In UnHerd, Ashley Rindsberg recounts the details we know so far about the Guardian‘s embarassing historical project to find out about the newspaper’s links to the slave trade:

The Guardian prides itself on being one of the most Left-leaning and anti-racist news outlets in the English-speaking world. So imagine its embarrassment when, last month, a number of black podcast producers researching the paper’s historic ties to slavery abruptly resigned, alleging they had been victims of “institutional racism”, “editorial whiteness”, “microaggressions, colourism, bullying, passive-aggressive and obstructive management styles”. All of this might smack of progressive excess, but, in reality, it merely reflects an institution incuriously at odds with itself.

Questions about The Guardian‘s ties to slavery have been circulating since 2020, when, amid the media’s collective spasm of racial conscience following the murder of George Floyd, the Scott Trust announced it would launch an investigation into its history. “We in the UK need to begin a national debate on reparations for slavery, a crime which heralded the age of capitalism and provided the basis for racism that continues to endanger black life globally,” journalist Amandla Thomas-Johnson wrote in a June 2020 Guardian opinion piece about the toppling of a statue of 17th-century British slaver Edward Colston. A month later, the Scott Trust committed to determining whether the founder of the paper, John Edward Taylor, had profited from slavery. “We have seen no evidence that Taylor was a slave owner, nor involved in any direct way in the slave trade,” the chairman of the Scott Trust, Alex Graham, told Guardian staff by email at the time. “But were such evidence to exist, we would want to be open about it.” (Notably, Graham, in using the terms “slave owner” and “direct way”, set a very specific and very high bar for what would be considered information worthy of disclosure.)

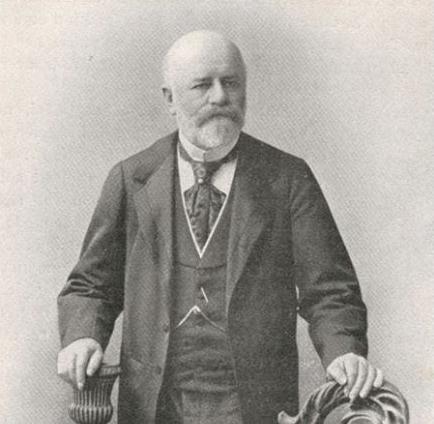

The problem is that the results of the investigation, conducted by historian Sheryllynne Haggerty, an “expert in the history of the transatlantic slave trade”, have never been made public. When contacted with questions about what happened to the promised report, Haggerty referred all inquiries to The Guardian‘s PR, which has remained silent on the matter. (The Guardian was asked for comment and we were given the stock PR response The Guardian gave following the podcaster’s letter.) But what we do know is this: according to Guardian lore, a business tycoon named John Edward Taylor was inspired to agitate for change after witnessing the 1819 Peterloo Massacre, when over a dozen people were killed in Manchester by government forces as they protested for parliamentary representation. Two years later, Taylor, a young cotton merchant, with the backing of a group of local reformers known as the Little Circle, founded the paper.

“Since 1821 the mission of The Guardian has been to use clarity and imagination to build hope,” The Guardian‘s current editor, Katharine Viner, proudly proclaims on the “About us” page of the paper’s website. Part of this founding myth concerns one of the defining social and political issues of the day, slavery, which the Little Circle members, including Taylor, vigorously opposed as a moral affront. “The Guardian had always hated slavery,” Martin Kettle, an associate editor, wrote in a 2011 apologia on why during the Civil War the paper had vociferously condemned the North while equivocating on the South.

That may be true, but it also presents an incomplete picture. The Manchester Guardian, as the paper was then known, was founded by cotton merchants, including Taylor, who were able to pool the money needed to launch the paper by drawing on their respective fortunes. While none of these men, many of whom were Unitarian Christians, is likely to have engaged in slavery, they didn’t just benefit from but depended upon the global slave trade that provided virtually all of the cotton that filled their mills. As Sarah Parker Remond, an African American abolitionist, said upon visiting Manchester in 1859: “When I walk through the streets of Manchester and meet load after load of cotton, I think of those 80,000 cotton plantations on which was grown the $125 million worth of cotton which supply your market, and I remember that not one cent of that money ever reached the hands of the labourers.”