Well, perhaps you say, that is a bit simplistic; what if we go on a strategic defensive – adopting a strategy of attrition? Note we are fairly far now from the idea that the easy solution to trench warfare was “don’t attack”, but this is the first time we reach what appears on its face to be a workable strategy: accept that this is a pure war of attrition and thus attempt to win the attrition.

And here is where I, the frustrated historian, let out the primal cry: “They did that! Those ‘idiot’ generals you were bashing on a moment ago did exactly this thing, they did it in 1916 and it didn’t work.”

As Robert Doughty (op. cit.) notes quite effectively, after the desperate search in 1915 for ways either around the trench stalemate or through it (either way trying to restore a war of maneuver), Joseph Joffre, French chief of the army staff, settled on a strategic plan coordinating British, Italian, French and Russian actions designed around a strategy of “rupture” by which what was meant was that if all of the allies focused on attrition in each of their various theaters, eventually one theater would break for lack of resources (that’s the rupture). He was pretty damn explicit about this, writing about the war as a “struggle of attrition” in May, 1915 and setting a plan of action in December of 1915 to “do everything they can to attrit the adversary”.

Joffre’s plan did not go perfectly (the German offensive at Verdun upset the time-tables) but it did, in fact mean lower French losses in 1916 than in 1915 or 1914 and more severe German losses. Meanwhile, the German commander, Erich von Falkenhayn would at least subsequently claim to have been trying to do the same thing: achieve favorable casualty ratios in a war of attrition, with his set piece being the Battle of Verdun, designed to draw the French into bloody and useless repeated counter-attacks on ground that favored the Germans (there remains a lot of argument and uncertainty as to if that attritional strategy was the original plan, or merely Falkenhayn’s excuse for the failure to achieve meaningful strategic objectives at Verdun). In the end, the Verdun strategy, if that was the strategy, failed because while the Germans could get their favorable ratio on the attack, it slipped away from them in the inevitable French counter-attacks.

But as Clausewitz reminds us (drink!) will – both political and popular – is a factor in war too (indeed, it is one of the factors as part of the Clausewitzian trinity!). Both Joffre and Falkenhayn had to an extent seen that the war was going to run until one side ran out of soldiers and material and aimed to win that long, gruelling war; for which they were both promptly fired! The solution to the war which said that all one needed to do was sacrifice a few more million soldiers and wait 2, or perhaps 3 or maybe even 4 more years for the enemy to run out first was unacceptable to either the political leaders or the public. 1917 came around and both sides entrusted the war to generals who claimed to be able to produce victories faster than that: to Robert Nivelle and Erich Ludendorff, with their plans of bold offensives.

And to be clear, from a pure perspective of “how do we win the war” that political calculation is not entirely wrong. Going to the public, asking them to send their sons to fight, to endure more rationing, more shortages, more long casualty lists with the explanation that you had no plans to win the war beyond running Germany out of sons slightly faster than you ran France out of sons would have led to the collapse of public morale (and subsequent defeat). Telling your army that would hardly be good for their morale either (the French army would mutiny in 1917 in any event). Remember that in each battle, casualties were high on both sides so there was no avoiding that adopting an attrition strategy towards the enemy meant also accepting that same attrition on your own troops.

And, as we’ve discussed endlessly, morale matters in war! “Wait for the British blockade to win the war by starving millions of central Europeans to death” was probably, in a cold calculus, the best strategy (after the true winning strategy of “don’t have a World War I”), but it was also, from a political perspective, an unworkable one. And a strategy which is the best except for being politically unworkable is not the best because generals must operate in the real world, not in a war game where they may cheerfully disregard questions of will. In short, both sides attempted a strategy of pure attrition on the Western Front and in both cases, the strategy exhausted political will years before it could have borne fruit.

And so none of these easy solutions work; in most cases (except for “recruit a lost Greek demi-god”) they were actually tried and failed either due to the dynamics (or perhaps, more truthfully, the statics) of trench warfare or because they proved impossible implement from a morale-and-politics perspective, violating the fundamental human need to see an end to the war that didn’t involve getting nearly everyone killed first.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: No Man’s Land, Part I: The Trench Stalemate”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-09-17.

July 24, 2024

QotD: The “strategic defensive” approach to the attrition battles of WW1

July 14, 2024

Britain’s First Naval Defeat in 100 years – Coronel 1914

Historigraph

Published Sep 26, 2020

July 10, 2024

Two World Wars: Finnish C96 “Ukko-Mauser”

Forgotten Weapons

Published Mar 27, 2024A decent number of C96 Mauser pistols were present in Finland’s civil war, many of them coming into the country with the Finnish Jaegers, and others from a variety of sources, commercial and Russian. They were used by both the Reds and the Whites, and in both 9x19mm and 7.63x25mm. After the end of the civil war, when the military was standardizing, the C96s were handed over to the Civil Guard, where they generally remained until recalled to army inventories in 1939. They once again saw service in the Winter War and Continuation War, and went into military stores afterwards until eventually being surplussed as obsolete.

One of the interesting aspects of Finnish C96s is that many of them come from the so-called “Scandinavian Contract” batch (for which no contract has actually turned up). These appear to be guns made in 7.63mm that were numbered as part of the early production in the Prussian “Red 9” series, probably for delivery to specific German units or partner forces during World War One.

(more…)

July 6, 2024

Why Germany Lost the Battle of Verdun

The Great War

Published Mar 8, 2024The Battle of Verdun represents the worst of trench warfare and the suffering of the soldiers in the minds of millions – and for many, the cruel futility of the First World War. But why did Germany decide to attack Verdun in the first place and why didn’t they stop after their initial attack failed?

(more…)

July 4, 2024

How the First Tanks CONQUERED the Trenches

The Tank Museum

Published Mar 16, 2024This is the story of the evolution of the tank during World War One. Notorious for its appalling human cost, the First World War was fought using the latest technology – and the tank was invented to overcome the brutally unique conditions of this conflict.

Arriving at the mid-point of the war, they would be built and used by the British Commonwealth, French and German armies – with the US Army using both British and French designs.

00:00 | Intro

01:17 | The Beginnings of WWI

02:13 | The Solution to Trench Warfare

03:47 | Initial Ideas

05:42 | How to Cross a Trench

08:08 | How Effective was the Tank?

15:40 | Battlefield Upgrades

17:09 | New Designs

24:32 | ConclusionThis video features archive footage courtesy of British Pathé.

#tankmuseum #evolution #tank #tanks #ww1 #technology

June 26, 2024

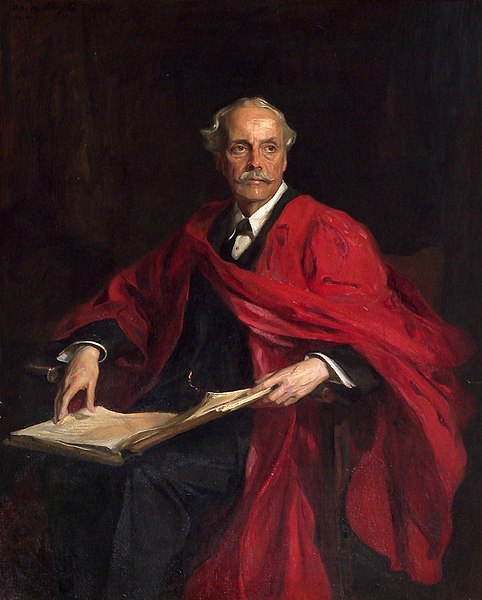

Lord Balfour

Arthur Lord Balfour, Conservative Prime Minister from 1902 to 1905, is perhaps best known for the Balfour Declaration issued during World War 1 that established the formal goal of an independent homeland for the Jews in the Holy Land. Who was he? Barbara Kay’s essay originally published in the Dorchester Review was recently reposted at Woke Watch Canada:

“Arthur James Balfour, 1st Earl of Balfour, KG, OM, PC, Prime Minister and Philosopher” portrait in oil by Philip de László, 1914.

From the Trinity College collection via Wikimedia Commons.

Why was the aristocrat Lord Balfour, the social antithesis of this humble Jew from the Pale of Russia, so taken with Weizmann’s vision that he was willing to expend political capital and exert so much effort to see it realized? Who was Balfour? What was he?

Arthur James Balfour was born at his family seat, Whittingehame, in East Lothian, the “granary of Scotland”. A forebear had made a fortune in India in military materials, so he was financially secure for life, and socially connected at the highest levels.

Having lost his father when he was 7, Balfour was lucky in his mother, a strong-willed and educated woman who, according to Mrs Dugdale, inculcated the idea of duty as “the uncompromising foundation of his character”. He attended Eton and Cambridge, where he was described by a friend as “a man of unusual philosophy and metaphysics”, who could hold his own with the Dons (professors), “some of them men of undoubted genius”. He was devoted to his extended family, and much beloved by his nieces and nephews.

In his essay “Arthur Balfour: a Fatal Charm”1 cultural critic Ferdinand Mount cites “nonchalance” as Balfour’s defining trait. Legendarily indolent, he rarely rose before 11 a.m., claimed never to read newspapers, and disdained the ritual schmoozing of fellow backbenchers expected by his peers in the Members’ Smoking Room. Mount says he was “indifferent to what his colleagues, the public or posterity thought of him or his policies”.

This loftiness — echoed in his unusual physical height — was perceived as admirable or maddening according to the observer and circumstances. Churchill said of him: “He was quite fearless. When they took him to the Front to see the war, he admired the bursting shells blandly through his pince-nez. There was in fact no way of getting to him.”

His self-sufficiency was no act. Sports-mad, he skipped lunch with the Kaiser to watch the Eton and Harrow cricket match, and when in Scotland might play two full rounds of golf a day (his handicap of 10 was better than P. G. Wodehouse and about the same as thriller writer Ian Fleming’s).

Balfour sounds from my description so far as if he was something of a playboy, but that is a very partial portrait. He was also known as “Bloody Balfour” for his readiness to endorse police action and his apparent indifference to their cost.

The Irish loathed him. In 1887 he became personal secretary for Ireland under his uncle, Lord Salisbury, just in time to enforce the Coercion Act against the volatile Irish Land League. Indeed, Balfour’s parliamentary critic William O’Brien saw him as a man who harboured a “lust for slaughter with a eunuchized imagination” who took “a strange pleasure in mere purposeless human suffering, which imparted a delicious excitement to his languid life”.

One hopes this accusation of actual sadism is an exaggeration of Balfour’s indubitable detachment. Yet indifference to human life is certainly not an uncommon charge laid against intellectuals for whom ideas loom larger in their claims to attention than the fate of those beyond their particular tribes.

For balance, we have Barbara Tuchman’s assessment:

Balfour had a capacious and philosophical mind. Words to describe him by contemporaries are often “charm” and “cynicism”. He had a profound and philosophic mind, he was lazy, imperturbable in any fracas, shunned detail, left facts to subordinates, played tennis whenever possible, but pursued his principles of statecraft with every art of politics under the command of a superb intelligence.

Fortunately for his temperament, Balfour’s life circumstances had landed him at the centre of a genuinely intellectual circle. His brothers in-law, for example, were Lord Rayleigh, who became head of the Cambridge Laboratory and won the Nobel Prize for Physics, and Henry Sidgwick, the Cambridge philosopher who with his wife Elaine Balfour founded Newnham College.

Politically, Balfour enjoyed both dramatic success and dramatic failure. He led the Unionist Party longer than anyone before him since Pitt the Younger. And he was a minister longer than anyone else in the 20th century, including Winston Churchill. Balfour was the only Unionist who was invited to join Asquith’s first war cabinet, and continued as foreign secretary after the coup that brought Lloyd George to power.

As Churchill put it: “He passed from one cabinet to the other, from the prime minister who was his champion to the prime minister who had been his most severe critic, like a powerful, graceful cat walking delicately and unsoiled across a rather muddy street”.

One of Balfour’s teachers at Eton described him as “fearless, resolved and negligently great”. On the other hand, Mount tells us, “indecisiveness” was his bane. He would stand paralyzed in the mezzanine of his London home agonizing over which of the matching staircases to descend by. He could love — the great love of his life died after an unreasonably long engagement — but, allegedly too staggered by the loss of his almost-fiancée, he never married.2 He could not be pinned down politically on many issues, a matter of great frustration to his colleagues, and this cost him dearly. As Mount notes, his charm was indisputable, “but more than charm he would not give” and “in the end, the charm is all that remains.”

Balfour fought three general elections as party leader and lost them all. His premiership lasted less than four years and ended in a Liberal landslide in 2006, a great electoral humiliation in making him the only prime minister in the 20th century to lose his own seat. He did not seem greatly to repine at the rejection, though, and it is thanks to the loss that he had time to further his education on the Zionist movement.

1. Mount, Ferdinand, English Voices (2016), pp 358 ff.

2. One suspects that even if May Lyttleton had lived, Balfour would have avoided marrying her on some pretext or other. There is no evidence that Balfour was a closeted homosexual, but he may have been asexual. He enjoyed an “amitié amoureuse” with (married) Mary Elcho for 30 years involving little or nothing in the way of sex, after which she wrote to him, “I’ll give you this much, tho, for although you have only loved me little, yet I must admit you have loved me long”.

June 9, 2024

Men In Armour (1949) – The origins and operation of tanks

FWD Publishing

Published Feb 18, 2024Lengthy documentary made in 1949 about the men and tanks of the Royal Armoured Corps (RAC).

June 6, 2024

QotD: Herbert Hoover as Woodrow Wilson’s “Food Dictator”

In 1917, America enters World War I. Hoover […] returns to the US a war hero. The New York Times proclaims Hoover’s CRB work “the greatest American achievement of the last two years”. There is talk that he should run for President. Instead, he goes to Washington and tells President Woodrow Wilson he is at his service.

Wilson is working on the greatest mobilization in American history. He realizes one of the US’ most important roles will be breadbasket for the Allied Powers, and names Hoover “food commissioner”, in charge of ensuring that there is enough food to support the troops, the home front, and the other Allies. His powers are absurdly vast – he can do anything at all related to the nation’s food supply, from fixing prices to confiscating shipments from telling families what to eat. The press affectionately dubs him “Food Dictator” (I assume today they would use “Food Czar”, but this is 1917 and it is Too Soon).

Hoover displays the same manic energy he showed in Belgium. His public relations blitz telling families to save food is so successful that the word “Hooverize” enters the language, meaning to ration or consume efficiently. But it turns out none of this is necessary. Hoover improves food production and distribution efficiency so much that no rationing is needed, America has lots of food to export to Europe, and his rationing agency makes an eight-digit profit selling all the extra food it has.

By 1918, Europe is in ruins. The warring powers have declared an Armistice, but their people are starving, and winter is coming on fast. Also, Herbert Hoover has so much food that he has to swim through amber waves of grain to get to work every morning. Mountains of uneaten pork bellies are starting to blot out the sky. Maybe one of these problems can solve the other? President Wilson dispatches Hoover to Europe as “special representative for relief and economic rehabilitation”. Hoover rises to the challenge:

Hoover accepted the assignment with the usual claim that he had no interest in the job, simultaneously seeking for himself the broadest possible mandate and absolute control. The broad mandate, he said, was essential, because he could not hope to deliver food without refurnishing Europe’s broken finance, trade, communications, and transportation systems …

Hoover had a hundred ships filled with food bound for neutral and newly liberated parts of the Continent before the peace conferences were even underway. He formalized his power in January 1919 by drafting for Wilson a post facto executive order authorizing the creation of the American Relief Administration (ARA), with Hoover as its executive director, authorized to feed Europe by practically any means he deemed necessary. He addressed the order to himself and passed it to the president for his signature …

The actual delivery of relief was ingeniously improvised. Only Hoover, with his keen grasp of the mechanics of civilization, could have made the logistics of rehabilitating a war-ravaged continent look easy. He arranged to extend the tours of thousands of US Army officers already on the scene and deployed them as ARA agents in 32 different countries. Finding Europe’s telegraph and telephone services a shambles, he used US Navy vessels and Army Signal Corps employees to devise the best-functioning and most secure wireless system on the continent. Needing transportation, Hoover took charge of ports and canals and rebuilt railroads in Central and Eastern Europe. The ARA was for a time the only agency that could reliably arrange shipping between nations …

The New York Times said it was only apparent in retrospect how much power Hoover wielded during the peace talks. “He has been the nearest approach Europe has had to a dictator since Napoleon.”

Once again, Hoover faces not only the inherent challenge of feeding millions, but opposition from the national governments he is trying to serve. Britain and France plan to let Germany starve, hoping this will decrease its bargaining power at Versailles. They ban Hoover from transporting any food to the defeated Central Powers. Hoover, “in a series of transactions so byzantine it was impossible for outsiders to see exactly what he was up to”, causes some kind of absurd logistics chain that results in 42% of the food getting to Germany in untraceable ways.

He is less able to stop the European powers’ controlled implosion at Versailles. He believes 100% in Woodrow Wilson’s vision of a fair peace treaty with no reparations for Germany and a League Of Nations powerful enough to prevent any future wars. But Wilson and Hoover famously fail. Hoover predicts a second World War in five years (later he lowers his estimate to “thirty days”), but takes comfort in what he has been able to accomplish thus far.

He returns to the US as some sort of super-double-war-hero. He is credited with saving tens of millions of lives, keeping Europe from fraying apart, and preventing the spread of Communism. He is not just a saint but a magician, accomplishing feats of logistics that everyone believed impossible. John Maynard Keynes:

Never was a nobler work of disinterested goodwill carried through with more tenacy and sincerity and skill, and with less thanks either asked or given. The ungrateful Governments of Europe owe much more to the statesmanship and insight of Mr. Hoover and his band of American workers than they have yet appreciated or will ever acknowledge. It was their efforts … often acting in the teeth of European obstruction, which not only saved an immense amount of human suffering, but averted a widespread breakdown of the European system.

Scott Alexander, “Book Review: Hoover”, Slate Star Codex, 2020-03-17.

June 4, 2024

Snipers in World War 1

The Great War

Published Feb 9, 2024In fall 1914, the British and French armies on the First World War’s Western Front were wrestling with a problem: unseen German riflemen were picking off any man who showed himself above the trench. Something had to be done about it – and the result was the birth of the modern sniper.

(more…)

June 1, 2024

I plead the Pith: a History of the Pith Helmet

HatHistorian

Published Jun 1, 2022A symbol of exploration, tropical adventure, and colonialism, the pith helmet has had a long history since its origins as the salakot, a Philippine sun hat. Through many iterations, it had become one of the most famous hats out there, a powerful part of popular imagination.

The helmets I wear in this video come respectively from a gift from a family friend (so I don’t know where it was bought, https://www.historicalemporium.com/, and Amazon.com. The red tunic comes from thehistorybunker.co.uk

Title sequence designed by Alexandre Mahler

am.design@live.comThis video was done for entertainment and educational purposes. No copyright infringement of any sort was intended.

May 9, 2024

How the First World War Created the Middle East Conflicts

The Great War

Published Dec 8, 2023The modern Middle East is a region troubled by war, terrorism, weak and failed states, and civil unrest. But how did it get this way? The map of today’s Middle East was mostly drawn after the First World War, and the war that planted many of the seeds of conflict that still plague Israel, Palestine, Iraq, Syria and even Iran today.

(more…)

April 17, 2024

French M14 Conversion – the Gras in 8mm Lebel

Forgotten Weapons

Published May 16, 2016The French adopted the Gras as their first mass-issued metallic cartridge rifle in 1874, replacing the needlefire 1866 Chassepot. Quite a lot of Gras rifles were manufactured, and they became a second-line rifle when the 1886 Lebel was introduced with brand-new smokeless powder and its smallbore 8mm projectile. When it became clear that the quick and decisive war against Germany was truly turning into the Great War, France began looking for ways to increase the number of modern Lebel rifles it could supply to the front.

One option that was used was to take Gras rifles from inventory and rebarrel them for the 8mm Lebel cartridge (which was based on the Gras casehead anyway). These could be issued to troops who didn’t really need a top-of-the-line rifle (like artillery crews, train and prison guards, etc). Then the Lebel rifles from those troops could be redirected to the front.

The rebarreling process was done by a number of contractors, using Lebel barrels already in mass production. The 11mm barrel from the Gras would be removed, and only the front 6 inches (150mm) or so kept. A Lebel barrel and rear sight would be mounted on the Gras receiver, and that front 6 inches of Gras barrel bored out to fit tightly over the muzzle of the new 8mm barrel. This allowed the original stock and nosecap to be used (the 8mm barrel being substantially smaller in diameter, and not fitting the stock and hardware by itself). It also allowed the original Gras bayonet to be fitted without modification, since the bayonet lug was also on that retained section of barrel. In addition, a short wooden handguard was fitted. This was designated the modification of 1914, and an “M14” was stamped on the receivers to note it.

These guns are of dubious safety to shoot, since the retain the single locking lug of the Gras, designed for only black powder pressures. However, this was deemed safe enough for the small amount of actual shooting they were expected to do.

February 29, 2024

Hotchkiss Portative: Clunky But Durable

Forgotten Weapons

Published Nov 27, 2023The Portative was an attempt by the Hotchkiss company to make a light machine gun companion to their heavy model (which had found significant commercial success). The Portative used the same feed strips, albeit loaded upside down, and the same gas piston operation, but a very different locking system. Instead of a tilting locking block the Portative had a “fermeture nut” that rotated to lock onto the bolt with three sets of interrupted thread locking lugs. In addition, many of the traditionally internal parts were mounted externally on the Portative, and it was quite the awkward gun to use.

The Portative was adopted by the American Army as the Model 1909 Benet-Mercié, and by the British early in World War One as a cavalry and tank-mounted gun. The remainder of Portative contracts were relatively small from second-tier military forces, including several South American countries.

(more…)

February 28, 2024

Why Germany Lost the First World War

The Great War

Published Nov 10, 2023Germany’s defeat in the First World War has been blamed on all kinds of factors or has even been denied outright as part of the “stab in the back” myth. But why did Germany actually lose?

(more…)

February 21, 2024

Can you make a tank disappear? The Evolution of Tank Camouflage

The Tank Museum

Published Nov 17, 2023It’s not easy to hide a tank. But over the years, military commanders have developed ways to disguise, cover and conceal the presence of their tanks from the enemy. This video is about the “art of deception” – and how, since World War One, through World War Two and into the present day, the science of tank camouflage has evolved to meet the conditions and threats of the contemporary battlefield.

00:00 | Intro

01:38 | WWI

06:26 | WW2

13:42 | Post War

19:40 | Conclusion

(more…)