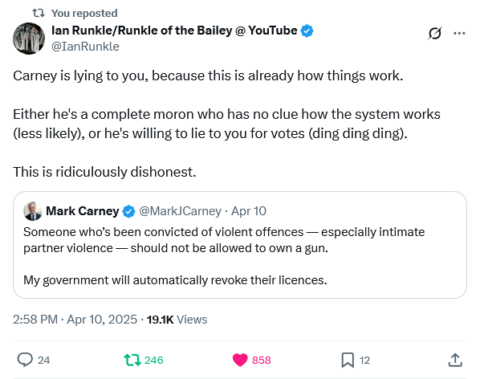

Among the Conservative and Liberal mis-steps of the election campaign this week, the promise by Liberal leader Mark Carney to pass legislation to boldly and courageously do something that has been part of the firearms laws for over 40 years deserves calling out:

Your Line editors knew that guns were going to come into the campaign eventually. It’s one of the eternal issues for the Red Team, and while they seemed to have shied away from it a bit after some pretty brutal fumbling in Justin Trudeau’s later years, we figured it would be back eventually. And so it was on Thursday, when Liberal leader Mark Carney announced, as part of a package of crime policy proposals, that a re-elected Liberal government would make sure that guns were automatically taken from anyone convicted of a violent crime, including intimate partner violence.

*pulls hard on chain, activating bullshit klaxon*

See, here’s the thing, friends. First of all, to take Carney at his word here would require us accepting, even just for a moment, that this didn’t already happen. That up until Thursday of this week, the Liberals were hunky dory with people convicted of violent crimes, including intimate partner violence, keeping whatever guns they may own or wish to acquire.

That is, we suspect readers know, utter bullshit. Removing guns is already required in those circumstances, and it doesn’t even require a conviction. Police officers can seize any weapon of any type if it isn’t in the safety interest of any person, even without a warrant, and revoke any license they hold immediately.

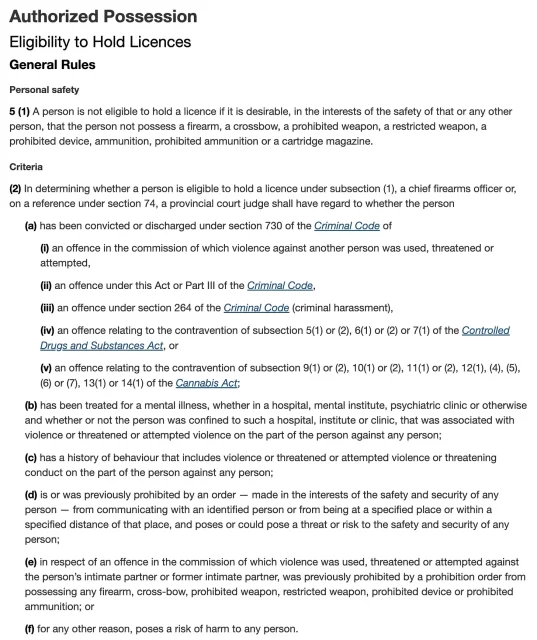

Nobody is eligible to hold a license if it isn’t in the safety interest of a person — that’s literally the first eligibility criterion in the Firearms Act. Issuing a license requires the issuer to consider all past convictions, mental illnesses, history of violent behaviour, previous prohibitions, any potential intimate partner violence, and any potential harm to any person before they issue it. That is checked through a process called Continuous Eligibility Screening, where license holders are checked for “hits” against police systems every single day to determine whether they are still able to hold a license.

This is something almost no one outside Canada’s firearms-owning community understands, and The Line wants to underline this point — anyone with a firearms licence is automatically checked for any new legal issues that might render them unable to own firearms every single day. If you happen to find yourself hanging out with someone with a firearms licence, they were checked out by law enforcement within the last 24 hours. This includes your friends at The Line. The day you’re reading this is a day they passed another screening.

A conviction for a violent crime, it hardly need be said — well, actually, check that, apparently it does need saying — would render one rather ineligible! Not only is this already the law, but there are so many overlapping laws to deal with that exact scenario that it takes real effort to be ignorant of them. Weapon prohibition orders on conviction for violent offences? Already a thing at the federal and provincial levels. Prohibitions while on bail? Already a thing. Firearm seizures during divorces? Not automatic, but common, sometimes even where there is no history of violence or reasonable belief that violence is likely.

The Liberals know all this, especially since it was the Liberals who last changed these laws — though not to add the removal provisions, which largely already existed, but to remove any discretion or ability for rehabilitation.

Every party is fine with keeping guns away from domestic violence perpetrators. Carney making this an issue is bullshit. He’s counting on the public to not know enough to call him out on it.

It’ll probably work.

Oh, and by the way. If you don’t want to take our word for any of the above, you can just read the Firearms Act yourself. Relevant section, below.