If you don’t know much about Le Corbusier, for instance, Scott’s book [Seeing Like A State] will reveal to you that he was as banally evil in his way as Adolf Eichmann, and for the same reason: to him, humans were just cells on spreadsheets. They need so many square feet in which to sleep, shit, and eat, and so the only principle of architecture should be, what’s the most efficient way to get them their bare minimums? “Machines for living”, he called his apartment buildings, and may God have mercy on his shriveled little soul, he meant it. Image search “Chandigarh, India” to see where this leads — an entire city designed for machinelike “living”, totally devoid of anything human.

But most bureaucrats aren’t evil, just ignorant … and as Scott shows, this ignorance isn’t really their fault. They don’t know what they don’t know, because they can’t know. Very few bureaucratic cock-ups are as blatant as Chandigarh, where all anyone has to do is look at pictures for five minutes to conclude “you couldn’t pay me enough to move there”.

Severian, “The Finger is Not the Moon”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2021-09-14.

November 25, 2024

QotD: Le Corbusier

August 28, 2024

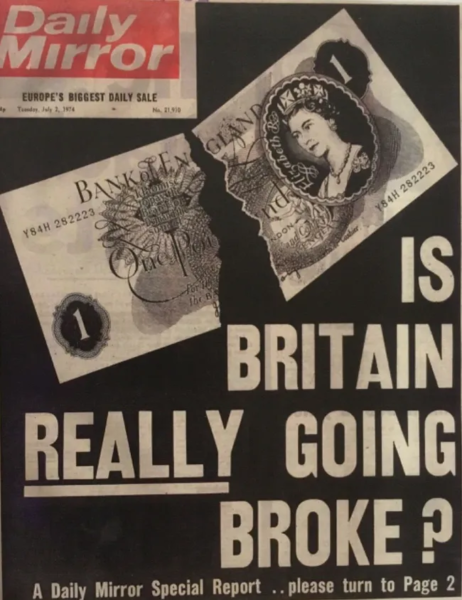

1974 – Britain’s nadir

In the second part of Ed West‘s appreciation of Dominic Sandbrook’s Seasons in the Sun, Britain was described as “sliding, sinking, shabby, dirty, lazy, inefficient, dangerous, in its death throes, worn out, clapped out, occasionally lashing out” by Margaret Drabble in her 1977 novel The Ice Age, and it certainly seems to fit the bill quite well:

The Times reported in October of that year that London’s West End was in a “sorry state”, with parts of Shaftesbury Avenue and Charing Cross Road “in the sort of condition that, in Birmingham or Manchester, would qualify them for wholesale slum clearance”.

Journalist Clive Irving wrote that London had become “a semi-derelict slum”, a city blighted by “tacky porno shops, skin movies, pinball arcades, and toxic hamburger joints” while “behind neon facades the buildings are flaking and unkempt”.

The capital had lost a million and a half people since its peak in 1939, and would continue its decline for another decade. Whitehall Mandarin Ronald McIntosh declared that “London is evidently losing population quite heavily [and] services are steadily deteriorating, and nobody seems to have the least idea of how to deal with it”.

The country as a whole was haemorrhaging people, and in 1975 its population fell for the first time since records began. In the spring of 1974 applications for emigration to Canada went up 65 per cent, while New Zealand even felt compelled to put restrictions on people fleeing the old country.

Doctors in particular were leaving in droves, and recruitment agency Robert Lee International estimated that the number of professionals wanting to move abroad rose by 35% in just six months, from January and July 1975. Interest was keenest among engineers, accountants, scientists and teachers.

Many high earners were fleeing excessive tax rates, so punitive that even the Bond producer Albert R Broccoli left to make the iconic British movies elsewhere, and Moonraker would be filmed in France.

Gone were the days of the Swinging Sixties; instead, the London of George Smiley was “the city of the Sex Pistols and The Sweeney, not the Beatles and The Avengers; a city of tramps and hooligans, hustlers and muggers, the downtrodden and the disappointed, haunted by the deadly figure of the IRA bomber”.

Britain’s second city was in an even worse state. During Wilson’s first term Birmingham had been hailed as “the most go-ahead city in Europe”. Now the Times admitted it looked like a “large and chaotic building site”.

Travel writer Jonathan Raban described Southampton’s Millbrook estate as “a vast, cheap storage unit for nearly 20,000 people”. The country’s increasing problem with crime, hooliganism, graffiti and drug addiction meant that residents wouldn’t even hang their clothes in communal areas, for fear of theft.

The great architectural feats of the post-war era were beginning to look like a miserable failure, and none more so than the utopian social housing schemes, which had often entailed destroying closely-knit and organic communities in overcrowded and run-down – but rescuable – terraced housing.

Christopher Brooker visited Keeling House in Bethnal Green and found “its concrete cracked and discolouring, the metal reinforcement rusting through the surface, every available inch covered with graffiti”. Here was the story of modern Britain, “the bright, anticipated dream followed by a seedy, nightmarish reality”.

The National Theatre’s Peter Hall visited the New York Juilliard School and upon return home “found it depressing to compare it with our own already run-down, ill-maintained South Bank building”.

“The English apparently no longer care enough about material surroundings,” he wrote: “They even seem to take a positive pleasure in defiling them.”

August 26, 2024

History Summarized: Beauty and Brutalism

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published May 10, 2024No no no guys you just don’t GET IT, Brutalism is actually really clever and impressive and in this essay I wi–

SOURCES & Further Reading:

Architecture in Minutes: 200 key buildings and movements in an instant by Susie Hodge – an extremely useful reference for 20th century structures and famous figures outside my usual wheelhouse, and the fortuitous inspiration for this video via the entry on “Concrete” with an opposite-facing image of the Baha’i House of Worship

“Brutalism was the Greatest Architectural Movement in History. Change My Mind.” by Pat Finn, Architizer, https://architizer.com/blog/inspirati…

“Concrete: the most destructive material on Earth” by Jonathan Watts, The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/cities/20…

“The Salk Institute and the Lost Ethics of Brutalism” by James E Churchill, Docomomo, https://www.docomomo-us.org/news/the-…

“The New Brutalism” by Reyner Banham, Architectural Review, https://www.architectural-review.com/…

“Busting the Myths of Brutalism” by Stewart Hicks @stewarthicks, My Take on the Whole Brutalism ThingMusic:

“Scheming Weasel” by Kevin MacLeod (Incompetech.com)

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/… Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 4.0 LicenseOur content is intended for teenage audiences and up.

PODCAST: https://overlysarcasticpodcast.transi…

MERCH: https://overlysarcastic.shop/

OUR WEBSITE: https://www.OverlySarcasticProductions.com

September 26, 2023

Postwar Warsaw became beautiful, but postwar Coventry became a modernist eyesore

Ed West’s Wrong Side of History remembers how the devastation of Warsaw during World War 2 was replaced by as true a copy as the Poles could manage, while Coventry — a by-word for urban destruction in Britain — became a plaything in the hands of urban planners:

Stare Miasto w Warszawie po wojnie (Old Town in Warsaw after the war)

Polish Press Agency via Wikimedia Commons.

Fifteen months after its Jewish ghetto rose up in a last ditch attempt to avoid annihilation, the people of the city carried out one final act of defiance against Nazi occupation in August 1944.

The Soviets, having helped to start the war in 1939 with the fourth partition of Poland, deliberately halted their advance and refused to help the city in its torment. Without Russian cooperation, the western allies could do little more than an airlift of weapons and supplies, which was doomed to failure.

The Polish Army and resistance fought bravely – some 20,000 Germans were killed or wounded – but at huge cost. As many as 200,000 Poles, most civilians, were killed in the battle and over 80% of the city destroyed – worse destruction than Hiroshima or Nagasaki. And so the Nazis had carried out their plan to erase the Polish capital — yet this was something the Poles refused to accept, even after 1944

Today the Old Town is as beautiful as it ever was, and visitors from around the world come to walk its streets – witnesses to perhaps the most remarkable ever story of urban rebirth.

With the city a pile of rubble and corpses, the post-war communist authorities considered moving the capital elsewhere, and some suggested that the remains of Warsaw be left as a memorial to war, but the civic leaders insisted otherwise – the city would rise again

Warsaw was fought over, bombed, shelled, invaded and twice was the epicentre of brutal urban guerilla warfare, leaving the city in literal ruins. Coventry, on the other hand, wasn’t bombed by the Luftwaffe until 1940 — but the damage had already began at the hands of the urban planners:

Broadgate in Coventry city centre following the Coventry Blitz of 14/15 November 1940. The burnt out shell of the Owen Owen department store (which had only opened in 1937) overlooks a scene of devastation.

War Office photo via Wikimedia Commons.

The attack was devastating, to the local people and the national psyche, and local historian W.G. Hoskins wrote that “For English people, at least, the word Coventry has had a special sound ever since that night”. Yet Coventry also became a byword for how to not to rebuild a city – indeed the city authorities even saw the Blitz as an opportunity to remake the city in their own image.

Coventry forms a chapter in Gavin Stamp’s Britain’s Lost Cities, a remarkable – if depressing – coffee table book illustrating what was done to our urban centres. Stamp wrote:

British propaganda was quick to exploit this catastrophe to emphasise German ruthlessness and barbarism and to make Coventry into a symbol of British resilience. Photographs of the ruins of the ancient Cathedral were published around the world, and it was insisted that it would rise again, just as the city itself would be replanned and rebuilt, better than before.

But the story of the destruction of Coventry is not so simple or straightforward. … severe as the damage was, a large number of ancient buildings survived the war – only to be destroyed in the cause of replanning the city. But what is most shocking is that the finest streets of old Coventry, filled with picturesque half-timbered houses, had been swept away before the outbreak of war – destroyed not by the Luftwaffe but by the City Engineer. Even without the second world war, old Coventry would probably have been planned out of existence anyway.

In one respect, Coventry had been ready for the attacks … the vision of “Coventry of Tomorrow” was exhibited in May 1940 – before the bombing started. [City engineer] Gibson later recalled that “we used to watch from the roof to see which buildings were blazing and then dash downstairs to check how much easier it would be to put our plans into action”.

The Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings had estimated that 120 timber houses had survived the war … two thirds of these would disappear over the next few years as the city engineer pressed forward with his plans … A few buildings were retained, but removed from their original sites and moved to Spon Street as a sanitised and inauthentic historic quarter.

Today, whatever integrity the post-war building ever had has been undermined by subsequent undistinguished alterations and replacements. Coventry has been more transformed in the 20th century than any other city in Britain, both in terms of its buildings and street pattern. The three medieval spires may still stand, but otherwise the appearance of England’s Nuremberg can only be appreciated in old photographs.

In fact, the destruction had begun before the war. In order to make the city easier for drivers, the west side had been knocked down in the 1930s, the area around Chapel St and Fleet St replaced by Corporation St in 1929-1931. After the war it would become a shopping centre.

Old buildings by Holy Trinity Church were destroyed in 1936-7, and that same year Butcher Row and the Bull Ring were similarly pulled down, the Lord Mayor calling the former “a blot in the city”.

Indeed, the city architect Donald Gibson hailed the Blitz as “a blessing in disguise. The Jerries cleared out the core of the city, a chaotic mess, and now we can start anew.” He said later that “We used to watch from the roof to see which buildings were blazing and then dash downstairs to check how much easier it would be to put our plans into action”.

Gibson’s plan became city council policy in February 1941, with a new civic centre and a shopping precinct inside a ring road. The City Engineer Ernest Ford wanted to preserve some old buildings, including the timber Ford’s Hospital, which had survived the Blitz. Gibson said it was an “unnecessary problem” and in the way of a new straight road.

October 22, 2022

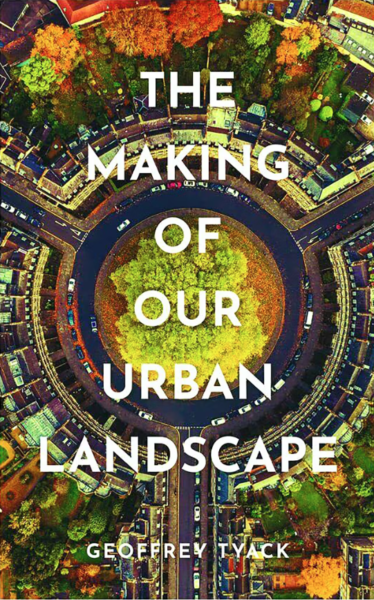

Two new works on British architecture through the years

In The Critic, James Stevens Curl discusses two recent books on the “monuments and monstrosities” of British architecture:

The most startling achievement of the Victorian period was Britain’s urbanisation. By the 1850s the numbers living in rural parts were fractionally down on those in urban areas. By the end of Victoria’s reign more than 75 per cent of the population were town-dwellers, and a romantic nostalgic longing for a lost rural paradise was fostered by those who denigrated urbanisation. This myth of a lost rural ideal led to phenomena such as garden cities and suburbia. Anti-urbanists and critics of the era detested the one thing that gave the Victorian city its great qualities: they were frightened of and hated the Sublime.

These two books deal with the urban landscape in different ways. Tyack provides a chronological narrative of the history of some British towns and cities spread over two millennia from Roman times to the present day, so his is a very ambitious work. Most towns of modern Britain already existed in some form by 1300, he rightly states, though a few were abandoned, such as Calleva Atrebatum (Silchester) in Hampshire, a haunted place of great and poignant beauty with impressive remains still visible. Most Roman towns were more successful, surviving and developing through the centuries, none more so than London. Tyack describes several in broad, perhaps too broad, terms.

He outlines the creation of dignified civic buildings from the 1830s onwards, reflecting the evolution of local government as power shifted to the growing professional, manufacturing and middle classes: fine town halls, art galleries, museums, libraries, concert halls, educational buildings and the like proliferated, many of supreme architectural importance. Yet the civic public realm has been under almost continuous attack from central government and the often corrupt forces of privatisation for the last half century.

Tyack is far too lenient when considering the unholy alliances between legalised theft masquerading as “comprehensive redevelopment”, local and national government, architects, planners and large construction firms with plentiful supplies of bulging brown envelopes. Perfectly decent buildings, which could have been rehabilitated and updated, were torn down, and whole communities were forcibly uprooted in what was the greatest assault in history on the urban fabric of Britain and the obliteration of the nation’s history and culture.

One of the worst professional crimes ever inflicted on humanity was the application of utopian modernism to the public housing-stock of Britain from the 1950s onwards: this dehumanised communities, spoiled landscapes and ruined lives, yet the architectural establishment remained in total denial. In 1968–72 the Hulme district of Manchester was flattened to make way for a modernist dystopia created by a team of devotees of Corbusianity.

The huge quarter-mile long six-storey deck-access “Crescents” were shabbily named after architects of the Georgian, Regency and early-Victorian periods (Adam, Barry, Kent and Nash). This monstrous, hubristic imposition rapidly became one of the most notoriously dysfunctional housing estates in Europe, a spectacular failure whose problems were all-too-apparent from the very beginning. Yet in The Buildings of England 1969, Manchester was praised for “doing more perhaps than any other city in England … in the field of council housing”. The “Crescents” were recognised quickly as unparalleled disasters and hated by the unfortunates forced to live there. They were demolished in the 1990s, but the creators of that hell were never punished.

December 28, 2021

“After the Second World War, the architecture-industrial complex … began a massive rebuilding of major cities”

In The Critic, Nikos A. Salingaros decries “architectural urbanicide”:

Cumbernauld Shopping Centre, voted as Britain’s most hated building.

Photo by Ed Webster via Wikimedia Commons.

Biological life transforms energy from the sun into complexes of organic materials that either metabolize while remaining relatively fixed, or move about and eat each other. Human energy creates the analogous case of artifacts and buildings, which give us a healing effect akin to the feedback experienced from our interaction with biological organisms. This positive emotion corresponds to the mechanism of “biophilia”.

Women grow and nurture the human baby. They are predisposed to appreciate the created life form through an intense bond of love through beauty. Most people — though not all, a notable exception being the architect Le Corbusier — love babies and have a built-in reflex of smiling at the sight of one, even if it’s not their own. Beauty is inseparable from creation and life.

Established architecture in our times, and for a century before now, has been an almost exclusively male domain, dominated by sheer power. The profession has aligned itself with ideology and extractive money interests. A design movement that ignores living structure took dominance after World War II. It thrives through global consumption. Mathematical analysis can measure very precise living qualities embedded in design and materials, such as fractal scaling, multiple nested symmetries, color harmonization, organized details, vertical axis, etc. Recent experimental tools of eye-tracking and artificial intelligence using Visual Attention Software determine which designs attract the eye unconsciously, and which remain uninteresting to our sophisticated brain evolved for survival.

[…]

After the Second World War, the architecture-industrial complex of building and real estate industries began a massive rebuilding of major cities. This freed up real estate for new construction, an activity that enriched a certain section of society. Working with politicians at all levels, architectural review boards did not value traditional buildings, nor those in any of several new but non-modernist form languages. Any qualms about the irreversible destruction of the life of cities were offset by the media convincing the population that this was an inexorable and much desired move towards progress. Anybody opposing this program of architectural substitution — replacing living by dead structure — was labeled an obscurantist reactionary. The promised utopia seduced academia to join this campaign. People failed to realize that an ideology ostensibly linked to Marxist beliefs was driven by ruthless industry manipulation.

Nevertheless, architects don’t tear down buildings: it is real estate speculators who do. Those corporate entities are amoral, willing to do anything for profit. It’s not their responsibility to save valuable older buildings; that task falls upon society, which has failed miserably in this duty. The various mechanisms that are supposed to protect a perfectly sound and health-inducing building become a cruel joke when such a building is demolished. A decision is taken outside the light of public scrutiny, while implementing the strategy of the fait accompli — after the bulldozers and wreckers, it’s too late to do anything.

The story of the systematic destruction of the UK’s architectural heritage is long and ugly. To mention just one example, the corrupt Newcastle City Council Member Thomas Daniel Smith managed to erase large swaths of central city districts and replace them with cheaply-built glass-and-steel monstrosities before he was jailed in 1974. Smith worked closely with dishonest — and extremely successful — architect John Poulson, who was also jailed in 1974. He appealed directly to democratic and liberal sentiments to further his ambitions, and the political class at the time fell for his manipulations. This sordid story repeats, with only minor variations, except that the other urbanicides were never prosecuted.

December 4, 2021

QotD: Still making dystopia

It is now three years since James Stevens Curl’s Making Dystopia was first published. Professor Curl’s book revised the history of architecture in the 20th century, exposing the standard curriculum taught to students as a poorly-conceived fabrication. The truth, backed by the mountains of evidence he cited, was frightening.

Curl’s critique of the theory and practice of modernism demolished the economical-ethical-political arguments put forward for decades that justified forcing people to live in inhuman environments. It was all a power-play, to drive humane architecture and its practitioners into the ground so that a new group of not very competent architects and academics could take over.

Alas, after three years, the situation is much the same as it was before 2018. Whoever practised humane architecture continues to do so today. Practitioners who have always applied Curl’s philosophy include Classical and Traditional architects, and followers of Christopher Alexander (who do not necessarily use a Classical style, but reject the modernist design straightjacket so as to create a more living structure). Those who produced image-based inhumane architecture have not changed tack or been influenced in any perceivable way.

Curl’s book covers human-scale developments that were allowed at the margins of the profession during several decades, as long as they didn’t threaten the core where the spotlight shines. Practitioners the world over, most often working in isolation, produce excellent and humane buildings. That work is hardly ever seen in the media, certainly never in the architecture journals. I’m sure that those architects now feel vindicated. It is possible that Curl’s book provides a rallying point for those who desire a new, humane architecture.

Nikos A. Salingaros, “Still making dystopia”, The Critic, 2021-08-30.

June 13, 2021

QotD: Defending the undefendable – Brutalist architecture

I have recently collected quite a number of articles online and in the press in favor of brutalism. I did so without having made any special effort, and without finding anything like the same number of countervailing articles against it, albeit that the great mass of the population, in my view rightly, detests brutalism. The penultimate paragraph of one of the recent articles that I have seen in favor of brutalism — the employment of great slabs of concrete in the construction of buildings — goes as follows:

The newly-gained attractivity [of architectural brutalism] is growing by the day. In troubled times where societal divides are stronger than ever around the globe and in a world where instantaneous rhymes with tenuous, brutalism offers a grounded style. It’s a simple, massive and timeless base upon which one can feel safe, it’s reassuring.

It is rather difficult to argue with, let alone refute, the vague propositions of such a paragraph, which nevertheless intends (I imagine) to connote approval and judgment based upon sophisticated, wide, and deep intellectual considerations. But what exactly is a “grounded style” in contrast to a “world where instantaneous rhymes with tenuous”? This is verbiage, if not outright verbigeration, though it might serve to intimidate those with little confidence in their own judgment. The idea that brute concrete could create any kind of security rather than unease or fear is laughable.

When defenders of or apologists for brutalism illustrate their articles with supposed masterpieces of the genre, it is hardly a coincidence that they do so with pictures of buildings utterly devoid of human beings. A human being would be about as out of place in such a picture, and a fortiori in such a building, as he would be in a textbook of Euclidean geometry, and would be as welcome as a termite in a wooden floor or a policeman in a thieves’ kitchen. For such defenders and apologists of brutalism, architecture is a matter of the application of an abstract principle alone, and they see the results through the lenses of their abstraction, which they cherish as others cherish their pet.

Theodore Dalrymple, “The Brutalist Strain”, Taki’s Magazine, 2019-11-02.

May 31, 2021

QotD: Contemporary architecture hates you

The fact is, contemporary architecture gives most regular humans the heebie-jeebies. Try telling that to architects and their acolytes, though, and you’ll get an earful about why your feeling is misguided, the product of some embarrassing misconception about architectural principles. One defense, typically, is that these eyesores are, in reality, incredible feats of engineering. After all, “blobitecture” — which, we regret to say, is a real school of contemporary architecture — is created using complicated computer-driven algorithms! You may think the ensuing blob-structure looks like a tentacled turd, or a crumpled kleenex, but that’s because you don’t have an architect’s trained eye.

Another thing you will often hear from design-school types is that contemporary architecture is honest. It doesn’t rely on the forms and usages of the past, and it is not interested in coddling you and your dumb feelings. Wake up, sheeple! Your boss hates you, and your bloodsucking landlord too, and your government fully intends to grind you between its gears. That’s the world we live in! Get used to it! Fans of Brutalism — the blocky-industrial-concrete school of architecture — are quick to emphasize that these buildings tell it like it is, as if this somehow excused the fact that they look, at best, dreary, and, at worst, like the headquarters of some kind of post-apocalyptic totalitarian dictatorship.

Brianna Rennix and Nathan J. Robinson, “Why You Hate Contemporary Architecture”, Current Affairs, 2017-10-31.

May 26, 2021

QotD: Modern architecture is ugly … or worse

The British author Douglas Adams had this to say about airports: “Airports are ugly. Some are very ugly. Some attain a degree of ugliness that can only be the result of special effort.” Sadly, this truth is not applicable merely to airports: it can also be said of most contemporary architecture.

Take the Tour Montparnasse, a black, slickly glass-panelled skyscraper, looming over the beautiful Paris cityscape like a giant domino waiting to fall. Parisians hated it so much that the city was subsequently forced to enact an ordinance forbidding any further skyscrapers higher than 36 meters.

Or take Boston’s City Hall Plaza. Downtown Boston is generally an attractive place, with old buildings and a waterfront and a beautiful public garden. But Boston’s City Hall is a hideous concrete edifice of mind-bogglingly inscrutable shape, like an ominous component found left over after you’ve painstakingly assembled a complicated household appliance. In the 1960s, before the first batch of concrete had even dried in the mold, people were already begging preemptively for the damn thing to be torn down. There’s a whole additional complex of equally unpleasant federal buildings attached to the same plaza, designed by Walter Gropius, an architect whose chuckle-inducing surname belies the utter cheerlessness of his designs. The John F. Kennedy Building, for example — featurelessly grim on the outside, infuriatingly unnavigable on the inside — is where, among other things, terrified immigrants attend their deportation hearings, and where traumatized veterans come to apply for benefits. Such an inhospitable building sends a very clear message, which is: the government wants its lowly supplicants to feel confused, alienated, and afraid.

Brianna Rennix and Nathan J. Robinson, “Why You Hate Contemporary Architecture”, Current Affairs, 2017-10-31.

February 15, 2020

QotD: Architecture’s lingering racism

Many leading 20th-century architects, including Philip Johnson and Mies van der Rohe, were openly disdainful of the public’s preferences. On occasion they evinced subtle and overt racism. In 1913, in one of the most influential essays in the history of Modernist architecture, “Ornament and Crime,” the Austrian architect Adolf Loos declared that modern man (read: white northern Europeans) must go beyond what “any Negro” could achieve in design, and strip away all that is superfluous, all that is morally and spiritually polluted. It is Papuans and other primitives who, like innocent children, ornament themselves with tattoos. Loos’ race has superseded them: “the modern man who tattoos himself is either a criminal or a degenerate.” The same held for ornament in architecture. (To this day, architects — who continue to believe they are the vanguard of civilization’s progress — find ornament retrograde. Yet ordinary people stubbornly continue to adorn themselves with cosmetics, jewelry, and, yes, tattoos.)

In the 1920s, during the time he was a member of the French Fascist party, the seminal architect Le Corbusier said he was disgusted by the “zone of odours, [a] terrible and suffocating zone comparable to a field of gypsies crammed in their caravans amidst disorder and improvisation.” He also chimed in with Loos: “Decoration is of a sensorial and elementary order, as is color, and is suited to simple races, peasants, and savages … The peasant loves ornament and decorates his walls.”

More recently, indicative of architecture’s current race problem, in 2006 the aforementioned highly influential dean of Tulane’s architecture school, Reed Kroloff, wrote the embarrassingly tone-deaf, flat-footed essay “Black Like Me.” (As I discuss below, he collaborated with Betsky on a post-Katrina project.) Kroloff — the privileged, self-described gay white Jew from Waco, Texas — announced that he was now black, that the Hurricane Katrina disaster had made him feel first-hand the African-American predicament. His piece was subject to much ridicule. No wonder the Mods have chosen to insulate themselves from the un(brain)washed masses. Architecture has become a gated community.

Betsky, to his credit, doesn’t pretend that architects should even try to make outreach. Showing little sympathy for democracy, he says that appeals to the public are “mystical.” The people — the 99% — do not deserve a seat at the table. Yet Betsky would have us believe that he and the architecture he supports are “progressive.”

Justin Shubow, “Architecture Continues To Implode: More Insiders Admit The Profession Is Failing”, Forbes, 2015-01-06.

February 4, 2020

QotD: Brutalist “sincerity”

Apologists and defenders of brutalism often use astonishing arguments. Here, for example, is what an Australian wrote recently:

Unrefined concrete was an honest expression of [brutalist architects’] intentions, while plain forms and exposed structures were similarly sincere.

This is like saying that the Gulag was an honest expression of Stalin’s intentions. Sincerity of intentions is not a virtue irrespective of what those intentions are, and as a matter of fact those of the inspirer and founder of brutalism were clearly evil, as the slightest acquaintance with his writings will convince anyone of minimal decency. And what exactly is “sincerity of form and exposed structures”? Is it meant to imply that anything other than brutalism is insincere?

The same article continues:

Beyond their architectural function, Brutalist buildings serve other uses. Skateboarders, graffiti artists and parkour practitioners, for example, have all used Brutalism’s concrete surfaces in innovative ways.

Dear God! I have nothing against playgrounds — they are socially commendable, especially for children — but to regard the urban fabric as properly an extended playground is surely to infantilize the population. As for graffiti artists, to regard the extension of their “canvas” to large public buildings is an abject surrender to vandalism. No one, I presume, would say of a wall, “And in addition it would make an excellent place for a firing squad.”

Theodore Dalrymple, “The Brutalist Strain”, Taki’s Magazine, 2019-11-02.

January 23, 2020

January 7, 2020

QotD: The cult of Le Corbusier

What accounts for the survival of this cold current of architecture that has done so much to disenchant the urban world — the original modernism having been succeeded by different styles, but all of them just as lizard-eyed? According to Curl, the profession of architecture has become a cult. It is worth quoting him in extenso:

A dangerous cult may be defined as a kind of false religion, adoption of a system of belief based on mere assertions with no factual foundations, or as excessive, almost idolatrous, admiration for a person, persons, an idea, or even a fad. The adulation accorded to Le Corbusier, accorded almost the status of a deity in architectural circles, is just one example. It has certain characteristics which may be summarized as follows: it is destructive; it isolates its believers; it claims superior knowledge and morality; it demands subservience, conformity, and obedience; it is adept at brainwashing; it imposes its own assertions as dogma, and will not countenance any dissent; it is self-referential; and it invents its own arcane language, incomprehensible to outsiders.

Anyone who thinks this is an exaggeration has not read much Le Corbusier. (His writing is as bad as his architecture, and bears out precisely what Curl says.) Nor is it difficult to find in the architectural press examples of cultish writing that is impenetrable and arcane, devoid of denotation but with plenty of connotation. Here, for example, is Owen Hatherley, writing about an exhibition of Le Corbusier’s work at London’s Barbican Centre (itself a fine example of architectural barbarism). According to Hatherley, Le Corbusier was:

the architect who transformed buildings for communal life from mere filing cabinets into structures of raw, practically sexual physicality, then forced these bulging, anthropomorphic forms into rigid, disciplined grids. This might be the work of the “Swiss psychotic” at his fiercest, but the exhibition’s setting, the Barbican — with its bristly concrete columns and bullhorn profiles, its walkways and units — proves that even its derivatives can become places rich with perversity and intrigue, without a pissed-in lift [elevator] or a loitering youth in sight. … [T]hese collisions of collectivity and carnality have no obvious successors today.

Theodore Dalrymple, “Crimes in Concrete”, First Things, 2019-06.

January 4, 2020

QotD: “Starchitects”

In my school, the status of “Corb” (as we were encouraged to affectionately call him) as a hero was a given, and dissenting from this position was risky. Such is the power of group-think which universities are, sadly, no less prone to than anywhere else. To be fair, nobody was still plugging the megalomaniac aspect of their hero; his knock-down-the-center-of-Paris side. All those undeniably God-awful tower blocks for “rationally” housing “the people” that sprang up all over Europe in his name? Well, we were assured, they could not be blamed on Corb; it was just that his more pedestrian architectural acolytes hadn’t properly understood what he had meant. In addition to the persistence of Corb-hero worship itself, two cancerous aspects of its radical mindset have survived intact in our schools of architecture.

One is the idea that an architect aspiring to greatness must also aspire to novelty. It is this imperative to “innovate” that underpins the diagrammatic design concepts of the Deconstuctivists. There is of course nothing wrong with innovation per se; it is the knee-jerk compulsion to innovate, or “reinterpret” — as a kind of moral imperative — that is the mid-20th-century aesthetic legacy. To be fair to the profession, I would come to the defense of much innovative public and commercial architecture, most of it by architects that the public has never heard of. Tragically though, these unpretentious and unsung essays in steel, glass, and masonry have been eclipsed in the public imagination by the “starchitect” bling that is currently turning the centers of our great cities into a collection of (in James Stevens Curl’s memorable phrase) “California-style roadside attractions”.

The other cancer is the idea that building design has sociological, psychological, and macro-economic dimensions that the architect — simply by virtue of being an architect — is competent to judge. What really matters to your average architecture student is drawing — which is fine, and just as it should be, until the vain idea emerges that their drawings represent some kind of implicit vision for mankind. At my school, any student’s design presentation had to include a verbal rationale — often post hoc and invariably half-baked — of how the form, massing, and materials of the design are expressive of such imponderables as the supposed psychological “needs” and “aspirations” of the users and the wider “community” that the building is to serve. The students were simply reciting the bogus language of their tutors — in which buildings might be said to be “fun,” “thought provoking,” “democratic,” “inclusive” and other such nonsense.

Graham Cunningham, “Why Architectural Elites Love Ugly Buildings”, The American Conservative, 2019-11-01.