I think it was at the 1983 Usenix/UniForum conference (there is an outside possibility that I’m off by a year and it was ’84, which I will ignore in the remainder of this report). I was just a random young programmer then, sent to the conference as a reward by the company for which I was the house Unix guru at the time (my last regular job). More or less by chance, I walked into the meeting where the leaders of IETF were meeting to finalize the design of Internet DNS.

When I walked in, the crowd in that room was all set to approve a policy architecture that would have abolished the functional domains (.com, .net, .org, .mil, .gov) in favor of a purely geographic system. There’d be a .us domain, state-level ones under that, city and county and municipal ones under that, and hostnames some levels down. All very tidy and predictable, but I saw a problem.

I raised a hand tentatively. “Um,” I said, “what happens when people move?”

There was a long, stunned pause. Then a very polite but intense argument broke out. Most of the room on one side, me and one other guy on the other.

OK, I can see you boggling out there, you in your world of laptops and smartphones and WiFi. You take for granted that computers are mobile. You may have one in your pocket right now. Dude, it was 1983. 1983. The personal computers of the day barely existed; they were primitive toys that serious programmers mostly looked down on, and not without reason. Connecting them to the nascent Internet would have been ludicrous, impossible; they lacked the processing power to handle it even if the hardware had existed, which it didn’t yet. Mainframes and minicomputers ruled the earth, stolidly immobile in glass-fronted rooms with raised floors.

So no, it wasn’t crazy that the entire top echelon of IETF could be blindsided with that question by a twentysomething smartaleck kid who happened to have bought one of the first three IBM PCs to reach the East Coast. The gist of my argument was that (a) people were gonna move, and (b) because we didn’t really know what the future would be like, we should be prescribing as much mechanism and as little policy as we could. That is, we shouldn’t try to kill off the functional domains, we should allow both functional and geographical ones to coexist and let the market sort out what it wanted. To their eternal credit, they didn’t kick me out of the room for being an asshole when I actually declaimed the phrase “Let a thousand flowers bloom!”.

[…]

The majority counter, at first, was basically “But that would be chaos!” They were right, of course. But I was right too. The logic of my position was unassailable, really, and people started coming around fairly quickly. It was all done in less than 90 minutes. And that’s why I like to joke that the domain-name gold rush and the ensuing bumptious anarchy in the Internet’s host-naming system is all my fault.

It’s not true, really. It isn’t enough that my argument was correct on the merits; for the outcome we got, the IETF had to be willing to let a n00b who’d never been part of their process upset their conceptual applecart at a meeting that I think was supposed to be mainly a formality ratifying decisions that had already been made in working papers. I give them much more credit for that than I’ll ever claim for being the n00b in question, and I’ve emphasized that every time I’ve told this story.

Eric S. Raymond, “Eminent Domains: The First Time I Changed History”, Armed and Dangerous, 2010-09-11.

October 10, 2018

QotD: The first time ESR changed the world

October 8, 2018

Enzo Ferrari – Tank Sounds – French-American Animosity I OUT OF THE TRENCHES

The Great War

Published on 6 Oct 2018Chair of Wisdom Time!

QotD: The closed-source software dystopia we barely avoided

Thought experiment: imagine a future in which everybody takes for granted that all software outside a few toy projects in academia will be closed source controlled by managerial elites, computers are unhackable sealed boxes, communications protocols are opaque and locked down, and any use of computer-assisted technology requires layers of permissions that (in effect) mean digital information flow is utterly controlled by those with political and legal master keys. What kind of society do you suppose eventually issues from that?

Remember Trusted Computing and Palladium and crypto-export restrictions? RMS and Linus Torvalds and John Gilmore and I and a few score other hackers aborted that future before it was born, by using our leverage as engineers and mentors of engineers to change the ground of debate. The entire hacker culture at the time was certainly less than 5% of the population, by orders of magnitude.

And we may have mainstreamed open source just in time. In an attempt to defend their failing business model, the MPAA/RIAA axis of evil spent years pushing for digital “rights” management so pervasively baked into personal-computer hardware by regulatory fiat that those would have become unhackable. Large closed-source software producers had no problem with this, as it would have scratched their backs too. In retrospect, I think it was only the creation of a pro-open-source constituency with lots of money and political clout that prevented this.

Did we bend the trajectory of society? Yes. Yes, I think we did. It wasn’t a given that we’d get a future in which any random person could have a website and a blog, you know. It wasn’t even given that we’d have an Internet that anyone could hook up to without permission. And I’m pretty sure that if the political class had understood the implications of what we were actually doing, they’d have insisted on more centralized control. ~For the public good and the children, don’t you know.~

So, yes, sometimes very tiny groups can change society in visibly large ways on a short timescale. I’ve been there when it was done; once or twice I’ve been the instrument of change myself.

Eric S. Raymond, “Engineering history”, Armed and Dangerous, 2010-09-12.

October 4, 2018

Prairie Gun Works Timberwolf: British Trials Sniper Rifle

Forgotten Weapons

Published on 26 Sep 2017Armament Research Services (ARES) is a specialist technical intelligence consultancy, offering expertise and analysis to a range of government and non-government entities in the arms and munitions field. For detailed photos of the guns in this video, don’t miss the ARES companion blog post:

http://armamentresearch.com/north-ame…

The Timberwolf is a bolt action precision rifle made by Prairie Gun Works of Manitoba, Canada. It was initially made as a commercial rifle in a number of different calibers, and in 2001 it won Canadian trials to become the C14 Timberwolf Medium Range Sniper Weapon System (replacing the C3A1 Parker-Hale 7.62 NATO rifle previously used in that role).

The Timberwolf was also tested by the British military, and the one we have in today’s video (courtesy of the Shrivenham Defense Academy) is serial number UK001; the British trials rifle. It was not adopted, and the British opted to continue using Accuracy International bolt action rifles for its snipers.

In both the Canadian issue configuration and the British trials version, the rifle is chambered for the .338 Lapua Magnum cartridge, allowing a longer supersonic range than 7.62mm NATO.

http://www.patreon.com/ForgottenWeapons

If you enjoy Forgotten Weapons, check out its sister channel, InRangeTV! http://www.youtube.com/InRangeTVShow

October 3, 2018

The Uzi Submachine Gun: Excellent or Overrated?

Forgotten Weapons

Published on 5 Mar 2018The Israeli Uzi has become a truly iconic submachine gun through both its military use and its Hollywood stunts – but how effective is it really?

I found this fully automatic Uzi Model A to be actually rather better than I had expected. Despite the uncomfortable sharp metal stock, the rate of fire and large sights make this a relatively easy gun to shoot. Not one of the absolute best, but certainly above average.

http://www.patreon.com/ForgottenWeapons

If you enjoy Forgotten Weapons, check out its sister channel, InRangeTV! http://www.youtube.com/InRangeTVShow

October 1, 2018

Machine Guns Of World War 1 I THE GREAT WAR Special feat. C&Rsenal

The Great War

Published on 29 Sep 2018Support Othais on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/CandRsenal

Indy and Othais talk about the different kinds of machine guns that were used during World War 1.

QotD: The idiocy of “solar roads”

First, solar roads are a terrible idea. Even if they can be made to sort of work, the cost per KwH has to be higher than for solar panels in a more traditional installations — the panels are more expensive because they have to be hardened for traffic, and their production will be lower due to dirt and shade and the fact that they can’t be angled to the optimal pitch to catch the most sun. Plus, because the whole road has to be blocked (creating traffic snafus) just to fix one panel, it is far more likely that dead panels will just be left in place rather than replaced.

And who in their right mind would ever accept the statement that the solar panel roads would be cheaper to fix than a roadway? What agency anywhere takes out whole patches of road to fix small cracks? Square foot for square foot a solar road would be orders of magnitude harder to fix than just patching a pothole somewhere.

I love the line about “ideally” paying for themselves. I am sure this is their ideal, but what is the reality? I will bet anyone a million dollars that if all installation and maintenance costs are included, these will not come close to paying for themselves. The first rule of alternate energy in any news article is to give the installation cost or the energy output, but never both, so actual return on investment can’t be calculated. If they give neither, as in this case, it really sucks.

And finally, what is not to love about the last paragraph, which says effectively that roads should be as smart as the cars that drive on them. I have toyed with the idea of creating a whole new blog category on things people say that get millennials excited but make absolutely no sense. This would be a good example. Embedding solar panels in a road when just about any other flat surface anywhere would be a better place to put them is not “smart”, it is painfully stupid. A smart road might embed guide wires or some other technology to aid self-driving cars, but nothing like this.

Warren Meyer, “The Terrible Idea That Won’t Die: Solar Roads”, Coyote Blog, 2016-07-06.

September 27, 2018

Mind Your Business #4: Free the Unikrn

Foundation for Economic Education

Published on 25 Sep 2018Forget about slot machines, the future of gaming is virtual reality! In this episode of Mind Your Business, Andrew Heaton is teaming up with entrepreneur Rahul Sood to learn all about esports, safe and legal online betting, and the global community that is surging behind organized competitive video gaming.

September 24, 2018

Verity Stob on early GUI experiences

“Verity Stob” began writing about technology issues three decades back. She reminisces about some things that have changed and others that are still irritatingly the same:

It’s 30 years since .EXE Magazine carried the first Stob column; this is its

pearlPerl anniversary. Rereading article #1, a spoof self-tester in the Cosmo style, I was struck by how distant the world it invoked seemed. For example:

Your program requires a disk to have been put in the floppy drive, but it hasn’t. What happens next?

The original answers, such as:

e) the program crashes out into DOS, leaving dozens of files open

would now need to be supplemented by

f) what’s ‘the floppy drive’ already, Grandma? And while you’re at it, what is DOS? Part of some sort of DOS and DON’TS list?

I say: sufficient excuse to present some Then and Now comparisons with those primordial days of programming, to show how much things have changed – or not.

1988: Drag-and-drop was a showy-offy but not-quite-satisfactory technology.

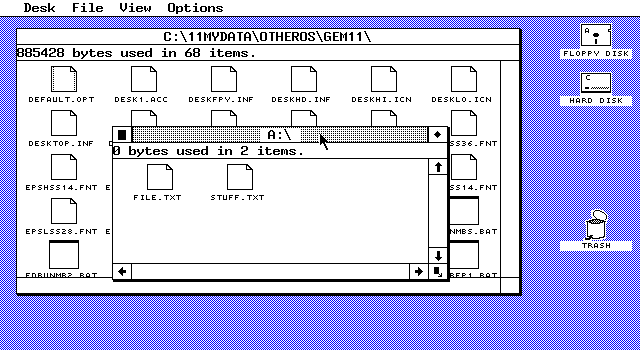

My first DnD encounter was by proxy. In about 1985 my then boss, a wise and cynical old Brummie engineer, attended a promotional demo, free wine and nibbles, of an exciting new WIMP technology called GEM. Part of the demo was to demonstrate the use of the on-screen trash icon for deleting files.

According to Graham’s gleeful report, he stuck up his hand at this point. “What happens if you drag the clock into the wastepaper basket?’

The answer turned out to be: the machine crashed hard on its arse, and it needed about 10 minutes embarrassed fiddling to coax it back onto its feet. At which point Graham’s arm went up again. “What happens if you drop the wastepaper basket into the clock?’

Drag-ons ‘n’ drag-offs

GEM may have been primitive, but it was at least consistent.

The point became moot a few months later, when Apple won a look-and-feel lawsuit and banned the GEM trashcan outright.

2018: Not that much has changed. Windows Explorer users: how often has your mouse finger proved insufficiently strong to grasp the file? And you have accidentally dropped the document you wanted into a deep thicket of nested server directories?

Or how about touch interface DnD on a phone, where your skimming pinkie exactly masks from view the dragged thing?

Well then.

However, I do confess admiration for this JavaScript library that aims to make a dragging and dropping accessible to the blind. Can’t fault its ambition.

September 23, 2018

The Nimrod MRA4 – the world’s most expensive bad aircraft

Back in 2011, I posted an article about the retirement of the Hawker Siddeley Nimrod from the Royal Air Force inventory. I referred to the Nimrod as

… expensive to buy, eye-wateringly expensive to upgrade, but it must be cheap to operate, right? No:

[…] our new fleet of refurbished De Havilland Comet subhunters (sorry, “Nimrod MRA4s”) will cost at least £700m a year to operate. If we put the whole Nimrod force on the scrapheap for which they are so long overdue right now, by the year 2019 we will have saved […] £7bn

The Register certainly got in the right ballpark with this helpful graphic:

Earlier this month, the Nimrod saga was detailed at Naval Gazing, if only as a way to show that someone can have worse procurement experiences than the United States military. Despite being a military development of a passenger jet famous for crashes, the initial marks of the Nimrod were able to meet the RAF’s needs. The problems began when a requirement was generated for a British AWACS aircraft and the Nimrod was deemed to be the best candidate for conversion (“best” probably meaning “only British competitor”):

Things began to go wrong in the mid-70s, when the British decided to introduce an AWACS aircraft to support their air defense efforts. They had several options. The E-2 Hawkeye and E-3 Sentry were both about to enter service, and were rapidly proving themselves to have excellent radar systems during trials. The British could have had either aircraft, or bought their radar systems to integrate into an aircraft of their own. Or they could have only bought a few subcomponents, like the antenna or the radar transmitter itself, and built the rest domestically.

They decided to take none of these options. Instead, they would produce an entirely new radar system. Instead of an American-style radome, separate antennas would be installed in the nose and tail, and the system would sweep through one, and then the other. This was far more expensive and much riskier than buying from the Americans, but it did produce a lot more jobs in the British defense industry, which was apparently the government’s prime concern. In 1977, a contract was placed, making BAE and GEC-Marconi co-leads on the project to convert 11 surplus Nimrod MR1 airframes to the new configuration.

As might be expected based on that kind of decision-making, the resulting airplane had problems. The computer system chosen wasn’t powerful enough to integrate all of the data, particularly the area where the nose and tail radars overlapped. It was also horribly unreliable, with a mean time between failures of only two hours, in a system which took 2.5 hours to load the mission data from the tape. The Nimrod, considerably smaller than the American Sentry, was unable to carry more equipment to solve this problem. Different electronics racks were earthed to different points in the airframe, and the resulting potential differences caused false tracks to appear, overloading the computer even more. To make matters worse, most of the electronics units weren’t interchangeable for reasons that were never entirely clear. If one unit failed, several spares had to be tried before one that worked was found. The only system that functioned reliably was the IFF system, which could only track friendly aircraft and airliners. This was a major handicap in an aircraft intended to detect incoming Soviet bombers.

It probably isn’t a surprise to hear that the planes were delayed. A lot. And delaying military projects tends to drive the overall price higher. What was anticipated to be a £200-300 million project was over £1 billion before the government of the day came to their fiscal senses and pulled the plug (they ended up buying Boeing E-3 Sentry aircraft instead).

A few years later, the RAF ran a competition to replace the Nimrod MR2 maritime patrol aircraft. Lockheed, Dassault and Airbus entered the competition, but somehow, the RAF ended up selecting BAE’s bid which involved rebuilding 30-year-old Nimrod frames with new electronics and all the modern conveniences.

RAF Nimrod MRA4 on 18 July 2009.

Detail of original photo by Ronnie Macdonald, via Wikimedia Commons.

In 1996, a contract was issued for the new aircraft, designated Nimrod MRA4. 21 aircraft were to be produced at a cost of £2.8 billion, and they would be essentially new airplanes, with only the fuselage structure being retained. The antique Spey engines would be replaced with modern BR700s. These engines were significantly larger, and required much more air, forcing BAE to design a new, larger wing. The combined effect of these two changes was to double the Nimrod’s range and improve performance. Inside, the flight deck was replaced with one derived from the A340 airliner, and the mission systems were to be all-new.

A fuselage was sent to be reverse-engineered for the design of the new wing, and BAE designed and built it, then pulled in another aircraft to make the modification. And discovered that the wing didn’t fit. Apparently, the problem dated back to the initial construction of the aircraft. When positioning the frames, Hawker Siddeley had not done what all sensible manufacturers did, and measured from a common baseline. Instead, they had positioned each frame with a tolerance relative to the previous one, which meant that the position of the wings varied by as much as a foot across the fleet. Worse, the aircraft they had designed the wings for was one of the most extreme in wing position, so the new wings didn’t fit most of the other aircraft. This forced a redesign of the wings, further delaying the program.

Spoiler: they missed their delivery deadline. By nearly a decade. And the original plan to build 21 aircraft shrank to only 4 … but the budget continued to grow, from the original £2.8 billion to over £4.1 billion at cancellation. Each of the surviving airframes had literally cost more than £1 billion. That’s why Bean gave the Nimrod his “Naval Gazing Worst Procurement Ever” trophy, and I think it was very well-deserved.

September 22, 2018

The Distant Early Warning Line

The History Guy: History Deserves to Be Remembered

Published on 23 Apr 2018The History Guy examines how the Cold War transformed Canada with the establishment of the U.S. Air Force’s distant early warning or dew line.

The History Guy uses images that are in the Public Domain. As photographs of actual events are often not available, I will sometimes use photographs of similar events or objects for illustration.

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/TheHistoryGuy

The History Guy: Five Minutes of History is the place to find short snippets of forgotten history from five to fifteen minutes long. If you like history too, this is the channel for you.

September 19, 2018

QotD: The “generations” of jet fighters

American warplanes like the F-22 and F-35 are often called “5th generation” fighters. This leaves many wondering what the other generations were and what the next one will be. The generation reference is all because of jet fighters, and the first generation was developed during and right after World War II (German Me-262, British Meteor, U.S. F-80, and Russian MiG-15). These aircraft were, even by the standards of the time, difficult to fly and unreliable (especially the engines). The 2nd generation (1950s) included more reliable but still dangerous to operate aircraft like the F-104 and MiG-21. The 3rd generation (1960s) included F-4 and MiG-23. The 4th generation (1970s) included F-16 and MiG-29. Each generation has been about twice as expensive (on average, in constant dollars) as the previous one. But each generation is also about twice as safe to fly and cheaper to operate. Naturally, each generation is more than twice as effective as the previous one. Increasingly it looks like the 6th generation will come without pilots. That’s because producing fifth generation fighters has proved difficult as well as very expensive. So far only the United States has managed to get 5th gen fighters (F-22 and F-35) into service. The Russians are still trying as are the Chinese, even though one of their stealth fighter designs (J-20) is technically in service (even though production has been suspended after less than a dozen were produced).

The Russians have said they will keep working on their 5th generation Su-57, although some of the derivatives of their Su-27 are at least generation 4.5. One of the reasons the Soviet Union collapsed was the realization that they could not afford to develop 5th generation warplanes to stay competitive with America. The Russians had a lot of interesting stuff on the drawing board and in development but the bankruptcy of most of their military aviation industry during the 1990s left them scrambling to put it back together ever since. At the moment the Russians are thinking of making a run for the 6th generation warplanes, which will likely be unmanned and largely robotic. As of 2018 they don’t have much choice because their answer to the F-22, work on the Su-57 was canceled (“indefinitely paused”.)

“Murphy’s Law: The Impossible 5th Generation”, Strategy Page, 2018-08-20.

September 13, 2018

Mind Your Business Ep. 2: Aceable in the Hole

Foundation for Economic Education

Published on 11 Sep 2018Believe it or not, parallel parking is not an impossible task. Meet Blake Garrett, the entrepreneur who is using VR to teach people how to drive, without actually getting behind the wheel.

____________

Produced & Directed by Michael Angelo Zervos

Executive Produced by Sean W. Malone

Hosted by Andrew Heaton

Original Music by Ben B. Goss

Featuring Blake Garrett

September 12, 2018

How Do Light Bulbs Work? | Earth Lab

BBC Earth Lab

Published on 1 Nov 2013James May explains one of the most important inventions to modern life: the lightbulb.

“Subscribe to Earth Lab for more fascinating science videos – http://bit.ly/SubscribeToEarthLab

All the best Earth Lab videos http://bit.ly/EarthLabOriginals

Best of BBC Earth videos http://bit.ly/TheBestOfBBCEarthVideosHere at BBC Earth Lab we answer all your curious questions about science in the world around you. If there’s a question you have that we haven’t yet answered or an experiment you’d like us to try let us know in the comments on any of our videos and it could be answered by one of our Earth Lab experts.

September 11, 2018

Fear the Internet-of-Things

Martin Giles talks to Bruce Schneier about his new book, Click Here to Kill Everybody:

The title of your book seems deliberately alarmist. Is that just an attempt to juice sales?

It may sound like publishing clickbait, but I’m trying to make the point that the internet now affects the world in a direct physical manner, and that changes everything. It’s no longer about risks to data, but about risks to life and property. And the title really points out that there’s physical danger here, and that things are different than they were just five years ago.

How’s this shift changing our notion of cybersecurity?Our cars, our medical devices, our household appliances are all now computers with things attached to them. Your refrigerator is a computer that keeps things cold, and a microwave oven is a computer that makes things hot. And your car is a computer with four wheels and an engine. Computers are no longer just a screen we turn on and look at, and that’s the big change. What was computer security, its own separate realm, is now everything security.

You’ve come up with a new term, “Internet+,” to encapsulate this shift. But we already have the phrase “internet of things” to describe it, don’t we?

I hated having to create another buzzword, because there are already too many of them. But the internet of things is too narrow. It refers to the connected appliances, thermostats, and other gadgets. That’s just a part of what we’re talking about here. It’s really the internet of things plus the computers plus the services plus the large databases being built plus the internet companies plus us. I just shortened all this to “Internet+.”

Let’s focus on the “us” part of that equation. You say in the book that we’re becoming “virtual cyborgs.” What do you mean by that?

We’re already intimately tied to devices like our phones, which we look at many times a day, and search engines, which are kind of like our online brains. Our power system, our transportation network, our communications systems, are all on the internet. If it goes down, to a very real extent society grinds to a halt, because we’re so dependent on it at every level. Computers aren’t yet widely embedded in our bodies, but they’re deeply embedded in our lives.

Can’t we just unplug ourselves somewhat to limit the risks?

That’s getting harder and harder to do. I tried to buy a car that wasn’t connected to the internet, and I failed. It’s not that there were no cars available like this, but the ones in the range I wanted all came with an internet connection. Even if it could be turned off, there was no guarantee hackers couldn’t turn it back on remotely.

Hackers can also exploit security vulnerabilities in one kind of device to attack others, right?

There are lots of examples of this. The Mirai botnet exploited vulnerabilities in home devices like DVRs and webcams. These things were taken over by hackers and used to launch an attack on a domain-name server, which then knocked a bunch of popular websites offline. The hackers who attacked Target got into the retailer’s payment network through a vulnerability in the IT systems of a contractor working on some of its stores.