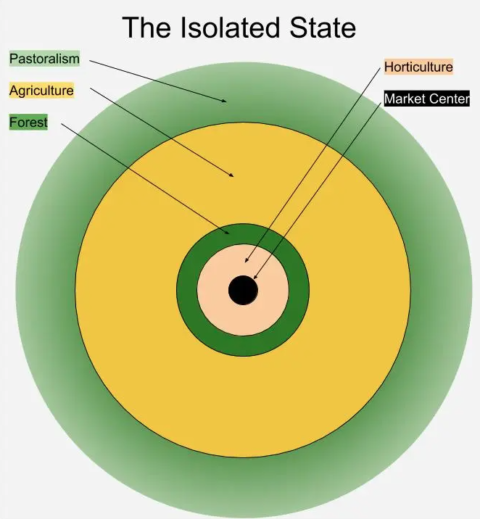

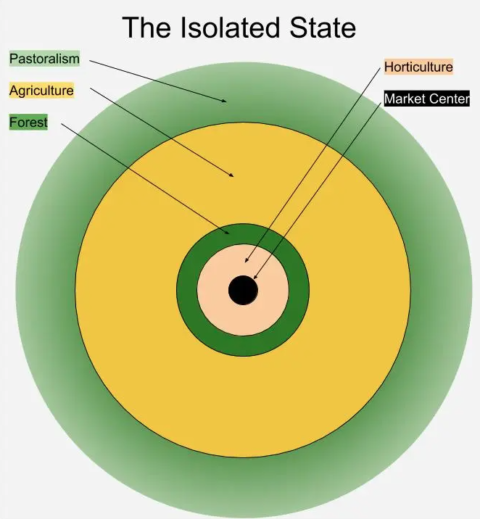

Diagram of von Thünen’s model from The Isolated State, after Morley (1996), 62. The agriculture ring is subdivided by intensity (intensive, long-lay and three-field), but here I have merged them for simplicity. The agriculture zone is wider because it did, in fact, tend to cover a larger area. The fade in the pastoralism zone is meant to indicate shifts from ranching to transhumance.

We’ll start at the inside, right next to the city and move outward. Imagine each “zone” as a wider concentric circle, moving outward from the city (see the image to the right). Because transportation costs (especially overland) are so high, distance from the city plays a dominant role in how the land is used and thus consequently what the countryside around the city looks like. As you move further and further away, transportation costs interact with the structure of agriculture to make different activities make more sense, creating somewhat predictable patterns.

Land very close to the city is valuable because its produce can reach the market with much lower transportation costs (and pretty much always in a single day’s walk). As a result, if the land can support any kind of productive use, it will not be left empty. Instead, the land is going to be put to the most productive use possible. Improvements that – because of cost or labor – might not be attempted on less valuable land further out will likely be done in close proximity to the city. Stepping out of our ideal model for a moment: this is especially true of irrigation, since cities tend to be on waterways (especially rivers) anyway, making irrigation both more valuable due to low transport costs and easier to accomplish.

Thus land in this innermost zone is likely to be heavily improved (irrigation, terracing to get maximum space out of hills, etc). Labor use will also be intensive, both because it is readily available (you are right next to the major population center) and because labor costs are small compared to the high value of the land. If you have managed to get some farmland right outside the city gates, it is very much worth your time to hire whatever labor you need to get the most out of it, so as to recoup the cost of buying or holding such valuable land.

The other improvement one is likely to do in this zone, at least for growing crops, is make extensive use of fertilizer, which in this case generally means manure. The good news is that this zone is directly next to the city, with its intense concentration of animals and people producing manure, making manure cheaper (yes, people did pay for it). Extensive use of manure lets the fields stay under cultivation more often – being fallowed less frequently. At greater distance, the cost of the manure for this begins to outweigh the value of the extra crops, but so close to the city, land this valuable ought to be kept producing as much as possible.

So what kinds of land use does this lead to? The two key activities that von Thünen identifies are horticulture and dairying, to which I’ll add trough-fed animals like pigs (not quite dairy, but as we’ll see, similar from an economic perspective). Why? Horticulture – the intensive growing of fruits and vegetables, often in small “market gardens” – is labor intensive and offers a high economic yield for the space. Land used for horticulture can be kept under almost continual cultivation (if manured, but see above), but gardens can be fussy and demand quite a lot of labor, compared to hardier plants (like maize corn or wheat). Likewise, dairy animals (which, up close to a large city, will be stall-fed rather than grazed or else transported in “on the hoof” and grazed much further out) and pigs (fed by trough) don’t require much space and offer a high economic yield. Both also produce manure which is in demand near the city for the reasons described above.

The other reason to keep these activities so close to the city is access to the market, for two related reasons. First, fresh dairy products, meats and vegetables spoil rapidly, so they must be gotten to market quickly. Remember that this is a world without refrigeration, so as soon as the plant is picked, the cow is milked or the pig is killed, the clock is ticking on spoilage (yes, there are ways to preserve meat, of course – but we’re talking fresh animal products). Precisely because these foods don’t travel or keep well, they tend to be luxury products as well – something produced for the market and bought by rich non-farmers who live in the city.

So what kind of terrain should we see here? Not open grassland or nice wide open fields. Instead, expect small plots, with clustered buildings, typically clinging to the roads leading into the city. Now – especially in the post-gunpowder age – there might be laws forbidding certain kinds of structures close to the city walls (if the city is walled), which might create some open space (but typically not vast). Likewise, when looking at historical city maps, also be wary: this innermost land-use zone was often contained within the city walls of smaller cities.

The next zone – also quite close to the city in von Thünen’s model is – perhaps somewhat surprisingly – a forest zone. That’s not to say that this is generally wild, uncontrolled forest. The reason for a forest zone at such close distance to the city is to provide wood, particularly firewood for heating. Trees might be arranged intentionally along field separations or on spots of agriculturally marginal land close to the city. Forests like these in the Middle Ages would often have been coppiced or pollarded – that is, the trees would have been intentionally cut to produce lots of long, thin straight branches which can be easily harvested to produce nice, evenly sized bits of wood.

Wood is obviously at no risk of spoiling, but it is heavy and bulky, making a close supply valuable. Moreover, the city will need quite a lot of it, for cooking and heating. That said, trees can often be grown either on very marginal (for agriculture) land or else between fields and farms outside of the city, so these patches of forest might often go on land that is a touch too rough or poor for intensive agriculture, or otherwise be squeezed in between land used for other purposes. Still, it is quite common to find spots of forest next to cities and villages alike.

(To answer a quibble in advance: of course this assumes wood is a key heating element. Societies in more arid climates often lack sufficient wood and might use dung, while wet enough areas may use peat. Historically, London shifted over to using mineral coal earlier than most places. All of these choices will impact the role and importance of forest near the city.)

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: The Lonely City, Part I: The Ideal City”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2019-07-12.