So how do you build a collection? What do you do once you’ve wandered off into the jazz section. What do you buy? Not only is there just so much … stuff, but it’s an ever-expanding world. I mean, even if you knew everything there was to know about jazz, how could you possibly own it all? There are nearly as many jazz albums as there are women in the world and how could you sleep with all of them? As with any other type of music, there are some classic records you’d be mad to ignore, but with jazz you really have to plough your own furrow. The jazz police are a proscriptive lot – look to them for recommendations and they’ll tell you that Norah Jones and Stan Getz aren’t jazz, that Blue Note shouldn’t have signed St Germain and that Dave Brubeck’s “Take Five” is only ever good for paint commercials. However, these are probably the same people who, 40 years ago, would have told you that Abba don’t make good pop music or that punk was a flash in the pan.

And there were some things I just didn’t get. Ornette Coleman was one. At the same time Miles Davis was breaking through with modal jazz forms, Coleman invented free jazz with The Shape Of Jazz To Come. Over half a century after the event it is difficult to recapture the shock that greeted the arrival of this record, but it just gave me a headache. Coleman played a white plastic saxophone that looked like a toy, he dressed like a spiv and was a master of the one-liner, the “Zen Zinger” (stuff like, “When the band is playing with the drummer, it’s rock’n’roll, but when the drummer is playing with the band, it’s jazz”), so I really wanted to like his music. But I couldn’t. No matter how much I tried. As far as I was concerned he was improvising up his own sphincter.

Dylan Jones, “The 100 best jazz albums you need in your collection”, GQ, 2019-08-25.

September 29, 2023

QotD: Collecting jazz

September 26, 2023

“Passport Bros”

Few online people are less tuned-in to the mainsteam zeitgeist than me, so perhaps I’m once again one of the last people to be clued-in about “passport bros”. Here’s Janice Fiamengo‘s post on the “bros” and the women who apparently spend a lot of time criticizing them:

Female commentary on so-called Passport Bros is not hard to find on the internet: women are angry, contemptuous, and incredulous that men are looking for women overseas and encouraging other men to do the same — not for sex tourism (which feminists loved to criticize until they discovered that women are doing it too, in which case it is acceptable), but for a long-term relationship, including, in many cases, marriage and children. These men will partially or entirely relocate to the women’s home country in order to start a new, non-western (and non-feminist) life. The angry internet women claim not to care personally: let the losers go is their expressed attitude. Yet the sheer number and vehemence of their responses suggests they do care.

The angry commentary follows a standard pattern in which the women claim to know why a significant minority of men are giving up on western women as mates. The reason never has anything to do, of course, with faults in western women or their unrealistic expectations […]

Likewise, the reason never has anything to do with western divorce laws — in which a man can be ejected from his home, imprisoned, forced to undergo a psychiatric exam, fleeced, and deprived of his children by a grasping ex-wife — or with the fact that women are the ones who initiate divorce in upwards of 70% of cases (and are often applauded for doing so).

The reason has nothing to do with women’s openly expressed attitudes of superiority, resentment, and anti-male bigotry, which are rampant in western cultures, especially Anglophone ones. It has nothing to do with the #MeToo/Believe Women climate of baseless accusation that regularly sees men accused and disgraced purely on a woman’s say-so. It has nothing to do with the institutionalized discrimination of “equity” hiring that makes it difficult for men to find and advance in careers in order to be acceptably successful to the kind of women who now deride them for their failure.

According to the angry women online, men are leaving the west (particularly North America) to find partners because they aren’t good enough for western women. The men are allegedly “terrible, and don’t want to stop being terrible”, according to one gleefully irate commentator. Their only chance is with women so poor as to be grateful for a “terrible” man; in return, such women will have to “subject themselves to [his] advances”, according to another critic’s Victorian-style phrasing.

[…]

Many such women — protected by our pro-woman culture and deferred to by men terrified of female wrath — reach adulthood without ever having received any serious criticism. If and when they are criticized, their response is a howl of outrage and wounded self-regard. This is precisely what is happening in reaction to the Passport Bros.

Underneath the anger, there is perhaps a hint of fear. It’s not fear that men will leave the west in droves (they don’t see that happening yet, and neither do I), but it’s fear that men are not, after all, entirely under female control. Not yet, and maybe never. Some men are sick of the anti-male abuse and starting to do something about it. They are critically examining women’s characters and attitude; they’re drawing back from the acquiescence they’ve always been expected (and been willing) to give. Some are walking away and telling other men to do the same.

These women are used to dishing out the denunciation, reveling in justified grievance; they are infuriated to find that now they are the ones being judged and found wanting.

Don’t be that girl.

September 23, 2023

More on the history field’s “reproducibility crisis”

In the most recent edition of the Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes follows up on his earlier post about the history field’s efforts to track down and debunk fake history:

The concern I expressed in the piece is that the field of history doesn’t self-correct quickly enough. Historical myths and false facts can persist for decades, and even when busted they have a habit of surviving. The response from some historians was that they thought I was exaggerating the problem, at least when it came to scholarly history. I wrote that I had not heard of papers being retracted in history, but was informed of a few such cases, including even a peer-reviewed book being dropped by its publisher.

In 2001/2, University of North Carolina Press decided to stop publishing the 1999 book Designs against Charleston: The Trial Record of the Denmark Vesey Slave Conspiracy of 1822 when a paper was published showing hundreds of cases where its editor had either omitted or introduced words to the transcript of the trial. The critic also came to very different conclusions about the conspiracy. In this case, the editor did admit to “unrelenting carelessness“, but maintained that his interpretation of the evidence was still correct. Many other historians agreed, thinking the critique had gone too far and thrown “the baby out with the bath water“.

In another case, the 2000 book Arming America: The Origins of a National Gun Culture — not peer-reviewed, but which won an academic prize — had its prize revoked when found to contain major errors and potential fabrications. This is perhaps the most extreme case I’ve seen, in that the author ultimately resigned from his professorship at Emory University (that same author believes that if it had happened today, now that we’re more used to the dynamics of the internet, things would have gone differently).

It’s somewhat comforting to learn that retraction in history does occasionally happen. And although I complained that scholars today are rarely as delightfully acerbic as they had been in the 1960s and 70s in openly criticising one another, they can still be very forthright. Take James D. Perry in 2020 in the Journal of Strategy and Politics reviewing Nigel Hamilton’s acclaimed trilogy FDR at War. All three of Perry’s reviews are critical, but that of the second book especially forthright, including a test of the book’s reproducibility:

This work contains numerous examples of poor scholarship. Hamilton repeatedly misrepresents his sources. He fails to quote sources fully, leaving out words that entirely change the meaning of the quoted sentence. He quotes selectively, including sentences from his sources that support his case but ignoring other important sentences that contradict his case. He brackets his own conjectures between quotes from his sources, leaving the false impression that the source supports his conjectures. He invents conversations and emotional reactions for the historical figures in the book. Finally, he fails to provide any source at all for some of his major arguments

Blimey.

But I think there’s still a problem here of scale. It’s hard to tell if these cases are signs that history on the whole is successfully self-correcting quickly, or are stand-out exceptions. I was positively inundated with other messages — many from amateur historical investigators, but also a fair few academic historians — sharing their own examples of mistakes that had snuck past the careful scholars for decades, or of other zombies that refused to stay dead.

September 6, 2023

“[T]he preemptive hype about [Bottoms] has been fundamentally false, fundamentally dishonest about what constitutes artistic risk and personal risk in 2023″

Freddie deBoer — whose new book just got published — considers the way a new movie is being marketed, as if anything to do with LGBT issues is somehow still “daring” or “risky” or “challenging” to American audiences in the 2020s:

Consider this New York magazine cover story on the new film Bottoms, about a couple of lesbian teenagers (played by 28-year-olds) who start a high school fight club in order to try and get laid. I’m interested in the movie; it looks funny and I’ll watch it with an open mind. Movies that are both within and critiques of the high school movie genre tend to be favorites of mine. But the preemptive hype about it — which of course the creators can’t directly control — has been fundamentally false, fundamentally dishonest about what constitutes artistic risk and personal risk in 2023. The underlying premise of the advance discussion has been that making a high school movie about a lesbian fight club, today, is inherently subversive and very risky. And the thing is … that’s not true. At all. In fact, when I first read the premise of Bottoms I marveled at how perfectly it flatters the interests and worldview of the kind of people who write about movies professionally. As New York‘s Rachel Handler says,

[Bottoms has] had the lesbian Letterboxd crowd, which treats every trailer and teaser release like Gay Christmas, hot and bothered for months. After attending its hit SXSW premiere, comedian Jaboukie Young-White tweeted, “There will be a full reset when this drops.”

And yet to read reviews and thinkpieces and social media, you’d think that Bottoms was emerging into a culture industry where the Moral Majority runs the show. One of the totally bizarre things about contemporary pop culture coverage is that the “lesbian Letterboxd crowd” and subcultures like them — proud and open and loud champions of “diversity” in the HR sense — are prevalent, influential, and powerful, and yet we are constantly to pretend that they don’t exist. To think of Bottoms as inherently subversive, you have to pretend that the cohort that Handler refers to here has no voice, even as its voice is loud enough to influence a New York magazine cover story. This basic dynamic really hasn’t changed in the culture business in a decade, and that’s because the people who make up the profession prefer to think of their artistic and political tastes as permanently marginal even as they write our collective culture.

Essentially the entire world of for-pay movie criticism and news is made up of the kind of people who will stand up and applaud for a movie with that premise regardless of how good the actual movie is. And I suspect that Rachel Handler, the author of that piece, and its editors at New York, and the PR people for the film, and the women who made it, and most of the piece’s readers know that it isn’t brave to release that movie, in this culture, now. And as far as the creators go, that’s all fine; their job isn’t to be brave, it’s to make a good movie! They aren’t obligated to fulfill the expectation that movies and shows about LGBTQ characters are permanently subversive. But the inability of our culture industry to drop that narrative demonstrates the bizarre progressive resistance to recognizing that things change and that liberals in fact control a huge amount of cultural territory.

And here’s the thing: almost everybody in this industry, in media, would understand that narrative to be false, were I to put the case to them this way. This obviously isn’t remotely a big deal — in fact I’ve chosen this piece and topic precisely because it’s not a big deal — and I’m sure most people haven’t thought about it at all. (Why would they?) Still, if I could peel people in professional media off from the pack and lay this case out to them personally, I’m quite certain many of them would agree that this kind of movie is actually guaranteed a great deal of media enthusiasm because of its “representation”, and thus is in fact a very safe movie to release in today’s Hollywood — but they would admit it privately. Because “Anything involving LQBTQ characters or themes is still something that’s inherently risky and daring in the world of entertainment and media, in the year of our lord 2023” is both transparently horseshit and yet socially mandated, in industries in which most people are just trying to hold on and don’t need the hassle.

August 31, 2023

The sciences have replication problems … historians face similar issues

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes considers the history profession’s closest equivalent to the ongoing replication crisis in the sciences:

… I’ve become increasingly worried that science’s replication crises might pale in comparison to what happens all the time in history, which is not just a replication crisis but a reproducibility crisis. Replication is when you can repeat an experiment with new data or new materials and get the same result. Reproducibility is when you use exactly the same evidence as another person and still get the same result — so it has a much, much lower bar for success, which is what makes the lack of it in history all the more worrying.

Historical myths, often based on mere misunderstanding, but occasionally on bias or fraud, spread like wildfire. People just love to share unusual and interesting facts, and history is replete with things that are both unusual and true. So much that is surprising or shocking has happened, that it can take only years or decades of familiarity with a particular niche of history in order to smell a rat. Not only do myths spread rapidly, but they survive — far longer, I suspect, than in scientific fields.

Take the oft-repeated idea that more troops were sent to quash the Luddites in 1812 than to fight Napoleon in the Peninsular War in 1808. Utter nonsense, as I set out in 2017, though it has been cited again and again and again as fact ever since Eric Hobsbawm first misled everyone back in 1964. Before me, only a handful of niche military history experts seem to have noticed and were largely ignored. Despite being busted, it continues to spread. Terry Deary (of Horrible Histories fame), to give just one of many recent examples, repeated the myth in a 2020 book. Historical myths are especially zombie-like. Even when disproven, they just. won’t. die.

[…]

I don’t think this is just me being grumpy and pedantic. I come across examples of mistakes being made and then spreading almost daily. It is utterly pervasive. Last week when chatting to my friend Saloni Dattani, who has lately been writing a piece on the story of the malaria vaccine, I shared my

mounting paranoiahealthy scepticism of secondary sources and suggested she check up on a few of the references she’d cited just to see. A few days later and Saloni was horrified. When she actually looked closely, many of the neat little anecdotes she’d cited in her draft — like Louis Pasteur viewing some samples under a microscope and having his mind changed on the nature of malaria — turned out to have no actual underlying primary source from the time. It may as well have been fiction. And there was inaccuracy after inaccuracy, often inexplicable: one history of the World Health Organisation’s malaria eradication programme said it had been planned to take 5-7 years, but the sources actually said 10-15; a graph showed cholera pandemics as having killed a million people, with no citation, while the main sources on the topic actually suggest that in 1865-1947 it killed some 12 million people in British India alone.Now, it’s shockingly easy to make these mistakes — something I still do embarrassingly often, despite being constantly worried about it. When you write a lot, you’re bound to make some errors. You have to pray they’re small ones and try to correct them as swiftly as you can. I’m extremely grateful to the handful of subject-matter experts who will go out of their way to point them out to me. But the sheer pervasiveness of errors also allows unintentionally biased narratives to get repeated and become embedded as certainty, and even perhaps gives cover to people who purposefully make stuff up.

If the lack of replication or reproducibility is a problem in science, in history nobody even thinks about it in such terms. I don’t think I’ve ever heard of anyone systematically looking at the same sources as another historian and seeing if they’d reach the same conclusions. Nor can I think of a history paper ever being retracted or corrected, as they can be in science. At the most, a history journal might host a back-and-forth debate — sometimes delightfully acerbic — for the closely interested to follow. In the 1960s you could find an agricultural historian saying of another that he was “of course entitled to express his views, however bizarre.” But many journals will no longer print those kinds of exchanges, they’re hardly easy for the uninitiated to follow, and there is often a strong incentive to shut up and play nice (unless they happen to be a peer-reviewer, in which case some will feel empowered by the cover of anonymity to be extraordinarily rude).

August 30, 2023

The endless search for the “Easy mode” in military conflict

CDR Salamander on the search for shortcuts to military excellence, despite literal millennia of evidence that there are no such shortcuts:

As the Russo-Ukrainian War reaches its 20th month, I hope everyone has been sufficiently sobered up to stand firmly against those promoting the “72-hour War” or spin an attractive story about some transformational secret sauce that provides an “easy button” for those tasked to do the very hard work of preparing a nation for war should, and if, it were to come.

See the Battle of Hostomel if you need a recent example of where buying this wishcasting can get you.

There is a reason we have continually railed against this Potomac Flotilla mindset for the better part of two decades here — it is the self-delusion of faculty lounge theories running up against the Gods of the Military Copybook Headings reality what we have thousands of years of experience to reference.

We are not smarter than previous generations. There is no secret weapon or war winning technology — or magic beans — that will allow us to skip past the hard work of a viable strategy backed up by a properly resourced industrial capacity to build, maintain, deploy, and sustain a fighting force on the other side of the Pacific for years if needed.

Not 24-hours. Not 72-hours. Think 72-weeks to 72-months and you have your mind right.

[…]

We do no one any good allowing free run towards the national security version of the prosperity gospel, a branch of the transformationalist cult, and their “name it and claim it” attitude towards solving hard problems.

From LCS to DDG-1000, to optimal manning, to six-sigma supply nightmares, to 100-hour workweeks, to 72-hour war CONOPS, to the “Deter by Punishment,” to “1,000 ship navy,” to the offset of this POM cycle, to counter-historical excuses for … again … not doing the hard work that takes so long to bear fruit that someone else will get credit for it.

Every time we have our top leaders — smart hard working professionals with the best intentions — step up to sound more like this guy — the worse we will all be.

It degrades them and endangers everyone.

We don’t need to sell the utility of small drones being used down to the lowest levels of responsibility — it is demonstrated every day.

What we do need sold is Congress’s need to fund a revitalization of our defense industrial capacity and a focus on the naval and aerospace forces that will do most of the fighting in any expected war west of the International Dateline.

Supported by swarms of drones of all shapes and sizes.

August 23, 2023

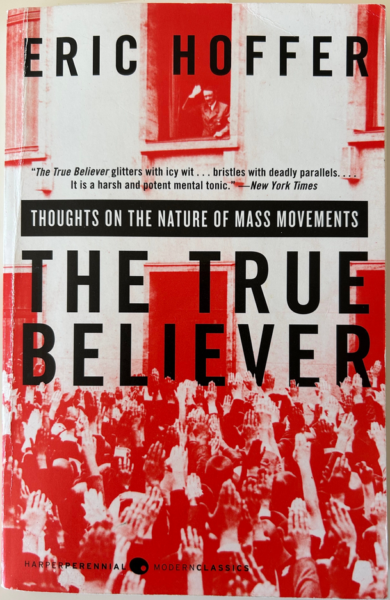

Frustration as a key driver in motivating mass unrest

Rob Henderson reviews the old classic The True Believer by Eric Hoffer:

Eric Hoffer made the case that if you peel back the layers of any mass movement, you will find that frustration is their driving force.

Frustration, though, doesn’t arise solely from bleak material conditions. The dockyard philosopher argued that “Our frustration is greater when we have much and want more than when we have nothing and want some. We are less dissatisfied when we lack many things than when we seem to lack but one thing.”

He points out in the years leading up to both the French and Russian Revolutions, life had in fact been gradually improving for the masses. He concludes, “It is not actual suffering but the taste of better things which excites people to revolt” and that “The intensity of discontent seems to be in inverse proportion to the distance from the object fervently desired.”

Personally, I saw this when I first arrived at Yale. I recall being stunned at how status anxiety pervaded elite college campuses. Internally, I thought, “You’ve already made it, what are you so stressed out about?” Hoffer, though, would say these students believed they had almost made it. That is why they were so aggravated. The closer they got to realizing their ambitions, the more frustrated they became about not already achieving them.

Hoffer’s conceptions of frustration highlight how if your conditions improve, but not as much or as quickly as you’d like, you will be vulnerable to recruitment by mass movements that promise to make your dreams come true.

In Democracy in America, Alexis de Tocqueville wrote, “When inequality is the general law of society, the most blatant inequalities escape notice. When everything is virtually on a level, the slightest variations cause distress. That is why the desire for equality becomes more insatiable as equality extends to all.” For Hoffer, this insatiability cultivates frustration — a nebulous, simmering emotional state that can be harnessed by any ideology.

He describes what has now become known as the “Tocqueville effect”: A revolution is most likely to occur after an improvement in social conditions. As circumstances improve, people raise their expectations. Societal reforms raise reference points to a level that is usually not matched, eliciting rage and frustration.

August 2, 2023

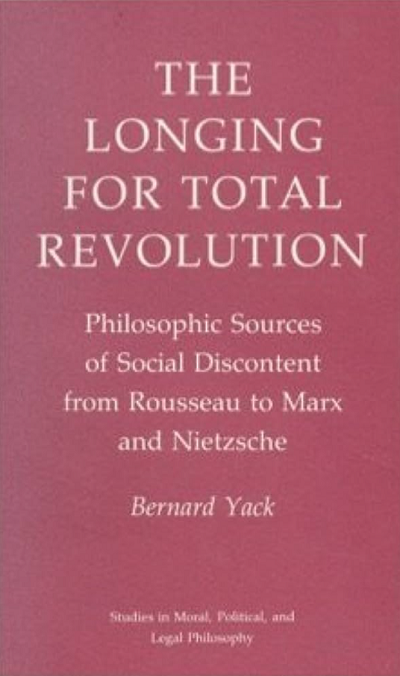

You say you want a revolution …

The latest book review from the Psmiths is Bernard Yack’s The Longing for Total Revolution: Philosophic Sources of Social Discontent from Rousseau to Marx and Nietzsche, by John Psmith:

This is a book by Bernard Yack. Who is Bernard Yack? Yack is fun, because for a mild-mannered liberal Canadian political theorist he’s dropped some dank truth-bombs over the years. For example, check out his short and punchy 2001 journal article “Popular Sovereignty and Nationalism” if you need a passive-aggressive gift for the democratic peace theorist in your life.1 The subject of that essay is unrelated to the subject of the book I’m reviewing, but the approach, the method, and the vibe are similar. The general Yack formula is to take some big trendy topic (like “nationalism”) and examine its deep philosophical and intellectual substructure while totally refusing to consider material conditions. He’s kind of like the anti-Marx — in Yack’s world not only do ideas have consequences, they’re about the only things that do. Even when this is unconvincing, it’s usually very interesting.

The topic of this book is radicalism in the ur-sense of “a desire to get to the root”. What Yack finds interesting about radicalism is that it’s so new. It’s a surprising fact that the entire idea of having a revolution, of burning down society and starting again with radically different institutions, was seemingly unthinkable until a certain point in history. It’s like nobody on planet Earth had the idea, and then suddenly sometime in the 17th or 18th century a switch flips and it’s all anybody is talking about. We’re used to that sort of pattern for scientific discoveries, or for very original ways of thinking about the universe, but “let’s destroy all of this and try again” isn’t an incredibly complex or sophisticated thought, so why did it take so many millennia for somebody to have it?

Well, first of all, is this claim even true? One thing you do see a lot of in premodern history is peasant rebellions, but dig a little deeper into any of them and the first thing you notice is that (sorry vulgar Marxists)2 there’s nothing especially “revolutionary” in any of these conflagrations. The most common cause of rebellion is some particular outrage, and the goal of the rebellion is generally the amelioration of that outrage, not the wholesale reordering of society as such. The next most common cause of rebellions is a bandit leader who is some variety of total psycho and gets really out of control. But again, prior to the dawn of the modern era, these psychos led movements that were remarkably undertheorized. The goal was sometimes for the psycho to become the new king, sometimes the extinguishment of all life on earth, but you hardly ever saw a manifesto demanding the end of kings as such. Again, this is weird, right? Is it really such a difficult conceptual leap to make?

Peasant rebellions are demotic movements, but modern revolutions are usually led by frustrated intellectuals and other surplus elites. When elites did get involved in pre-modern rebellions, their goals were still fairly narrow, like those of the peasants — sometimes they wanted to slightly weaken the power of the king, other times they wanted to replace the king with his cousin. But again this is just totally different in kind from the 18th century onwards, when intellectuals and nobles are spending practically all of their time sitting around in salons and cafés, debating whose plan for the total overhaul of society, morality, and economic relations is best.

The closest you get to this sort of thing is the tradition of Utopian literature, from Plato’s Republic to Thomas More, but what’s striking about this stuff is how much ironic distance it carried — nobody ever plotted terrorism to put Plato’s or More’s theories into practice. Nobody ever got really angry or excited about it. But skip forward to the radical theorizing of a Rousseau or a Marx or a Bakunin, and suddenly people are making plans to bomb schools because it might bring the Revolution five minutes closer. So what changed?

Well this is a Bernard Yack book, so the answer definitely isn’t the printing press. It also isn’t secularization, the Black Death, urbanization, the Reformation, the rise of industrial capitalism, the demographic transition, or any of the dozens of other massive material changes that various people have conjectured as the cause of radical political ferment. Instead Yack points to two abstract philosophical premises: the first is a belief in the possibility of “dehumanization”, the idea that one can be a human being and yet be living a less than human life. The second is “historicism” in the sense of a belief that different historical eras have fundamentally different modes of social interaction.

Both views had some historical precedent (for instance historicism is clearly evident in the writings of Machiavelli and Montesquieu), but it’s their combination that’s particularly explosive, and Rousseau is the first person to place the two elements together and thereby assemble a bomb. Because for Rousseau, unlike for any of the ancient or medieval philosophers, merely to be a member of the human species does not automatically mean you’re living a fully-human life. But if humanity is something you can grow into, then it’s also something that you can be prevented from growing into. Thus: “that I am not a better person becomes for Rousseau a grievance against the political order. Modern institutions have deformed me. They have made me the weak and miserable creature that I am.”

But what if the qualities of social interaction which have this dehumanizing effect are inextricably bound up with the dominant spirit of the age? In that case, it might be impossible to really live, impossible to produce happy and well-adjusted human beings, without a total overhaul of society and all of its institutions. This also clarifies how the longing for total revolution is distinct from utopianism — utopian literature is motivated by a vision of a better or more just order. Revolutionary longing springs from a hatred of existing institutions and what they’ve done to us. This is an important difference, because hate is a much more powerful motivator than hope. In fact Yack goes so far as to say (in a wonderfully dark passage) that the key action of philosophers and intellectuals upon history is the invention of new things to hate. Can you believe this guy is Canadian?

1. Of course, if my reading of MITI and the Japanese Miracle is correct, popular sovereignty may not be around for that much longer.

2. I say “vulgar” Marxists, because for the sophisticated Marxists (including Marx himself) it’s already pretty much dogma that premodern rebellions by immiserated peasants aren’t “revolutionary” in the way they care about.

July 30, 2023

“Give me Andrea Dworkin’s anti-fella fury over this matrician tripe any day of the week”

Brendan O’Neill clearly doesn’t think Caitlin Moran’s new book What About Men? is worth reading:

Men, I have bad news: Caitlin Moran is coming for us. She comes not to man-bash, not to holler: “All men are rapists!” It’s worse than that. She feels sorry for us. “I’m violently opposed to the branches of feminism that are permanently angry with men”, she writes at the very start of her very bad book. Instead she pities us. She frets over our toxic stoicism, our inability to be vulnerable, our unwillingness to be open about our fat bodies and small cocks. She wants to save us from all the “rules” about “what a man should be”. From all that “swagger” and “the stiff upper lip”. By the end I found myself pining for some good ol’ angry feminism. Give me Andrea Dworkin’s anti-fella fury over this matrician tripe any day of the week.

What About Men? is, I’m going to be blunt, rubbish. I knew it would be from the very first page where Moran says that “when it comes to the vag-based problems, I have the bantz”. Imagine using the word bantz unironically in 2023. What she means is that she’s done all the vagina stuff. She’s completed feminism. She’s known as “the Woman Woman”, she says, in an arrogant timbre that puts to shame those cocksure blokes who stalk her nightmares. She wrote the bestselling pop-feminist tome, How To Be a Woman (2011), which contained such gems of wisdom as “don’t shave your vagina” because it’s better to have a “big, hairy minge”, a “lovely furry moof”, “a marmoset sitting in [your] lap”, than a bald cooch. (Emmeline Pankhurst, I’m so sorry.) So now, naturally, she’s turning her attention to men. She’s discovered there is “a lot to say” about “men in the 21st-century”. Lucky us.

What she says about us is almost too daft for words. You realise by about page 22 that she’s never met a bloke from outside the media-luvvie, ageing rock-chick, “Glasto”-loving circle she famously inhabits. (I almost died of second-hand embarrassment when she said in How To Be a Woman that she lives an edgy existence, “like it’s 1969 all over again and my entire life is made of cheesecloth, sitars and hash”. Maam, you write a celebrity column for hundreds of thousands of pounds for The Times.)

Even her cultural references in What About Men? are off, as befits a woman who is essentially a square person’s idea of a cool person. She laments that young men are in “the grip of a fad” for super-skinny jeans. Jeans so tight they look “sprayed-on”. Jeans so tight that the poor lad’s balls end up “crushed against the crotch seam, in vivid detail”. Really? It’s not 2006. Bloc Party aren’t in the charts. I’m no follower of fashion but even I know most young men haven’t been wearing bollock-squashing jeans for a few years now. My nephews wear baggy jeans, à la Madchester. Pretty much the only time you see unyielding denim these days is on the portly thigh of a mid-life-crisis middle-class dad. The kind of men, dare I say it, that Ms Moran mixes with.

Her commentary on t-shirts is a dead giveaway, too. The only fashion flare the tragic male sex is allowed to enjoy is the tee, she says. Especially past the age of 40. You’ll see fortysomething fellas in “band t-shirts, slogan t-shirts, t-shirts with swearing on”, she says. Will you? Where? Again, only in the knowingly dishevelled privileged set Moran exists in. Every man in his forties I know always manages to put a shirt on. So desperate are emotionally repressed men to express themselves, says Moran, that some even buy t-shirts “from the back pages of Viz” that say things like “Breast Inspector” or “Fart Loading: Please Wait”. Not once in my life have I seen a man in a Viz tee. The problem here isn’t men – it’s Moran’s man-friends. She could have saved herself the trouble of this entire book by befriending some normal blokes.

That Moran’s pool of men is shallow is clear from the fact that all the men she talks to for the book seem to be as steeped as she is in chattering-class orthodoxy. She includes a transcript of long chats with male acquaintances and, honestly, reading it feels like being stuck in a lift with craft-beer wankers who do IT for the Guardian. At one point she informs her readers that her male friends are mostly “middle-aged, middle-class dads who know about wine, recycle, have views on thoughtful novels” and would probably “cry if they saw a dog struggling with a slight limp”. Writing a book about men from the perspective of men like that is like writing a book about women from the perspective of Princess Anne.

July 8, 2023

QotD: The amputation of the soul

Reading Mr Malcolm Muggeridge’s brilliant and depressing book, The Thirties, I thought of a rather cruel trick I once played on a wasp. He was sucking jam on my plate, and I cut him in half. He paid no attention, merely went on with his meal, while a tiny stream of jam trickled out of his severed œsophagus. Only when he tried to fly away did he grasp the dreadful thing that had happened to him. It is the same with modern man. The thing that has been cut away is his soul, and there was a period — twenty years, perhaps — during which he did not notice it.

It was absolutely necessary that the soul should be cut away. Religious belief, in the form in which we had known it, had to be abandoned. By the nineteenth century it was already in essence a lie, a semi-conscious device for keeping the rich rich and the poor poor. The poor were to be contented with their poverty, because it would all be made up to them in the world beyound the grave, usually pictured as something mid-way between Kew Gardens and a jeweller’s shop. Ten thousand a year for me, two pounds a week for you, but we are all the children of God. And through the whole fabric of capitalist society there ran a similar lie, which it was absolutely necessary to rip out.

Consequently there was a long period during which nearly every thinking man was in some sense a rebel, and usually a quite irresponsible rebel. Literature was largely the literature of revolt or of disintegration. Gibbon, Voltaire, Rousseau, Shelley, Byron, Dickens, Stendhal, Samuel Butler, Ibsen, Zola, Flaubert, Shaw, Joyce — in one way or another they are all of them destroyers, wreckers, saboteurs. For two hundred years we had sawed and sawed and sawed at the branch we were sitting on. And in the end, much more suddenly than anyone had foreseen, our efforts were rewarded, and down we came. But unfortunately there had been a little mistake. The thing at the bottom was not a bed of roses after all, it was a cesspool full of barbed wire.

It is as though in the space of ten years we had slid back into the Stone Age. Human types supposedly extinct for centuries, the dancing dervish, the robber chieftain, the Grand Inquisitor, have suddenly reappeared, not as inmates of lunatic asylums, but as the masters of the world. Mechanization and a collective economy seemingly aren’t enough. By themselves they lead merely to the nightmare we are now enduring: endless war and endless underfeeding for the sake of war, slave populations toiling behind barbed wire, women dragged shrieking to the block, cork-lined cellars where the executioner blows your brains out from behind. So it appears that amputation of the soul isn’t just a simple surgical job, like having your appendix out. The wound has a tendency to go septic.

The gist of Mr Muggeridge’s book is contained in two texts from Ecclesiastes: “Vanity of vanities, saith the preacher; all is vanity” and “Fear God, and keep His comandments: for this is the whole duty of man”. It is a viewpoint that has gained a lot of ground lately, among people who would have laughed at it only a few years ago. We are living in a nightmare precisely because we have tried to set up an earthly paradise. We have believed in “progress”. Trusted to human leadership, rendered unto Caesar the things that are God’s — that approximately is the line of thought.

Unfortunately Mr Muggeridge shows no sign of believing in God himself. Or at least he seems to take it for granted that this belief is vanishing from the human mind. There is not much doubt that he is right there, and if one assumes that no sanction can ever be effective except the supernatural one, it is clear what follows. There is no wisdom except in the fear of God; but nobody fears God; there fore there is no wisdom. Man’s history reduces itself to the rise and fall of material civilizations, one Tower of Babal after another. In that case we can be pretty certain what is ahead of us. Wars and yet more wars, revolutions and counter-revolutions, Hitlers and super-Hitlers — and so downwards into abysses which are horrible to contemplate, though I rather suspect Mr Muggeridge of enjoying the prospect.

George Orwell, “Notes on the Way”, Time and Tide, 1940-03-30.

June 28, 2023

“I’ll forgive Dartnell for not writing ‘Lest Darkness Fall’ For Dummies“

Jane Psmith reviews The Knowledge by Lewis Dartnell, despite it not being quite what she was hoping it would be:

This is not the book I wanted to read.

The book I wanted to read was a detailed guide to bootstrapping your way to industrial civilization (or at least antibiotics) if you should happen to be dumped back in, say, the late Bronze Age.1 After all, there are plenty of technologies that didn’t make it big for centuries or millennia after their material preconditions were met, and with our 20/20 hindsight we could skip a lot of the dead ends that accompanied real-world technological progress.

Off the top of my head, for example, there’s no reason you couldn’t do double-entry bookkeeping with Arabic numerals as soon as you have something to write on, and it would probably have been useful at any point in history — just not useful enough that anyone got really motivated to invent it. Or, here, another one: the wheelbarrow is just two simple machines stuck together, is substantially more efficient than carrying things yourself, and yet somehow didn’t make it to Europe until the twelfth or thirteenth century AD. Or switching to women’s work, I’ve always taken comfort in the fact that with my arcane knowledge of purling I could revolutionize any medieval market.2 And while the full Green Revolution package depends on tremendous quantities of fertilizer to fuel the grains’ high yields, you could get some way along that path with just knowledge of plant genetics, painstaking record-keeping, and a lot of hand pollination. In fact, with a couple latifundia at your disposal in 100 BC, you could probably do it faster than Norman Borlaug did. But speaking of fertilizer, the Italian peninsula is full of niter deposits, and while your revolutio viridis is running through those you could be figuring out whether it’s faster to spin up a chemical industry to the point you could do the Haber-Bosch process at scale or to get to the Peruvian guano islands. (After about thirty seconds of consideration my money’s on Peru, though it’s a shame we’re trying to do this with the Romans since they were never a notably nautical bunch and 100 BC was a low point even for them; you’ll have to wipe out the Mediterranean pirates early and find Greek or Egyptian shipwrights.) And another question: can you go straight from the Antikythera mechanism to the Jacquard machine, and if not what do you need in between? Inquiring minds want to know.3

But I’ll forgive Dartnell for not writing “Lest Darkness Fall” For Dummies, which I’ll admit is a pretty niche pitch, because The Knowledge is doing something almost as cool.4 Like my imaginary book, it employs a familiar fictional conceit to explain how practical things work. Instead of time travel, though, Dartnell takes as his premise the sudden disappearance (probably plague, definitely not zombies) of almost all of humanity, leaving behind a few survivors but all the incredible complexity of our technological civilization. How would you survive? And more importantly, how would you rebuild?

1. I read the Nantucket Trilogy at an impressionable age.

2. Knitting came to Europe in the thirteenth century, but the complementary purl stitch, which is necessary to create stretchy ribbing, didn’t. If you’ve ever wondered why medieval hosen were made of woven fabric and fit the leg relatively poorly, that’s why. When purling came to England, Elizabeth I paid an exorbitant amount of money for her first pair of silk stockings and refused to go back to cloth.

3. Obviously you would also need to motivate people to actually do any of these things, which is its own set of complications — Jason Crawford at Roots of Progress has a great review of Robert Allen’s classic The British Industrial Revolution in Global Perspective that gets much deeper into why no one actually cared about automation and mechanization — but please allow me to imagine here.

4. Please do not recommend How To Invent Everything, which purports to do something like this. It doesn’t go nearly deep enough to be interesting, let alone useful. You know, in the hypothetical that I’m sent back in time.

May 29, 2023

QotD: The size of the Great Library

… we can say that the Great Library was an extensive collection of books associated with the famous institute of learning and research that was the shrine of the Muses in Alexandria. That much is clear. But many of the other things often claimed about it are much less clear and some of them are pure fantasy, so it’s time to turn to the list of things that the “Great Library” was not.

“It was the largest library in the ancient world, containing over 700,000 books.”

It is entirely possible that it was the largest library in the ancient world, though we have no way of confirming this given that we have little reliable information about the size of its collection. Despite this, popular sources regularly repeat the huge figures given for the number of books in the library in several ancient sources, and usually opt for the ones that are the highest. Shakespeare scholar Stephen Greenblatt’s popular history The Swerve: How the Renaissance Began (Vintage, 2012) won critical acclaim and even garnered him a Pulitzer Prize, despite being panned by actual historians for its many howlers and weirdly old-fashioned historiography (see my detailed critical review here, with links to other scathing critiques by historians). Greenblatt’s account sticks closely to the nineteenth century narrative of “the dark ages” beloved by New Atheists, so it’s hardly surprising that the myths about the Great Library feature prominently in his account. Thus he informs his readers with great assurance that:

“At its height the Museum contained at least half a million papyrus rolls systematically organised, labelled and shelved according to a clever new system … alphabetical order.” (Greenblatt, p. 88)

The figure of “half a million scrolls” (or even “half a million books”) is the one that is usually bandied about, but even that colossal number is not quite enough for some polemicists. Attorney and columnist Jonathan Kirsch plumped for a much higher number in his book God Against the Gods: The History of the War Between Monotheism and Polytheism (Viking, 2004)

“In 390 AD … a mob of Christian zealots attacked the ancient library of Alexandria, a place where the works of the greatest rarity and antiquity had been collected … some 700,000 volumes and scrolls in all.” (Kirsch, p. 278)

Obviously the larger the collection in the Great Library the more terrible the tragedy of its loss, so those seeking to apportion blame for the supposed destruction of the Library usually go for these much higher numbers (it may be no surprise to learn that it’s the monotheists who are the “bad guys” in Kirsch’s cartoonish book). But did the Great Library really contain this huge number of books given that these numbers would represent a large library collection even today?

As with most things on this subject, it seems the answer is no. […] Some of these figures are interdependent, so for example Ammianus is probably depending, directly or indirectly, on Aulus Gellius for his “700,000” figure, which in turn is where Kirsch gets the same number in the quote above. Others look suspiciously precise, such as Epiphanius’ “54,800”. In summary of a lot of discussion by critical scholars, the best thing to say is that none of these figures is reliable. In her survey of the historiography of the issue, Diana Delia notes “lacking modern inventory systems, ancient librarians, even if they cared to, scarcely had the time or means to count their collections” (see Delia, “From Romance to Rhetoric: The Alexandrian Library in Classical and Islamic Traditions”, The American Historical Review, Vol. 97, No. 5, Dec. 1992, pp. 1449-67, p. 1459). Or as another historian once put it wryly “There are no statistics in ancient sources, just rhetorical flourishes made with numbers.”

One way that historians can make estimates of the size of ancient libraries is by examining the floor plans of their ruins and calculating the space their book niches would have taken up around the walls and then the number of scrolls each niche could hold. This works for some other ancient libraries for which we have surveyable remains, but unfortunately that is not the case for the Mouseion, given that archaeologists still have to guess where exactly it stood. So Columbia University’s Roger S. Bagnall has taken another tack. In a 2002 paper that debunks several of the myths about the Great Library (see Bagnall, “Alexandria: Library of Dreams”, Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 146, No. 4, Dec. 2002, pp. 348-362), he begins with how many authors we know were writing in the early Hellenistic period. He notes that we know of around 450 authors for whom we have, at the very least, some lines of writing whose work existed in the fourth century BC and another 175 from the third century BC. He points out that most of these writers probably only wrote works that filled a couple of scrolls at most, though a small number of them – like the playwrights – would have had a total corpus that filled many more than that, even up to 100 scrolls. So by adopting the almost certainly far too high figure of an average of 50 scrolls to contain the work of each writer, Bagnall arrives as a mere 31,250 scrolls to contain all the works of all the writers we know about to the end of the third century. He notes:

“We must then assume, to save the ancient figures for the contents of the Library, either that more than 90 percent of classical authors are not even quoted or cited in what survives, or that the Ptolemies acquired a dozen copies of everything, or some combination of these unlikely hypotheses. If we were (more plausibly) to use a lower average output per author, the hypotheses needed to save the numbers would become proportionally more outlandish.” (Bagnall, p. 353)

Bagnall makes other calculations taking into account guesses at what number of completely lost authors there may have been and still does not manage to get close to most of the figures given in our sources. His analysis makes it fairly clear that these numbers, presented so uncritically by popular authors for rhetorical effect, are probable fantasies. As mentioned above, when we can survey the archaeology of an ancient library’s ruins, some estimate can be made of its holdings. The library in the Forum of Trajan in Rome occupied a large space 27 by 20 metres and Lionel Casson estimates it could have held “in the neighbourhood of 20,000 scrolls” (Casson, p. 88). A similar survey of the remains of the Great Library of Pergamon comes to an estimate of 30,000 scrolls there. Given that this library was considered a genuine rival to the Great Library of Alexandria, it is most likely that the latter held around 40-50,000 scrolls at its height, containing a smaller number of works overall given that ancient works usually took up more than one scroll. This still seems to have made it the largest library collection in the ancient world and thus the source of its renown and later myths, but it’s a far cry from the “500,000” or “700,000” claimed by uncritical popular sources and people with axes to grind.

Tim O’Neill, “The Great Myths 5: The Destruction Of The Great Library Of Alexandria”, History for Atheists, 2017-07-02.

April 26, 2023

HMS Prince of Wales, the media’s favourite target of abuse

Sir Humphrey defends the Royal Navy’s handling of the unplanned repairs to HMS Prince of Wales against the British media’s constant clamour that the ship is somehow cursed and not as good as sister ship HMS Queen Elizabeth by any measure:

It’s never easy being the younger child. You don’t get anywhere near the same level of interest when key development milestones occur, people take your presence far more for granted and you often end up with your older sibling’s “hand me downs” and cast-offs. This is definitely true for warships where there is sometimes a perception that the first of class has a style and elan that other siblings lack. In the case of the QUEEN ELIZABETH class aircraft carriers it could be argued that QE has very much grabbed the headlines and glory while the PRINCE OF WALES (PWLS) has perhaps lacked as exciting an opportunity.

Following an incident which involved a propellor loss (something that befalls other navies too as the French carrier CHARLES DE GAULLE discovered), PWLS has had a challenging year in dry dock. The media are reporting it as the ship is broken, she needs a year in dock for extensive repairs and now todays Mail on Sunday story is that she has effectively become a “scrapyard” for her older sibling, providing parts and materiel as a donor vessel. It has hard to think of a less loved vessel in the eyes of the media. What is actually going on is a little more complex and perhaps boring.

In reality PWLS was sent to Scotland for an unplanned dry docking to resolve the issues with her propellor shaft. It seems to have become clear that this would take some months to resolve – which can feel a long time in a 24/7 newscycle, but realistically feels about right for repairing an extremely complex major warship and in line with historical timescales. The original plan for PWLS was that after she came back from the US last year, she’d not deploy in 2024 before undergoing a major capability upgrade anyway during the year. The purpose of this upgrade, which is standard for all newbuild warships, is to add on the new equipment and capabilities that have entered service since her build design was frozen many years ago.

Part of the challenge of building a complex warship is that at some point you need to lock the design down to enable construction to begin, rather than tinkering it to handle every new “oooh shiny” moment as new technology emerges. To solve this ships will usually enter service as per the specs agreed years before, then a period in refit is planned early in her life once the ship is working and commissioned to add on the various equipment items that have entered use. This is about bringing the ship up to the most modern standard at the time – throughout her life she will then continue to receive regular upgrades like this as new technology is developed.

In this case the plan evolved so that as she was in dry dock anyway the RN seems to have decided to merge the two pieces of work. What this means is that rather than return to sea in a meaningful way, PWLS will have spent about a year in both unplanned repairs and planned refit. Again this period of time out of service isn’t unusual for a major warship – if you look through most vessels lifespans, refits of 1-3 years are entirely common. It can though appear bad news if you interpret this data as saying that the emergency repairs will take a year.

April 25, 2023

QotD: What is military history?

The popular conception of military history – indeed, the conception sometimes shared even by other historians – is that it is fundamentally a field about charting the course of armies, describing “great battles” and praising the “strategic genius” of this or that “great general”. One of the more obvious examples of this assumption – and the contempt it brings – comes out of the popular CrashCourse Youtube series. When asked by their audience to cover military history related to their coverage of the American Civil War, the response was this video listing battles and reflecting on the pointless of the exercise, as if a list of battles was all that military history was (the same series would later say that military historians don’t talk about about food, a truly baffling statement given the important of logistics studies to the field; certainly in my own subfield, military historians tend to talk about food more than any other kind of historian except for dedicated food historians).

The term for works of history in this narrow mold – all battles, campaigns and generals – is “drums and trumpets” history, a term generally used derisively. The study of battles and campaigns emerged initially as a form of training for literate aristocrats preparing to be officers and generals; it is little surprise that they focused on aristocratic leadership as the primary cause for success or failure. Consequently, the old “drums and trumpets” histories also had a tendency to glory in war and to glorify commanders for their “genius” although this was by no means universal and works of history on conflict as far back as Thucydides and Herodotus (which is to say, as far back as there have been any) have reflected on the destructiveness and tragedy of war. But military history, like any field, matured over time; I should note that it is hardly the only field of history to have less respectable roots in its quite recent past. Nevertheless, as the field matured and moved beyond military aristocrats working to emulate older, more successful military aristocrats into a field of scholarly inquiry (still often motivated by the very real concern that officers and political leaders be prepared to lead in the event of conflict) the field has become far more sophisticated and its gaze has broadened to include not merely non-aristocratic soldiers, but non-soldiers more generally.

Instead of the “great generals” orientation of “drums and trumpets”, the field has moved in the direction of three major analytical lenses, laid out quite ably by Jeremy Black in “Military Organisations and Military Charge in Historical Perspective” (JMH, 1998). He sets out the three basic lenses as technological, social and organizational, which speak to both the questions being asked of the historical evidence but also the answers that are likely to be provided. I should note that these lenses are mostly (though not entirely) about academic military history; much of the amateur work that is done is still very much “drums and trumpets” (as is the occasional deeply frustrating book from some older historians we need not discuss here), although that is of course not to say that there isn’t good military history being written by amateurs or that all good military history narrowly follows these schools. This is a classification system, not a straight-jacket and I am giving it here because it is a useful way to present the complexity and sophistication of the field as it is, rather than how it is imagined by those who do not engage with it.

[…]

The technological approach is perhaps the least in fashion these days, but Geoffery Parker’s The Military Revolution (2nd ed., 1996) provides an almost pure example of the lens. This approach tends to see changing technology – not merely military technologies, but often also civilian technologies – as the main motivator of military change (and also success or failure for states caught in conflict against a technological gradient). Consequently, historians with this focus are often asking questions about how technologies developed, why they developed in certain places, and what their impacts were. Another good example of the field, for instance, is the debate about the impact of rifled muskets in the American Civil War. While there has been a real drift away from seeing technologies themselves as decisive on their own (and thus a drift away from mostly “pure” technological military history) in recent decades, this sort of history is very often paired with the others, looking at the ways that social structures, organizational structures and technologies interact.

Perhaps the most popular lens for military historians these days is the social one, which used to go by the “new military history” (decades ago – it was the standard form even back in the 1990s) but by this point comprises probably the bulk of academic work on military history. In its narrow sense, the social perspective of military history seeks to understand the army (or navy or other service branch) as an extension of the society that created it. We have, you may note, done a bit of that here. Rather than understanding the army as a pure instrument of a general’s “genius” it imagines it as a socially embedded institution – which is fancy historian speech for an institution that, because it crops up out of a society, cannot help but share that society’s structures, values and assumptions.

The broader version of this lens often now goes under the moniker “war and society”. While the narrow version of social military history might be very focused on how the structure of a society influences the performance of the militaries that created it, the “war and society” lens turns that focus into a two-way street, looking at both how societies shape armies, but also how armies shape societies. This is both the lens where you will find inspection of the impacts of conflict on the civilian population (for instance, the study of trauma among survivors of conflict or genocide, something we got just a bit with our brief touch on child soldiers) and also the way that military institutions shape civilian life at peace. This is the super-category for discussing, for instance, how conflict plays a role in state formation, or how highly militarized societies (like Rome, for instance) are reshaped by the fact of processing entire generations through their military. The “war and society” lens is almost infinitely broad (something occasionally complained about), but that broadness can be very useful to chart the ways that conflict’s impacts ripple out through a society.

Finally, the youngest of Black’s categories is organizational military history. If social military history (especially of the war and society kind) understands a military as deeply embedded in a broader society, organizational military history generally seeks to interrogate that military as a society to itself, with its own hierarchy, organizational structures and values. Often this is framed in terms of discussions of “organizational culture” (sometimes in the military context rendered as “strategic culture”) or “doctrine” as ways of getting at the patterns of thought and human interaction which typify and shape a given military. Isabel Hull’s Absolute Destruction: Military Culture and the Practices of War in Imperial Germany (2006) is a good example of this kind of military history.

Of course these three lenses are by no means mutually exclusive. These days they are very often used in conjunction with each other (last week’s recommendation, Parshall and Tully’s Shattered Sword (2007) is actually an excellent example of these three approaches being wielded together, as the argument finds technological explanations – at certain points, the options available to commanders in the battle were simply constrained by their available technology and equipment – and social explanations – certain cultural patterns particular to 1940s Japan made, for instance, communication of important information difficult – and organizational explanations – most notably flawed doctrine – to explain the battle).

Inside of these lenses, you will see historians using all of the tools and methodological frameworks common in history: you’ll see microhistories (for instance, someone tracing the experience of a single small unit through a larger conflict) or macrohistories (e.g. Azar Gat, War in Human Civilization (2008)), gender history (especially since what a society views as a “good soldier” is often deeply wrapped up in how it views gender), intellectual history, environmental history (Chase Firearms (2010) does a fair bit of this from the environment’s-effect-on-warfare direction), economic history (uh … almost everything I do?) and so on.

In short, these days the field of military history, as practiced by academic military historians, contains just as much sophistication in approach as history more broadly. And it benefits by also being adjacent to or in conversation with entire other fields: military historians will tend (depending on the period they work in) to interact a lot with anthropologists, archaeologists, and political scientists. We also tend to interact a lot with what we might term the “military science” literature of strategic thinking, leadership and policy-making, often in the form of critical observers (there is often, for instance, a bit of predictable tension between political scientists and historians, especially military historians, as the former want to make large data-driven claims that can serve as the basis of policy and the later raise objections to those claims; this is, I think, on the whole a beneficial interaction for everyone involved, even if I have obviously picked my side of it).

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Why Military History?”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2020-11-13.

April 23, 2023

There’s a spectre haunting your pantry – the spectre of “Ultra-Processed Food”

Christopher Snowden responds to some of the claims in Chris van Tulleken’s book Ultra-Processed People: Why Do We All Eat Stuff That Isn’t Food … And Why Can’t We Stop?:

Ultra-processed food (UPF) is the latest bogeyman in diet quackery. The concept was devised a few years ago by the Brazilian academic Carlos Monteiro who also happens to be in favour of draconian and wildly impractical regulation of the food supply. What are the chances?!

Laura Thomas has written some good stuff about UPF. The tldr version is that, aside from raw fruit and veg, the vast majority of what we eat is “processed”. That’s what cooking is all about. Ultra-processed food involves flavourings, sweeteners, emulsifiers etc. that you wouldn’t generally use at home, often combined with cooking processes such as hydrogenation and hydrolysation that are unavailable in an ordinary kitchen. In short, most packaged food sold in shops is UPF.

Does this mean a cake you bake at home (“processed”) is less fattening than a cake you buy from Waitrose (“ultra-processed”)? Probably not, so what is the point of the distinction? This is where the idea breaks down. All the additives used by the food industry are considered safe by regulators. Just because the layman doesn’t know what a certain emulsifier is doesn’t mean it’s bad for you. There is no scientific basis for classifying a vast range of products as unhealthy just because they are made in factories. Indeed, it is positively anti-scientific insofar as it represents an irrational fear of modernity while placing excessive faith in what is considered “natural”. There is also an obvious layer of snobbery to the whole thing.

Taken to an absurd but logical conclusion, you could view wholemeal bread as unhealthy so long as it is made in a factory. When I saw that CVT has a book coming out (of course he does) I was struck by the cover. Surely, I thought, he was not going to have a go at brown bread?

But that is exactly what he does.

During my month-long UPF diet, I began to notice this softness most starkly with bread — the majority of which is ultra-processed. (Real bread, from craft bakeries, makes up just 5 per cent of the market …

His definition of “real bread” is quite revealing, is it not?

For years, I’ve bought Hovis Multigrain Seed Sensations. Here are some of its numerous ingredients: salt, granulated sugar, preservative: E282 calcium propionate, emulsifier: E472e (mono- and diacetyltartaric acid esters of mono- and diglycerides of fatty acids), caramelised sugar, ascorbic acid.

Let’s leave aside the question of why he only recently noticed the softness of fake bread if he’s been eating it for years. Instead, let’s look at the ingredients. Like you, I am not familiar with them all, but a quick search shows that E282 calcium propionate is a “naturally occurring organic salt formed by a reaction between calcium hydroxide and propionic acid”. It is a preservative.

E472e is an emulsifier which interacts with the hydrophobic parts of gluten, helping its proteins unfold. It adds texture to the bread.

Ascorbic acid is better known as Vitamin C.

Caramelised sugar is just sugar that’s been heated up and is used sparingly in bread; Jamie Oliver puts more sugar in his homemade bread than Hovis does.

Hovis Multigrain Seed Sensations therefore qualifies as UPF but it is far from obvious why it should be regarded as unhealthy. According to CVT, the problem is that it is too easy to eat.

The various processes and treatment agents in my Hovis loaf mean I can eat a slice even more quickly, gram for gram, than I can put away a UPF burger. The bread disintegrates into a bolus of slime that’s easily manipulated down the throat.

Does it?? I’ve never tried this brand but it doesn’t ring true to me. It’s just bread. Either you toast it or you use it for sandwiches. Are there people out there stuffing slice after slice of bread down their throats because it’s so soft?

By contrast, a slice of Dusty Knuckle Potato Sourdough (£5.99) takes well over a minute to eat, and my jaw gets tired.

Far be it from me to tell anyone how to spend their money but, in my opinion, anyone who spends £6 on a loaf of bread is an idiot. Based on his description, the Dusty Knuckle Potato Sourdough is awful anyway. Is that the idea? Is the plan to make eating so jaw-achingly unenjoyable that we do it less? Is the real objection to UPF simply that it tastes nice?