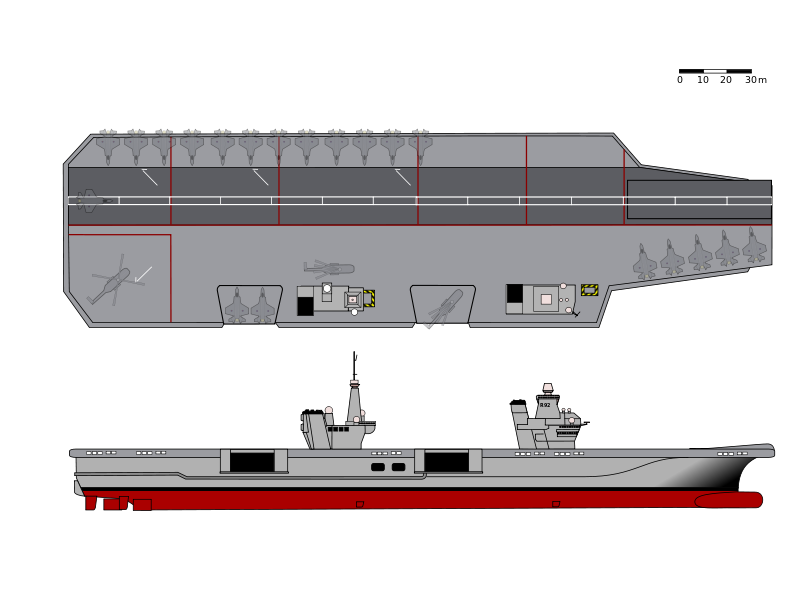

Last month, Save the Royal Navy looked at the aircraft that will fly off the decks of HMS Queen Elizabeth and HMS Prince of Wales:

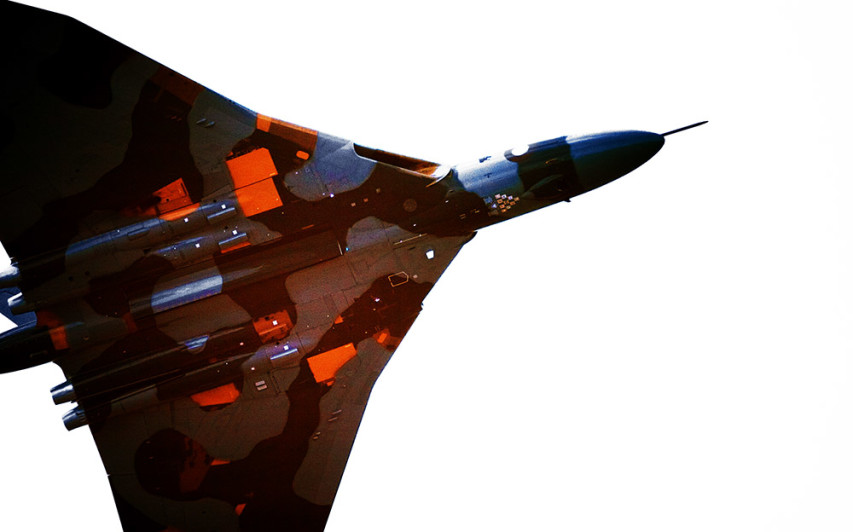

The SDSR stated that 42 F35-B Lightning aircraft will be delivered by 2023. These 42 aircraft form the carrier’s main armament. A foolish political fudge has given the RAF control of the Lightnings, to be jointly manned and operated with the RN. For Government, this conveniently boosts the RAF’s ORBAT while allowing the same aircraft to be counted again as part of the carrier’s equipment. Although the RAF may not like it, the needs of the carriers will have to dictate their operation. There is simply no place for the “part time carrier aviator” The aircrew need as much time at sea as possible to develop their own skills, the skills of aircraft handlers, the ship’s company and the fleet as a whole. Like all RN vessels the carriers will operate at a demanding operational tempo and need aircraft embarked for much of the time. Any RAF inclination to use the aircraft in the land-based deep strike role will have to be second priority.

The initial 42 Lightnings will be split between 2 frontline squadrons. 809 Naval Air Squadron and RAF 617 Squadron with around 15-20 aircraft each, building up to the full strength of 24 per squadron. There will also be a requirement for at least 5 aircraft to form an OCU (Operational Conversion Unit for training). An OEU (Operational Evaluation Unit for testing and trials) will also require a few aircraft. Allowing for a sustainment fleet of aircraft in deep maintenance etc, then it is clear that many more than 42 aircraft are needed to form just 2 full-strength squadrons. Between 2010 and 2014 the received wisdom was that the UK would only ever purchase a maximum of 48 F35-B but the SDSR announced a planned eventual purchase of as many as 138. This is good news which should give some strength-in-depth, potentially providing 2 more squadrons. Both the RN and the RAF should be able to fulfil their ambitions for the Lighting. Whether the RAF will push for a purchase of the conventional F35-A which would not be compatible with the carrier, but has slightly better range and performance than the VSTOL variant is a discussion for the future.

Of course the caveat to all this good news is the actual performance of the F35. There are armies of armchair F-35 critics and many of their concerns are valid. Although it may prove to be a poor “within visual range” fighter, its networking, sensors, stealth and strike capabilities will be a giant advance over any previous UK military aircraft. Furthermore the RN has a fine track record of taking equipment with many apparent deficiencies and turning them into a great success. (Fairy Swordfish anyone?)

On the other hand, Ben Ho Wan Beng argues that the carriers will not actually be able to project much power:

A tactical combat aircraft complement of 12, or even 15-20, is rather small for traditional carrier operations, especially force-projection ones that are likely to predominate considering the SDSR’s expeditionary-warfare slant. Indeed, it is worth considering the fact that the two British small-deck carriers involved in the Falklands War carried 20-odd Harrier jump jets each, and they were about three times smaller than the Queen Elizabeth-class ships.

In fact, each new carrier might even be operating with a much fighter complement fewer than 15-20 in the years leading up to 2023, giving lie to the phrase “in force” used by George Osborne when he spoke of equipping the carriers with significant airpower.

In any case, the small fighter constituent means that if the Queen Elizabeth carrier were to get involved in a conflict with an adversary with credible anti-access/area-denial (A2/AD) capabilities, the vessel would be hard-pressed to protect itself, let alone project power. With a displacement of over 70,000 tons and costing over three billion pounds each, the new British carriers will be the crown jewels of the Royal Navy; indeed, HMS Queen Elizabeth is slated to be the RN’s flagship when she comes into service. The protection of the ship would hence be of paramount importance in an era that has witnessed the proliferation of A2/AD capabilities even to developing nations. Hence for a Queen Elizabeth carrying 20 or less Lightnings in such circumstances, it remains to be seen just how many of the aircraft will be earmarked for different duties.

Should a F-35B air group of that size put to sea, at least half of them will be assigned to the Combat Air Patrol (CAP), leaving barely 10 for offensive duties. It is worth noting that of the 42 Harrier VSTOL jets deployed on HMS Hermes and HMS Invincible during the Falklands War, 28 of them – a substantial two-thirds – had CAP as their primary duty. It is also telling that of the 1,300-odd sorties flown in all by the Harriers, about 83 per cent of them were for CAP.

Faced with modern A2/AD systems such as stand-off anti-ship missiles, how likely then would the carrier task force commander devote more resources to offense and risk having a vessel named after British royalty attacked and hit? Having said that, having too many planes for defense strengthens the argument made by various carrier critics that the ship is a “self-licking ice cream cone,” in other words, an entity that exists solely to sustain itself.

The task force commander would thus be caught between a rock and a hard place. Allocate more F-35Bs to strike missions and the susceptibility of the task force to aerial threats increase. Conversely, set aside more aircraft for the CAP and its mother ship’s ability to project power decreases. All in all, with a significantly understrength F-35B air wing, the Queen Elizabeth flat-top would be operating under severe constraints, making it incapable of the traditional carrier operations it could have carried out with a larger tactical aircraft complement. Indeed, one naval commentator is right on the mark when he argues that two squadrons with a total of 24 aircraft should be a “sensible minimum standard” for each carrier.