We’re getting closer to the end of the series now … you can catch up to the earlier posts here: part one, part two, part three, part four, part five, part six, and part seven. The previous post touched on Russia’s disaster in the far east and the dangerous domestic situation it faced after the war. In this post we discover that Italy could be at least as perfidious as “Perfidious Albion”, and that the Balkans are a hell of a place to wage a war.

Italy tips the first domino … in Africa

In The Sleepwalkers, Christopher Clark talks about a war I don’t think I’d ever heard of … an Italian campaign against the Ottoman Empire:

At the end of September 1911, only six months after the foundation of Ujedinjenje ili smrt! [“Union or death!” aka The Black Hand], Italy launched an invasion of Libya. This unprovoked attack one one of the integral provinces of the Ottoman Empire triggered a cascade of opportunistic attacks on Ottoman-controlled territory in the Balkans.

Italy’s attack on the Ottoman Empire was literally planned to steal what is now Libya and incorporate it into a new Italian Empire. Although the formal war was over in thirteen months, indigenous Arabs were still fighting back twenty years later. This attack broke the public-but-informal international understandings about leaving the remaining parts of the Ottoman Empire alone to prevent the risk of great power struggles breaking out. Britain and France had gone to war in 1854 to ensure that Russia did not gain access to the straits and thus a warm-water route to the Mediterranean and the coastlines of southern Europe, but the outcome of both the 1870-71 Franco-Prussian War and the 1877-78 Russo-Turkish War (and the secret Reinsurance Treaty with Germany) meant that Russia’s hands were largely free as long as Constantinople and the straits were not directly attacked. Italy’s attack broke with that understanding, and could be said to have started the most recent (and also most fatal) scramble for territory in the Balkans.

However, Italy did not act completely outside the norm for a would-be great power: they had an understanding with the French government that was formalized in a secret treaty in 1902 — Italy would not oppose French designs on Tunisia in exchange for French acceptance of Italy’s similar hopes for Tripolitania and Cyrenaica (modern day Libya). Italy’s attack was only possible because of the anomaly of the British position in Egypt: although still formally part of the Ottoman Empire, day-to-day Egyptian affairs were run by or overseen by British officials. Egypt was militarily occupied, but not a colony of the British Empire, and the country was — in theory — still run by the government of the Khedive. The Ottomans could not move formed bodies of troops through Egypt, and the Ottoman navy did not have the ships to transport them from Anatolia directly to Libya. This gave Italy the opportunity to concentrate against the weaker Ottoman forces.

The otherwise obscure Italo-Turkish War was interesting for several reasons, as the Wikipedia article notes:

Although minor, the war was a significant precursor of the First World War as it sparked nationalism in the Balkan states. Seeing how easily the Italians had defeated the weakened Ottomans, the members of the Balkan League attacked the Ottoman Empire before the war with Italy had ended.The Italo-Turkish War saw numerous technological changes, notably the airplane. On October 23, 1911, an Italian pilot, Captain Carlo Piazza, flew over Turkish lines on the world’s first aerial reconnaissance mission, and on November 1, the first ever aerial bomb was dropped by Sottotenente Giulio Gavotti, on Turkish troops in Libya, from an early model of Etrich Taube aircraft. The Turks, lacking anti-aircraft weapons, were the first to shoot down an aeroplane by rifle fire.

It was also in this conflict that the future first president of Turkey and leader of the Turkish War of Independence, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, distinguished himself militarily as a young officer during the Battle of Tobruk.

Although Italy ended up with possession of the disputed land, it did not come easily or cheaply:

The invasion of Libya was a costly enterprise for Italy. Instead of the 30 million lire a month judged sufficient at its beginning, it reached a cost of 80 million a month for a much longer period than was originally estimated. The war cost Italy 1.3 billion lire, nearly a billion more than Giovanni Giolitti estimated before the war. This ruined ten years of fiscal prudence.

After the withdrawal of the Ottoman army the Italians could easily extend their occupation of the country, seizing East Tripolitania, Ghadames, the Djebel and Fezzan with Murzuk during 1913. The outbreak of the First World War with the necessity to bring back the troops to Italy, the proclamation of the Jihad by the Ottomans and the uprising of the Libyans in Tripolitania forced the Italians to abandon all occupied territory and to entrench themselves in Tripoli, Derna, and on the coast of Cyrenaica. The Italian control over much of the interior of Libya remained ineffective until the late 1920s, when forces under the Generals Pietro Badoglio and Rodolfo Graziani waged bloody pacification campaigns. Resistance petered out only after the execution of the rebel leader Omar Mukhtar on September 15, 1931. The result of the Italian colonisation for the Libyan population was that by the mid-1930s it had been cut in half due to emigration, famine, and war casualties. The Libyan population in 1950 was at the same level as in 1911, approximately 1.5 million in 1911.

The war ended well — at least geographically speaking — for Italy, having gained title not only to Libya but also to the Dodecanese: a group of twelve large and about 150 small islands in the Aegean Sea. The largest and most economically valuable island was Rhodes, which became a useful base for Italian forces for more than 40 years. The treaty ending the Italo-Turkish War required Italy to vacate the islands, but due to both fuzzy wording and the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire at the end of the First World War, Italy managed to retain possession.

The Ottoman tide ebbs

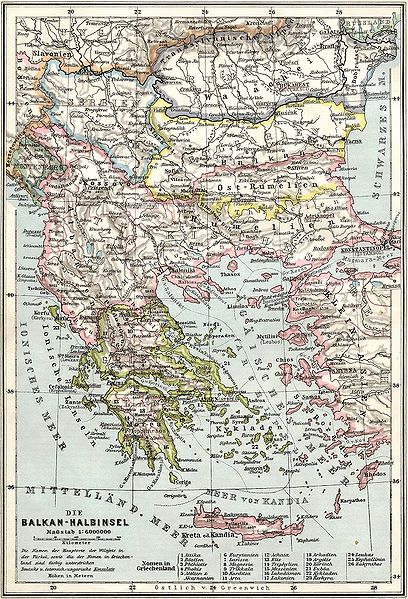

The remaining Ottoman territories in Europe were under constant pressure both from external forces (Austria and Russia) and internal linguistic, religious, and cultural separatist movements. Austria preferred to view the separatists as potential new provinces for the Dual Monarchy, while Russia saw the possibility of new independent Russophile political groupings that might allow indirect Russian access to the Mediterranean, bypassing Constantinople (or, perhaps more realistically, additional bases from which to launch an attack against the straits).Italy’s attack was the first domino falling. Christopher Clark writes:

The First World War was the Third Balkan War before it became the First World War. How as this possible? Conflicts and crises on the south-eastern periphery, where the Ottoman Empire abutted Christian Europe, were nothing new. The European system had always accommodated them without endangering the peace of the continent as a whole. But the last years before 1914 saw fundamental change. In the autumn of 1911, Italy launched a war of conquest on an African province of the Ottoman Empire, triggering a chain of opportunistic assaults on Ottoman territories across the Balkans. The system of geopolitical balances that had enabled local conflicts to be contained was swept away. In the aftermath of the two Balkan Wars of 1912 and 1913, Austria-Hungary faced a new and threatening situation on its south-eastern periphery, while the retreat of Ottoman power raised strategic questions that Russian diplomats and policy-makers found it impossible to ignore.

Margaret MacMillan, in The War That Ended Peace:

It was in the Balkans […] that the greatest dangers were to arise: two wars among its nations, one in 1912 and a second in 1913, nearly pulled the great powers in. Diplomacy, bluff and brinksmanship in the end saved the peace but although Europeans could not know it, they had had a dress rehearsal for the summer of 1914. As they say in the theatre, if that last run-through goes well, the opening night will be a disaster.

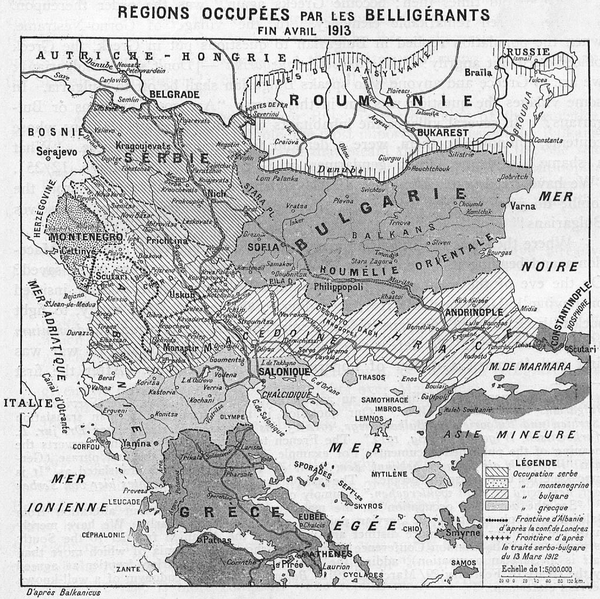

The First Balkan War of 1912 — A Pan-Slavic triumph

To some, the Balkans were a comic opera assemblage of exotic uniforms, passionate actors, indecipherable languages, a bit of bloodshed, but no real source of international danger or worry. Margaret MacMillan explains that much happened beneath the surface of the above-ground culture: much that portended danger to the entire region and beyond.

To the rest of Europe the Balkan states were something of a joke, the setting for tales of romance such as the Prisoner of Zenda or operettas (Montenegro was the inspiration for the The Merry Widow), but their politics were deadly serious — and frequently deadly with terrorist plots, violence and assassinations. In 1903 King Peter’s unpopular predecessor as King of Serbia and his equally unpopular wife had been thrown from the windows of the palace and their corpses hacked to pieces. […] The growth of national movements had welded peoples together but it had also divided Orthodox from Catholic or Muslim, Albanians from Slaves, and Croats, Serbs, Slovenes, Bulgarians or Macedonians from each other. While the peoples of the Balkans had coexisted and intermingled, often for long periods of peace through the centuries, the establishment of national states in the nineteenth century had too often been accompanied by burning of villages, massacres, expulsions of minorities and lasting vendettas.

Politicians who had ridden to power by playing on nationalism and with promises of national glory found they were in the grip of forces they could not always control. Secret societies, modelling themselves on an eclectic mix which included Freemasonry, the underground Carbonari, who had worked for Italian unity, the terrorists who more recently had frightened much of Europe, and old-style banditry, proliferated throughout the Balkans, weaving their way into civilian and military institutions of the states.

In addition to the ethnic, proto-national, cultural, and religious aspects of Balkan conflict, it was also an inter-generational conflict:

Comic opera states or not, they proved to be more than a match for their Ottoman overlords. Taking advantage of the Italian attack on Libya, Serbia allied with Bulgaria, Greece, and Montenegro to invade and capture much of the Balkan peninsula, stopping just a few miles outside Constantinople. The First Balkan War triggered vast population shifts, as nearly half a million Muslims fled from the conquered territory to escape religious persecution (and many thousands died through privation, disease, and starvation. Between the actual combat between military forces, forced evacuations, and the early use of genocidal policies, several million people were forced out of their homes and moved at gunpoint to wherever the armed groups wanted them to go. Cultural patterns nearly a millennia old were uprooted and dispersed to suit the tastes of local warlords and jumped-up military leaders.The younger generation who were attracted to the secret societies were often more extreme than their elders and frequently at odds with them. “Our fathers, our tyrants,” said a Bosnian radical nationalist, “have created this world on their model and are now forcing us to live in it.” The young members were in love with violence and prepared to destroy even their own traditional values and institutions in order to build the new Greater Serbia, Bulgaria, or Greece. (Even if they had not read Nietzsche, which many of them had, they too had heard that God was dead and that European civilization must be destroyed in order to free humankind.) In the last years before 1914, the authorities in the Balkan states either tolerated or were powerless to control the activities of their own young radicals who carried out assassinations and terrorist attacks on Ottoman or Austrian-Hungarian official as oppressors of the Slavs, on their own leaders whom they judged to be insufficiently devoted to the nationalist cause, or simply on ordinary citizens who happened to be in the wrong religion or the wrong ethnicity in the wrong place.

And there it might have ended, but the unexpectedly successful campaign by the Balkan League left just a few too many loose ends, which almost immediately led to conflict among the victorious allies. Since I’ve already tipped you to the fact that there was more than one Balkan War, you probably won’t be surprised to find that the Second Balkan War happened quite soon after the first one. But that’s a tale for another day.