David Friedman is a very intelligent man and I wouldn’t want to face him in a debate, even on a topic I feel well-informed about. He’s not a scientist and hasn’t made a serious study of climate but he can read the reports and make up his own mind. He’s inclined to believe the data available indicates that the planet is warming but he isn’t convinced that this is enough to justify the kind of authoritarian controls that climate activists demand:

The argument for doing drastic things to prevent global warming has two parts. The first has to do with reasons to think that the earth is getting warmer and that the reason is human action, in particular the production of CO2. The second is the claim that changes we have good reason to expect if we do not take appropriate action to prevent them will have very bad consequences for us.

Much of the criticism I have seen of the argument has to do with the first half, with critics arguing that the evidence for global warming, at least the evidence that it is caused by humans and will continue if humans do not mend their ways, is weak. I do not not know enough to be certain that those criticisms are wrong; climate is a very complicated and not terribly well understood subject.1 But my best guess from watching the debate is that the first half of the argument is correct, that global climate is warming and human action is an important part of the cause. What I find unconvincing is the second half of the argument, the claim that climate change we have good reason to expect would have catastrophic consequences for humans.

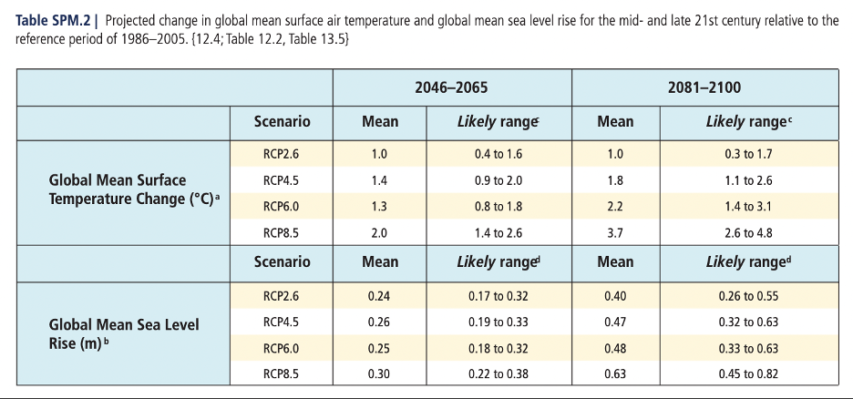

Obviously one can imagine climate change large enough and fast enough to be a very serious problem — a rapid end of the current interglacial, for example. If, as I believe is the case, climate is not very well understood, one cannot absolutely rule out such changes.2 But most of the argument is put in terms not of what might conceivably happen but of what we have good reason to expect to happen. I think the outer bound of that is provided by the IPCC models. They suggest a temperature increase of a few degrees centigrade over the next hundred years resulting in a sea level rise of less than a meter.3

Comparing a map of global temperature to a map of population density shows densely inhabited regions with average temperatures from about 10°C to about 30°C, with some of the most densely inhabited regions at the high end of the range. I could find no empty areas that are hotter than all populated areas, hence no areas that are depopulated only because of how hot they are. If people can currently live, work, grow crops over a temperature range of twenty degrees it is hard to imagine any reason why most of them couldn’t continue to do so about as easily if average temperature shifted up by two or three degrees, with a century to adjust to the change.

That raises the question with which I titled this post: Does climate change catastrophe pass the giggle test? Is the claim that climate change on that scale would have catastrophic consequences one that a reasonable person should take seriously?

[…]

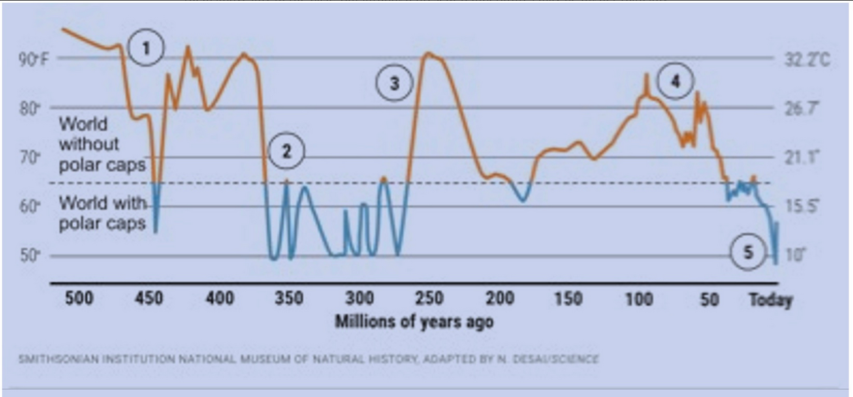

A different version of the catastrophist argument is the claim that climate is unstable, that an increase of a few degrees could trigger a much larger increase. That might be plausible if current temperatures were so high that additional warming would raise them above any in the past. But although present temperatures may be higher than any in the past two thousand years, as discussed in an earlier post, the Earth is much more than two thousand years old.

The graph below4 shows estimated global temperature over the past five hundred million years. While present temperature is high relative to the recent past it is cool relative to the more distant past, more than thirteen degrees below the high of the past hundred million years.

We are currently in an ice age, defined by geologists as a period when there is an ice cap on one or both poles. For most of the past five hundred million years there wasn’t.

The claim that we have good reason to expect climate change on a scale that will produce not merely problems for some but catastrophe for many is one that no reasonable person should take seriously.5

1. As some evidence, as of 2018 the temperature projections produced by the IPCC’s elaborate analysis did a somewhat worse job of predicting actual temperature than a straight line fit from the date when warming restarted after the midcentury pause to the date of each of the first four IPCC reports.

2. We cannot absolutely rule out catastrophic changes either caused by anthropogenic warming or prevented by anthropogenic warming. There is, in fact, some evidence, discussed in an earlier post, that the reason the next glaciation is not already starting is anthropogenic warming — not current warming due to the industrial revolution but warming that started some eight thousand years ago due to the invention of agriculture.

3. From Future Climate Changes, Risks and Impacts. RCP8.5 was originally designed as an upper bound on how high future CO2 emissions might be and assumed a level of world population growth that, so far, is not occurring, so should probably not be included.

4. The headline of the news story I found it in: “A 500-million-year survey of Earth’s climate reveals dire warning for humanity”.

If life gives you peaches, make cyanide from the pits.

5. The weaker claim that climate change will produce net costs for humans is, in my view, less obviously true than many believe. For reasons see my past posts on the subject.