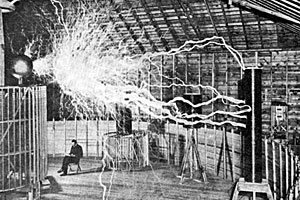

What went wrong in the 1970s? Since then, growth and productivity have slowed, average wages are stagnant, visible progress in the world of “atoms” has practically stopped — the Great Stagnation. About the only thing that has gone well are computers. How is it that we went from the typewriter to the smartphone, but we’re still using practically the same cars and airplanes?

Where is my Flying Car? by J. Storrs Hall, is an attempt to answer that question. His answer is: the Great Stagnation was caused by energy usage flatlining, which was caused by our failure to switch to nuclear energy, which was caused by excessive regulation, which was caused by “green fundamentalism”.

Three hundred years ago, we burned wood for energy. Then there was coal and the steam engine, which gave us the Industrial Revolution. Then there was oil and gas, giving us cars and airplanes. Then there should have been nuclear fission and nanotech, letting you fit a lifetime’s worth of energy in your pocket. Instead, we still drive much the same cars and airplanes, and climate change threatens to boil the Earth.

I initially thought the title was a metaphor — the “flying car” as a standin for all the missing technological progress in the world of “atoms” — but in fact much of the book is devoted to the particular question of flying cars. So look at the issue from the lens of transportation:

Hans Rosling was a world health economist and an indefatigable campaigner for a deeper understanding of the world’s state of development. He is famous for his TED talks and the Gapminder web site. He classifies the wealthiness of the world’s population into four levels:

1. Barefoot. Unable even to afford shoes, they must walk everywhere they go. Income $1 per day. One billion people are at Level 1.

2. Bicycle (and shoes). The $4 per day they make doesn’t sound like much to you and me but it is a huge step up from Level 1. There are three billion people at level 2.

3. The two billion people at Level 3 make $16 a day; a motorbike is within their reach.

4. At $64 per day, the one billion people at Level 4 own a car.

The miracle of the Industrial Revolution is now easily stated: In 1800, 85% of the world’s population was at Level 1. Today, only 9% is. Over the past half century, the bulk of humanity moved up out of Level 1 to erase the rich-poor gap and make the world wealth distribution roughly bell-shaped. The average American moved from Level 2 in 1800, to level 3 in 1900, to Level 4 in 2000. We can state the Great Stagnation story nearly as simply: There is no level 5.

Level 5, in transportation, is a flying car. Flying cars are to airplanes as cars are to trains. Airplanes are fast, but getting to the airport, waiting for your flight, and getting to your final destination is a big hassle. Imagine if you had to bike to a train station to get anywhere (not such a leap of imagination for me in New York City! But it wouldn’t work in the suburbs). What if you had one vehicle that could drive on the road and fly in the sky at hundreds of miles an hour?

Before reading this book, I thought flying cars were just technologically infeasible, because flying takes too much energy. But Hall says we can and have built them ever since the 1930s. They got interrupted by the Great Depression (people were too poor to buy private airplanes), then WWII (airplanes were directed towards the war effort, not the market), then regulation mostly killed the private aviation industry. But technical feasibility was never the problem.

Hall spends a huge fraction of the book on pretty detailed technical discussion of flying cars. For example: the key technical issue is takeoff and landing, and there is a tough tradeoff between convenient takeoff/landing and airspeed (and cost, and ease of operation). It’s interesting reading. But let’s return to the larger issue of nuclear power.

General Motors has emerged from bankruptcy and taken initial steps to repay its federal bailout money — two good bits of news, although the taxpayer remains on the hook for many billions of dollars extended to GM. Specialty electric-car maker Tesla Motors also had a successful initial public offering and is being celebrated as some kind of testament to the entrepreneurial spirit. For Tesla, this is pure PR.

General Motors has emerged from bankruptcy and taken initial steps to repay its federal bailout money — two good bits of news, although the taxpayer remains on the hook for many billions of dollars extended to GM. Specialty electric-car maker Tesla Motors also had a successful initial public offering and is being celebrated as some kind of testament to the entrepreneurial spirit. For Tesla, this is pure PR. The other absurd vehicle in development is the Terrafugia flying car, which just won exemption from a federal airworthiness safety standard. Surely you will feel secure when a flying car exempted from safety standards buzzes your neighborhood, especially when you learn that another federal waiver means the pilot needs only 20 hours of experience before he or she takes off. Maryland, my state, requires 60 hours behind the wheel before receiving a driver’s license. But fly after 20 hours? Hey, wheels up! Surely few of these accidents-looking-for-a-place-to-happen will sell on the free market. So — scan the horizon for a bailout. The Terrafugia company just got a piece of a $65 million military contract to research a flying Jeep-like thing; don’t hold your breath. If patriotism is the last refuge of scoundrels, defense contracting is the last refuge of bad business plans.

The other absurd vehicle in development is the Terrafugia flying car, which just won exemption from a federal airworthiness safety standard. Surely you will feel secure when a flying car exempted from safety standards buzzes your neighborhood, especially when you learn that another federal waiver means the pilot needs only 20 hours of experience before he or she takes off. Maryland, my state, requires 60 hours behind the wheel before receiving a driver’s license. But fly after 20 hours? Hey, wheels up! Surely few of these accidents-looking-for-a-place-to-happen will sell on the free market. So — scan the horizon for a bailout. The Terrafugia company just got a piece of a $65 million military contract to research a flying Jeep-like thing; don’t hold your breath. If patriotism is the last refuge of scoundrels, defense contracting is the last refuge of bad business plans.