuchman wrote: “Since Americans are not, by and large, a people associated with tragedy, it is strange and unexpected that the most tragic figure in modern history — judged by the greatness of expectations and the measure of the falling off — should have been an American.”

People speak of “settled science.” One might also speak of “settled myth.” (The Kennedys are one of those.) But Wilson’s myth remains vexed and unsettled. He persists, in American memory, as a sort of botched paragon — a man who remains almost irritatingly alive and imperfect and somehow touching. The respect that he deserves is complicated — and so is the contempt. The same has been said of American idealism itself.

As with America, there are two basic versions of Wilson: the sacred and the profane. Was his greatness real or fake? He ranks in polls in the top quarter of American presidents, but with a dissenting asterisk. Was he the superbly effective Progressive president (who introduced the Federal Reserve and the graduated income tax and much else) and the prophet of twentieth-century internationalism? (Wait: Are we to thank Wilson for Vietnam? Iraq? Afghanistan?) Or was he the last fling of nineteenth-century moralism and hypocrisy — a Southern-born racist or near-racist, and a brute on the subject of civil liberties? (He tossed Eugene V. Debs in jail merely for disagreeing with him on the war, leaving it to Warren G. Harding to pardon Debs.) Some said that his mind was a Sunday school; others, that it was the pool of Narcissus. Yet he managed to be a great man all the same. It’s too bad that he did not leave the presidency, one way or another, in 1919, after the damage from his stroke became evident. Amazingly, even in the summer of 1920, the broken man had delusions of running for a third term. He felt embittered and betrayed when the Democratic nomination went to Governor James Cox of Ohio. Woodrow Wilson’s ego died harder than Rasputin.

An indispensable aspect of Wilson’s genius—and a key, perhaps, to his failure — was his lambent but vaguely narcissistic prose style, sweet in its clarities but sometimes too supple and manipulative. Unlike most presidents, he wrote his own speeches. He governed a good deal by means of language, and he used words to impose his will or to conjure up an ideal world that might be mistaken, from a distance, for the Kingdom of God. He was also a theatrical man, an actor, an excellent mimic: a performer. Was he Prospero? Or was he, in the end, Christ crucified? People spoke routinely of his messiah complex. At one point during the Paris Peace Conference, he seemed to suggest that he was actually an improvement on the messiah. Lloyd George listened in amazement as Wilson observed that organized religion had yet to devise practical solutions to the problems of the world. Christ had articulated the ideal, Wilson said, but he had offered no instructions on how to attain it. “That is the reason why I am proposing a practical scheme to carry out his aims.” Self-righteousness is tiresome in the end. Many concluded that Wilson should be remembered, without appeals to either religion or literature, as the stiff-necked, hypochondriacal son of a Presbyterian minister, led astray by his own moral vanity — either that, or as the uxorious hero of ladies’ teas. He loved the companionship of doting women but not necessarily that of strong men.

H.L. Mencken wrote of Wilson, shortly after the President’s death, in a review of The Story of a Style by Dr. William Bayard Hale:

Two or three years ago, at the height of his illustriousness, it was spoken of in whispers, as if there were something almost supernatural about its merits. I read articles, in those days, comparing it to the style of the Biblical prophets, and arguing that it vastly exceeded the manner of any living literatus. Looking backward, it is not difficult to see how that doctrine arose. Its chief sponsors, first and last, were not men who actually knew anything about the writing of English, but simply editorial writers on party newspapers, i.e., men who related themselves to literary artists in much the same way that Dr. Billy Sunday relates himself to the late Paul of Tarsus. What intrigued such gentlemen in the compositions of Dr. Wilson was the plain fact that he was their superior in their own special field — that he accomplished with a great deal more skill than they did themselves the great task of reducing all the difficulties of the hour to a few sonorous and unintelligible phrases, often with theological overtones – that he knew better than they did how to arrest and enchant the boobery with words that were simply words, and nothing else. The vulgar like and respect that sort of balderdash. A discourse packed with valid ideas, accurately expressed, is quite incomprehensible to them. What they want is the sough of vague and comforting words – words cast into phrases made familiar to them by the whooping of their customary political and ecclesiastical rabble-rousers, and by the highfalutin style of the newspapers that they read. Woodrow knew how to conjure up such words. He knew how to make them glow, and weep. He wasted no time upon the heads of his dupes, but aimed directly at their ears, diaphragms and hearts.

But reading his speeches in cold blood offers a curious experience. It is difficult to believe that even idiots ever succumbed to such transparent contradictions, to such gaudy processions of mere counter-words, to so vast and obvious a nonsensicality. Hale produces sentence after sentence that has no apparent meaning at all — stuff quite as bad as the worst bosh of the Hon. Gamaliel Harding. When Wilson got upon his legs in those days he seems to have gone into a sort of trance, with all the peculiar illusions and delusions that belong to a frenzied pedagogue. He heard words giving three cheers; he saw them race across a blackboard like Socialists pursued by the Polizei; he felt them rush up and kiss him. The result was the grand series of moral, political, sociological and theological maxims which now lodges imperishably in the cultural heritage of the American people, along with Lincoln’s “government for the people, by the people,” etc., Perry’s “We have met the enemy, and they are ours,” and Vanderbilt’s “The public be damned.” The important thing is not that a popular orator should have uttered such grand and glittering phrases, but that they should have been gravely received, for many weary months, by a whole race of men, some of them intelligent. Here is a matter that deserves the sober inquiry of competent psychologists. The boobs took fire first, but after a while even college presidents — who certainly ought to be cynical men, if ladies of joy are cynical women — were sending up sparks, and for a long while anyone who laughed was in danger of the calaboose. Hale does not go into the question; he confines himself to the concrete procession of words. His book represents tedious and vexatious labor; it is, despite some obvious defects, very well managed; it opens the way for future works of the same sort. Imagine Harding on the Hale operating table!