Now I should note that the initial response in Italy to the shocking appearance of effective siege artillery was not to immediately devise an almost entirely new system of fortifications from first principles, but rather – as you might imagine – to hastily retrofit old fortresses. But […] we’re going to focus on the eventual new system of fortresses which emerge, with the first mature examples appearing around the first decades of the 1500s in Italy. This system of European gunpowder fort that spreads throughout much of Europe and into the by-this-point expanding European imperial holdings abroad (albeit more unevenly there) goes by a few names: “bastion” fort (functional, for reasons we’ll get to in a moment), “star fort” (marvelously descriptive), and the trace italienne or “the Italian line”. since that was where it was from.

Since the goal remains preventing an enemy from entering a place, be that a city or a fortress, the first step has to be to develop a wall that can’t simply be demolished by artillery in a good afternoon or two. The solution that is come upon ends up looking a lot like those Chinese rammed earth walls: earthworks are very good at absorbing the impact of cannon balls (which, remember, are at this point just that: stone and metal balls; they do not explode yet): small air pockets absorb some of the energy of impact and dirt doesn’t shatter, it just displaces (and not very far: again, no high explosive shells, so nothing to blow up the earthwork). Facing an earthwork mound with stonework lets the earth absorb the impacts while giving your wall a good, climb-resistant face.

So you have your form: a stonework or brick-faced wall that is backed up by essentially a thick earthen berm like the Roman agger. Now you want to make sure incoming cannon balls aren’t striking it dead on: you want to literally play the angles. Inclining the wall slightly makes its construction easier and the end result more stable (because earthworks tend not to stand straight up) and gives you an non-perpendicular angle of impact from cannon when they’re firing at very short range (and thus at very low trajectory), which is when they are most dangerous since that’s when they’ll have the most energy in impact. Ideally, you’ll want more angles than this, but we’ll get to that in a moment.

Because we now have a problem: escalade. Remember escalade?

Earthworks need to be wide at the base to support a meaningful amount of height, tall-and-thin isn’t an option. Which means that in building these cannon resistant walls, for a given amount of labor and resources and a given wall circuit, we’re going to end up with substantially lower walls. We can enhance their relative height with a ditch several out in front (and we will), but that doesn’t change the fact that our walls are lower and also that they now incline backwards slightly, which makes them easier to scale or get ladders on. But obviously we can’t achieved much if we’ve rendered our walls safe from bombardment only to have them taken by escalade. We need some way to stop people just climbing over the wall.

The solution here is firepower. Whereas a castle was designed under the assumption the enemy would reach the foot of the wall (and then have their escalade defeated), if our defenders can develop enough fire, both against approaching enemies and also against any enemy that reaches the wall, they can prohibit escalade. And good news: gunpowder has, by this point, delivered much more lethal anti-personnel weapons, in the form of lighter cannon but also in the form of muskets and arquebuses. At close range, those weapons were powerful enough to defeat any shield or armor a man could carry, meaning that enemies at close range trying to approach the wall, set up ladders and scale would be extremely vulnerable: in practice, if you could get enough muskets and small cannon firing at them, they wouldn’t even be able to make the attempt.

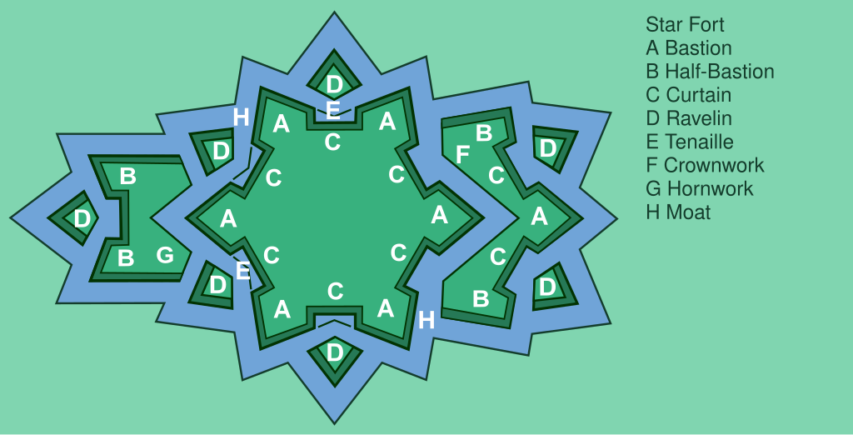

But the old projecting tower of the castle, you will recall, was designed to allow only a handful of defenders fire down any given section of wall; we still want that good enfilade fire effect, but we need a lot more space to get enough muskets up there to develop that fire. The solution: the bastion. A bastion was an often diamond or triangular-shaped projection from the wall of the fort, which provided a longer stretch of protected wall which could fire down the length of the curtain wall. It consists of two “flanks” which meet the curtain wall and are perpendicular to it, allowing fire along the wall; the “faces” (also two) then face outward, away from the fort to direct fire at distant besiegers. When places at the corners of forts, this setup tends to produce outward-spiked diamonds, while a bastion set along a flat face of curtain wall tends to resemble an irregular pentagon (“home plate”) shape [Wiki]. The added benefit for these angles? From the enemy siege lines, they present an oblique profile to enemy artillery, making the bastions quite hard to batter down with cannon, since shots will tend to ricochet off of the slanted line.

In the simplest trace italienne forts [Wiki], this is all you will need: four or five thick-and-low curtain walls to make the shape, plus a bastion at each corner (also thick-and-low, sometimes hollow, sometimes all at the height of the wall-walk), with a dry moat (read: big ditch) running the perimeter to slow down attackers, increase the effective height of the wall and shield the base of the curtain wall from artillery fire.

But why stay simple, there’s so much more we can do! First of all, our enemy, we assume, have cannon. Probably lots of cannon. And while our walls are now cannon resistant, they’re not cannon immune; pound on them long enough and there will be a breach. Of course collapsing a bastion is both hard (because it is angled) and doesn’t produce a breach, but the curtain walls both have to run perpendicular to the enemy’s firing position (because they have to enclose something) and if breached will allow access to the fort. We have to protect them! Of course one option is to protect them with fire, which is why our bastions have faces; note above how while the flanks of the bastions are designed for small arms, the faces are built with cannon in mind: this is for counter-battery fire against a besieger, to silence his cannon and protect the curtain wall. But our besieger wouldn’t be here if they didn’t think they could decisively outshoot our defensive guns.

But we can protect the curtain further, and further complicate the attack with outworks [Wiki], effectively little mini-bastions projecting off of the main wall which both provide advanced firing positions (which do not provide access to the fort and so which can be safely abandoned if necessary) and physically obstruct the curtain wall itself from enemy fire. The most basic of these was a ravelin (also called a “demi-lune”), which was essentially a “flying” bastion – a triangular earthwork set out from the walls. Ravelins are almost always hollow (that is, the walls only face away from the fort), so that if attackers were to seize a ravelin, they’d have no cover from fire coming from the main bastions and the curtain wall.

And now, unlike the Modern Major-General, you know what is meant by a ravelin … but are you still, in matters vegetable, animal and mineral, the very model of a modern Major-General?

But we can take this even further (can you tell I just love these damn forts?). A big part of our defense is developing fire from our bastions with our own cannon to force back enemy artillery. But our bastions are potentially vulnerable themselves; our ravelins cover their flanks, but the bastion faces could be battered down. We need some way to prevent the enemy from aiming effective fire at the base of our bastion. The solution? A crownwork. Essentially a super-ravelin, the crownwork contains a full bastion at its center (but lower than our main bastion, so we can fire over it), along with two half-bastions (called, wait for it, “demi-bastions”) to provide a ton of enfilade fire along the curtain wall, physically shielding our bastion from fire and giving us a forward fighting position we can use to protect our big guns up in the bastion. A smaller version of the crownwork, called a hornwork can also be used: this is just the two half-bastions with the full bastion removed, often used to shield ravelins (so you have a hornwork shielding a ravelin shielding the curtain wall shielding the fort). For good measure, we can connect these outworks to the main fort with removable little wooden bridges so we can easily move from the main fort out to the outworks, but if the enemy takes an outwork, we can quickly cut it off and – because the outworks are all made hollow – shoot down the attackers who cannot take cover within the hollow shape.

An ideal form of a bastion fortress to show each kind of common work and outwork.

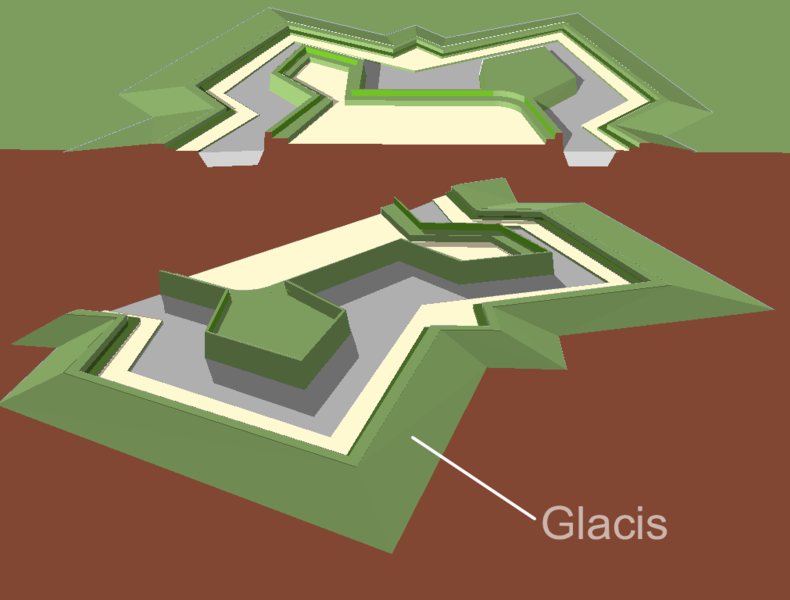

Drawing by Francis Lima via Wikimedia Commons.We can also do some work with the moat. By adding an earthwork directly in front of it, which arcs slightly uphill, called a glacis, we can both put the enemy at an angle where shots from our wall will run parallel to the ground, thus exposing the attackers further as they advance, and create a position for our own troops to come out of the fort and fire from further forward, by having them crouch in the moat behind the glacis. Indeed, having prepared, covered forward positions (which are designed to be entirely open to the fort) for firing from at defenders is extremely handy, so we could even put such firing positions – set up in these same, carefully mathematically calculated angle shapes, but much lower to the ground – out in front of the glacis; these get all sorts of names: a counterguard or couvreface if they’re a simple triangle-shape, a redan if they have something closer to a shallow bastion shape, and a flèche if they have a sharper, more pronounced face. Thus as an enemy advances, defending skirmishers can first fire from the redans and flèches, before falling back to fire from the glacis while the main garrison fires over their heads into the enemy from the bastions and outworks themselves.

A diagram showing a glacis supporting a pair of bastions, one hollow, one not.

Diagram by Arch via Wikimedia Commons.At the same time, a bastion fortress complex might connect multiple complete circuits. In some cases, an entire bastion fort might be placed within the first, merely elevated above it (the term for this is a “cavalier“) so that both could fire, one over the other. Alternately, when entire cities were enclosed in these fortification systems (and that was common along the fracture zones between the emerging European great powers), something as large as a city might require an extensive fortress system, with bastions and outworks running the whole perimeter of the city, sometimes with nearly complete bastion fortresses placed within the network as citadels.

Fort Saint-Nicolas, which dominates the Old Port of Marseille. The fort forms part of a system with the low outwork you see here and also an older refitted castle, Fort Saint-Jean, on the other side of the harbor.

Photo via Wikimedia Commons.All of this geometry needed to be carefully laid out to ensure that all lines of approach were covered with as much fire as possible and that there were no blindspots along the wall. That in turn meant that the designers of these fortresses needed to be careful with their layout: the spacing, angles and lines all needed to be right, which required quite a lot of math and geometry to manage. Combined with the increasing importance of ballistics for calculating artillery trajectories, this led to an increasing emphasis on mathematics in the “science of warfare”, to the point that some military theorists began to argue (particularly as one pushes into the Enlightenment with its emphasis on the power of reason, logic and empirical investigation to answer all questions) that military affairs could be reduced to pure calculation, a “hard science” as it were, a point which Clausewitz (drink!) goes out of his way to dismiss (as does Ardant du Picq in Battle Studies, but at substantially greater length). But it isn’t hard to see how, in the heady centuries between 1500 and 1800 how the rapid way that science had revolutionized war and reduced activities once governed by tradition and habit to exercises in geometry, one might look forward and assume that trend would continue until the whole affair of war could be reduced to a set of theorems and postulates. It cannot be, of course – the problem is the human element (though the military training of those centuries worked hard to try to turn men into “mechanical soldiers” who could be expected to perform their role with the same neat mathmatical precision of a trace italienne ravelin). Nevertheless this tension – between the science of war and its art – was not new (it dates back at least as far as Hellenistic military manuals) nor is it yet settled.

An aerial view of the Bourtange Fortress in Groningen, Netherlands. Built in 1593, the fort has been restored to its 1750s configuration, seen here.

Photo by Dack9 via Wikimedia Commons.But coming back to our fancy forts, of course such fortresses required larger and larger garrisons to fire all of the muskets and cannon that their firepower oriented defense plans required. Fortunately for the fortress designers, state capacity in Europe was rising rapidly and so larger and larger armies were ready to hand. That causes all sorts of other knock on effects we’re not directly concerned with here (but see the bibliography at the top). For us, the more immediate problem is, well, now we’ve built one of these things … how on earth does one besiege it?

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Fortification, Part IV: French Guns and Italian Lines”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-12-17.

November 28, 2024

QotD: The trace italienne in fortification design

November 22, 2024

QotD: Pre-modern armies on the move

Armies generally had to move over longer distances via roads, for both logistical and pathfinding reasons. For logistics, while unencumbered humans can easily clamber over fences or small ridges or weave through forests, humans carrying heavy loads struggle to do this and pack animals absolutely cannot. Dense forests (especially old growth forests) are formidable obstacles for pack and draft animals, with a real risk of animals injuring themselves with unlucky footfalls. After all the donkey was originally a desert/savannah creature and horses evolved on the Eurasian Steppe; dense forest is a difficult, foreign terrain. But the rural terrain that would dominate most flat, arable land was little better: fields are often split by fences or hedgerows which need to be laboriously cleared (essentially making a path) to allow the work animals through. Adding wagons limits this further; pack mules can make use of narrow paths through forests or hills, but wagons pulled by draft animals require proper roads wide enough to accommodate them, flat enough that the heavy wagon doesn’t slide back and with a surface that will be at least somewhat kind on the wheels. That in turn in many cases restricts armies to significant roadways, ruling out things like farmer’s paths between fields or small informal roads between villages, though smaller screening, scouting or foraging forces could take these side roads.

(As an aside: one my enduring frustrations is the tendency of pre-modern strategy games to represent most flat areas as “plains” of grassland often with a separate “farmland” terrain type used only in areas of very dense settlement. But around most of the Mediterranean, most of the flat, cleared land at lower elevations would have been farmland, with all of the obstructions and complications that implies; rolling grasslands tend to be just that – uplands too hilly for farming.)

The other problem is pathfinding and geolocation. Figuring out where you off-road overland with just a (highly detailed) map and a compass is sufficiently difficult that it is a sport (Orienteering). Prior to 1300, armies in the broader Mediterranean world were likely to lack both; the compass (invented in China) arrives in the Mediterranean in the 1300s and detailed topographical maps of the sort that hikers today might rely on remained rare deep into the modern period, especially maps of large areas. Consequently it could be tricky to determine an army’s exact heading (sun position could give something approximate, of course) or position. Getting lost in unfamiliar territory was thus a very real hazard. Indeed, getting lost in familiar territory was a real hazard: Suetonius records that Julius Caesar, having encamped not far from the Rubicon got lost trying to find it, spent a whole night wandering trying to locate it (his goal being to make the politically decisive crossing with just a few close supporters in secrecy first before his army crossed). In the end he had to find a local guide to work his way back to it in the morning (Suet. Caes. 31.2). So to be clear: famed military genius Julius Caesar got lost trying to find a 50 mile long river only about 150 miles away from Rome when he tried to cut cross-country instead of over the roads.

Instead, armies relied on locals guides (be they friendly, bought or coerced) to help them find their way or figure out where they were on whatever maps they could get together. Locals in turn tend to navigate by landmarks and so are likely to guide the army along the paths and roads they themselves use to travel around the region. Which is all as well because the army needs to use the roads anyway and no one wants to get lost. The road and path network thus becomes a vital navigational aid: roads and paths both lead to settlements full of potential guides (to the next settlement) and because roads tend to connect large settlements and large settlements tend to be the objectives of military campaigns, the road system “points the way”. Consequently, armies rarely strayed off of the road network and were in most cases effectively confined to it. Small parties might be sent out off of the road network from the main body, but the main body was “stuck” on the roads.

That means the general does not have to cope with an infinitely wide range of maneuver possibilities but a spiderweb of possible pathways. Small, “flying columns” without heavy baggage could use minor roads and pathways, but the main body of the army was likely to be confined to well-traveled routes connecting large settlements.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Logistics, How Did They Do It, Part III: On the move”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2022-08-12.

November 16, 2024

QotD: Mao Zedong’s strategy of “protracted war” is a “strategy of the weak”

… the strategy of protracted war [Wiki] has to be adapted for local circumstances and new communications technologies and the ways in which it can be so adapted. But before we talk about how the framework might apply to the current conflict in Ukraine (the one which resulted from Russia’s unprovoked, lawless invasion), I want to summarize the basic features that connect these different kinds of protracted war.

First, the party trying to win a protracted war accepts that they are unable to win a “war of quick decision” – because protracted war tends to be so destructive, if you have a decent shot at winning a war of quick decision, you take it. I do want to stress this – no power resorts to insurgency or protracted war by choice; they do it out of necessity. This is a strategy of the weak. Next, the goal of protracted war is to change the center of gravity of the conflict from a question of industrial and military might to a question of will – to make it about mobilizing people rather than industry or firepower. The longer the war can be protracted, the more opportunities will be provided to degrade enemy will and to reinforce friendly will (through propaganda, recruitment, etc.).

Those concerns produce the “phase” pattern where the war proceeds – ideally – in stages, precisely because the weaker party cannot try for a direct victory at the outset. In the first phase, it is assumes the stronger party will try to use their strength to force that war of quick decision (that they win). In response, the defender has to find ways to avoid the superior firepower of the stronger party, often by trading space for time or by using the supportive population as covering terrain or both. The goal of this phase is not to win but to stall out the attacker’s advance so that the war can be protracted; not losing counts as success early in a protracted war.

That success produces a period of strategic stalemate which enables the weaker party to continue to degrade the will of their enemy, all while building their own strength through recruitment and through equipment supplied by outside powers (which often requires a political effort directed at securing that outside support). Finally, once enemy will is sufficiently degraded and their foreign partners have been made to withdraw (through that same erosion of will), the originally weaker side can shift to conventional “positional” warfare, achieving its aims.

This is the basic pattern that ties together different sorts of protracted war: protraction, the focus on will, the consequent importance of the political effort alongside the military effort, and the succession of phases.

(For those who want more detail on this and also more of a sense of how protracted war, insurgency and terrorism interrelate as strategies of the weak, when I cover this topic in the military history survey, the textbook I use is W. Lee, Waging War: Conflict, Culture and Innovation in World History (2016). Chapter 14 covers these approaches and the responses to them and includes a more expensive bibliography of further reading. Mao’s On Protracted War can be found translated online. Many of Giáp’s writings on military theory are translated and gathered together in R. Stetler (ed.), The Military Art of People’s War: Selected Writings of General Vo Nguyen Giáp (1970).)

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: How the Weak Can Win – A Primer on Protracted War”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2022-03-03.

November 10, 2024

QotD: The low social status of shepherds in the ancient and medieval world

When thinking about the people involved in these activities, at least in most agrarian contexts, it is often important to distinguish between two groups of people: the shepherds themselves who tend the sheep and the often far higher status individuals or organizations which might own the herd or rent out the pasture-land. At the same time there is also often a disconnect between how ancient sources sometimes discuss shepherding and shepherds in general and how ancient societies tended to value actual shepherds in practice.

One the one hand, there is a robust literature, beginning in the Greek and Roman literary corpus, which idealizes rustic life, particularly shepherding. Starting with Theocritus’ short pastoral poems (called eidullion, “little poems” from where we get the word idyll as in calling a scene “idyllic”) and running through Vergil’s Eclogues and Georgics, which present the pure rural simplicity of the countryside and pastoralism as a welcome contrast to the often “sordid” and unhealthy environment of the city (remember the way these “gentlemen farmers” tend to think about merchants and markets in cities, after all). This idolization only becomes more intense in Europe with the advent of Christianity and the grand metaphorical significance that shepherding in particular – as distinct from other rural activities – takes on. It would thus be easy to assume just from reading this sort of high literature that shepherds were well thought of, especially in a Christian social context.

But by and large just as the elite love of the idea of rural simplicity did not generally lead to a love of actual farming peasants, so too their love of the idea of pastoral simplicity did not generally lead to an actually high opinion of the folks who did that work, nor did it lead shepherds to any kind of high social status. While the exact social position of shepherds and their relation to the broader society could vary (as we’ll see), they tended to be relatively low-status and poor individuals. The “shepherds out tending their flocks by night” of Luke 2:8 are not important men. Indeed, the “night crew” of shepherds are some of the lowest status and poorest free individuals who could possibly see that religious sign, a point in the text that is missed by many modern readers.

We see a variety of shepherding strategies which impact what kind of shepherds might be out with flocks. Small peasant households might keep a few sheep (along with say, chickens or pigs) to provide for the household’s wool needs. In some cases, a village might pool those sheep together to make a flock which one person would tend (a job which often seems to have gone to either fairly young individuals or else the elderly – that is, someone who might not be as useful in the hard labor on the farm itself, since shepherding doesn’t necessarily require a lot of strength).

Larger operations by dedicated shepherds often involved wage-laborers or enslaved laborers tending flocks of sheep and pastured owned by other, higher status and wealthier individuals. Thus for instance, Diodorus’s description of the Sicilian slave revolts (in 135 and 104 BC; the original Diodorus, book 36, is lost but two summaries survive, those of Photios and Constantine Porphyrogennetos), we’re told that the the flocks belonging to the large estates of Roman magnates in the lowland down by the coast were tended by enslaved shepherds in significant numbers (and treated very poorly; when a Greek source like Diodorus who is entirely comfortable with slavery is nevertheless noting the poor treatment, it must be poor indeed). Likewise, there is a fair bit of evidence from ancient Mesopotamia indicating that the flocks of sheep themselves were often under state or temple control (e.g. W. Sallaberger, “The Value of Wool in Early Bronze Age Mesopotamia” or S. Zawadzki, “‘If you have sheep, you have all you need’: Sheep Husbandry and Wool in the Economy of the Neo-Babylonian Ebaddar Temple at Sippar” both in Wool Economy in the Ancient Near East and the Aegean eds. C. Breniquet and C. Michel, (2014)) and that it was the temple or the king that might sell or dispose of the wool; the shepherds were only laborers (free or unfree is often unclear).

Full time shepherds could – they didn’t always, but could – come under suspicion as effective outsiders to the fully sedentary rural communities they served as well. Diodorus in the aforementioned example is quick to note that banditry in Sicily was rife because the enslaved shepherds were often armed – armed to protect their flocks because banditry was rife; we are left to conclude that Diodorus at least thinks the banditry in question is being perpetrated by the shepherds, evidently sometimes rustling sheep from other enslaved shepherds. A similar disdain for the semi-nomadic herding culture of peoples like the Amorites is sometimes evident in Mesopotamian texts. And of course that the very nature of transhumance meant that shepherds often spent long periods away from home sleeping with their flocks in temporary shelters and generally “roughing it” exposed to weather.

Consequently, while owning large numbers of sheep and pastures for them could be a contributor to high status (and thus merit elite remark, as with Pliny’s long discussion of sheep in book 8 of his Natural History), actually tending sheep was mostly a low-status job and not generally well remunerated (keeping on poor Pliny here, it is notable that in several long sections on sheep he never once mentions shepherds). Shepherds were thus generally towards the bottom of the social pyramid in most pre-modern societies, below the serf or freeholding farmer who might at least be entitled to the continued use of their land.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Clothing, How Did They Make It? Part I: High Fiber”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-03-05.

November 4, 2024

QotD: Early raids on, and sieges of, fortified cities

We’ve gone over this before, but we should also cover the objectives the attacker generally has in a siege. In practice, we want to think about assaults fitting into two categories: the raid and the siege, with these as distinct kinds of attack with different objectives. The earliest fortifications were likely to have been primarily meant to defend against raids rather than sieges as very early (Mesolithic or Neolithic) warfare seems, in as best we can tell with the very limited evidence, to have been primarily focused on using raids to force enemies to vacate territory (by making it too dangerous for them to inhabit by inflicting losses). Raids are typically all about surprise (in part because the aim of the raid, either to steal goods or inflict casualties, can be done without any intention to stick around), so fortifications designed to resist them do not need to stop the enemy, merely slow them down long enough so that they can be detected and a response made ready. […]

In contrast, the emergence of states focused on territorial control create a different set of strategic objectives which lead towards the siege as the offensive method of choice over the raid. States, with their need to control and administer territory (and the desire to get control of that territory with its farming population intact so that they can be forced to farm that land and then have their agricultural surplus extracted as taxes), aim to gain control of areas of agricultural production, in order to extract resources from them (both to enrich the elite and core of the state, but also to fund further military activity).

Thus, the goal in besieging a fortified settlement (be that, as would be likely in this early period, a fortified town or as later a castle) is generally to get control of the administrative center. Most of the economic activity prior to the industrial revolution is not in the city; rather the city’s value is that it is an economic and administrative hub. Controlling the city allows a state to control and extract from the countryside around the city, which is the real prize. Control here thus means setting up a stable civilian administration within the city which can in turn extract resources from the countryside; this may or may not require a permanent garrison of some sort, but it almost always requires the complete collapse of organized resistance in the city. Needless to say, setting up a stable civilian administration is not something one generally does by surprise, and so the siege has to aim for more durable control over the settlement. It also requires fairly complete control; if you control most of the town but, say, a group of defenders are still holding out in a citadel somewhere, that is going to make it very difficult to set up a stable administration which can extract resources.

Fortunately for potential defenders, a fortification system which can withstand a siege is almost always going to be sufficient to prevent a raid as well (because if you can’t beat it with months of preparatory work, you are certainly unlikely to be able to quickly and silently overcome it in just a few night hours except under extremely favorable conditions), though detection and observation are also very important in sieges. Nevertheless, we will actually see at various points fortification systems emerge from systems designed more to prevent the raid (or similar “surprise” assaults) rather than the siege (which is almost never delivered by surprise), so keeping both potential attacking methods in mind – the pounce-and-flee raid and the assault-and-stay siege – is going to be important.

As we are going to see, even fairly basic fortifications are going to mean that a siege attacker must either bring a large army to the target, or plan to stay at the target for a long time, or both. In a real sense, until very recently, this is what “conventional” agrarian armies were: siege delivery mechanisms. Operations in this context were mostly about resolving the difficult questions of how to get the siege (by which I mean the army that can execute the siege) to the fortified settlement (and administrative center) being targeted. Because siege-capable armies are either big or intend to stick around (or both), surprise is out of the window for these kinds of assaults, which in turn raises the possibility of being forced into a battle, either on the approach to the target or once you have laid siege to it.

It is that fact which then leads to all of the many considerations for how to win a battle, some of which we have discussed elsewhere. I do not want to get drawn off into the question of winning battles, but I do want to note here that the battle is, in this equation, a “second order” concern: merely an event which enables (or prohibits) a siege. As we’ll see, sieges are quite unpleasant things, so if a defender can not have a siege by virtue of a battle, it almost always makes sense to try that (there are some exceptions, but as a rule one does not submit to a siege if there are other choices), but the key thing here is that battles are fundamentally secondary in importance to the siege: the goal of the battle is merely to enable or prevent the siege. The siege, and the capture or non-capture of the town (with its role as an administrative center for the agricultural hinterland around it) is what matters.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Fortification, Part I: The Besieger’s Playbook”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-10-29.

October 29, 2024

QotD: The Roman Republic after the Social War

The Social War coincided with the beginning of Rome’s wars with Mithridates VI of Pontus – the last real competitor Rome had in the Mediterranean world, whose defeat and death in 63 BC marked the end of the last large state resisting Rome and the last real presence of any anti-Roman power on the Mediterranean littoral. Rome was not out of enemies, of course, but Rome’s wars in the decades that followed were either civil wars (the in-fighting between Rome’s aristocrats spiraling into civil war beginning in 87 and ending in 31) or wars of conquest by Rome against substantially weaker powers, like Caesar’s conquests in Gaul.

Mithridates’ effort against the Romans, begun in 89 relied on the assumption that the chaos of the Social War would make it possible for Mithridates to absorb Roman territory (in particular the province of Asia, which corresponds to modern western Turkey) and eventually rival Rome itself (or whatever post-Social War Italic power replaced it). That plan collapsed precisely because Rome moved so quickly to offer citizenship to their disgruntled socii; it is not hard to imagine a more stubborn Rome perhaps still winning the Social War, but at such cost that it would have had few soldiers left to send East. As it was, by 87, Mithridates was effectively doomed, poised to be assailed by one Roman army after another until his kingdom was chipped away and exhausted by Rome’s far greater resources. It was only because of Rome’s continuing domestic political dysfunction (which to be clear had been going on since at least 133 and was not a product of the expansion of citizenship) that Mithridates lasted as long as he did.

More than that, Rome’s success in this period is clearly and directly attributable to the Roman willingness to bring a wildly diverse range of Italic peoples, covering at least three religious systems, five languages and around two dozen different ethnic or tribal identities and forge that into a single cohesive military force and eventually into a single identity and citizen body. Rome’s ability to effectively manage and lead an extremely diverse coalition provided it with the resources that made the Roman Empire possible. And we should be clear here: Rome granted citizenship to the allies first; cultural assimilation only came afterwards.

Rome’s achievement in this regard stands in stark contrast to the failure of Rome’s rivals to effectively do the same. Carthage was quite good at employing large numbers of battle-hardened Iberian and Gallic mercenaries, but the speed with which Carthage’s subject states in North Africa (most notably its client kingdom, Numidia) jumped ship and joined the Romans at the first real opportunity speaks to a failure to achieve the same level of buy-in. Hannibal spent a decade and a half trying to incite a widespread revolt among Rome’s Italian allies and largely failed; the Romans managed a far more consequential revolt in Carthage’s North African territory in a single year.

And yet Carthage did still far better than Rome’s Hellenistic rivals in the East. As Taylor (op. cit.) documents, despite the vast wealth and population of the Ptolemaic and Seleucid states, they were never able to mobilize men on the scale that Rome did and whereas Rome’s allies stuck by them when the going got tough, the non-Macedonian subjects of the Ptolemies and Seleucids always had at least one eye on the door. Still worse were the Antigonids, whose core territory was larger and probably somewhat more populous than the ager Romanus (that is, the territory directly controlled by Rome), but who, despite decades of acting as the hegemon of Greece, were singularly incapable of directing the Greeks or drawing any sort of military resources or investment from them. Lest we attribute this to fractious Greeks, it seems worth noting that the Latin speaking Romans were far better at getting their Greeks (in Southern Italy and Campania) to furnish troops, ships and supplies than the Greek speaking (though ethnically Macedonian) Antigonids ever were.

In short, the Roman Republic, with its integrated communities of socii and relatively welcoming and expansionist citizenship regime (and yes, the word “relatively” there carries a lot of weight) had faced down a collection of imperial powers bent on maintaining the culture and ethnic homogeneity of their ruling class. Far from being a weakness, Rome’s opportunistic embrace of diversity had given it a decisive edge; diversity turned out to be the Romans’ “killer app”. And I should note it was not merely the Roman use of the allies as “warm bodies” or “cannon fodder” – the Romans relied on those allied communities to provide leadership (both junior officers of their own units, but also after citizenship was granted, leadership at Rome too; Gaius Marius, Cicero and Gnaeus Pompey were all from communities of former socii) and technical expertise (the Roman navy, for instance, seems to have relied quite heavily on the experienced mariners of the Greek communities in Southern Italy).

Like the famous Appian Way, Rome’s road to empire had run through not merely Romans, but Latins, Oscan-speaking Campanians, upland Samnites, Messapic-speaking Apulians and coastal Greeks. The Romans had not intended to forge a pan-Italic super-identity or to spread the Latin language or Roman culture to anyone; they had intended to set up systems to get the resources and manpower to win wars. And win wars they did. Diversity had won Rome an empire. And as we’ll see, diversity was how they would keep it.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: The Queen’s Latin or Who Were the Romans, Part II: Citizens and Allies”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-06-25.

October 23, 2024

QotD: Sheep shearing in the ancient and medieval world

Of course you have to get the wool off of the sheep and this is a process that seems to have changed significantly with the dawn of the iron age. The earliest breeds of sheep didn’t grow their coats continuously, but rather stopped growing their fleece in the spring and thus in the late spring the fleece begins to shed and peel away from the body. This seems to be how most sheep “shearing” (I use the term loosely, as no shearing is taking place) was done prior to the iron age. This technique is still used, particularly in the Shetlands, where it is called rooing, but it also occasionally known as “plucking”. It has been surmised that regular knives (typically of bone) or perhaps flint scrapers sometimes found archaeologically might have assisted with this process, but such objects are multi-purpose and difficult to distinguish as being attached to a particular purpose. It has also been suggested that flint scrapers might have been used eventually in the early bronze age shearing of sheep with continuously growing coats, but Breniquet and Michel express doubts (Wool Economy in the Ancient Near East and the Aegean (2014)). Another quirk of this early process and sheep that shed on their own is that unlike with modern sheep shearing, one cannot wash the sheep before removing the wool – since it is already being shed, you would simply wash it away. Plucking or rooing stuck around for certain breeds of sheep in the Roman sphere at least until the first century, but in most places not much further.

The availability of iron for tools represented a fairly major change. Iron, unlike bronze or copper, is springy which makes the standard design of sheep shears (two blades, connected by a u-shaped or w-shaped metal span called a “bow”) and the spring action (the bending and springing back into place of the metal span) possible. The basic design of these blade shears has remained almost entirely unchanged since at least the 8th century BC, with the only major difference I’ve seen being that modern blade shears tend to favor a “w-shape” to the hinge, while ancient shears are made with a simpler u-shape. Ancient iron shears generally varied between 10 to 15cm in length (generally closer to 15 than to 10) and modern shears … generally vary between 10cm and 18.5cm in length; roughly the same size. Sometimes – more often than you might think – the ideal form of an unpowered tool was developed fairly early and then subsequently changed very little.

Modern shearing, either bladed or mechanical, is likely to be done by a specialized sheep shearer, but the overall impression from my reading is that pre-modern sheep shearing was generally done by the shepherds themselves and so was often less of a specialized task with a pastoral community. There are interesting variations in what the evidence implies for the gender of those shearing sheep; shears for sheep are common burial goods in Iron Age Italy, but their gender associations vary by place. In the culturally Gallic regions of North Italy, it seems that shears were assumed to belong to men (based on associated grave goods; that’s a method with some pitfalls, but the consistency of the correlation is still striking), while in Sicily, shears were found in both male and female burials and more often in the latter (but again, based on associated grave goods). Shears also show up in the excavation of settlements in wool-producing regions in Italy.

That said, the process of shearing sheep in the ancient world wasn’t much different from blade shearing still occasionally performed today on modern sheep. Typically before shearing, the sheep are washed to try to get the wool as clean as possible (though further post-shearing cleaning is almost always done); typically this was done using natural bodies of moving water (like a stream or shallow river). The sheep’s legs are then restrained either by hand or being tied and the fleece is cut off; I can find, in looking at depictions of blade shearing in various periods, no consistency in terms of what is sheared first or in what order (save that – as well known to anyone familiar with sheep – that a sheep’s face and rear end are often sheared more often; this is because modern breeds of sheep have been selectively bred to produce so much wool that these areas must be cleared regularly to keep the fleece clean and to keep the sheep from being “wigged” – that is, having its wool block its eyes). Nevertheless, a skilled shearer can shear sheep extremely fast; individuals shearing 100-200 sheep a day is not an uncommon report for modern commercial shearers working with tools that, as noted, are not much different from ancient tools. That speed was important; sheep were generally sheared just once a year and usually in a fairly narrow time window (spring or very early summer; in medieval England this was generally in June and was often accompanied by a rural festival) so getting them all sheared and ready to go before they went up the mountain towards the summer pasture probably did need to be done in fairly short order.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Clothing, How Did They Make It? Part I: High Fiber”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-03-05.

October 17, 2024

QotD: Soldiers and warriors

We want to start with asking what the distinction is between soldiers and warriors. It is a tricky question and even the U.S. Army sometimes gets it badly wrong ([author Steven] Pressfield, I should note, draws a distinction which isn’t entirely wrong but is so wrapped up with his dodgy effort to use discredited psychology that I think it is best to start from scratch). We have a sense that while both of these words mean “combatant”, that they are not quite equivalent.

[…]

But why? The etymologies of the words can actually help push us a bit in the right direction. Warrior has a fairly obvious etymology, being related to war (itself a derivative of French guerre); as guerre becomes war, so Old French guerreieor became Middle English werreior and because that is obnoxious to say, modern English “warrior” (which is why it is warrior and not “warrer” as we might expect if it was regularly constructed). By contrast, soldier comes – it has a tortured journey which I am simplifying – from the sold/sould French root meaning “pay” which in turn comes from Latin solidus, a standard Late Roman coin. So there is clearly something about pay, or the lack of pay involved in this distinction, but clearly it isn’t just pay or the word mercenary would suit just as well.

So here is the difference: a warrior is an individual who wars, because it is their foundational vocation, an irremovable part of their identity and social position, pursued for those private ends (status, wealth, place in society). So the core of what it is to be a warrior is that it is an element of personal identity and also fundamentally individualistic (in motivation, to be clear, not in fighting style – many warriors fought with collective tactics, although I think it fair to say that operation in units is much more central to soldiering than the role of a warrior, who may well fight alone). A warrior remains a warrior when the war ends. A warrior remains a warrior whether fighting alone or for themselves.

By contrast, a soldier is an individual who soldiers (notably a different verb, which includes a sense of drudgery in war-related jobs that aren’t warring per se) as a job which they may one day leave behind, under the authority of and pursued for a larger community which directs their actions, typically through a system of regular discipline. So the core of what it is to be a soldier is that it is a not-necessarily-permanent employment and fundamentally about being both in and in service to a group. A soldier, when the war or their term of service ends, becomes a civilian (something a warrior generally does not do!). A soldier without a community stops being a soldier and starts being a mercenary.

Incidentally, this distinction is not unique to English. Speaking of the two languages I have the most experience in, both Greek and Latin have this distinction. Greek has machetes (μαχητής, lit: “battler”, a mache being a battle) and polemistes (πολεμιστής, lit: “warrior”, a polemos being a war); both are more common in poetry than prose, often used to describe mythical heroes. Interestingly the word for an individual that fights out of battle order (when there is a battle order) is a promachos (πρόμαχος, lit: “fore-fighter”), a frequent word in Homer. But the standard Greek soldier wasn’t generally called any of these things, he was either a hoplite (ὁπλίτης, “full-equipped man”, named after his equipment) or more generally a stratiotes (στρατιώτης, lit: “army-man” but properly “soldier”). That general word, stratiotes is striking, but its root is stratos (στρατός, “army”); a stratiotes, a soldier, for the ancient Greeks was defined by his membership in that larger unit, the army. One could be a machetes or a polemistes alone, but only a stratiotes in an army (stratos), commanded, presumably, by a general (strategos) in service to a community.

Latin has the same division, with similar shades of meaning. Latin has bellator (“warrior”) from bellum (“war”), but Roman soldiers are not generally bellatores (except in a poetic sense and even then only rarely), even when they are actively waging war. Instead, the soldiers of Rome are milites (sing. miles). The word is related to the Latin mille (“thousand”) from the root “mil-” which indicates a collection or combination of things. Milites are thus – like stratiotes, men put together, defined by their collective action for the community (strikingly, groups acting for individual aims in Latin are not milites but latrones, bandits – a word Roman authors also use very freely for enemy irregular fighters, much like the pejorative use of “terrorist” and “insurgent” today) Likewise, the word for groups of armed private citizens unauthorized by the state is not “militia”, but “gang”. The repeated misuse by journalists of “militia” which ought only refer to citizens-in-arms under recognized authority, drives me to madness).

(I actually think these Greek and Latin words are important for understanding the modern use of “warrior” and “soldier” even though they don’t give us either. Post-industrial militaries – of the sort most countries have – are patterned on the modern European military model, which in turn has its foundations in the Early Modern period which in turn (again) was heavily influenced by how thinkers of that period understood Greek and Roman antiquity (which was a core part of their education; this is not to say they were always good at understanding classical antiquity, mind). Consequently, the Greek and Roman understanding of the distinction probably has significant influence on our understanding, though I also suspect that we’d find distinctions in many languages along much the same lines.)

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: The Universal Warrior, Part I: Soldiers, Warriors, and …”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-01-29.

October 11, 2024

QotD: Fascists are inherently bad at war

For this week’s musing, I wanted to take the opportunity to expand a bit on a topic that I raised on Twitter which draw a fair bit of commentary: that fascists and fascist governments, despite their positioning are generally bad at war. And let me note at the outset, I am using fascist fairly narrowly – I generally follow Umberto Eco’s definition (from “Ur Fascism” (1995)). Consequently, not all authoritarian or even right-authoritarian governments are fascist (but many are). Fascist has to mean something more specific than “people I disagree with” to be a useful term (mostly, of course, useful as a warning).

First, I want to explain why I think this is a point worth making. For the most part, when we critique fascism (and other authoritarian ideologies), we focus on the inability of these ideologies to deliver on the things we – the (I hope) non-fascists – value, like liberty, prosperity, stability and peace. The problem is that the folks who might be beguiled by authoritarian ideologies are at risk precisely because they do not value those things – or at least, do not realize how much they value those things and won’t until they are gone. That is, of course, its own moral failing, but society as a whole benefits from having fewer fascists, so the exercise of deflating the appeal of fascism retains value for our sake, rather than for the sake of the would-be fascists (though they benefit as well, as it is, in fact, bad for you to be a fascist).

But war, war is something fascists value intensely because the beating heart of fascist ideology is a desire to prove heroic masculinity in the crucible of violent conflict (arising out of deep insecurity, generally). Or as Eco puts it, “For Ur-Fascism there is no struggle for life, but, rather, life is lived for struggle … life is permanent warfare” and as a result, “everyone is educated to become a hero“. Being good at war is fundamentally central to fascism in nearly all of its forms – indeed, I’d argue nothing is so central. Consequently, there is real value in showing that fascism is, in fact, bad at war, which it is.

Now how do we assess if a state is “good” at war? The great temptation here is to look at inputs: who has the best equipment, the “best” soldiers (good luck assessing that), the most “strategic geniuses” and so on. But war is not a baseball game. No one cares about your RBI or On-Base percentage. If a country’s soldiers fight marvelously in a way that guarantees the destruction of their state and the total annihilation of their people, no one will sing their praises – indeed, no one will be left alive to do so.

Instead, war is an activity judged purely on outcomes, by which we mean strategic outcomes. Being “good at war” means securing desired strategic outcomes or at least avoiding undesirable ones. There is, after all, something to be said for a country which manages to salvage a draw from a disadvantageous war (especially one it did not start) rather than total defeat, just as much as a country that conquers. Meanwhile, failure in wars of choice – that is, wars a state starts which it could have equally chosen not to start – are more damning than failures in wars of necessity. And the most fundamental strategic objective of every state or polity is to survive, so the failure to ensure that basic outcome is a severe failure indeed.

Judged by that metric, fascist governments are terrible at war. There haven’t been all that many fascist governments, historically speaking and a shocking percentage of them started wars of choice which resulted in the absolute destruction of their regime and state, the worst possible strategic outcome. Most long-standing states have been to war many times, winning sometimes and losing sometimes, but generally able to preserve the existence of their state even in defeat. At this basic task, however, fascist states usually fail.

The rejoinder to this is to argue that, “well, yes, but they were outnumbered, they were outproduced, they were ganged up on” – in the most absurd example, folks quite literally argued that the Nazis at least had a positive k:d (kill-to-death ratio) like this was a game of Call of Duty. But war is not a game – no one cares what your KDA is if you lose and your state is extinguished. All that matters is strategic outcomes: war is fought for no other purpose because war is an extension of policy (drink!). Creating situations – and fascist governments regularly created such situations. Starting a war in which you will be outnumbered, ganged up on, outproduced and then smashed flat: that is being bad at war.

Countries, governments and ideologies which are good at war do not voluntarily start unwinnable wars.

So how do fascist governments do at war? Terribly. The two most clear-cut examples of fascist governments, the ones most everyone agrees on, are of course Mussolini’s fascist Italy and Nazi Germany. Fascist Italy started a number of colonial wars, most notably the Second Italo-Ethiopian War, which it won, but at ruinous cost, leading it to fall into a decidedly junior position behind Germany. Mussolini then opted by choice to join WWII, leading to the destruction of his regime, his state, its monarchy and the loss of his life; he managed to destroy Italy in just 22 years. This is, by the standards of regimes, abjectly terrible.

Nazi Germany’s record manages to somehow be worse. Hitler comes to power in 1933, precipitates WWII (in Europe) in 1939 and leads his country to annihilation by 1945, just 12 years. In short, Nazi Germany fought one war, which it lost as thoroughly and completely as it is possible to lose; in a sense the Nazis are necessarily tied for the position of “worst regime at war in history” by virtue of having never won a war, nor survived a war, nor avoided a war. Hitler’s decision, while fighting a great power with nearly as large a resource base as his own (Britain) to voluntarily declare war on not one (USSR) but two (USA) much larger and in the event stronger powers is an act of staggeringly bad strategic mismanagement. The Nazis also mismanaged their war economy, designed finicky, bespoke equipment ill-suited for the war they were waging and ran down their armies so hard that they effectively demodernized them inside of Russia. It is absolutely the case that the liberal democracies were unprepared for 1940, but it is also the case that Hitler inflicted upon his own people – not including his many, horrible domestic crimes – far more damage than he meted out even to conquered France.

Beyond these two, the next most “clearly fascist” government is generally Francisco Franco’s Spain – a clearly right-authoritarian regime, but there is some argument as to if we should understand them as fascist. Francoist Spain may have one of the best war records of any fascist state, on account of generally avoiding foreign wars: the Falangists win the Spanish Civil War, win a military victory in a small war against Morocco in 1957-8 (started by Moroccan insurgents) which nevertheless sees Spanish territory shrink (so a military victory but a strategic defeat), rather than expand, and then steadily relinquish most of their remaining imperial holdings. It turns out that the best “good at war” fascist state is the one that avoids starting wars and so limits the wars it can possibly lose.

Broader definitions of fascism than this will scoop up other right-authoritarian governments (and start no end of arguments) but the candidates for fascist or near-fascist regimes that have been militarily successful are few. Salazar (Portugal) avoided aggressive wars but his government lost its wars to retain a hold on Portugal’s overseas empire. Imperial Japan’s ideology has its own features and so may not be classified as fascist, but hardly helps the war record if included. Perón (Argentina) is sometimes described as near-fascist, but also avoided foreign wars. I’ve seen the Baathist regimes (Assad’s Syria and Hussein’s Iraq) described as effectively fascist with cosmetic socialist trappings and the military record there is awful: Saddam Hussein’s Iraq started a war of choice with Iran where it barely managed to salvage a brutal draw, before getting blown out twice by the United States (the first time as a result of a war of choice, invading Kuwait!), with the second instance causing the end of the regime. Syria, of course, lost a war of choice against Israel in 1967, then was crushed by Israel again in another war of choice in 1973, then found itself unable to control even its own country during the Syrian Civil War (2011-present), with significant parts of Syria still outside of regime control as of early 2024.

And of course there are those who would argue that Putin’s Russia today is effectively fascist (“Rashist”) and one can hardly be impressed by the Russian army managing – barely, at times – to hold its own in another war of choice against a country a fourth its size in population, with a tenth of the economy which was itself not well prepared for a war that Russia had spent a decade rearming and planning for. Russia may yet salvage some sort of ugly draw out of this war – more a result of western, especially American, political dysfunction than Russian military effectiveness – but the original strategic objectives of effectively conquering Ukraine seem profoundly out of reach while the damage to Russia’s military and broader strategic interests is considerable.

I imagine I am missing other near-fascist regimes, but as far as I can tell, the closest a fascist regime gets to being effective at achieving desired strategic outcomes in non-civil wars is the time Italy defeated Ethiopia but at such great cost that in the short-term they could no longer stop Hitler’s Anschluss of Austria and in the long-term effectively became a vassal state of Hitler’s Germany. Instead, the more standard pattern is that fascist or near-fascist regimes regularly start wars of choice which they then lose catastrophically. That is about as bad at war as one can be.

We miss this fact precisely because fascism prioritizes so heavily all of the signifiers of military strength, the pageantry rather than the reality and that pageantry beguiles people. Because being good at war is so central to fascist ideology, fascist governments lie about, set up grand parades of their armies, create propaganda videos about how amazing their armies are. Meanwhile other kinds of governments – liberal democracies, but also traditional monarchies and oligarchies – are often less concerned with the appearance of military strength than the reality of it, and so are more willing to engage in potentially embarrassing self-study and soul-searching. Meanwhile, unencumbered by fascism’s nationalist or racist ideological blinders, they are also often better at making grounded strategic assessments of their power and ability to achieve objectives, while the fascists are so focused on projecting a sense of strength (to make up for their crippling insecurities).

The resulting poor military performance should not be a surprise. Fascist governments, as Eco notes, “are condemned to lose wars because they are constitutionally incapable of objectively evaluating the force of the enemy”. Fascism’s cult of machismo also tends to be a poor fit for modern, industrialized and mechanized war, while fascism’s disdain for the intellectual is a poor fit for sound strategic thinking. Put bluntly, fascism is a loser’s ideology, a smothering emotional safety blanket for deeply insecure and broken people (mostly men), which only makes their problems worse until it destroys them and everyone around them.

This is, however, not an invitation to complacency for liberal democracies which – contrary to fascism – have tended to be quite good at war (though that hardly means they always win). One thing the Second World War clearly demonstrated was that as militarily incompetent as they tend to be, fascist governments can defeat liberal democracies if the liberal democracies are unprepared and politically divided. The War in Ukraine may yet demonstrate the same thing, for Ukraine was unprepared in 2022 and Ukraine’s friends are sadly politically divided now. Instead, it should be a reminder that fascist and near-fascist regimes have a habit of launching stupid wars and so any free country with such a neighbor must be on doubly on guard.

But it should also be a reminder that, although fascists and near-fascists promise to restore manly, masculine military might, they have never, ever actually succeeded in doing that, instead racking up an embarrassing record of military disappointments (and terrible, horrible crimes, lest we forget). Fascism – and indeed, authoritarianisms of all kinds – are ideologies which fail to deliver the things a wise, sane people love – liberty, prosperity, stability and peace – but they also fail to deliver the things they promise.

These are loser ideologies. For losers. Like a drunk fumbling with a loaded pistol, they would be humiliatingly comical if they weren’t also dangerous. And they’re bad at war.

Bret Devereaux, “Fireside Friday, February 23, 2024 (On the Military Failures of Fascism)”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2024-02-23.

October 5, 2024

QotD: The polis as a physical place

A polis is also a place made up of physical spaces. Physically, the Greeks understood a polis to be made up of city itself, which might just be called the polis but also the astu (ἄστυ, “town”), and the hinterland or countryside, generally called the chora (χώρα). The fact that the word polis can mean both the city and the (city+chora=state) should already tell you something about the hierarchy envisaged here: the city is the lord of the chora. Now in the smallest of poleis that might make a lot of sense because nearly everyone would live in the town anyway: in a polis of, say, 150km2, no point might be more than 8 or 9 kilometers from the city center even if it is somewhat irregularly shaped. A farmer could thus live in the city and walk out – about an hour or two, a human can walk 6-7km per hour – each morning.

But in a larger polis – and remember, a lot of Greeks lived in larger poleis even though they were few, because they were large – the chora was going to be large enough to have nucleated settlements like villages in it; for very large poleis it might have whole small towns (like Eleusis or Thoricus/Laurion in Attica, the territory of Athens) as part of the chora. But we usually do not see a sort of nested heirarchy of sites in larger poleis; instead there is the astu and then the chora, the latter absorbing into its meaning any small towns, villages (the term here is usually kome), isolated homesteads or other settlements. The polis in the sense of the core city at the center of the community was not a settlement first-among-equals but qualitatively different from every other settlement in the polis – an ideal neatly expressed in that the name of the city served as synecdoche for the entire community (imagine if it was normal to refer to all Canadians as “Ottawans” regardless of if they lived in Ottawa and indeed to usually do so and to only say “Canada” when it was very clear you meant the full extent of its land area).

That is not to say that the astu and chora were undivided. Many poleis broke up their territory into neighborhood units, called demes (δημοι) or komai (κῶμαι, the plural of kome used already) for voting or organizational purposes and we know in Athens at least these demes had some local governing functions, organizing local festivals and sometimes even local legal functions, but never its own council or council hall (that is, no boule or bouleuterion; we’ll get to these next time), nor its own mint, nor the ability to make or unmake citizen status.

There are also some physical places in the town center itself we should talk about. Most poleis were walled (Sparta was unusual in this respect not being so), with the city core enclosed in a defensive circuit that clearly delineated the difference between the astu and the chora; smaller settlements on the chora were almost never walled. But then most poleis has a second fortified zone in the city, an acropolis (ἀκρόπολις, literally “high city”), an elevated citadel within the city. The acropolis often had its own walls, or (as implied by the name) was on some forbidding height within the city or frequently both. This developed in one of two ways: in many cases settlement began on some defensible hill and then as the city grew it spilled out into the lowlands around it; in other cases villages coalesced together and these poleis might not have an acropolis, but they often did anyway. The acropolis of a polis generally wasn’t further built on, but rather its space was reserved for temples and sometimes other public buildings (though “oops [almost] all temples” acropoleis aren’t rare; temples were the most important buildings to protect so they go in the most protected place!).

While the street structure of poleis was generally organic (and thus disorganized), almost every polis also had an agora (ἀγορά), a open central square which seems to have served first as a meeting or assembly place, but also quickly became a central market. In most poleis, the agora would remain the site for the assembly (ekklesia, ἐκκλησία, literally “meeting” or “assembly”), a gathering-and-voting-body of all citizens (of a certain status in some systems); in very large poleis (especially democratic ones) a special place for the assembly might exist outside the agora to allow enough space. In Athens this was the Pnyx but in other large poleis it might be called a ekklesiasterion. The agora would almost always have a council house called a bouleuterion where a select council, the boule (βουλή) would meet; we’ll talk about these next time but it is worth noting that in most poleis it was the boule, not the ekklesia that was the core institution that defined polis government. In addition the agora would also house in every polis a prytaneion, a building for the leading magistrates which always had a dining room where important guests and citizens (most notably citizens who were Olympic victors) could be dined at state expense. Dedicated court buildings might also be on the agora, but these are rarer; in smaller poleis often other state buildings were used to house court proceedings. Also, there are almost always temples in the agora as well; please note the agora is never on the acropolis, but almost always located at the foot of the hill on which the acropolis sits, as in Athens.

And this is a good point to reiterate how these are general rules, especially in terms of names. Every polis is a little different, but only a little. So the Athenian ekklesiaterion was normally on the Pnyx (and sometimes in the Theater of Dionysus, an expedient used in other poleis too since theaters made good assembly halls), the Spartan boule is the gerousia, the acropolis of Thebes was the Cadmeia and so on. Every polis is a little different, but the basic forms are recognizable in each, even in relatively strange poleis like Sparta or Athens. But it really is striking that self-governing Greek settlements from Emporiae (Today, Empúries, Spain) to Massalia (Marseille, France) to Cyrene (in modern Libya) to Panticapaeum (in Crimea, which is part of Ukraine) tend to feature identifiably similar public buildings mirroring their generally similar governing forms.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: How to Polis, 101: Component Parts”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2023-03-10.

September 29, 2024

QotD: Pyrrhus, King of Epirus

Last time, we sought to assess some of the assumed weaknesses of the Hellenistic phalanx in facing rough terrain and horse archer-centered armies and concluded, fundamentally, that the Hellenistic military system was one that fundamentally worked in a wide variety of environments and against a wide range of opponents.

This week, we’re going to look at Rome’s first experience of that military system, delivered at the hands of Pyrrhus, King of Epirus (r. 297-272). The Pyrrhic Wars (280-275) are always a sticking point in these discussions, because they fit so incongruously with the rest. From 214 to 148, Rome will fight four “Macedonian Wars” and one “Syrian War” and utterly demolish every major Hellenistic army it encounters, winning every single major pitched battle and most of them profoundly lopsidedly. Yet Pyrrhus, fighting the Romans some 65 years earlier manages to defeat Roman armies twice and fight a third to a messy draw, a remarkably better battle record than any other Hellenistic monarch will come anywhere close to achieving. At the same time, Pyrrhus, quite famously, fails to get anywhere with his victories, taking losses he can ill-afford each time (thus the notion of a “Pyrrhic victory”), while the Roman armies he fights are never entirely destroyed either.

So we’re going to take a more in-depth look at the Pyrrhic Wars, going year-by-year through the campaigns and the three major battles at Heraclea (280), Ausculum (279) and Beneventum (275) and try to see both how Pyrrhus gets a much better result than effectively everyone else with a Hellenistic army and also why it isn’t enough to actually defeat the Romans (or the Carthaginians, who he also fights). As I noted last time, I am going to lean a bit in this reconstruction on P.A. Kent, A History of the Pyrrhic War (2020), which does an admirable job of untangling our deeply tangled and honestly quite rubbish sources for this important conflict.

Believe it or not, we are actually going to believe Plutarch in a fair bit of this. So, you know, brace yourself for that.

Now, Pyrrhus’ campaigns wouldn’t have been possible, as we’ll note, without financial support from Ptolemy II Philadelphus, Antigonus II Gonatus and Ptolemy Keraunos. So, as always, if you want to help me raise an Epirote army to invade Italy (NATO really complicates this plan, as compared to the third century, I’ll admit), you can support this project on Patreon.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Phalanx’s Twilight, Legion’s Triumph, Part IIIb: Pyrrhus”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2024-03-08.

September 23, 2024

QotD: On Roman Values

I wanted to use this week’s fireside to muse a bit on a topic I think I may give a fuller treatment to later this year, which is the disconnect between what it seems many “radical traditionalists” imagine traditional Roman values to be and actual Roman cultural values.

Now, of course it isn’t surprising to see Roman exemplars mobilized in support of this or that value system, as people have been doing that since the Romans. But I think the disconnect between how the Romans actually thought and the way they are imagined to have thought by some of their boosters is revealing, both of the roman worldview and often the intellectual and moral poverty of their would-be-imitators.

In particular, the Romans are sometimes adduced by the “RETVRN” traditionalist crowd as fundamentally masculine, “manly men” – “high testosterone” fellows for whom “manliness” was the chief virtue. Romans (and Greeks) are supposed to be super-buff, great big fellows who most of all value strength. One fellow on Twitter even insisted that the chief Roman value was VIRILITAS, which was quite funny, because virilitas (“manhood, manliness”) is an uncommon word in Latin, but when it appears it is mostly as a polite euphemism for “penis”. Simply put, this vision bears little relation to actual Roman values. Roman encomia or laudationes (speeches in praise of something or someone) don’t usually highlight physical strength, “high testosterone” (a concept the Romans, of course, did not have) or even general “manliness”. Roman statues of emperors and politicians may show them as reasonably fit, but they are not ultra-ripped body-builders or Hollywood heart-throbs.

Bret Devereaux, “Fireside Friday, March 29, 2024 (On Roman Values)”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2024-03-29.

September 17, 2024

QotD: “Megacorporations” in history and fiction

I think it is worth stressing here, even in our age of massive mergers and (at least, before the pandemic) huge corporate profits, just how vast the gap in resources is between large states and the largest companies. The largest company by raw revenue in the world is Walmart; its gross revenue (before expenses) is around $525bn. Which sounds like a lot! Except that the tax revenue of its parent country, the United States, was $3.46 trillion (in 2019). Moreover, companies have to go through all sorts of expenses to generate that revenue (states, of course, have to go about collecting taxes, but that’s far cheaper; the IRS’s operating budget is $11.3bn, generating a staggering 300-fold return on investment); Walmart’s net income after the expenses of making that money is “only” $14.88bn. If Walmart focused every last penny of those returns into building a private army then after a few years of build-up, it might be able to retain a military force roughly on par with … the Netherlands ($12.1bn); the military behemoth that is Canada ($22.2bn US) would still be solidly out of reach. And that’s the largest company in the world!

And that data point brings us to our last point – and the one I think is most relevantly applicable for speculative fiction megacorporations – historical megacorporations (by which I mean “true” megacorps that took on major state functions over considerable territory, which is almost always what is meant in speculative fiction) are products of imperialism, produced by imperial states with limited state capacity “outsourcing” key functions of imperial rule to private entities. And that explains why it seems that, historically, megacorporations don’t dominate the states that spawn them: they are almost always products and administrative arms of those states and thus still strongly subordinate to them.

I think that incorporating that historical reality might actually create storytelling opportunities if authors are willing to break out of the (I think quite less plausible) paradigm of megacorporations dominating the largest and most powerful communities that appear so often in science fiction. What if, instead of a corporate-dominated Earth (or even a corp-dominated Near-Future USA), you set a story in a near-future developing country which finds itself under the heel of a megacorporation that is essentially an arm of a foreign government, much like the EIC and VOC? Of course that would mean leavening the anti-capitalist message implicit in the dystopian megacorporation with an equally skeptical take about the utility of state power (it has always struck me that while speculative fiction has spent decades warning about the dangers of capitalist-corporate-power, the destructive potential of state power continues to utterly dwarf the damage companies do. Which is not to say that corporations do no damage of course, only that they have orders of magnitude less capability – and proven track record – to do damage compared to strong states).

(And as an aside, I know you can make an argument that Cyberpunk 2077 does actually adopt this megacorporation-as-colonialism framing, but that’s simply not how the characters in the game world think about or describe Arasoka – the biggest megacorp – which, in any event, appears to have effectively absorbed its home-state anyway. Arasoka isn’t an agent of the Japanese government, it is rather a global state in its own right and according to the lore has effectively controlled its home government for almost a century by the time of the game.)

In any event, it seems worth noting that the megacorporation is not some strange entity that might emerge in the far future with some sort of odd and unpredictable structure, but instead is a historical model of imperial governance that has existed in the past and (one may quibble here with definitions) continues to exist in the present. And, frankly, the historical version of this unusual institution is both quite different from the dystopian warnings of speculative fiction, but also – I think – rather more interesting.

Bret Devereaux, “Fireside Friday: January 1, 2021”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-01-01.

September 11, 2024