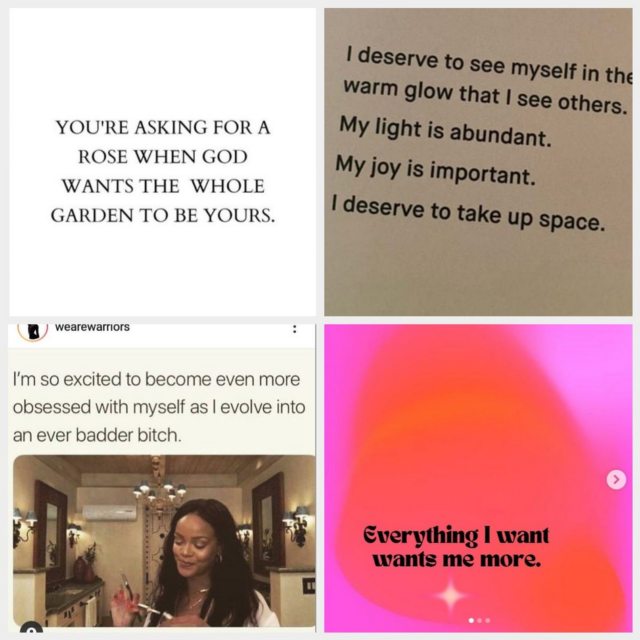

Freddie deBoer doesn’t have a catchy name for this, but you’ll recognize it instantly from the description:

For years now, I’ve written once or twice annually about a phenomenon that I’ve struggled to name but which everyone understands. It’s a particular kind of social and aesthetic culture, not exclusive to Instagram but very heavily associated with it, that merges girlboss feminism with the contemporary therapeutic imperative, a strange syncretic mysticism involving horoscopes and “manifesting”, and a blanket excuse for narcissism and selfishness dressed up in quasi-political and self-help terms. You know what I mean.

Some of these memes are comically ridiculous, most of them are fairly innocuous, and a few of them make me deeply sad. But they all reveal a tangle of conflicting attitudes and ideas that are quite confused. You would never assemble these various impulses into a life philosophy on purpose; they’ve been grafted together mostly thanks to the weird rhythms and path dependence of social media. Either way, I’ve argued that they present an essential problem with any kind of “I can have it all” philosophy — millions of people absorb this stuff, and because many of the things we want in life are zero sum, not all of them in fact can have it all. Almost all of them, in fact, will get very much less than it all. You have this absurd manifesting/The Secret stuff, where grown adults genuinely convince themselves that they can will what they want into being simply through wanting it. Well, alright: what if two people want the same promotion at work, and they’re both manifesting it? The clod philosophy this is all attached to says that whoever wins wanted it more, and since wanting can’t be quantified, no one can ever prove that isn’t true. (Convenient!) Regardless, in the case of the singular promotion and two people manifesting for it, only one of the people who has read endless memes like these actually ends up being self-actualized by success. This is OK; life can be full of contentment and disappointment at the same time. Part of what makes this kind of messaging pernicious, though, is that it suggests that not getting everything you want is always a personal failure you shouldn’t accept.

It is not possible that God promised the whole garden to everyone. (That’s not how fractions work, even for God.) It is not socially responsible to believe that you are entitled to the whole garden. And setting yourself up to see anything short of the whole garden as failure is a recipe for making yourself miserable.

That’s related to another point I’ve made, which is that these memes create an unachievable expectation that healthy, successful women aren’t in possession of ordinary confidence but of lunatic confidence, a kind of confidence rarely seen outside of Michael Jordan or bipolar mania. In a particularly perverse irony of the sort that seems to usually afflict women, this demand for outrageous self-confidence becomes just another bar that women feel like they can’t meet. A whole affirmational culture that ostensibly exists to help and affirm and praise women ends up being just one more on the long list of expectations that our society heaps on them: hard-charging and career-oriented but always putting family first, well put-together but always effortless, sexy but not slutty, Madonna and whore, you know the whole deal. I’m sorry that this stuff is so gendered, but it is, and I’m sorry that I’m the wrong messenger on this topic, but no one else is making these arguments, so I must. Yes, I concede that for most people who indulge in this stuff, it’s a harmless hobby that maybe pushes them to be a little better to themselves. But as time goes on, the messaging has grown more and more deranged, and young people are very susceptible to this sort of thing. And my job is to worry.