The Great War

Published on 12 Jul 2018The Macedonian Front has been quite since the recapture of Monastir except for some minor battles like at Skra. But the five nation Army of the Orient wants to change that and is readying a new offensive.

July 13, 2018

The Gardeners Of Salonica Prepare A New Offensive I THE GREAT WAR Week 207

May 1, 2018

Sikh separatists (and even terrorists) are being protected by the federal government

There’s no reason that Canadian Sikhs can’t agitate for their fellow Sikhs in India to create a separate country in the Punjab, but that freedom must not include active support for terrorists. The Canadian government is looking particularly bad on this front, and it isn’t just because of Justin Trudeau’s farcical adventures on his recent trip to India. None of the major federal parties want to appear to be anti-Sikh, as Sikh voters cluster in several key swing ridings around the country, and any criticism of the terrorists is spun as an attack on all Sikhs. At Quillette Terry Milewski details the government’s unwillingness to deal with the problem:

The Sikh faith, created in what is now northern India by the 15th-century Guru Nanak, remains obscure to many in the West. Turbaned Sikh men are sometimes confused with Muslims, and some have been assaulted by confused thugs following Islamist terrorist attacks. Like the United States, Britain and other Western countries, Canada has been home to emigrant Sikhs for generations—the vast majority of them living peaceably in their adopted homeland.

In the 1980s, however, a powerful spasm of separatist militancy shook India and spread to the Sikh diaspora. In June, 1984, two months before the Madison Square Garden convention, Prime Minister Gandhi and her government set out to end a killing spree by Sikh militants who had turned the Sikhs’ holiest site — the Golden Temple at Amritsar — into an armed camp. The Indian army wrecked the temple complex and took many lives. Revenge came on October 31, 1984, when Gandhi was gunned down in her garden by two of her Sikh bodyguards. Hindu mobs immediately took revenge for the revenge, slaughtering thousands of Sikhs in hellish reprisals that were aggravated by official complicity. The police looked the other way. The horrors of 1984 won’t be forgotten by either side.

Soon, Canada and its Sikh community were dragged into the thick of the struggle. In June of 1985, Parmar’s Babbar Khalsa placed suitcase bombs on two planes leaving Vancouver. One brought down Flight 182, a massacre that remained, until 9/11, the deadliest terrorist attack in the history of aviation. The second bomb, intended to destroy another Air India plane simultaneously, exploded on the ground at Narita Airport in Japan, killing two baggage handlers. The reverberations from the attack were so profound in Canada that even today, 33 years later, a striking emblem of the Khalistani dream survives: a large “martyr” poster honouring Talwinder Parmar, sword in hand, permanently fixed to the exterior of an important Sikh gurdwara in Surrey, British Columbia. Tens of thousands gather beneath it each spring for an annual Sikh parade. In American terms, the poster is equivalent to a public veneration of Osama Bin Laden.

[…]

Today, the parents who lost their children [on Air India Flight 182] are old, the orphaned children have their own children and the Sikh struggle for independence is moribund in India. Last year, in fact, Sikh voters overwhelmingly supported a united India and were key to the election of the Congress Party — the party of Indira Gandhi — to govern the Sikh homeland of Punjab. Support for Congress was especially strong in majority-Sikh districts. And Punjab’s Chief Minister is a strongly pro-unity Sikh, Amarinder Singh, who has alleged separatist influence in the Canadian government.

Harjit Sajjan, a Sikh who is Canada’s Minister of National Defence, firmly denied the claim. And on Justin Trudeau’s visit to India this year, Singh agreed to a photo-op including Sajjan. But the Chief Minister let it be known that he’d handed over a list of Canadians he suspects of fundraising for Punjab’s few remaining separatist Sikh militants.

The listed suspects amount to a tiny subculture among Canada’s 450,000 Sikhs, the vast bulk of whom seek no return to the bloody 1980s and 1990s, when the battle for Khalistan took some 20,000 lives in India, most of them Sikh. But the hardliners are a well-organized political force, still raising the cry of “Khalistan Zindabad!” — long live Khalistan — in some Canadian gurdwaras where “martyred” Sikh assassins are memorialized as models for the young. These include the two bodyguards who machine-gunned Indira Gandhi. Khalistani fervour is alive on social media and a 2018 tweet from “George” (@PCPO_Brampton) declared: “Indira’s assassins are HEROES. Sikhs should glorify them.”

The endurance of such attitudes in Canada reflects the weak record of its justice system in deterring violence. For years, it seemed, Canadian courts were where terrorism cases went to die.

January 19, 2018

Assassination Attempt on Lenin – Chaos in Romania I THE GREAT WAR Week 182

The Great War

Published on 18 Jan 2018This week in Russia, Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin was almost killed by sharpshooters in Petrograd and the Constituent Assembly meets. Tensions rise as Russia issues an ultimatum to Romania, with an order for their King’s arrest. There are also machinations in Finland and some action on the Western Front.

December 30, 2016

Turmoil in Russia – The Assassination of Rasputin I THE GREAT WAR Week 127

Published on 29 Dec 2016

The chaos within Russia, especially Petrograd, is getting more and more severe. In the centre of much controversy is the Tsarina herself and her trusted mystic and healer Grigori Rasputin. His influence over the Tsar and his wife are actively frowned upon and this week 100 yeas ago he is assassinated. At the same the Russians are facing the German Army on the Romanian Front.

December 27, 2016

Rasputin – The Man Behind The Tsarina I WHO DID WHAT IN WW1?

Published on 26 Dec 2016

Grigori Rasputin is as much a man as he is a legend. The mystic behind the Tsar and the Tsarina who apparently made no decision without consulting him. The healer that could perform miracles. The man who was killed for his influence in a time ripe for revolution.

December 21, 2016

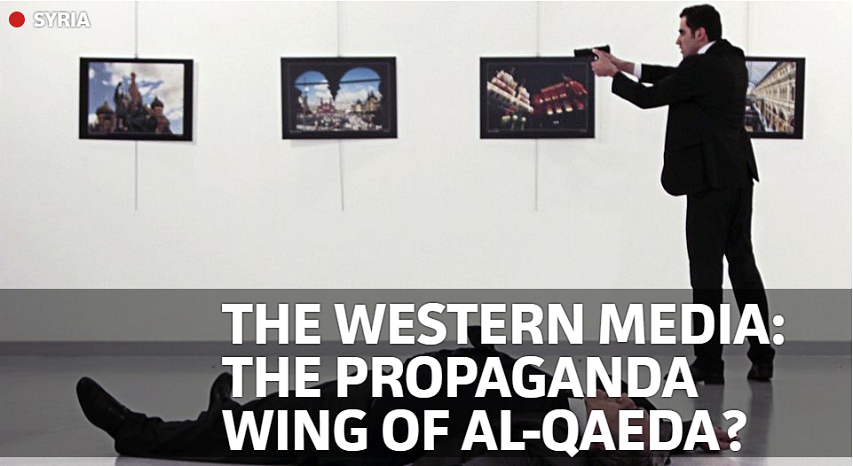

The western press has been colonized by ISIS/al Qaeda

Brendan O’Neill on the way western media have been trained to report certain events to benefit terrorist organizations:

The British press is morphing into a mouthpiece for al-Qaeda. Consider its coverage of yesterday’s assassination of Andrei Karlov, the Russian ambassador to Turkey. It is borderline sympathetic. The killer’s words — or rather, certain of the killer’s words — have been turned into emotional headlines, into condemnations of Russia’s actions in Syria. That the killer’s first and loudest cry was ‘Allahu Akbar’ — the holler of the modern terrorist — has been downplayed, and in the case of at least one newspaper, the Express, completely ignored. Instead the papers upfront the killer’s other cries, about Aleppo. ‘This is for Aleppo’, says The Times. ‘Remember Aleppo’, says the Mirror’s headline, but with no quote marks, because these were not the exact words spoken by the gunman — they’re more like the Mirror’s own sympathetic echo of the killer’s sentiment.

To get a sense of how disturbing, or at least unusual, this coverage is, imagine if the 2013 murder of British soldier Lee Rigby by two Islamists had led to headlines like ‘This is for Afghanistan’ or ‘Remember Basra’ (those two knifemen, like Karlov’s killer, justified their action as a response to militarism overseas). Or if the 7/7 bombings had not given rise to front pages saying ‘Terror bombs explode across London’ or ‘BASTARDS’ but rather ‘While you kill us in Iraq, we will kill you here’. Reading the early coverage of Karlov’s killing, and noting how different it is to British press coverage of other acts of Islamist terror, one gets the impression that the media think this killing is justified, or at least understandable. ‘Remember Aleppo’: they’re saying this as much as the killer is — a perverse union of terrorist and editorial intent.

But the killer said, first, ‘Allahu Akbar’. Which perhaps suggests that his sympathy was not with Syria as such but with certain forces in Syria. Forces likely to shout ‘Allahu Akbar’ as they kill people. Islamist forces. Something peculiar has happened in British media and political circles in recent weeks. Having spent years telling us al-Qaeda-style groups are the greatest threat to our way of life, these people have lately become spectacularly uncritical about, and even weirdly supportive of, the existence and influence of al-Qaeda-style groups in Syria. The press coverage of Karlov’s killing is in keeping with the superbly reductive, highly moralised media coverage of events in Aleppo over the past fortnight, in which there are apparently only two sides: defenceless civilians and evil Russia and Assad. The militants in Aleppo, which include some grotesquely illiberal and misanthropic groups, have been airbrushed out of the coverage as surely as some reporters airbrushed away, or at least demoted to paragraph six, the Turkish assassin’s cry of ‘Allahu Akbar’.

December 16, 2016

ESR on the “Trump is Hitler!” meme

He posted this the other day on Google+:

Reading this [link] put me in mind of a slightly different scenario. So I’m throwing this gauntlet down to anyone who has ever said the “Trump is Hitler” thing.

There are only two possibilities.

One is that you believe what you’re saying. in which case you have a moral duty to find Trump and kill him. With a scoped rifle. With a suicide vest. With hands and teeth. With anything.

The other is that you don’t actually believe Trump is Hitler, but find it advantageous to say so, posturing for demagogic political gain.

If you’re not a liar and a demagogue, why are you not strapping on weapons right now? Put the fuck up or shut the fuck up

May 29, 2016

Dazzle Camouflage – Sabotage Operations I OUT OF THE TRENCHES

Published on 28 May 2016

Chair of Wisdom Time! This week we talk about Dazzle Camouflage and Sabotage Operations.

September 12, 2015

Nash The Slash – Psychotic Reaction

Published on 20 Jun 2013

From His 1984 LP American Bandages

April 15, 2015

Samizdata on the causes of World War 1

Actually, the title is somewhat misleading, as part 1 of Patrick Crozier’s article concentrates on the (rather Anglo-centric) events of 1915:

But at the time, the British in particular, were short of everything. This would come to a head soon afterwards when Repington, again, claimed that the Battle of Neuve Chapelle could have gone much better had the British had enough shells. This would lead almost immediately to the creation of the Ministry of Munitions under Lloyd George.

By this time food prices were beginning to rise. Some foods were already up by 50%. Given that a large proportion of the average person’s income went on food this was inevitably causing hardship. Worse still, this rise took place before the Germans declared the waters around the UK a warzone. I must confess I don’t entirely understand the ins and outs of this but essentially this means that submarines could sink shipping without warning. The upshot was that rationing would be introduced later in the war.

Government control also came to pubs with restricted opening hours. It would even become illegal to buy a round.

So far the Royal Navy had not had a good war. It had let the German battle cruiser Goeben slip through its fingers in the Mediterranean and into Constantinople where it became part of the Ottoman navy which attacked Russia. An entire squadron was destroyed off the coast of Chile and even the victories were hollow. At the Battle of Dogger Bank the chance to destroy a squadron of German battle cruisers was lost due to a signalling error.

[…]

In Britain we tend to think of the First World War as being worse than the Second. This is because, almost uniquely amongst the participants, British losses in the First World War were worse. It is also worth bearing in mind that Britain’s losses in the First World War were much lower than everyone else’s. France lost a million and a half, Germany 2 million. Russia’s losses are anyone’s guess. For all the talk of tragedy and futility, the truth is that Britain got off lightly.

For many libertarians the First World War is particularly tragic. They tend to think (not entirely correctly) of the period before it as a libertarian golden age. While there was plenty of state violence to go around, there were much lower taxes, far fewer planning regulations, few nationalised industries, truly private railways and individuals were allowed to own firearms. If you were in the mood for smoking some opium you needed only to wander down to the nearest chemist.

In part 2, we actually get to some of the proximate causes that triggered the fighting:

So, what caused this catastrophe? If any of you are unfamiliar with the story it might be an idea to get out your smart phones out and pull up a map of Europe in 1914. When you do so you will notice that although western Europe is much the same as it is today, central Europe is completely different. There are far fewer borders and a country called Austria-Hungary occupies a large part of it.

As most of you will know on 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir presumptive to the Austrian throne was assassinated in Sarajevo the capital of Bosnia which he was visiting while inspecting army manoeuvres. Bosnia at the time was a recently-acquired part of the Austrian Empire having been formally incorporated in 1908. Although the Austrians didn’t know this at the time – though they certainly suspected it – Gavrilo Princip, the assassin, and his accomplices had been armed and trained by Serbia’s rogue intelligence service. I say “rogue” because the official Serbian government seems to have had little control over the service run by one Colonel Apis. Apis, as it happens, was executed by the Serbian government in exile in Greece in 1917 and there’s a definite suspicion that old scores were being settled.

Oddly enough, the Austrians weren’t that bothered by the assassination of Franz Ferdinand the man. Apart from his family no one seems to have liked him much. His funeral was distinctly low key although there was a rather touching display by about a 100 nobles who broke ranks to follow the coffin on its way to the station. More importantly, Franz Ferdinand was one of the few doves in a sea of hawks. Most of the Austrian hierarchy wanted war with Serbia. Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf, the Chief of Staff had advocated war with Serbia over 20 times. Franz Ferdinand did not want war with Serbia. He felt that Slav nationalism was something that had to be accepted and the only way of doing this was to give Slavs a similar status to that Hungary had obtained in 1867. So his death changed the balance of power in Vienna. Much as the hierarchy were not bothered by the assassination of Franz Ferdinand the man, they were bothered by the assassination of Franz Ferdinand the symbol – the symbol of Austria’s monarchy and Empire, that is. The Serbs wanted to unite all the South Slavs: that is Slovenes, Croatians, Bosnians, Montenegrins and Macedonians in one state. However, most of these peoples lived in Austria. Now, if the South Slavs left there was no reason to think that the Czechs, Poles, Ruthenes or Romanians who were also part of the Austrian Empire would want to stay. Therefore, it was clear that Serbia’s ambitions posed an existential threat to Austria (correctly as it turned out). The solution? crush Serbia. And now the Austrians had a pretext.

For a longer look at the causes of WW1, I modestly point you to my (long) series of posts from last year on the subject.

Update: About an hour after this post went up, Patrick posted the third part of his series at Samizdata.

December 9, 2014

Colby Cosh on the recent “unprecedented” terror attacks

In his latest Maclean’s article, Colby Cosh talks about the recent “freelance” terror attacks on Canadian soil and points out that no matter what the reporters say, they’re hardly “unprecedented”:

There has been much discussion about how to think of the type of freelance Islamist terrorist that has recently begun to belabour Canada. What labels and metaphors are appropriate for such an unprecedented phenomenon? I possess the secret: It is not unprecedented. This has been kept a secret only through some odd mischance, some failure of attention that is hard to explain.

I discovered the secret through reading about 19th-century history, particularly the years from the 1848 revolutions to the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. The key was Bismarck, the Prussian minister-president who unified Germany. If you want to learn about Bismarck, you will probably pick up a book by some historian of international relations, such as A.J.P. Taylor. That’s the right place to start. But it means you can read a lot about Bismarck before finding out about the time in May 1866 when a guy shot him.

Ferdinand Cohen-Blind, a Badenese student of pan-German sentiments, waylaid Bismarck with a pistol on the Unter den Linden. He fired five rounds. None missed. Three merely grazed his midsection, and two ricocheted off his ribs. He went home and ate a big lunch before letting himself be examined by a doctor.

[…]

The point is not that Bismarck was particularly hated, although he was. The point is that this period of European (and American) history was crawling with young, often solitary male terrorists, most of whom showed signs of mental disorder when caught and tried, and most of whom were attached to some prevailing utopian cause. They tended to be anarchists, nationalists or socialists, but the distinctions are not always clear, and were not thought particularly important. The 19th-century mind identified these young men as congenital conspirators. It emphasized what they had in common: social maladjustment, mania, an overwhelming sense of mission and, usually, a prior record of minor crimes.

In my Origins of WW1 series, I quoted from The War That Ended Peace (which I still heartily recommend):

Margaret MacMillan describes the typical members of the Young Bosnians, who were of a type that we probably recognize more readily now than at any time since 1914:

[They] were mostly young Serb and Croat peasant boys who had left the countryside to study and work in the towns and cities of the Dual Monarchy and Serbia. While they had put on suits in place of their traditional dress and condemned the conservatism of their elders, they nevertheless found much in the modern world bewildering and disturbing. It is hard not to compare them to the extreme groups among Islamic fundamentalists such as Al Qaeda a century later. Like those later fanatics, the Young Bosnians were usually fiercely puritanical, despising such things as alcohol and sexual intercourse. They hated Austria-Hungary in part because they blamed it for corrupting its South Slav subjects. Few of the Young Bosnians had regular jobs. Rather they depended on handouts from their families, with whom they had usually quarreled. They shared their few possessions, slept on each other’s floors, and spent hours over a single cup of coffee in cheap cafés arguing about life and politics. They were idealistic, and passionately committed to liberating Bosnia from foreign rule and to building a new and fairer world. Strongly influenced by the great Russian revolutionaries and anarchists, the Young Bosnians believed that they could only achieve their goals through violence and, if necessary, the sacrifice of their own lives.

The “peaceful century” from the defeat of Napoleon to the outbreak of the First World War was far from peaceful — we only see it as such in contrast to the bloodbath of 1914-1918. And terrorists of a type we readily recognize from the front pages of the newspapers today were prefigured exactly by the anarchist revolutionaries of a century ago.

August 24, 2014

Who is to blame for the outbreak of World War One? (Part twelve of a series)

You can catch up on the earlier posts in this series here (now with hopefully helpful descriptions):

- Why it’s so difficult to answer the question “Who is to blame?”

- Looking back to 1814

- Bismarck, his life and works

- France isolated, Britain’s global responsibilities

- Austria, Austria-Hungary, and the Balkan quagmire

- The Anglo-German naval race, Jackie Fisher, and HMS Dreadnought

- War with Japan, revolution at home: Russia’s self-inflicted miseries

- The First Balkan War

- The Second Balkan War

- The Entente Cordiale, Moroccan crises, and the influence of public opinion

- The Bosnian crisis of 1908

Who’s at the wheel? The less-than-transparent-or-unified governments of 1914

A common reaction (among both modern historians and lay readers) to the apparent incoherence of the decision-making process in the various great powers’ capitals is to ask just who exactly was in command when such-and-such a decision was taken. This reflects on our modern day belief that power has an identifiable source, and that actors had clear direction from a central authority. As Christopher Clark takes pains to outline in The Sleepwalkers this was not true even of the more centralized great powers:

… even a very cursory look at the governments of early twentieth-century Europe reveals that the executive structures from which policies emerged were far from unified. Policy-making was not the prerogative of single sovereign individuals. Initiatives with a bearing on the course of a country’s policy could and did emanate from quite peripheral locations in the political structure. Factional alignments, functional frictions within government, economic or financial constraints and the volatile chemistry of public opinion all exerted a constantly varying pressure on decision-making processes. As the power to shape decisions shifted from one node in the executive structure to another, there were corresponding oscillations in the tone and orientation of policy. This chaos of competing voices is crucial to understanding the periodic agitation of the European system during the last pre-war years. It also helps to explain why the July Crisis of 1914 became the most complex and opaque political crisis of modern times.

In The War That Ended Peace, Margaret MacMillan writes:

Old institutions and values were under attack and new ways and new attitudes were emerging. Their world was changing, perhaps too fast, and they had to attempt to make sense of it. “What were they thinking?” is a question often asked about the Europeans who went to war in 1914. The ideas that influenced their view of the world, what they took for granted without discussion (what the historian James Joll called “unspoken assumptions”), what was changing and what was not, all are important parts of the context within which war, even a general European war, became a possible option in 1914.

The uneasy state of the Serbian state

Serbia had been practically an independent state since shrugging off the last Ottoman military occupation in 1867 and that independence was formally recognized by the great powers in 1878 at the Congress of Berlin which was the peace conference called to end the Russo-Turkish War (which we briefly looked at in part two). One of the provisions of the treaty that strongly displeased the Serbs was that they were forbidden to take over Bosnia, which instead was placed in the care of the Austro-Hungarian empire: the Serbs had gone to war with the Ottomans in 1876 by proclaiming a union with Bosnia. The Austrians and the other great powers preferred a weakened Ottoman empire to retain titular possession of Bosnia than to allow an upstart principality to claim it.

Serbia became a kingdom in 1882 under King Milan I. Milan had been adopted into the ruling Obrenović family after the death of his father in combat against the Ottomans. When Prince Mihailo Obrenović was assassinated in 1868, Milan was the eventual choice to succeed his adopted father. Milan remained king until he unexpectedly abdicated the throne in favour of his son Alexander in 1889. Despite having given up the throne, he returned to Serbia and eventually was appointed commander-in-chief of the Serbian army. He left that post in protest at his son’s marriage to Draga Mašin in 1900 and was banished for his pains. He died in 1901. King Alexander I did not long survive his father, being assassinated by members of an army conspiracy in 1903. The King had been ruling ever more harshly, creating much resentment through his arbitrary decrees and proclamations. The conspiracy was lead by Captain Dragutin Dimitrijević (nicknamed “Apis”), who would also later found the secret organization Ujedinjenje ili smrt! known as the Black Hand. The assassinations were so gory that Quentin Tarantino might have directed the scene if it was written by George R.R. Martin (as described by Christopher Clark):King Alexander and Queen Draga had no children and the Queen’s brother was widely assumed to be the heir-presumptive. Both of the queen’s brothers and several government officials were killed in the purge following the assassinations. These actions ended the Obrenović dynasty, as Alexander was succeeded by King Peter I, of the Karađorđević dynasty (Serbia had the misfortune of having two rival royal families from the early 1800’s to the assassination of Alexander I). King Peter’s father had been Prince of Serbia until his abdication in 1858, after which the family lived in exile. Under the pseudonym Pierre or Peter Kara, Peter had served as a junior officer on the French side in the Franco-Prussian War. Using a different pseudonym, he lead a guerilla unit against Ottoman troops in Bosnia and Herzegovina between 1875 and 1878. In 1883, he married the eldest daughter of the King of Montenegro. Through the connection between the royal families of Russia and Montenegro, two of his sons were enrolled in the Russian military academy.According to one account, the king, flabby, bespectacled and incongruously dressed in his red silk shirt, emerged with his arms around the queen. The couple were cut down in a hail of shots at point-blank range. Petrović [the king’s adjutant], who drew a concealed revolver in a final hopeless bid to protect his master (or so it was later claimed), was also killed. An orgy of gratuitous violence followed. The corpses were stabbed with swords, torn with a bayonet, partially dismembered and hacked with an axe until they were mutilated beyond recognition, according to the later testimony of the king’s traumatized Italian barber, who was ordered to collect the bodies and dress them for burial. The body of the queen was hoisted to the railing of the bedroom window and tossed, virtually naked and slimy with gore, into the gardens. It was reported that as the assassins attempted to do the same with Alexandar, one of his hands closed momentarily around the railing. An officer hacked through the fist with a sabre and the body fell, with a sprinkle of severed digits, to the earth. By the time the assassins had gathered in the gardens to have a smoke and inspect the results of their handiwork, it had begun to rain.

Whether through fear of suffering the same kind of violent death as his predecessor or through a genuine belief in liberalization, King Peter’s early reign was marked by a return to more democratic representation and parliamentary control of the government. The Austrian government had been on relatively good terms with the former king, and viewed the increasing democratization in Serbia as a dangerous trend (for fear it would give more impetus to demands for autonomy not only in Bosnia, but also in other Slavic areas of the empire). The Wikipedia entry for King Peter’s reign is just a tad over-enthusiastic:

The Western-educated King attempted to liberalize Serbia with the goal of creating a Western-style constitutional monarchy. King Petar I became gradually very popular for his commitment to parliamentary democracy that, in spite of certain influence of military cliques in political life, functioned properly. The 1903 Constitution was a revised version of 1888 Constitution, based on the Belgian Constitution of 1831, considered as one of the most liberal in Europe.The governments were chosen from the parliamentary majority, mostly from People’s Radical Party (Narodna radikalna stranka) led by Nikola P. Pašić and Independent Radical Party (Samostalna radikalna stranka), led by Ljubomir Stojanović. King Peter himself was in favor of a broader coalition government that would boost Serbian democracy and help pursue an independent course in foreign policy. In contrast to Austrophile Obrenović dynasty, King Peter I was relying on Russia and France, which provoked rising hostility from expansionist-minded Austria-Hungary. King Peter I of Serbia paid two solemn visits to Saint-Petersbourg and Paris in 1910 and 1911 respectively, greeted as a hero of both democracy and national independence in the troublesome Balkans.

The reign of King Peter I Karadjordjević from 1903 to 1914, is remembered as the “Golden Age of Serbia” or the “Era of Pericles in Serbia”, due to the unrestricted political freedoms, free press, and cultural ascendancy among South Slavs who finally saw in democratic Serbia a Piedmont of South Slavs. King Peter I was supportive to the movement of Yugoslav unification, hosting in Belgrade various cultural gatherings. Grand School of Belgrade was upgraded into Belgrade University in 1905, with scholars of international renown such as Jovan Cvijić, Mihailo Petrović, Slobodan Jovanović, Jovan M. Žujović, Bogdan Popović, Jovan Skerlić, Sima Lozanić, Branislav Petronijević and several others.

The Black Hand: Serbia’s “plausibly deniable” interference in Bosnian affairs

The leader of the 1903 coup d’etat, former Captain, now Colonel Dragutin “Apis” Dimitrijević was in a key position indeed — he was the head of the Serbian Military Intelligence service in 1914. From that important post, he was able to conduct covert operations against the neighbouring empires with an eye to destabilization and eventual military action. In 1911, Apis established Ujedinjenje ili smrt! (the Black Hand) to enable him to conduct operations separate from — but with goals aligned with — the formal state organization. Another semi-secret pan-Slavic organization set up a few years earlier became a very valuable tool in the hands of Apis: Mlada Bosna (Young Bosnia).

Margaret MacMillan in The War That Ended Peace describes the kind of operations “Apis” set up and operated against Austria-Hungary and the Ottomans:

Within Serbia itself there was considerable support for the Young Bosnians and their activities. For a decade or more, parts of the Serbian government had encouraged the activities of quasi-military and conspiratorial organizations on the soil of Serbia’s enemies, whether the Ottoman Empire or Austria-Hungary. The army provided money and weapons for armed Serbian bands in Macedonia and smuggled weapons into Bosnia much as Iran does today with Hezbollah in Lebanon.

Margaret MacMillan describes the typical members of the Young Bosnians, who were of a type that we probably recognize more readily now than at any time since 1914:

[They] were mostly young Serb and Croat peasant boys who had left the countryside to study and work in the towns and cities of the Dual Monarchy and Serbia. While they had put on suits in place of their traditional dress and condemned the conservatism of their elders, they nevertheless found much in the modern world bewildering and disturbing. It is hard not to compare them to the extreme groups among Islamic fundamentalists such as Al Qaeda a century later. Like those later fanatics, the Young Bosnians were usually fiercely puritanical, despising such things as alcohol and sexual intercourse. They hated Austria-Hungary in part because they blamed it for corrupting its South Slav subjects. Few of the Young Bosnians had regular jobs. Rather they depended on handouts from their families, with whom they had usually quarreled. They shared their few possessions, slept on each other’s floors, and spent hours over a single cup of coffee in cheap cafés arguing about life and politics. They were idealistic, and passionately committed to liberating Bosnia from foreign rule and to building a new and fairer world. Strongly influenced by the great Russian revolutionaries and anarchists, the Young Bosnians believed that they could only achieve their goals through violence and, if necessary, the sacrifice of their own lives.

Apis and his Bosnian operators were determined to take advantage of the announced visit by Archduke Franz Ferdinand to the Bosnian capital of Sarajevo in June, 1914. The Archduke was the heir-presumptive to the throne of the Dual Monarchy and (contrary to what a lot of people believed at the time) a moderate who hoped to use his visit to reduce tension between the monarchy and the Slavic people in the southern fringe of the empire. He had already spoken against the empire taking military action against Serbia on more than one occasion after provocation … if he were not on the scene, Apis calculated, the chances of war went up significantly.

The stage is set, the pieces are starting to fall into place, and the curtain is about to go up.

June 4, 2014

Sarcasm-detecting software wanted

Charles Stross discusses some of the second-order effects should the US Secret Service actually get the sarcasm-detection software they’re reportedly looking for:

… But then the Internet happened, and it just so happened to coincide with a flowering of highly politicized and canalized news media channels such that at any given time, whoever is POTUS, around 10% of the US population are convinced that they’re a baby-eating lizard-alien in a fleshsuit who is plotting to bring about the downfall of civilization, rather than a middle-aged male politician in a business suit.

Well now, here’s the thing: automating sarcasm detection is easy. It’s so easy they teach it in first year computer science courses; it’s an obvious application of AI. (You just get your Turing-test-passing AI that understands all the shared assumptions and social conventions that human-human conversation rely on to identify those statements that explicitly contradict beliefs that the conversationalist implicitly holds. So if I say “it’s easy to earn a living as a novelist” and the AI knows that most novelists don’t believe this and that I am a member of the set of all novelists, the AI can infer that I am being sarcastic. Or I’m an outlier. Or I’m trying to impress a date. Or I’m secretly plotting to assassinate the POTUS.)

Of course, we in the real world know that shaved apes like us never saw a system we didn’t want to game. So in the event that sarcasm detectors ever get a false positive rate of less than 99% (or a false negative rate of less than 1%) I predict that everybody will start deploying sarcasm as a standard conversational gambit on the internet.

Wait … I thought everyone already did?

Trolling the secret service will become a competitive sport, the goal being to not receive a visit from the SS in response to your totally serious threat to kill the resident of 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. Al Qaida terrrrst training camps will hold tutorials on metonymy, aggressive irony, cynical detachment, and sarcasm as a camouflage tactic for suicide bombers. Post-modernist pranks will draw down the full might of law enforcement by mistake, while actual death threats go encoded as LOLCat macros. Any attempt to algorithmically detect sarcasm will fail because sarcasm is self-referential and the awareness that a sarcasm detector may be in use will change the intent behind the message.

As the very first commenter points out, a problem with this is that a substantial proportion of software developers (as indicated by their position on the Asperger/Autism spectrum) find it very difficult to detect sarcasm in real life…

May 9, 2014

The 1964 trial of Jack Ruby

The Toronto Sun shares a portion of Peter Worthington’s Looking for Trouble (now available as an e-book) dealing with the trial of Jack Ruby. Worthington had been in the room when Ruby gunned down Lee Harvey Oswald.

The Ruby trial was pure showbiz. While the witnesses and characters who surfaced during the trial were Damon Runyon, the judge and lawyers seemed straight out of Al Capp and Dogpatch. Judge Joe B. Brown’s legal education before he was elected to the bench consisted of three years of night school 35 years earlier. In Dallas he was known as Necessity – “because Necessity knows no law.”

[…]

One day as a stripper who worked at Ruby’s nightclub called Little Lynn (who was over nine months pregnant at the time), was waiting to testify, seven prisoners in the connecting county jail grabbed a woman hostage and fled. They had fashioned a pistol of soap, pencils and shoe polish, persuaded guards that it was real, and made their break, witnessed by some 100 million viewers.

Little Lynn fainted and Belli prepared to play midwife. A BBC reporter on the phone to his office was describing the action and repeatedly swore to his editors that he was neither kidding, nor had he been drinking. “Listen, you bloody fools, this is America, this is Texas … any bloody insane thing is possible here!”

The next day, the New York Daily News ran an eloquent black headline: “Oh, Dallas!”

The jury returned in 140 minutes with a guilty verdict. In Texas, where the juries set the penalty, they opted for the electric chair.

Belli returned to San Francisco in disgust. “I shall never return here; it’s an evil, bigoted, rotten, stinking town.”

As it happened, Ruby died three years later and won a form of immortality and a place in criminal and political legend.

And as for conspiracy theories, the flaw is that Oswald was an ideologue, a semi-literate left-wing extremist, while Ruby wouldn’t know what an ideologue was unless he did a strip-tease for him.

To choose two such perfect foils on which to base a presidential murder plot challenges credulity. There has been so much official deceit, perjury, rationalization and cover-up that the deeds seem […] more sinister than they actually have been.

We will probably never know the truth.

November 22, 2013

“…you wonder why it took so long for somebody to shoot the swinish bastard”

Colby Cosh makes no friends among the over-60 Kennedy worshipping community:

The myth of Kennedy as a uniquely admirable knight-errant has finally, I think, been wiped out by the accumulation of ugly details about his sexual conduct and family life. For a while it was still possible to regard JFK’s tomcatting as the inevitable concomitant of super-masculine greatness. By now it is pretty clear that he was just an abusive, spoiled creep. There are scenes in White House intern Mimi Alford’s 2012 memoir that make you wonder why it took so long for somebody to shoot the swinish bastard.

As for the assassination itself, the experience of seeing conspiracy theories bloom like a toxic meadow after 9/11 has hardened us all against the nonsense that was still popular in the 1990s. Most adults, I think, now understand that Oliver Stone’s JFK was a buffet of tripe. It is no coincidence that Stephen King’s 2011 time-travel book about JFK’s slaying, written after decades of fairly deep research, stuck close to the orthodox Warren commission narrative.

The new favourite themes in the 50th anniversary coverage dispense with grassy-knoll phantoms and disappearing-reappearing Oswalds. One new documentary has revived Howard Donahue’s idea that the final bullet that blasted Kennedy’s skull apart might have been fired accidentally by a Secret Service agent in one of the trailing cars. This would help explain the oddity of the Zapruder footage, and might also account for some awkwardly disappearing evidence — notably JFK’s brain — without requiring us to believe anything obviously outrageous.

[…]

In the early ’70s Lyndon Johnson made a cryptic remark about JFK possibly being killed because his administration had been “running a damn Murder Inc. in the Caribbean.” This offhand remark turned out to be quite specific; rumours of multiple CIA assassination attempts against Castro were true, as were wilder tales of literal Mafia involvement (confirmed when the CIA “Family Jewels” were declassified in 2007). Oswald would not exactly have been anyone’s first choice as an intelligence asset, and probably had no state sponsor. But notice that it’s 2013 and we still have to say “probably.”