Though the caste system dominates much of Indian life, it does not dominate Indian American life. At slightly over 1% of the U.S. population, only about half of Indian Americans identify as Hindu, the religion from which the broader categories of caste, or varna, emerge. While caste endogamy — marrying within one’s caste — in India remains in the range of 90%, in the U.S. only 65% of American-born Indians even marry other people of subcontinental heritage, and of these, a quick inspection of The New York Times weddings pages shows that inter-caste marriages are the norm. While tensions between the upper-caste minority and middle and lower castes dominate Indian social and political life, 85% of Indian Americans are upper-caste, broadly defined, and only about 1% are truly lower-caste. Ultimately, the minor moral panic over caste discrimination among a small minority of Americans is more a function of our nation’s current neuroses than the reality of caste in the United States.

But this does not mean that caste is not an important phenomenon to understand. In various ways, caste impacts the lives of the more than 1.4 billion citizens of India — 18% of humans alive today — whatever their religion. While the American system of racial slavery is four centuries old at most, India’s caste system was recorded by the Greek diplomat Megasthenes in 300 BC, and is likely far more ancient, perhaps as old as the Indus Valley Civilization more than 4,000 years ago. Indian caste has a deep pedigree as a social technology, and it illustrates the outer boundary of our species’ ability to organize itself into interconnected but discrete subcultures. And unlike many social institutions, caste is imprinted in the very genes of Indians today.

Of Memes and Genes

Beginning about twenty-five years ago, geneticists finally began to look at the variation within the Indian subcontinent, and were shocked by what they found. In small villages in India, Dalits, formerly called “outcastes,” were as genetically distinct from their Brahmin neighbors as Swedes were from Sicilians. In fact, a Brahmin from the far southern state of Tamil Nadu was genetically closer to a Brahmin from the northern state of Punjab then they were to their fellow non-Brahmin Tamils. Dalits from the north were similar to Dalits from the south, while the three upper castes, Brahmins, Kshatriyas and Vaishyas, tended to cluster together against the Sudras.

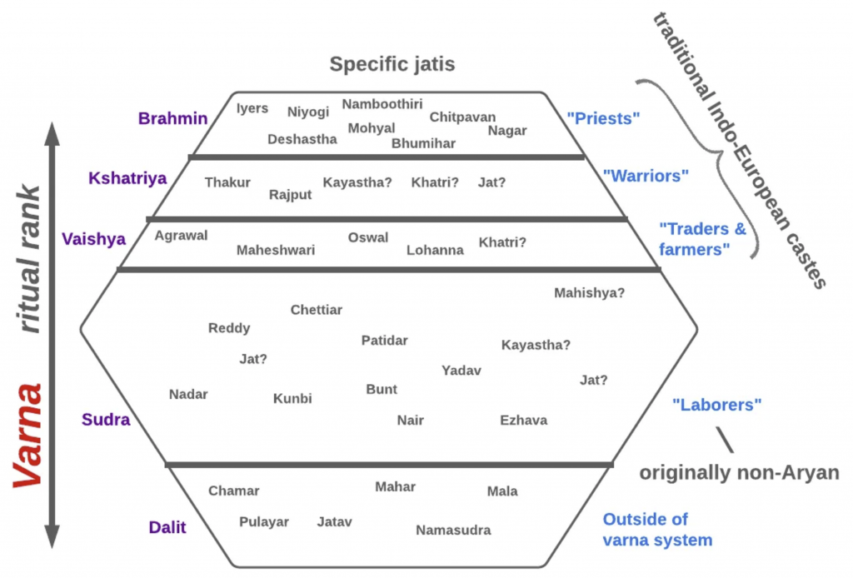

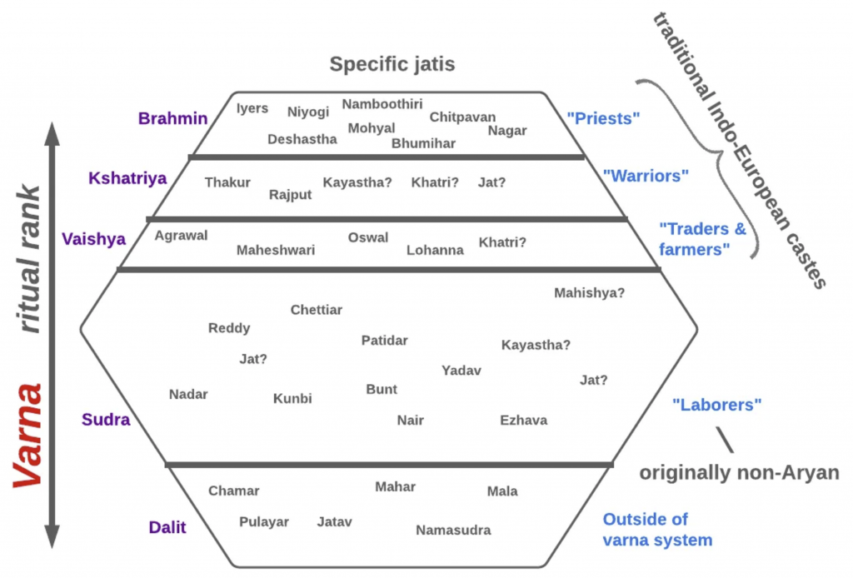

Some scholars, like Nicholas Dirks, the former chancellor of UC Berkeley, argued for the mobility and dynamism of the caste system in their scholarship. But the genetic evidence seemed to indicate a level of social stratification that echoes through millennia. Across the subcontinent, Dalit castes engaged in menial and unsanitary labor and therefore were considered ritually impure. Meanwhile, Brahmins were the custodians of the Hindu Vedic tradition that ultimately bound the Indic cultures together with other Indo-European traditions, like that of the ancient Iranians or Greeks. Other castes also had their occupations: Kshatriyas were the warriors, while Vaishyas were merchants and other economically productive occupations.

Brahmins, Kshatriyas, and Vaishyas were traditionally the three “twice-born” castes, allowing them to study the Hindu scriptures after an initiatory ritual. The majority of the population were Sudras (or Shudras), India’s peasant and laboring majority. Shudras could not study the scriptures, and might be excluded from some temples and festivals, but they were integrated into the Hindu fold, and served by Brahmin priests. A traditional ethnohistory posits that elite Brahmin priests and Kshatriya rulers combined with Vaishya commoners formed the core of the early Aryan society in the subcontinent, with Shudras integrated into their tribes as indigenous subalterns. Outcastes were tribes and other assorted latecomers who were assimilated at the very bottom of the social system, performing the most degrading and impure tasks.

The caste system as a layered varna system with five classes and numerous integrated jati communities.

Razib Khan

This was the theory. Reality is always more complex. In India, the caste system combines two different social categories: varna and jati. Varna derives from the tripartite Indo-European system, in India represented by Brahmins, Kshatriyas, and Vaishyas. It literally translates as “color”, white for Brahmin purity, red for Kshatriya power, and yellow for Vaishya fertility. But India also has Shudras, black for labor. In contrast to the simplicity of varna, with its four classes, jati is fractured into thousands of localized communities. If varna is connected to the deep history of Indo-Aryans and is freighted with religious significance, jati is the concrete expression of Indian communitarianism in local places and times.