The normal expectation for Greek tyranny is that the system works like the Empire from Star Wars: A New Hope, where the new tyrant abolishes the Senate, appoints his own cronies to formal positions as rulers and generally makes himself Very Obviously and Formally In Charge. But this isn’t how tyranny generally worked: the tyrant was Very Obviously but not formally in charge, because he ruled extra-constitutionally, rather than abolishing the constitution. This is what separates tyranny, a form of extra-constitutional one man rule, from monarchy, a form of traditional and thus constitutional one-man rule.

We see the first major wave of tyrannies emerging in Greek poleis in the sixth century, although this is also about the horizon where we can see political developments generally in the Greek world, still our sources seem to understand this development to have been somewhat novel at the time and it is certainly tempting to see the emergence of tyranny and democracy in this period both as responses to the same sorts of pressures and fragility found in traditional polis oligarchies, but again our evidence is thin. Tyrants tend to come from the elite, oligarchic class and often utilize anti-oligarchic movements (civil strife or stasis, στάσις) to come to power.

Because most poleis are small, the amount of force a tyrant needed to seize power was also often small. Polycrates supposedly seized power in Samos with just fifteen soldiers (Hdt. 3.120), though we may doubt the truth of the report and elsewhere Herodotus notes that he did so in conspiracy with his two brothers of whom he killed one and banished the other (Hdt. 3.39). I’ve discussed Peisistratos’ takeover(s) in Athens before but they were similarly small-ball affairs. In Corinth, Cypselus seized power by using his position as polemarch (war leader) to have the army (which, remember, is going to be a collection of the non-elite but still well-to-do citizenry, although this is early enough that if I call it a hoplite phalanx I’ll have an argument on my hands) expel the Bacchiadae, a closed single-clan oligarchy. A move by any member of the elite to put together their own bodyguard (even one just armed with clubs) was a fairly clear indicator of an attempt to form a tyranny and the continued maintenance of a bodyguard was a staple of how the Greeks understood a tyrant.

Having seized power, those tyrants do not seem to have abolished key civic institutions: they do not disband the ekklesia or the law courts. Instead, the tyrant controls these things by co-opting the remaining elite families, using violence and the threat of violence against those who would resist and installing cronies in positions of power. Tyrants also seem to have bought a degree of public acquiescence from the demos by generally targeting the oligoi, as with Cypselus and his son Periander killing and banishing the elite Bacchiadae from Corinth (Hdt. 5.92). But this is a system of government where in practice the laws appeared to still be in force and the major institutions appeared to still be functioning but that in practice the tyrant, with his co-opted elites, armed bodyguard and well-rewarded cadre of followers among the demos, monopolized power. And it isn’t hard to see how the fiction of a functioning polis government could be a useful tool for a tyrant to maintain power.

That extra-constitutional nature of tyranny, where the tyrant exists outside of the formal political system (even though he may hold a formal office of some sort) also seems to have contributed to tyranny’s fragility. Thales was supposedly asked what the strangest thing he had ever seen was and his answer was, “An aged tyrant” (Diog. Laert. 1.6.36) and indeed tyranny was fragile. Tyrants struggled to hold power and while most seem to have tried to pass that power to an heir, few succeed; no tyrant ever achieves the dream of establishing a stable, monarchical dynasty. Instead, tyrants tend to be overthrown, leading to a return to either democratic or oligarchic polis government, since the institutions of those forms of government remained.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: How to Polis, 101, Part IIa: Politeia in the Polis”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2023-03-17.

March 20, 2024

QotD: Ancient Greek tyranny

March 14, 2024

QotD: Recruiting an army in the Roman Republic

Before we dive in, we should stop to clarify some of our key actors here, the Roman magistrates and officers with a role in all of this. A Roman army consisted of one or more legions, supported by a number (usually two) alae recruited from Rome’s Italian allies, the socii. Legions in the Republic did not have specific commanders, rather the whole army was commanded by a single magistrate with imperium (the power to command armies and organize courts). That magistrate was usually a consul (of which there were two every year), but praetors and dictators,1 all had imperium and so might lead an army. Generally the consuls lead the main two armies. When more commanders were needed, former consuls and praetors might be delegated the job as a stand-in for the current magistrates, these were called pro-consuls and pro-praetors (or collectively, “pro-magistrates”) and they had imperium too.

In addition to the imperium-haver leading the army, there were also a set of staff officers called military tribunes, important to the process. These fellows don’t have command of a specific part of the legion, but are “officers without portfolio”, handling whatever the imperium-haver wants handled; at times they may have command of part of a legion or all of one legion. Finally, there’s one more major magistrate in the army: the quaestor. A much more junior magistrate than the imperium-haver (but senior to the tribunes), he handles pay and probably in this period also supply. That said, the quaestor is not usually the general’s “number two” even though it seems like he might be; quaestors are quite junior magistrates and the imperium-haver has probably brought friends or advisors with a lot more experience than his quaestor (who may or may not be someone the imperium-haver knows or likes). […]

The first thing to note about this process, before we even start is that the dilectus was a regular process which happened every year at a regular time. The Romans did have a system to rapidly raise new troops in an emergency (it was called a tumultus), where the main officials, the consuls, could just grab any citizen into their army in a major emergency. But emergencies like that were very rare; for the most part the Roman army was filled out by the regular process of the dilectus, which happened annually in tune with Rome’s political calendar. That regularity is going to be important to understand how this process is able to move so many people around: because it is regular, people could adapt their schedules and make provisions for a process that happened every year. I should note the dilectus could also be held out of season, though often the times we hear about this it is because it went poorly (e.g. in 275 BC, no one shows up).

The process really begins with the consular elections for the year, which bounced around a little in the calendar but generally happened around September,2 though the consuls do not take office until the start of the next calendar year. As we’ve discussed, the year originally seems to have started in March (and so consuls were inaugurated then), but in 153 was shifted to January (and so consuls were inaugurated then).

What’s really clear is that there is some standard business that happens as the year turns over every year in the Middle Republic and we can see this in the way that Livy structures his history, with year-breaks signaled by these events: the inauguration of new consuls, the assignment of senior Roman magistrates and pro-magistrates to provinces, and the determinations of how forces will be allotted between those provinces. And that sequence makes a lot of sense: once the Senate knows who has been elected, it can assign provinces to them for the coming year (the law requiring Senate province assignments to be blind to who was elected, the lex Sempronia de provinciis consularibus, was only passed in 123) and then allocate troops to them. That allocation (which also, by the by, includes redirecting food supplies from one theater to another, as Rome is often militarily actively in multiple places) includes both existing formations, but is also going to include the raising of new legions or the conscription of new troops to fill out existing legions, a practice Livy notes.

The consuls, now inaugurated have another key task before they can embark on the dilectus, which is the selection of military tribunes, a set of staff officers who assist the consuls and other magistrates leading armies. There are six military tribunes per legion (so 24 in a normal year where each consul enrolls two legions); by this point four are elected and two are appointed by the consul. The military tribunes themselves seem to have often been a mix, some of them being relatively inexperienced aristocrats doing their military service in the most prestigious way possible and getting command experience, while Polybius also notes that some military tribunes were required to have already had a decade in the ranks when selected (Polyb. 6.19.1). These fellows have to be selected first because they clearly matter for the process as it goes forward.

The end of this process, which as we’ll see takes place over several days at least, though exactly how many is unclear, will have have had to have taken place in or before March, the Roman month of Martius, which opened the normal campaigning season with a bunch of festivals on the Kalends (the first day of the month) to Mars. As Rome’s wars grew more distant and its domestic affairs more complex, it’s not surprising that the Romans opted to shift where the year began on the calendar to give the new consuls a bit more of winter to work with before they would be departing Rome with their armies. It should be noted that while Roman warfare was seasonal, it was only weakly so: Roman armies stayed deployed all year round in the Middle Republic, but serious operations generally waited until spring when forage and fodder would be more available.

That in turn also means that the dilectus is taking place in winter, which also matters for understanding the process: this is a low-ebb in the labor demands in the agricultural calendar. I find it striking that Rome’s elections happen in late summer or early fall, when it would actually be rather inconvenient for poor Romans to spend a day voting (it’s the planting season), but the dilectus is placed over winter where it would be far easier to get everyone to show up. I doubt this contrast was accidental; the Roman election system is quite intentionally designed to preference the votes of wealthier Romans in quite a few ways.

So before the dilectus begins, we have our regular sequence: the consuls are inaugurated at the beginning of the year, the Senate meets and assigns provinces and sets military priorities, including how many soldiers are to be enrolled. The Senate’s advice is not technically legally binding, but in this period is almost always obeyed. Military tribunes are selected (some by election, some by appointment) and at last the consuls can announce the day of the dilectus, conveniently now falling in the first couple of months of the year when the demand for agricultural labor is low and thus everyone, in theory, can afford to show up for the selection process.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: How To Raise a Roman Army: The Dilectus“, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2023-06-16.

1. And the dictator’s master of the horse.

2. On this, see J.T. Ramsey, “The Date of the Consular Elections in 63 and the Inception of Catiline’s Conspiracy”, HSCP 110 (2019): 213-270.

March 8, 2024

QotD: The original greasy pole of the cursus honorum

Last week we discussed the overall structure of the “career path” for a Roman politician and the first few offices along that path. This week we’re going to look at the upper-steps of that career path, the offices of praetor and consul and the particular set of powers they possess, called imperium, along with the pro-magistrate forms of these positions. Now I should note at the outset that we have skipped one office on our way through, the tribunes of the plebs; we’ll get to that office next week to discuss its oddities and unusual powers.

The praetorship and the consulship are the highest Roman offices (the censorship being more of a “victory lap”) and the two offices that wield direct military and judicial authority. These are also the offices where competition in the cursus honorum starts to get fierce, as the eight quaestors must compete for just six praetorships and those six praetors can expect to compete for just two – always two – consulships. It is worth keeping in mind as we go through this that on the one hand these offices are largely confined to a small Roman elite, the nobiles, composed of families (both patrician and plebeian) that have been successful in politics over generations, but at the same time it is the popular assemblies which choose “winners” and “losers” from among the nobiles by deciding who gets to proceed to the next round of the political elimination context, and who is forever going to sit in the Senate as a former quaestor and nothing more.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: How to Roman Republic 101, Part IIIb: Imperium”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2023-08-18.

Update: I forgot to add the glossary links. Fixed now.

March 5, 2024

The 1st Punic War – Corvus, Rams and Drachma

Drachinifel

Published Sep 13, 2023Today we take a look at the strategy and shipping of the 1st Punic War with expert Bret Devereaux!

(more…)

March 2, 2024

QotD: Early siege warfare

Now the besieger’s side of the equation may seem like an odd place to start a primer on fortifications, but it actually makes a fair bit of sense, because the capabilities of a potential attacker is where most thinking about fortification begins. Siegecraft, both offensive and defensive, is a case of “antagonistic co-evolution“, a form of evolution through opposition where each side of the relationship evolves new features in response to the other: neither offensive siege techniques nor fortifications evolve in isolation but rather in response to each other.

In many ways the choice of where to begin following that process of evolution is arbitrary. We could in theory start anywhere from the very distant past or only very recently, but in this case I think it makes sense to begin with the early Near Eastern iron age because of the nature of our evidence. While it is clear that siege warfare must have been an important part of not only bronze age warfare but even pre-bronze age warfare, sources for the details of its practice in that era are sparse (in part because, as we’ll see, siege warfare was a sort of job done by lower status soldiers who often didn’t figure much into artwork focused on royal self-representation and legitimacy-building).

But as we move into the iron age, the dominant power that emerges in the Near East is the (Neo-)Assyrian Empire, the rulers of which make a point of foregrounding their siegecraft as part of a broader program of discouraging revolt by stressing the fearsome abilities of the Assyrian army (which in turn had much of its strength in its professional infantry). Consequently, we have some very useful artistic depictions of the Assyrian army doing siege work and at the same time some incomplete but still very useful information about the structure of the army itself. Moreover, it is just as the Assyrian Empire’s day is coming to a close (collapse in 609) that the surviving source base begins to grow markedly more robust (particularly, but not exclusively, in Greece), giving us dense descriptions of siege work (and even some manuals concerning it) in the following centuries, which we can in turn bring to the Assyrian evidence to better understand it. So this is a good place to start because it is the earliest point where we are really on firm ground in terms of understanding siegecraft in some detail. This does mean we are starting in medias res, with sophisticated states already using complex armies to assault fairly complex, sophisticated fortifications, which is worth keeping in mind.

That said, it should be noted that this is hardly beginning at the beginning. The earliest fortifications in most regions of the world were wooden and probably very simple (often just a palisade with perhaps an elevated watch-post), but by the late 8th century, well-defended sites (like walled cities) already sported sophisticated systems of stone walls and towers for defense. That caveat is in turn necessary because siegecraft didn’t evolve the same way everywhere: precisely because this is a system of antagonistic co-evolution it means that in places where either offensive or defensive methods (or technologies) took a different turn, one can end up with very different results down the line (something we’ll see especially with gunpowder).

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Fortification, Part I: The Besieger’s Playbook”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-10-29.

February 25, 2024

QotD: From the M1903 Springfield to the M1 Garand

The M1 Garand is correctly considered the best battle rifle of World War II. It was the only semi-automatic rifle — meaning that it fired each time the operator pulled the trigger — to be the standard issue infantry rifle of any army during the war. Other forces were equipped with bolt-action rifles — the British Lee Enfield, Soviet Mosin Nagant, Japanese Type 99, German K98k, etc. — that required the operator to manually pull back a bolt to eject the [expended cartridge], and then push it forward again to insert a fresh cartridge into the chamber. The most obvious advantage was an increased rate of fire: a semiautomatic rifleman with an M1 had an official aimed rate of fire of 24 shots per minute.1 Compare this to the 15 aimed shots that British soldiers were expected to pop off with a bolt-action Lee Enfield in a “mad minute” drill. And the Lee Enfield was one of the fastest bolt-action rifles ever produced! In a pinch, a GI could blast out a clip in a few seconds, approximating a burst from an automatic weapon.2 Furthermore, with semi-automatic fire, the shooter could stay focused on his target, whereas working the bolt generally forced the shooter off target, requiring time to reacquire a proper sight picture.

Lt. General George Patton famously called the M1 Garand “the greatest battle implement ever devised“, a quote often repeated reverently in the context of World War II nostalgia. The US Government after the war gave away millions of M1 Garands, making it a popular civilian rifle for hunting and competitive shooting.

But nostalgia aside, it is also possible to view, from the high perch of hindsight, the M1 Garand as a missed opportunity. The most advanced battle rifle of World War II ultimately looked back too much to the past rather than pointing the way to the future. During its development, senior military officials applied the perceived lessons of the Spanish American War to a rifle designed to solve the problems of the Great War. This intervention prevented the M1 Garand from becoming something closer to a modern assault rifle, with an intermediate power cartridge and higher magazine capacity. The army was in no hurry to ditch the rifle that had won World War II, meaning that the United States did not field its first true assault rifle until two decades after the concept had been invented by the Germans in 1943 and soon successfully adapted by the Soviets in 1947. The first American assault rifle, the M16, would not debut until 1965.

First a necessary caveat: rifles were not the decisive weapon in World War II. For the most part the small arms deployed by the United States had been designed to fight World War I: the Browning Automatic Rifle (1918), the M1919 Browning Medium Machine Gun (as the date implies, first fielded in 1919) and the M2 Browning heavy machine gun, designed in 1918 and so good it is still used over a century later. In contrast, German machine guns were somewhat more recent in design: the MG 34 (as the name implies, first fielded 1934) and the MG 42. During the war, the Germans invented the first true assault rifle, the StG 44.

The secret sauce of the US Army by 1944-45 had little to do with firearms at all: it was a combination of ready mobility through motorization combined with deadly artillery and close air support, enabled by an unmatched communication system that allowed forward observers to direct and adjust fires to lethal effect. The American way of war was rooted in fleets of trucks and jeeps, networks of radios and heaps of shells. Having a nice semi-automatic rifle was ancillary to a conflict like World War II. But the M1 Garand is a useful window into the vagaries of military procurement and technological innovation, which require developers to at once predict the operational environment of the future and analyze the lessons of the past.

Throughout the 1920s, officers at the Infantry School in Fort Benning experimented with new tactics that they hoped would again allow for mobile infantry combat and avoid the trench stalemate of World War I. The basic solution was some form of “fire and maneuver”, in which one section of a unit (say a squad or platoon) would lay down a sufficient base of small arms fire to suppress the enemy so as to facilitate the other section’s advance. By alternating suppression and assault the element might leapfrog its way forward, even against entrenched enemy machine guns.

For such a tactic to work, infantry platoons needed a lot of firepower. Some might come from light machine guns, like the Browning Automatic Rifle, which was issued to individual infantry squads. But it was generally realized that individual infantrymen needed to be capable of a far higher rate of fire than could be provided by the standard issue rifle, the bolt-action M1903 Springfield, fed from a five round magazine. To this end, the US government set about developing a semi-automatic rifle.

The charge was taken up by John C. Garand, a Canadian-born, self taught firearms designer who worked for the Springfield Armory in Massachusetts. Garand’s solution to make the rifle self-loading was to insert a piston beneath the barrel. When the gunpowder exploded in the cartridge, the gas produced in the explosion propelled the bullet out the barrel. But some gas was bled off into a cylinder below the barrel (which gives the M1 its peculiar appearance of seeming to have two barrels); the pressure of the gas in the cylinder drove a piston.3 This piston attached to an operating rod which pushed the bolt of the rifle back, ejecting the spent casing, and allowing a spring in the internal magazine to insert another cartridge into the chamber before a separate spring pushed the operating rod forward and closed the bolt for the next shot, all in a fraction of a second.

Garand had initially worked on a rifle chambering the standard .30-06 cartridge used by the M1903 Springfield rifle (the .30 indicates that the bullet had a diameter of .30 inches, while the 06 indicates that the cartridge had been adopted in 1906; the round is often pronounced “thirty-ought-six”. But when a rival designer named John Pedersen, also affiliated with Springfield Armory, developed a semi-automatic design that chambered a lighter .276 (7mm) round, Garand retooled his project for the lighter round as well, producing a prototype known as the T3, with subsequent refinements labeled the T3E1 and T3E2. The smaller round meant that the internal magazine of the T3E1/2 could accept clips of 10 bullets, doubling the magazine capacity of the M1903 Springfield.

Army officials were very interested in the new round, but wanted proof that a lighter bullet would be sufficiently lethal in combat. A series of grisly ballistic tests were therefore ordered, pitting the .276 round against the traditional .30-06. In 1928, anesthetized pigs were shot through with both rounds. To the surprise and consternation of traditionalists, the .276 did far more damage in the so-called “Pig Board”. This is not paradoxical: the lighter round was more likely to “tumble”, precisely because it was lighter and so more likely to have its trajectory disrupted by bone and tissue; the tumble meant that more of the kinetic energy was expended inside the target, causing far more damage. The .30-06, meanwhile, as a more powerful round, was more likely to punch clean through, retaining its kinetic energy to keep moving forward after passing through the target. Eventually, tests of this sort would be used to sell the army on the lethality of the 5.56mm round used by the M16/M4, which has an even greater tumble, and causes even more grievous injuries. Out of concern that the fat bodies of pigs did not accurately replicate the human teenagers that the new round was designed to kill, a new test was inflicted upon goats, seen as more appropriately lean and therefore better analogs. The result was the same in favor of the .276 (a lighter .256 performed even better). With two rounds of tests vindicating the .276, the Army demanded that its new rifle chamber the .30-06. The final decision was made by Douglas MacArthur himself.

The .30-06 round itself had been the product of a painful lesson learned during the Spanish American War. Here, American troops, armed with Krag M1892 rifles, had found themselves badly out-ranged by Spanish troops armed with Mausers; the famous charge up San Juan Hill occurred after US troops had advanced for some distance under a hail of unanswered rifle fire. Given the importance of sharp shooting to the American military mythos, getting handily outranged and outshot by Spanish forces was a painful embarrassment. The first order of business had been to adopt the Mauser design: the M1903 Springfield was essentially a modified Mauser, as the US government had licensed a number of Mauser’s patents. By upgrading the M1903 to take the heavy .30-06 round, the Army ensured that soldiers could engage targets over a kilometer away. Beyond the deeply ingrained “lessons learned” from the Spanish American War, the mythos of the deadly American sharpshooter was strongly entrenched. Even as disruptors at Benning developed new infantry tactics that stressed volume of fire over accuracy, the phantoms of buck skinned frontiersmen sniping at British redcoats from a thousand paces still occupied the headspace of military leaders; they wanted a rifle with long distance accuracy. The sights on the M1 Garand adjust out to 1200 yards.

But MacArthur’s reasoning seems to have been primarily motivated by administrative and logistical concerns, as he cited the generic difficulties of fielding a lighter round. Some of these challenges may have been related to production and distribution of a sufficient stockpile of new caliber ammunition. There may have also been a concern with the new round complicating the logistics of line companies. The army also used .30-06 for the BAR and Browning medium machine gun, and having all of these shoot the same round in theory simplified the supply of line companies, and allowed for cross-leveling between weapons systems. Similar concerns have the US Army maintaining a policy of only having 5.56mm weapons at the squad level (thus the M4 and M249 Squad Automatic Weapon both shoot 5.56, and the SAW can shoot from M4 magazines).4 Still, MacArthur’s concerns seem unfounded in hindsight. The United States was about to produce billions of bullets during World War II. American troops were about to be so lavishly supplied that distributing two types of bullets would have been readily feasible given the soon to be proven quality of American logistics.5

With MacArthur’s edict, Garand retooled his rifle back to the .30-06 caliber, and his design was finally accepted in 1936. But the larger and more powerful round required a design change: the internal magazine now took clips of eight bullets instead of ten. Two rounds may not sound like much, but every bullet can be precious in a firefight, and this represented a 20% reduction in magazine capacity. Spread over a company sized element, the reduced clip capacity represented over two-thousand fewer rounds that a company commander could expect to fire and maneuver with. Indeed, the M1’s volume of fire proved generally insufficient to suppress the enemy on its own during the war, evidenced by the habit of equipping rifle squads with two Browning Automatic Rifles, instead of one. Marine divisions by the end of the war often deployed three BARs per squad.6

Michael Taylor, “Michael Taylor on The Development of the M1 Garand and its Implications”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2023-09-08.

1. TM 9-1005-222-12.

2. Thus George Wilson, a platoon leader and later company commander in the Fourth Infantry Division, describing a platoon scout stumbling upon the enemy: “The second scout emptied the eight round clip in his M-1 so fast it seemed like a machine gun … the rest of us moved very cautiously and found three dead enemy soldiers in the road.” (G. Wilson. If You Survive. Ivy, 1987).

3. John Garand’s initial design, and early production M1s, had a gas trap inserted over the muzzle to catch the gas after the bullet had exited; when this proved prone to fouling, a design modification drilled a small hole in the barrel just before the muzzle to allow the gas to bleed into the cylinder, most M1 Garands had this “gas port” system.

4. In 2023, US Army infantry will begin transition to the M7 carbine and M250 Squad Automatic weapon, which will both use a 6.8mm bullet, out of concerns that the 5.56 NATO is insufficient to penetrate body armor.

5. Editor’s Note: I agree with Michael here in principle: US logistics could have managed this. But I would also note that part of the reason American logistics were so good is that they applied MacArthur’s reasoning to everything, reusing vehicle chassis, limiting the number of different ammunition calibers and demanding interchangeable parts across the whole range of military equipment. Take one of those decisions away and the whole still functions. Take all of them away and one ends up with the mess that was German production and logistics.

6. Editor’s Note: BAR goes BARRRRRRRRRRR.

February 19, 2024

QotD: Cleopatra VII Philopator

This week on the blog we’re going to talk about Cleopatra or to be more specific, we’re going to talk about Cleopatra VII Philopator, who is the only Cleopatra you’ve likely ever heard of, but that “seven” after her name should signal that she’s not the only Cleopatra.1 One of the trends in scholarship over the years towards larger than life ancient historical figures – Caesar, Alexander, Octavian, etc. – has been attempts to demystify them, stripping away centuries of caked-on reception, assumptions and imitation to ask more directly: who was this person, what did they do and do we value those sorts of things?2

Cleopatra, of course, has all of that reception layered on too. In antiquity and indeed until the modern era, she was one of the great villains of history, the licentious, wicked foreign queen of Octavian’s propaganda. More recently there has been an effort to reinvent her as an icon of modern values, perhaps most visible lately in Netflix’ recent (quite poorly received) documentary series. A lot of both efforts rely on reading into gaps in the source material. What I want to do here instead is to try to strip some of that away, to de-mystify Cleopatra and set out some of what we know and what we don’t know about her, with particular reference to the question I find most interesting: was Cleopatra actually a good or capable ruler?

Now a lot of the debate sparked by that Netflix series focused on what I find the rather uninteresting (but quite complicated) question of Cleopatra’s heritage or parentage or – heaven help us – her “race”. But I want to address this problem too, not because I care about the result but because I am deeply bothered by how confidently the result gets asserted by all sides and how swiftly those confident assertions are mobilized into categories that just aren’t very meaningful for understanding Cleopatra. To be frank, Cleopatra’s heritage should be a niche question debated in the pages of the Journal of Juristic Papyrology by scholars squinting at inscriptions and papyri, looking to make minor alterations in the prosopography of the Ptolemaic dynasty, both because it is highly technical and uncertain, but also because it isn’t an issue of central importance. So we’ll get that out of the way first in this essay and then get to my main point, which is this:

Cleopatra was, I’d argue, at best a mediocre ruler, whose ambitious and self-interested gambles mostly failed, to the ruin of herself and her kingdom. This is not to say Cleopatra was a weak or ineffective person; she was very obviously highly intelligent, learned, a virtuoso linguist, and a famously effective speaker. But one can be all of those things and not be a wise or skillful ruler, and I tend to view Cleopatra in that light.

Now I want to note the spirit in which I offer this essay. This is not a take-down of the Netflix Queen Cleopatra documentary (though it well deserves one and has received several; it is quite bad) nor a take-down of other scholars’ work on Cleopatra. This is simply my “take” on her reign. There’s enough we don’t know or barely know that another scholar, viewing from another angle, might well come away with a different conclusion, viewing Cleopatra in a more positive light. This is, to a degree, a response to some of the more recent public hagiography on Cleopatra, which I think air-brushes her failures and sometimes tries a bit too hard to read virtues into gaps in the evidence. But they are generally gaps in the evidence and in a situation where we are all to a degree making informed guesses, I am hardly going to trash someone who makes a perfectly plausible but somewhat differently informed guess. In history there are often situations where there is no right answer – meaning no answer we know to be true – but many wrong answers – answers we know to be false. I don’t claim to have the right answer, but I am frustrated by seeing so many very certain wrong answers floating around the public.

Before we dive in briefly to the boring question of Cleopatra’s parentage before the much more interesting question of her conduct as a ruler, we need to be clear about the difficult nature of the sources for Cleopatra and her reign. Fundamentally we may divide these sources into two groups: there are inscriptions, coins and papyrus records from Egypt which mention Cleopatra (and one she wrote on!) but, as such evidence is wont to be, [they] are often incomplete or provided only limited information. And then there are the literary sources, which are uniformly without exception hostile to Cleopatra. And I mean extremely hostile to Cleopatra, filled with wrath and invective. At no point, anywhere in the literary sources does Cleopatra get within a country mile of a fair shake and I am saying that as someone who thinks she wasn’t very good at her job.

The problem here is that Cleopatra was the target of Octavian’s PR campaign, as it were, in the run up to his war with Marcus Antonius (Marc Antony; I’m going to call him Marcus Antonius here), because as a foreign queen – an intersecting triad of concepts (foreignness, monarchy and women in power) which all offended Roman sensibilities – she was effectively the perfect target for a campaign aimed at winning over the populace of Italy, which was, it turns out, the most valuable military resource in the Mediterranean.3 That picture – the foreign queen corrupting the morals of good Romans with her decadence – rightly or wrongly ends up coloring all of the subsequent accounts. Of course that in turn effects the reliability of all of our literary sources and thus we must tread carefully.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: On the Reign of Cleopatra”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2023-05-26.

1. Or even just the seventh!

2. This is not to diminish the value of reception studies that trace the meaning a figure – or the memory of a figure – had over time. That’s a valuable but different lens of study.

3. It’s not all Octavian, mind. Cicero’s impression of Cleopatra was also sharply negative, for many of the same reasons: Cicero was hardly likely to be affable to a foreign queen who was an ally of Julius Caesar.

February 13, 2024

QotD: War elephant logistics

From trunk to tail, elephants are a logistics nightmare.

And that begins almost literally at birth. For areas where elephants are native, nature (combined, typically, with the local human terrain) create a local “supply”. In India this meant the elephant forests of North/North-Eastern India; the range of the North African elephant (Loxodonta africana pharaohensis, the most likely source of Ptolemaic and Carthaginian war elephants) is not known. Thus for many elephant-wielding powers, trade was going to always be a key source for the animals – either trade with far away kingdoms (the Seleucids traded with the Mauyran Indian kingdom for their superior Asian elephants) or with thinly ruled peripheral peoples who lived in the forests the elephants were native to.

(We’re about to get into some of the specifics of elephant biology. If you are curious on this topic, I am relying heavily on R. Sukumar, The Asian Elephant: Ecology and Management (1989). I’ve found that information on Asian elephants (Elephas maximus) much easier to come by than information on African elephants (Loxodonta africana and Loxodonta cyclotis).)

In that light, creating a breeding program – as was done with horses – seems like a great idea. Except there is one major problem: a horse requires about four years to reach maturity, a mare gestates a foal in eleven months and can go into heat almost immediately thereafter. By contrast, elephants reach adulthood after seventeen years, take 18-22 months to gestate and female elephants do not typically mate until their calf is weaned, four to five years after its birth. A ruler looking to build a stable of cavalry horses thus may start small and grow rapidly; a ruler looking to build a corps of war elephants is looking at a very slow process. This is compounded by the fact that elephants are notoriously difficult to breed in captivity. There is some speculation that the Seleucids nonetheless attempted this at Apamea, where they based their elephants – in any event, they seem to have remained dependent on imported Indian elephants to maintain the elephant corps. If a self-sustaining elephant breeding program for war elephants was ever created, we do not know about it.

To make matters worse, elephants require massive amounts of food and water. In video-games, this is often represented through a high elephant “upkeep” cost – but this often falls well short of the reality of keeping these animals for war. Let’s take Total War: Rome II as an example: a unit of Roman (auxiliary) African elephants (12 animals), costs 180 upkeep, compared to 90 to 110 upkeep for 80 horses of auxiliary cavalry (there are quite a few types) – so one elephant (with a mahout) costs 15 upkeep against around 1.25 for a horse and rider (a 12:1 ratio). Paradox’s Imperator does something similar, with a single unit of war elephants requiring 1.08 upkeep, compared to just 0.32 for light cavalry; along with this, elephants have a heavy “supply weight” – twice that of an equivalent number of cavalry (so something like a 2:1 or 3:1 ratio of cost).

Believe it or not, this understates just how hungry – and expensive – elephants are. The standard barley ration for a Roman horse was 7kg of barley per day (7 Attic medimnoi per month; Plb. 6.39.12); this would be supplemented by grazing. Estimates for the food requirements of elephants vary widely (in part, it is hard to measure the dietary needs of grazing animals), but elephants require in excess of 1.5% of their body-weight in food per day. Estimates for the dietary requirements of the Asian elephant can range from 135 to 300kg per day in a mix of grazing and fodder – and remember, the preference in war elephants is for large, mature adult males, meaning that most war elephants will be towards the top of this range. Accounting for some grazing (probably significantly less than half of dietary needs) a large adult male elephant is thus likely to need something like 15 to 30 times the food to sustain itself as a stable-fed horse.

In peacetime, these elephants have to be fed and maintained, but on campaign the difficulty of supplying these elephants on the march is layered on top of that. We’ve discussed elsewhere the difficulty in supplying an army with food, but large groups of elephants magnify this problem immensely. The 54 elephants the Seleucids brought to Magnesia might have consumed as much food as 1,000 cavalrymen (that’s a rider, a horse and a servant to tend that horse and its rider).

But that still understates the cost intensity of elephants. Bringing a horse to battle in the ancient world required the horse, a rider and typically a servant (this is neatly implied by the more generous rations to cavalrymen, who would be expected to have a servant to be the horse’s groom, unlike the poorer infantry, see Plb. above). But getting a war elephant to battle was a team effort. Trautmann (2015) notes that elephant stables required riders, drivers, guards, trainers, cooks, feeders, guards, attendants, doctors and specialist foot-chainers (along with specialist hunters to capture the elephants in the first place!). Many of these men were highly trained specialists and thus had to be quite well paid.

Now – and this is important – pre-modern states are not building their militaries from the ground up. What they have is a package of legacy systems. In Rome’s case, the defeat of Carthage in the Second Punic War resulted in Rome having North African allies who already had elephants. Rome could accept those elephant allied troops, or say “no” and probably get nothing to replace them. In that case – if the choice is between “elephants or nothing” – then you take the elephants. What is telling is that – as Rome was able to exert more control over how these regions were exploited – the elephants vanished, presumably as the Romans dismantled or neglected the systems for capturing and training them (which they now controlled directly).

That resolves part of our puzzle: why did the Romans use elephants in the second and early first centuries B.C.? Because they had allies whose own military systems involved elephants. But that leaves the second part of the puzzle – Rome doesn’t simply fail to build an elephant program. Rome absorbs an elephant program and then lets it die. Why?

For states with scarce resources – and all states have scarce resources – using elephants meant not directing those resources (food, money, personnel, time and administrative capacity) for something else. If the elephant had no other value (we’ll look at one other use next week), then developing elephants becomes a simple, if difficult, calculation: are the elephants more likely to win the battle for me than the equivalent resources spent on something else, like cavalry. As we’ve seen above, that boils down to comparisons between having just dozens of elephants or potentially hundreds or thousands of cavalry.

The Romans obviously made the bet that investing in cavalry or infantry was a better use of time, money and resources than investing in elephants, because they thought elephants were unlikely to win battles. Given Rome’s subsequent spectacular battlefield success, it is hard to avoid the conclusion they were right, at least in the Mediterranean context.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: War Elephants, Part II: Elephants against Wolves”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2019-08-02.

February 6, 2024

QotD: Sparta’s actually mediocre military performance

Sparta was one of the largest Greek city-states in the classical period, yet it struggled to achieve meaningful political objectives; the result of Spartan arms abroad was mostly failure. Sparta was particularly poor at logistics; while Athens could maintain armies across the Eastern Mediterranean, Sparta repeatedly struggled to keep an army in the field even within Greece. Indeed, Sparta spent the entirety of the initial phase of the Peloponnesian War, the Archidamian War (431-421 B.C.), failing to solve the basic logistical problem of operating long term in Attica, less than 150 miles overland from Sparta and just a few days on foot from the nearest friendly major port and market, Corinth.

The Spartans were at best tactically and strategically uncreative. Tactically, Sparta employed the phalanx, a close-order shield and spear formation. But while elements of the hoplite phalanx are often presented in popular culture as uniquely Spartan, the formation and its equipment were common among the Greeks from at least the early fifth century, if not earlier. And beyond the phalanx, the Spartans were not innovators, slow to experiment with new tactics, combined arms, and naval operations. Instead, Spartan leaders consistently tried to solve their military problems with pitched hoplite battles. Spartan efforts to compel friendship by hoplite battle were particularly unsuccessful, as with the failed Spartan efforts to compel Corinth to rejoin the Spartan-led Peloponnesian League by force during the Corinthian War.

Sparta’s military mediocrity seems inexplicable given the city-state’s popular reputation as a highly militarized society, but modern scholarship has shown that this, too, is mostly a mirage. The agoge, Sparta’s rearing system for citizen boys, frequently represented in popular culture as akin to an intense military bootcamp, in fact included no arms training or military drills and was primarily designed to instill obedience and conformity rather than skill at arms or tactics. In order to instill that obedience, the older boys were encouraged to police the younger boys with violence, with the result that even in adulthood Spartan citizens were liable to settle disputes with their fists, a tendency that predictably made them poor diplomats.

Bret Devereaux, “Spartans Were Losers”, Foreign Policy, 2023-07/22.

January 31, 2024

QotD: The inner-most “zones” outside a typical pre-modern city

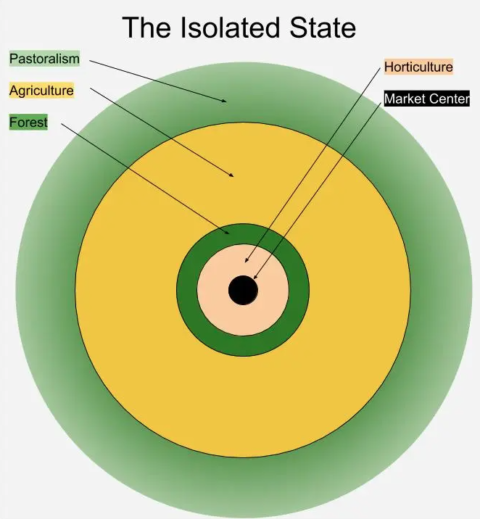

Diagram of von Thünen’s model from The Isolated State, after Morley (1996), 62. The agriculture ring is subdivided by intensity (intensive, long-lay and three-field), but here I have merged them for simplicity. The agriculture zone is wider because it did, in fact, tend to cover a larger area. The fade in the pastoralism zone is meant to indicate shifts from ranching to transhumance.

We’ll start at the inside, right next to the city and move outward. Imagine each “zone” as a wider concentric circle, moving outward from the city (see the image to the right). Because transportation costs (especially overland) are so high, distance from the city plays a dominant role in how the land is used and thus consequently what the countryside around the city looks like. As you move further and further away, transportation costs interact with the structure of agriculture to make different activities make more sense, creating somewhat predictable patterns.

Land very close to the city is valuable because its produce can reach the market with much lower transportation costs (and pretty much always in a single day’s walk). As a result, if the land can support any kind of productive use, it will not be left empty. Instead, the land is going to be put to the most productive use possible. Improvements that – because of cost or labor – might not be attempted on less valuable land further out will likely be done in close proximity to the city. Stepping out of our ideal model for a moment: this is especially true of irrigation, since cities tend to be on waterways (especially rivers) anyway, making irrigation both more valuable due to low transport costs and easier to accomplish.

Thus land in this innermost zone is likely to be heavily improved (irrigation, terracing to get maximum space out of hills, etc). Labor use will also be intensive, both because it is readily available (you are right next to the major population center) and because labor costs are small compared to the high value of the land. If you have managed to get some farmland right outside the city gates, it is very much worth your time to hire whatever labor you need to get the most out of it, so as to recoup the cost of buying or holding such valuable land.

The other improvement one is likely to do in this zone, at least for growing crops, is make extensive use of fertilizer, which in this case generally means manure. The good news is that this zone is directly next to the city, with its intense concentration of animals and people producing manure, making manure cheaper (yes, people did pay for it). Extensive use of manure lets the fields stay under cultivation more often – being fallowed less frequently. At greater distance, the cost of the manure for this begins to outweigh the value of the extra crops, but so close to the city, land this valuable ought to be kept producing as much as possible.

So what kinds of land use does this lead to? The two key activities that von Thünen identifies are horticulture and dairying, to which I’ll add trough-fed animals like pigs (not quite dairy, but as we’ll see, similar from an economic perspective). Why? Horticulture – the intensive growing of fruits and vegetables, often in small “market gardens” – is labor intensive and offers a high economic yield for the space. Land used for horticulture can be kept under almost continual cultivation (if manured, but see above), but gardens can be fussy and demand quite a lot of labor, compared to hardier plants (like maize corn or wheat). Likewise, dairy animals (which, up close to a large city, will be stall-fed rather than grazed or else transported in “on the hoof” and grazed much further out) and pigs (fed by trough) don’t require much space and offer a high economic yield. Both also produce manure which is in demand near the city for the reasons described above.

The other reason to keep these activities so close to the city is access to the market, for two related reasons. First, fresh dairy products, meats and vegetables spoil rapidly, so they must be gotten to market quickly. Remember that this is a world without refrigeration, so as soon as the plant is picked, the cow is milked or the pig is killed, the clock is ticking on spoilage (yes, there are ways to preserve meat, of course – but we’re talking fresh animal products). Precisely because these foods don’t travel or keep well, they tend to be luxury products as well – something produced for the market and bought by rich non-farmers who live in the city.

So what kind of terrain should we see here? Not open grassland or nice wide open fields. Instead, expect small plots, with clustered buildings, typically clinging to the roads leading into the city. Now – especially in the post-gunpowder age – there might be laws forbidding certain kinds of structures close to the city walls (if the city is walled), which might create some open space (but typically not vast). Likewise, when looking at historical city maps, also be wary: this innermost land-use zone was often contained within the city walls of smaller cities.

The next zone – also quite close to the city in von Thünen’s model is – perhaps somewhat surprisingly – a forest zone. That’s not to say that this is generally wild, uncontrolled forest. The reason for a forest zone at such close distance to the city is to provide wood, particularly firewood for heating. Trees might be arranged intentionally along field separations or on spots of agriculturally marginal land close to the city. Forests like these in the Middle Ages would often have been coppiced or pollarded – that is, the trees would have been intentionally cut to produce lots of long, thin straight branches which can be easily harvested to produce nice, evenly sized bits of wood.

Wood is obviously at no risk of spoiling, but it is heavy and bulky, making a close supply valuable. Moreover, the city will need quite a lot of it, for cooking and heating. That said, trees can often be grown either on very marginal (for agriculture) land or else between fields and farms outside of the city, so these patches of forest might often go on land that is a touch too rough or poor for intensive agriculture, or otherwise be squeezed in between land used for other purposes. Still, it is quite common to find spots of forest next to cities and villages alike.

(To answer a quibble in advance: of course this assumes wood is a key heating element. Societies in more arid climates often lack sufficient wood and might use dung, while wet enough areas may use peat. Historically, London shifted over to using mineral coal earlier than most places. All of these choices will impact the role and importance of forest near the city.)

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: The Lonely City, Part I: The Ideal City”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2019-07-12.

January 26, 2024

QotD: How an oath worked in pre-modern cultures

You swear an oath because your own word isn’t good enough, either because no one trusts you, or because the matter is so serious that the extra assurance is required.

That assurance comes from the presumption that the oath will be enforced by the divine third party. The god is called – literally – to witness the oath and to lay down the appropriate curses if the oath is violated. Knowing that horrible divine punishment awaits forswearing, the oath-taker, it is assumed, is less likely to make the oath. Interestingly, in the literature of classical antiquity, it was also fairly common for the gods to prevent the swearing of false oaths – characters would find themselves incapable of pronouncing the words or swearing the oath properly.

And that brings us to a second, crucial point – these are legalistic proceedings, in the sense that getting the details right matters a great deal. The god is going to enforce the oath based on its exact wording (what you said, not what you meant to say!), so the exact wording must be correct. It was very, very common to add that oaths were sworn “without guile or deceit” or some such formulation, precisely to head off this potential trick (this is also, interestingly, true of ancient votives – a Roman or a Greek really could try to bargain with a god, “I’ll give X if you give Y, but only if I get by Z date, in ABC form.” – but that’s vows, and we’re talking oaths).

Thus for instance, runs an oath of homage from the Chronicle of the Death of Charles the Good from 1127:

“I promise on my faith that I will in future be faithful to count William, and will observe my homage to him completely against all persons in good faith and without deceit.”

Not all oaths are made in full, with the entire formal structure, of course. Short forms are made. In Greek, it was common to transform a statement into an oath by adding something like τὸν Δία (by Zeus!). Those sorts of phrases could serve to make a compact oath – e.g. μὰ τὸν Δία! (yes, [I swear] by Zeus!) as an answer to the question is essentially swearing to the answer – grammatically speaking, the verb of swearing is necessary, but left implied. We do the same thing, (“I’ll get up this hill, by God!”). And, I should note, exactly like in English, these forms became standard exclamations, as in Latin comedy, this is often hercule! (by Hercules!), edepol! (by Pollux!) or ecastor! (By Castor! – oddly only used by women). One wonders in these cases if Plautus chooses semi-divine heroes rather than full on gods to lessen the intensity of the exclamation (“shoot!” rather than “shit!” as it were). Aristophanes, writing in Greek, has no such compunction, and uses “by Zeus!” quite a bit, often quite frivolously.

Nevertheless, serious oaths are generally made in full, often in quite specific and formal language. Remember that an oath is essentially a contract, cosigned by a god – when you are dealing with that kind of power, you absolutely want to be sure you have dotted all of the “i”‘s and crossed all of the “t”‘s. Most pre-modern religions are very concerned with what we sometimes call “orthopraxy” (“right practice” – compare orthodoxy, “right doctrine”). Intent doesn’t matter nearly as much as getting the exact form or the ritual precisely correct (for comparison, ancient paganisms tend to care almost exclusively about orthopraxy, whereas medieval Christianity balances concern between orthodoxy and orthopraxy (but with orthodoxy being the more important)).

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Oaths! How do they Work?”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2019-06-28.

January 22, 2024

QotD: Mao’s theory of “protracted war” as adapted to Vietnamese conditions by Võ Nguyên Giáp

The primary architect of Vietnam’s strategy, initially against French colonial forces and then later against the United States and the US-backed South Vietnamese (Republic of Vietnam or RVN) government was Võ Nguyên Giáp.

Giáp was facing a different set of challenges in Vietnam facing either France or the United States which required the framework of protracted war to be modified. First, it must have been immediately apparent that it would never be possible for a Vietnamese-based army to match the conventional military capability of its enemies, pound-for-pound. Mao could imagine that at some point the Red Army would be able to win an all-out, head-on-head fight with the Nationalists, but the gap between French and American capabilities and Vietnamese Communist capabilities was so much wider.

At the same time, trading space for time wasn’t going to be much of an option either. China, of course, is a very large country, with many regions that are both vast, difficult to move in, and sparsely populated. It was thus possible for Mao to have his bases in places where Nationalist armies literally could not reach. That was never going to be possible in Vietnam, a country in which almost the entire landmass is within 200 miles of the coast (most of it is far, far less than that) and which is about 4% the size of China.

So the theory is going to have to be adjusted, but the basic groundwork – protract the war, focus on will rather than firepower, grind your enemy down slowly and proceed in phases – remains.

I’m going to need to simplify here, but Giáp makes several key alterations to Mao’s model of protracted war. First, even more than Mao, the political element in the struggle was emphasized as part of the strategy, raised to equality as a concern with the military side and fused with the military operation; together they were termed dau tranh, roughly “the struggle”. Those political activities were divided into three main components. Action among one’s own people consisted of propaganda and motivation designed to reinforce the will of the populace that supported the effort and to gain recruits. Then, action among the enemy people – here meaning Vietnamese who were under the control of the French colonial government or South Vietnam and not yet recruited into the struggle – a mix of propaganda and violent action to gain converts and create dissension. Finally, action against the enemy military, which consisted of what we might define as terroristic violence used as message-sending to negatively impact enemy morale and to encourage Vietnamese who supported the opposition to stop doing so for their own safety.

Part of the reason the political element of this strategy was so important was that Giáp knew that casualty ratios, especially among guerrilla forces – on which, as we’ll see, Giáp would have to rely more heavily – would be very unfavorable. Thus effective recruitment and strong support among the populace was essential not merely to conceal guerrilla forces but also to replace the expected severe losses that came with fighting at such a dramatic disadvantage in industrial firepower.

That concern in turn shaped force-structure. Giáp theorized an essentially three-tier system of force structure. At the bottom were the “popular troops”, essentially politically agitated peasants. Lightly armed, minimally trained but with a lot of local knowledge about enemy dispositions, who exactly supports the enemy and the local terrain, these troops could both accomplish a lot of the political objectives and provide information as well as functioning as local guerrillas in their own villages. Casualties among popular troops were expected to be high as they were likely to “absorb” reprisals from the enemy for guerrilla actions. Experienced veterans of these popular troops could then be recruited up into the “regional troops”, trained men who could now be deployed away from their home villages as full-time guerrillas, and in larger groups. While popular troops were expected to take heavy casualties, regional troops were carefully husbanded for important operations or used to organize new units of popular troops. Collectively these two groups are what are often known in the United States as the Viet Cong, though historians tend to prefer their own name for themselves, the National Liberation Front (Mặt trận Dân tộc Giải phóng miền Nam Việt Nam, “National Liberation Front for South Vietnam”) or NLF. Finally, once the French were forced to leave and Giáp had a territorial base he could operate from in North Vietnam, there were conventional forces, the regular army – the People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) – which would build up and wait for that third-phase transition to conventional warfare.

The greater focus on the structure of courses operating in enemy territory reflected Giáp’s adjustment of how the first phase of the protracted war would be fought. Since he had no mountain bases to fall back to, the first phase relied much more on political operations in territory controlled by the enemy and guerrilla operations, once again using the local supportive population as the cover to allow guerrillas and political agitators (generally the same folks, cadres drawn from the regional troops to organize more popular troops) to move undetected. Guerrilla operations would compel the less-casualty-tolerant enemy to concentrate their forces out of a desire for force preservation, creating the second phase strategic stalemate and also clearing territory in which larger mobile forces could be brought together to engage in mobile warfare, eventually culminating in a shift in the third phase to conventional warfare using the regional and regular troops.

Finally, unlike Mao, who could envision (and achieve) a situation where he pushed the Nationalists out of the territories they used to recruit and supply their armies, the Vietnamese Communists had no hope (or desire) to directly attack France or the United States. Indeed, doing so would have been wildly counter-productive as it likely would have fortified French or American will to continue the conflict.

That limitation would, however, demand substantial flexibility in how the Vietnamese Communists moved through the three phases of protracted war. This was not something realized ahead of time, but something learned through painful lessons. Leadership in the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV = North Vietnam) was a lot more split than among Mao’s post-Long-March Chinese Communist Party; another important figure, Lê Duẩn, who became general secretary in 1960, advocated for a strategy of “general offensive” paired with a “general uprising” – essentially jumping straight to the third phase. The effort to implement that strategy in 1964 nearly overran the South, with ARVN (Army of the Republic of Vietnam – the army of South Vietnam) being defeated by PAVN and NLF forces at the Battles of Bình Giã and Đồng Xoài (Dec. 1964 and June 1965, respectively), but this served to bring the United States more fully into the war – a tactical and operational victory that produced a massive strategic setback.

Lê Duẩn did it again in 1968 with the Tet Offensive, attempting a general uprising which, in an operational sense, mostly served to reveal NLF and PAVN formations, exposing them to US and ARVN firepower and thus to severe casualties, though politically and thus strategically the offensive ended up being a success because it undermined American will to continue the fight. American leaders had told the American public that the DRV and the NLF were largely defeated, broken forces – the sudden show of strength exposed those statements as lies, degrading support at home. Nevertheless, in the immediate term, the Tet Offensive’s failure on the ground nearly destroyed the NLF and forced the DRV to back down the phase-ladder to recover. Lê Duẩn actually did it again in 1972 with the Eastern Offensive when American ground troops were effectively gone, exposing his forces to American airpower and getting smashed up for his troubles.

It is difficult to see Lê Duẩn’s strategic impatience as much more than a series of blunders – but crucially Giáp’s framework allowed for recovery from these sorts of defeats. In each case, the NLF and PAVN forces were compelled to do something Mao’s model hadn’t really envisaged, which was to transition back down the phase system, dropping back to phase II or even phase I in response to failed transitions to phase III. By moving more flexibly between the phases (while retaining a focus on the conditions of eventual strategic victory), the DRV could recover from such blunders. I think Wayne Lee actually puts it quite well that whereas Mao’s plan relied on “many small victories” adding up to a large victory (without the quick decision of a single large victory), Giáp’s more flexible framework could survive many small defeats on the road to an eventual strategic victory when the will of the enemy to continue the conflict was exhausted.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: How the Weak Can Win – A Primer on Protracted War”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2022-03-03.

January 17, 2024

QotD: Did Hari Seldon live in vain?

Both cliodynamics and psychohistory assume these differences and problems “come out in the wash” over a long enough period and a big enough sample. It doesn’t take much of a counterfactual thought experiment about how small changes by individuals could lead to enormous historical differences to see that they don’t. The defense that cliodynamics only deals in probabilities is little comfort here: in fact the apparent randomness (which one may argue is merely complexity on a scale that is beyond simulation) swallows the patterns. One could easily argue, for instance, that the extremely unlikely career of our fellow Temujin is a necessary cause (albeit merely one of many, several of which might be considered deeply improbable) for the fact that all commercial pilots and air traffic controllers worldwide have to learn a form of English (which one may well assume has its own structural knock-on effects in terms of the language used for business and from there the outsized cultural impact of English-speaking countries).1 No one in 1158 was likely to have supposed that English – a language at that time not even spoken by the English nobility (they spoke French)! – would become the first truly global lingua franca (and arguably the only one, though here caveats may overwhelm the claim) and thus the language of aviation. But that is precisely the kind of big structural change that is going to be really impactful on all sorts of other questions, like patterns of commerce, wealth, culture and influence.

Such complex causation defies general laws (even before we get into the fact that humans also observe history, which creates even more complexity) with such tremendous import from such unlikely events in an experiment which can only be run once without a control.

The other problem is evidence. Attempting to actually diagnose and model societies like this demands a lot of the data and not merely that you need a lot of it. You need consistent data which projects very far back in history which is accurate and fairly complete, so that it can be effectively compared. Trying, for instance, to compare ancient population estimates, which often have error bars of 100% or more, with modern, far more precise population estimates is bound to cause some real problems in teasing out clear correlations in data. The assumptions you make in tuning those ancient population figures can and will swallow any conclusions you might draw from the comparison with modern figures beyond the fairly obvious (there are more people now). But even the strongest administrative states now have tremendous difficulty getting good data on their own lower classes! Much of the “data” we think we have are themselves statistical estimates. The situation even in the very recent past is much worse and only degrades from there as one goes further back!

By way of example, I was stunned that Turchin figures he can identify “elite overproduction” and quantify wealth concentration into the deep past, including into the ancient world (Romans, late Bronze Age, etc). I study the Romans; their empire is only 2,000 years ago and moreover probably the single best-attested ancient society apart from perhaps Egypt or China (and even then I think Rome comes out quite solidly ahead). And even in that context, our estimates for the population of Roman Italy range from c. 5m to three to four times that much. Estimates for the size of the Roman budget under Augustus or Tiberius (again, by far the best attested period we have) range wildly (though within an order of magnitude, perhaps around 800 million sestertii). Even establishing a baseline for this society with the kind of precision that might let you measure important but modest increases in the size of the elite is functionally impossible with such limited data.

When it comes to elites, we have at best only one historical datapoint for the size of the top Roman census class (the ordo equester) and it’s in 225 BC, but as reported by Polybius in the 140s and also he may have done the math wrong and it also isn’t clear if he’s actually captured the size of the census class! We know in the imperial period what the minimum wealth requirement to be in the Senate was, but we don’t know what the average wealth of a senator was (we tend to hopefully assume that Pliny the Younger is broadly typically, but he might not have been!), nor do we know the size of the senatorial class itself (formed as a distinct class only in the empire), nor do we know how many households there were of senatorial wealth but which didn’t serve in the Senate because their members opted not to run for public office. One can, of course, make educated guesses for these things (it is often useful and important to do so), but they are estimates founded on guesses supported by suppositions; a castle of sand balanced atop other castles of sand. We can say with some confidence that the Late Roman Republic and the Early Roman Empire saw tremendous concentrations of wealth; can we quantity that with much accuracy? No, not really; we can make very rough estimates, but these are at the mercy of their simplifying assumptions.

And this is, to be clear, the very best attested ancient society and only about 2,000 years old at that. The data situation for other ancient societies can only be worse – unless, unless one begins by assuming elite overproduction is a general feature of complex, wealthy societies and then reads that conclusion backwards into what little data exists. But that isn’t historical research; it is merely elevating confirmation bias to a research methodology.

As noted, I have other nitpicks – particularly the tendency to present very old ideas as new discoveries, like secular cycles (Polybius, late 2nd century BC) or war as the foundation of complex societies (Heraclitus, d. c. 475 BC) without always seeming to appreciate just how old and how frequently recurring the idea is (such that it might, for instance, be the sort of intuitive idea many people might independently come up with, even if it was untrue or that it might be the kind of idea that historians had considered long ago and largely rejected for well established reasons) – but this will, I hope, suffice for a basic explanation of why I find the idea of this approach unsatisfying. This is, to be clear, not a rejection of the role of data or statistics in history, both of which can be tremendously important. Nor is it a rejection of the possible contributions of non-historians (who have important contributions to make), though I would ask that someone wading into the field familiarize themselves with it (perhaps by doing some traditional historical research), before declaring they had revolutionized the field. Rather it is an argument both that these things cannot replace more traditional historical methods and also that their employment, like the employment of any historical method, must come with a very strong dose of epistemic humility.

Psychohistory only works in science fiction where the author, as the god of his universe, can make it work. Today’s psychohistorians have no such power.

Bret Devereaux, “Fireside Friday: October 15, 2021”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-10-15.

1. For those confused by the causation, the Mongols are considered the most likely vector for the transmission of gunpowder from China, where it was invented, to Europe. Needless to say, having a single polity spanning the entire Eurasian Steppe at the precise historical moment for this to occur sure seems like a low probability event! In any event, European mastery of gunpowder led directly into European naval dominance in the world’s oceans (its impact on land warfare dominance is much more complex) which in turn led to European dominance at sea. At the same time, the English emphasis on gunnery over boarding actions early in this period (gunpowder again) provided a key advantage which contributed to subsequent British naval dominance among European powers (and also the British navy’s “cult of gunnery” in evidence to the World Wars at least), which in turn allowed for the wide diffusion of English as a business and trade language. In turn, American and British prominence in the post-WWII global order made English the natural language for NATO and thus the ICAO convention that English be used universally for all aircraft communication.

January 12, 2024

QotD: Rome’s Italic “allies”

The Roman Republic spent its first two and a half centuries (or so) expanding fitfully through peninsular Italy (that is, Italy south of the Po River Valley, not including Sicily). This isn’t the place for a full discussion of the slow process of expanding Roman control (which wouldn’t be entirely completed until 272 with the surrender of Tarentum). The consensus position on the process is that it was one in which Rome exploited local rivalries to champion one side or the other making an ally of the one by intervening and the other by defeating and subjecting them (this view underlies the excellent M.P. Fronda, Between Rome and Carthage: Southern Italy During the Second Punic War (2010); E.T. Salmon, The Making of Roman Italy (1982) remains a valuable introduction to the topic). More recently, N. Terranato, The Early Roman Expansion into Italy (2019) has argued for something more based on horizontal elite networks and diplomacy, though this remains decidedly a minority opinion (I myself am rather closer to the consensus position, though Terranato has a point about the role of elite negotiation in the process).

The simple (and perhaps now increasingly dated) way I explain this to my students is that Rome follows the Goku Model of Imperialism: I beat you, therefore we are now friends. Defeated communities in Italy (the system is different outside of Italy) are made to join Rome’s alliance network as socii (“allies”), do not have tribute imposed on them, but must supply their soldiers to fight with Rome when Rome is at war, which is always.

It actually doesn’t matter for us how this expansion was accomplished; rather we’re interested in the sort of order the Romans set up when they did expand. The basic blueprint for how Rome interacted with the Italians may have emerged as early as 493 with the Foedus Cassianum, a peace treaty which ended a war between Rome and [the] Latin League (an alliance of ethnically Latin cities in Latium). To simplify quite a lot, the Roman “deal” with the communities of Italy which one by one came under Roman power went as follows:

- All subject communities in Italy became socii (“allies”). This was true if Rome actually intervened to help you as your ally, or if Rome intervened against you and conquered your community.

- The socii retained substantial internal autonomy (they kept their own laws, religions, language and customs), but could have no foreign policy except their alliance with Rome.

- Whenever Rome went to war, the socii were required to send soldiers to assist Rome’s armies; the number of socii in Rome’s armies ranged from around half to perhaps as much as two thirds at some points (though the socii outnumbered the Romans in Italy about 3-to-1 in 225, so the Romans made more strenuous manpower demands on themselves than their allies).

- Rome didn’t impose tribute on the socii, though the socii bore the cost of raising and paying their detachments of troops in war (except for food, which the Romans paid for, Plb. 6.39.14).

- Rome goes to war every year.

- No, seriously. Every. Year. From 509 to 31BC, the only exception was 241-235. That’s it. Six years of peace in 478 years of republic. The socii do not seem to have minded very much; they seem to have generally been as bellicose as the Romans and anyway …

- The spoils of Roman victory were split between Rome and the socii. Consequently, as one scholar memorably put it, the Roman alliance was akin to, “a criminal operation which compensates its victims by enrolling them in the gang and inviting them to share to proceeds of future robberies” (T. Cornell, The Beginnings of Rome (1995)).

- The alliance system included a ladder of potential relationships with Rome which the Romans might offer to loyal allies.