Forgotten Weapons

Published 28 Sept 2015When the US entered WWII, submachine guns were in short supply and high demand. Much of the production of Thompson guns was being purchased by the UK, and what guns were available to the US military went first to the Army. In accordance with long tradition, the Marine Corps were secondary to the Army in receiving new weapons. However, the formation of a Marine paratroop unit in particular necessitated the Corps finding some sort of suitable submachine gun.

What was available at the time were Eugene Reising’s M50 and M55 guns, being manufactured by Harrington & Richardson. The guns were chambered for the standard .45ACP cartridge and used a delayed blowback action which allowed them to be significantly lighter than the Thompson. The M50 had a full-length traditional stock, while the M55 used a pistol grip and wire folding stock. Mechanically, the two variants were identical. The M55, which is what we have today, wound up being specifically issued to tank crews and paratroops, where its compactness was a significant advantage.

The Reising developed a quite bad reputation in the Pacific for a couple of reasons. Its parts were not always interchangeable between guns (a deliberate choice to speed up manufacture, which troops were not necessarily aware of), its mechanism was more susceptible to fouling than other military small arms, and its disassembly procedure was far too complex for military service. However, these issues did not prevent it from being quite successful and well-liked as a law enforcement weapon in civilian police use after the war. Thanks to that negative wartime reputation, Reisings are some of the least expensive military machine guns available on the market today in the US.

(more…)

February 13, 2023

Reising M55 Submachine Gun

QotD: Oaths in pre-modern cultures

First, some caveats. This is really a discussion of oath-taking as it existed (and exists) around the Mediterranean and Europe. My understanding is that the basic principles are broadly cross-cultural, but I can’t claim the expertise in practices south of the Sahara or East of the Indus to make that claim with full confidence. I am mostly going to stick to what I know best: Greece, Rome and the European Middle Ages. Oath-taking in the pre-Islamic Near East seems to follow the same set of rules (note Bachvarova’s and Connolly’s articles in Horkos), but that is beyond my expertise, as is the Middle East post-Hijra.

Second, I should note that I’m drawing my definition of an oath from Alan Sommerstein’s excellent introduction in Horkos: The Oath in Greek Society (2007), edited by A. Sommerstein and J. Fletcher – one of the real “go-to” works on oath-taking in the ancient Mediterranean world. As I go, I’ll also use some medieval examples to hopefully convince you that the same basic principles apply to medieval oaths, especially the all-important oaths of fealty and homage.

(Pedantry note: now you may be saying, “wait, an introduction? Why use that?” As of when I last checked, there is no monograph (single author, single topic) treatment of oaths. Rather, Alan Sommerstein has co-authored a set of edited collections – Horkos (2007, with J. Fletcher), Oath and State (2013, with A. Bayliss) and Oaths and Swearing (2014, with I. Torrance). This can make Greek oaths a difficult topic to get a basic overview of, as opposed to a laundry list of the 101 ancient works you must read for examples. Discussions of Roman oaths are, if anything, even less welcoming to the beginner, because they intersect with the study of Roman law. I think the expectation has always been that the serious student of the classics would have read so many oaths in the process of learning Latin and Greek to develop a sort of instinct for the cultural institution. Nevertheless, Sommerstein’s introduction in Horkos presents my preferred definition of the structure of an oath.)

Alright – all of the quibbling out of the way: onward!

So what is an Oath? Is it the same as a Vow?

Ok, let’s start with definitions. In modern English, we often use oath and vow interchangeably, but they are not (usually) the same thing. Divine beings figure in both kinds of promises, but in different ways. In a vow, the god or gods in question are the recipients of the promise: you vow something to God (or a god). By contrast, an oath is made typically to a person and the role of the divine being in the whole affair is a bit more complex.

(Etymology digression: the word “oath” comes to us by way of Old English āþ (pronounced “ath” with a long ‘a’) and has close cousins in Dutch “Eed” and German “Eid”. The word vow comes from Latin (via Middle English, via French), from the word votum. A votum is specifically a gift to a god in exchange for some favor – the gift can be in the present tense or something promised in the future. By contrast, the Latin word for oath is ius (it has a few meanings) and to swear an oath is the verb iuro (thus the legal phrase “ius iurandum” – literally “the oath to be sworn”). This Latin distinction is preserved into the English usage, where “vow” retains its Latin meaning, and the word “oath” usurps the place of Latin ius (along with other words for specific kinds of oaths in Latin, e.g. sacramentum)).

In a vow, the participant promises something – either in the present or the future – to a god, typically in exchange for something. This is why we talk of an oath of fealty or homage (promises made to a human), but a monk’s vows. When a monk promises obedience, chastity and poverty, he is offering these things to God in exchange for grace, rather than to any mortal person. Those vows are not to the community (though it may be present), but to God (e.g. Benedict in his Rule notes that the vow “is done in the presence of God and his saints to impress on the novice that if he ever acts otherwise, he will surely be condemned by the one he mocks“. (RB 58.18)). Note that a physical thing given in a vow is called a votive (from that Latin root).

(More digressions: Why do we say “marriage vows” in English? Isn’t this a promise to another human being? I suspect this usage – functionally a “frozen” phrase – derives from the assumption that the vows are, in fact, not a promise to your better half, but to God to maintain. After all, the Latin Church held – and the Catholic Church still holds – that a marriage cannot be dissolved by the consent of both parties (unlike oaths, from which a person may be released with the consent of the recipient). The act of divine ratification makes God a party to the marriage, and thus the promise is to him. Thus a vow, and not an oath.)

So again, a vow is a promise to a divinity or other higher power (you can make vows to heroes and saints, for instance), whereas an oath is a promise to another human, which is somehow enforced, witnessed or guaranteed by that higher power.

An example of this important distinction being handled in a very awkward manner is the “oath” of the Night’s Watch in Game of Thrones (delivered in S1E7, but taken, short a few words, verbatim from the books). The recruits call out to … someone … (they never name who, which as we’ll see, is a problem) to “hear my words and bear witness to my vow”. Except it’s not clear to me that this is a vow, so much as an oath. The supernatural being you are vowing something to does not bear witness because they are the primary participant – they don’t witness the gift, they receive it.

I strongly suspect that Martin is riffing off of here are the religious military orders of the Middle Ages (who did frequently take vows), but if this is a vow, it raises serious questions. It is absolutely possible to vow a certain future behavior – to essentially make yourself the gift – but who are they vowing to? The tree? It may well be “the Old Gods” who are supposed to be both nameless and numerous (this is, forgive me, not how ancient paganism worked – am I going to have to write that post too?) and who witness things (such as the Pact, itself definitely an oath, through the trees), but if so, surely you would want to specify that. Societies that do votives – especially when there are many gods – are often quite concerned that gifts might go awry. You want to be very specific as to who, exactly, you are vowing something to.

This is all the more important given that (as in the books) the Night’s Watch oath may be sworn in a sept as well as to a Weirwood tree. It wouldn’t do to vow yourself to the wrong gods! More importantly, the interchangeability of the gods in question points very strongly to this being an oath. Gods tend to be very particular about the votives they will receive; one can imagine saying “swear by whatever gods you have here” but not “vow yourself to whatever gods you have here”. Who is to say the local gods take such gifts?

Moreover, while they pledge their lives, they aren’t receiving anything in return. Here I think the problem may be that we are so used to the theologically obvious request of Christian vows (salvation and the life after death) that it doesn’t occur to us that you would need to specify what you get for a vow. But the Old Gods don’t seem to be in a position to offer salvation. Votives to gods in polytheistic systems almost always follow the do ut des system (lit. “I give, that you might give”). Things are not offered just for the heck of it – something is sought in return. And if you want that thing, you need to say it. Jupiter is not going to try to figure it out on his own. If you are asking the Old Gods to protect you, or the wall, or mankind, you need to ask.

(Pliny the Elder puts it neatly declaring, “of course, either to sacrifice without prayer or to consult the gods without sacrifice is useless” (Nat. Hist. 28.3). Prayer here (Latin: precatio) really means “asking for something” – as in the sense of “I pray thee (or ‘prithee’) tell me what happened?” And to be clear, the connection of Christian religious practice to the do ut des formula of pre-Christian paganism is a complex theological question better addressed to a theologian or church historian.)

The scene makes more sense as an oath – the oath-takers are swearing to the rest of the Night’s Watch to keep these promises, with the Weirwood Trees (and through them, the Old Gods – although again, they should specify) acting as witnesses. As a vow, too much is up in the air and the idea that a military order would permit its members to vow themselves to this or that god at random is nonsense. For a vow, the recipient – the god – is paramount.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Oaths! How do they Work?”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2019-06-28.

February 12, 2023

JunkScientific American

The editors of Scientific American have been steadily injecting more political and progressive content into their traditional coverage of hard scientific topics:

Scientific American magazine has been around since 1845, evolving into a reader-friendly purveyor of hard science, a respected, slightly intimidating denizen of supermarket checkout lines. But judging by the recent ridiculous trend of stories and editorials, it’s been wholly captured by the woke blob.

On the surface the monthly still does what it says on the label in providing long articles, short reviews, and cool photographs for an intelligent audience, with almost-comprehensible stories on the physics of black holes for science buffs, and stunning photos of deep-sea creatures for the rest of us.

But then there’s the ludicrously left-wing ideology that seeps into every issue. A NewsBusters perusal of the contents of each 2022 regular-release monthly issue revealed 34 stories grounded in liberal assumptions and beliefs, nearly three per issue. That’s even after skipping stories with liberal themes that were nonetheless science-based — for example, a cover story on melting glaciers in Antarctica wasn’t included.

Of course, the COVID pandemic in particular tugged the magazine toward government interventionism and the smug rule of health “experts”.

Some of the most bizarrely “woke” material is online-only, with a wider potential reach. The most notorious recent example is a January 6, 2023 opinion piece, cynically seizing on the on-field collapse of a Buffalo Bills player to label the NFL racist: “Damar Hamlin’s Collapse Highlights the Violence Black Men Experience in Football — The “terrifyingly ordinary” nature of football’s violence disproportionately affects Black men“. It’s written by Tracie Canada, who is, no surprise, an assistant professor of cultural anthropology.

So what’s the solution? Surely Canada wouldn’t recommend banning blacks from the National Football League for their own protection?

But plenty of bizarre pieces fill the print edition. Here’s a headline from the July 2020 issue of this purported science magazine: “The Racist Roots of Fighting Obesity“. Yet a June 2019 SA article argued that the nation’s “biggest health problem” was obesity. So is Scientific American, for being concerned about obesity, by its own bizarre standard racist as well?

German Desperation in Korsun Pocket – Week 233 – February 11, 1944

World War Two

Published 11 Feb 2023It is crisis mode in the Korsun Pocket this week for the Axis troops surrounded, but they are also losing ground all over the Eastern Front this week, including the big prize of Nikopol. In Italy, it is a different story as the Germans play offense at Anzio, though with only small gains.

(more…)

When the institutions are failing, we must depend on the individuals

Chris Bray wraps up several earlier posts here in “Victory in the Moments”:

We see the implosion of a country that has worked well, and of a culture that has worked well. We see that things that have worked are moving hard toward being things that don’t work. Marriage and family connections are declining sharply, birthrates are plummeting, Americans are surviving on their credit cards, colleges provide increasingly little education at an increasingly absurd cost, a staggeringly expensive military is becoming functionally ineffective, public health measures reverse the health of the public. See also Darren Beattie on the Ricky Vaughn trial, or Vincent Floyd’s description of teaching woke students as a black professor who got the full Cultural Revolution treatment, or the FBI’s intel memo warning that traditional Catholicism is terrorism-adjacent, or the disgusting whistleblower revelations coming out of the evil human slaughterhouse of a pediatric gender-affirmation clinic, or Christopher Buskirk’s essay on “An Age of Decay”. Yes: evil prevails, and decline is here.

In response, the national political class and its courtiers in the “mainstream” political press offer Dr. Seuss stories like BUZZ GROWS AROUND KLOBUCHAR, completely meaningless gibbering that doesn’t have anything to do with anything. Clearly, no help is coming, and no rescue operation is being organized. Institutions are fully self-interested, working solely on capturing their share of a shrinking pie. Financialization and performativity prevail over operational function.

However.

I wrote earlier this week about the recent appearance of startling runway near-misses, and about a warning from a longtime pilot that those kinds of incidents are becoming more common. But wind the tape back a bit: Commercial aviation is emerging from, or arguably still in, a long-period of historically astonishing safety. You’ll find a chart here of safety data from US airlines over the last couple of decades. That number in the center with the decimal point represents fatal accidents per 100,000 departures:

Why?

Flying is inherently dangerous; the early American pilot Ernest Gann, who flew mail routes by dropping out of the clouds to look for highway intersections with a road map on his lap (and navigated from California to Hawaii by flying an azimuth, counting elapsed hours, and checking his math with a sextant), titled his memoirs Fate is the Hunter, and opened the book with a pages-long dedication to all of his dead colleagues.

Politics didn’t solve much of anything. The long path to shockingly safe commercial aviation mostly didn’t pass through Congress, though they’d probably be willing to take credit for it. Flying didn’t become safer because Elizabeth Warren said so. Instead, pilots got better at teaching pilots how to fly safely, and working together as crews, and airlines developed better maintenance practices, and airports and airlines improved technology and procedures. Researchers and regulators played a significant role, but pilots didn’t work on making flying safer because the government made them — they made flying safer so they’d be less likely to kill people, in an expression of professionalism and craft. The airline industry adopted CRM, and then later the FAA mandated it.

Who made commercial aviation safe? Tens of thousands of pilots and mechanics and airline managers and air traffic controllers and ramp managers and marshallers, practitioners who did their work with focus and care. To a significant degree, individual pride and diligence, aggregated into the way airlines work, made commercial aviation safe. Regulators and investigators policed the margins, catching bad practices, but they didn’t make the culture of professionalism in aviation.

Avro Vulcan: What made the Vulcan the best V bomber?

Imperial War Museums

Published 28 Apr 2021The Avro Vulcan Bomber, the most famous of the British V bombers, is known for its distinctive howl and delta wing. Initially one of the delivery agents of Britain’s independent nuclear deterrent during the Cold War, the Vulcan later fulfilled another role, undertaking the longest bombing raid in history for Operation Black Buck in the Falklands Campaign of 1982. One of the first operational RAF aircraft with a delta wing, this impressive Cold War jet has never lost its appeal. In this video, events and experiences coordinator Liam Shaw takes us through the extraordinary history and technological achievements of the Avro Vulcan. We go into the cockpit and hear first-hand from the people who flew this unique machine throughout its long and remarkable history.

(more…)

QotD: The heyday of Victorian newspapers

A few years ago, I did some research on three early Victorian murders that caused me to read several provincial newspapers of the time. I discovered incidentally to my research that the owners or editors of about half of the British provincial newspapers also sold patent medicines; and this made perfect sense, for by far the greatest advertisers in provincial newspapers were the manufacturers of patent medicines. The owners or editors of the newspapers sold advertisements to the producers of patent medicines, then they sold the newspapers in which the advertisements appeared, and finally they sold the products themselves to the readers. It was an excellent example of rational commercial synergy. (About half of the medicines, by the way, were either to cure or to prevent syphilis — a disease, then, that was a great support to the press of the time.)

Now, the principal quality or characteristic of the sellers of patent medicine has always been effrontery, that is to say the blatant insinuation of the false. Thomas Holloway’s innovation was to insinuate such falsehood on a mass or industrial scale. There was hardly a newspaper in which he did not place a weekly advertisement; moreover, he pioneered the advertisement that masquerades as news story. He would ensure that reports of miracle cures in faraway places, supposedly wrought by his pills and ointment, and written as matter-of-factly as possible, were placed in every newspaper, reports whose veracity no one could possibly check for himself, of course.

As Napoleon once said, repetition is the only rhetorical technique that really works — besides which hope and fear render people susceptible to effrontery. In Thomas Holloway’s time, the fear of illness was often, and the hope of cure rarely, justified; at least Holloway’s preparations were unlikely to do much harm (they contained aloe, myrrh, and saffron), unlike the prescriptions of the orthodox doctors of the time. They allowed for the possibility of natural recovery, whereas orthodox medicine often hurried its consumers into their graves. Nevertheless, the claims Holloway made for his ointment and pills were preposterous, and something is not curative just because it fails to kill.

Holloway made an immense fortune by his effrontery and founded a women’s college in the University of London on the proceeds.

Theodore Dalrymple, “The Way of Che”, Taki’s Magazine, 2017-10-28.

February 11, 2023

Americans tend to think other countries are just like America, but with weird accents and quaint clothing

Sarah Hoyt on the common problem Americans (and to a lesser extent, Canadians) have in trying to understand other nations even if they’ve done some international travel:

I also see every country, regardless of their history making the assumption that the modus operandi and motives of other cultures and organizations is exactly the same as theirs. I’ve now mentioned about a million times the idiots who went over as Human Shields to Iraq because “they can’t even provide drinking water for their people, how would they have missiles” thereby completely missing the fact that other countries — dictatorships at that — have different priorities than say the US or England, even. In the same way, Portugal assumes that every country is as fraught as corruption as they are. Which works fine for other Latin countries, but fails them when it comes to other places, because as corrupt as we are … yeah. It’s nowhere near there yet. Russia assumes everyone moves, breathes and thinks only about them, and that everyone’s intention is to threaten them or conquer them, because they are obsessed with their dreams of national glory, and they think they should rule the world. And the US by and large goes around like a large vaguely autistic child who really, really, really doesn’t understand how different it is from other nations, or if it does assumes it’s worse.

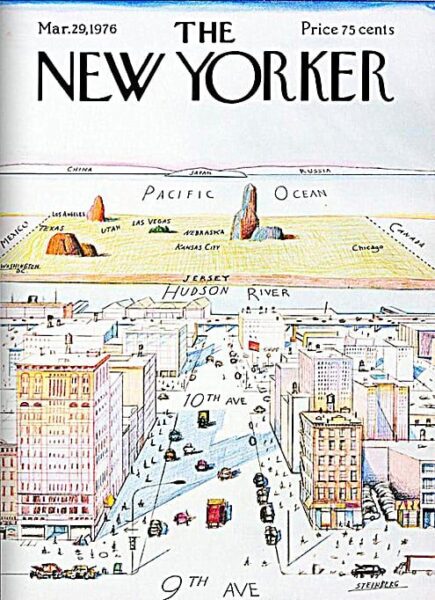

Look, it’s part of the reason our intelligence services are so sucky. To completely understand what other countries are doing and why, you have to know they have very different cultures. They’re not you. Most countries can sort of extrapolate other countries, but America is so different we suck at it. This is why we tend to think places like the USSR (Russia’s party mask) were totes super powers. Because for America to do and say the things they did and said, we’d have to be very sure of our power. But other countries aren’t America. So we go through the world acting like gullible giants.

In fact Americans have one of the weirder cultures in the world. It’s just not in your face weird as China (whose history reads like they should be extra-terrestrials.) It’s subtle and more in the mental furniture.

Because of this, and because we’re a continent-sized nation, born and bred Americans (as opposed to imports like me) read not just the rest of the world but history hilariously wrong. (The history part is because at least when I went through school here — one year — American schools suck at teaching history. It’s all names and dates, not “Why did France do that?” Yeah, probably not worse than the rest of the world, now that all the books have just-so Marxist explanations, but still stupid.)

I had friends in my writers’ group back when who were writing, say, ancient Egyptian families and couldn’t understand in most of them the teens wouldn’t be/act the same as American teens now. Heck, my dad’s generation in Portugal, less than 100 years ago weren’t “teens” really. Their equivalent was under ten. Because by 12 most of the boys in the village were apprenticed in the job they’d have for life. (And dad was in school, yes, but it was way tougher than even I had.) They didn’t have time. And even I — and you guys know my basic disposition — didn’t sass my parents as American teens do, because there was a deep “fund” of “respect the elders” in the culture. I still have trouble calling people older than I — even colleagues — by their first name.

And then there’s the hilarious — or sad — misunderstandings like the Human Shields mentioned above. It’s sad, because they will buy other countries at face value, but are willing to entertain their own country might be evil. Which is why we have a large contingent of open-mouth guppies who think that the US invented slavery. Even though places around the world still have slavery. Including China, where everyone is a slave, it’s the degree that varies, of course.

The problem is made worse — not better — by idiotic travel abroad.

To understand the differences in a country, you need to live with them, as one of them, for a while. You need to speak the language well enough you understand overheard conversations. Etc.

My experience coming over as an exchange student for 12th grade was about ideal. I lived with an American family, as one of their kids, and attended a school nowhere USA (okay, a suburb of Akron, Ohio) and yeah, I had slight celebrity status in the school — being one of three foreign exchange students — but not that much. So I got to experience the normal life of normal people in normal circumstances, which was an eye-opener.

I always wanted my kids to follow me in this experience, but you know, things got complicated around the time they were of age to do it. So they didn’t. They still have experienced life as an every day foreigner when we visit my parents. In fact the issue there is that they never get past the irritation “What do you mean we can’t do that” and towards “oh, it’s just different. Still sucky, but different.”

Going over for two weeks, with or without the guided tour, staying in nice hotels and associating only with people at your social level and not past the level of polite interaction does not enlarge the mind. Instead, it gives a false sense of knowing what the world is like. This is where we get the “socialists” who know it’s good, because look at all the magnificent buildings in Europe, and the fact everyone has time to sit in the coffee shop and socialize with friends. And look at all the amazing public transportation. And and and. If you lived there, or knew history, you’d know most of the buildings created by socialists in the 20th and 21st century are already crumbling. (Some start before being finished.) You’d know people sit around in coffee shops either because they are unemployed, they pretend to work and their boss pretends to pay them, or all of the above. And all of it is paid for in a significant reduction in lifestyle and just the general comfort of life. (Take it from me. Their lifestyle is two social economic levels down from us, for the same relative “income level.” So, you know, upper class is middle-middle class here.) And you’d know the frustration of waiting for the bus on a rainy, windy day, getting soaked, but the bus is late because all the bus drivers went out for a pint together. And suddenly there’s five of them in a row, but you’re already soaked and starting to cough. More importantly you’d know the public transport only works because everyone works in the city and lives in crowded suburbs, in stack-a-prole apartments, while the countryside is relatively empty. And the people who live there need to buy gas at ridiculous prices, so they can barely afford it.

Napoleon’s Downfall: Why He Lost the Battle of Nations

Real Time History

Published 10 Feb 2023After the brief summer 1813 cease fire, Napoleon’s campaign in Germany resumes. Surrounded by the Allies — which also manage to slowly turn the tide at Großbeeren, Dennewitz, Kulm, and Dresden — his only remaining option is the ultimate battle which takes place in October 1813 at Leipzig: The Battle of Nations.

(more…)

As predicted, HarperCollins’ fit of irrational exuberism has come to an unprofitable end

In the latest SHuSH newsletter, Ken Whyte refers back to HarperCollins and the predicted outcome of taking the one-off sales bonanza of peak pandemic and expecting those numbers to continue once the lockdowns eased:

Book sales spiked during the pandemic and no one enjoyed the ride more than HarperCollins CEO Brian Murray. In June 2021, with his revenue up 19% and his profits up 45 percent, Murray opened the taps:

We are being aggressive in terms of buying books. We’ve seen the book pie grow maybe 15 percent and so our response, which is part opportunist, part defensive, is to be aggressive in buying right now. Because if that pie remains large, we want to make sure that we get a nice share of the larger pie. And if it happens to wane a little bit, we want to make sure that we have a lot of new, exciting books for the future that will maintain our revenues at the current levels. So we’ve been very aggressive over the last six to nine months in trying to sign up the best books that we see in the marketplace.

Murray not only bought more books than usual, he paid more than usual. I read his comments at the time and called my buddy, ECW founder Jack David, who, in his half century in the business, has seen everything. Jack’s response: “Don’t do it!”

Jack and I agreed (see SHuSH 103) that even if Murray acquired a lot of good titles, revenues would disappoint in 2022 and beyond. The publishing pie hadn’t grown. It was temporarily inflated by the unusual and temporary circumstances of the pandemic. Inevitably, life would return to some semblance of normal and aggregate demand for books would revert to the mean. “Twelve months from now,” wrote SHuSH, “Murray will be out of range of 2021’s windfall profits, and perhaps worried about losing money. That’s when the cutting begins.”

We promised at the time to check back to discuss “the great publishing contraction of 2022”.

It’s been eighteen months and the great publishing contraction is now upon us.

Here are the last six months of 2022 according to the Association of American Publishers: July, down 14.9 percent from the previous year; August, down 9 percent; September, down 4.5 percent; October, down 9.3 percent; November, down 6 percent. December should be reported in a week or two. It, too, will be down something.

Another data source is NPD BookScan, which estimates book sales were down 6.5 percent in 2022 compared to 2021.

Give Brian Murray credit for at least being first among his colleagues to react to these new circumstances. He announced last week that he will be cutting 5 percent of his North American work force because the sales surge enjoyed during the pandemic has “slowed significantly as of late.” His note to staff said “we must pause to recognize the depth of the core issues we currently face”. He pointed directly at “unprecedented supply chain and inflationary pressures … increasing paper, manufacturing, labor, and distribution costs”. The company has been raising prices and cutting costs since last fall (so maybe our timing wasn’t off), but “more needs to be done”.

More indeed. Unfortunately. Book sales in 2022 may have been down from 2021 levels but they’re still 11.8 percent above 2019, the pre-pandemic year, suggesting the correction is not finished. Meanwhile, economists say there’s a 70 percent chance of a recession this year. Let’s hope they’re wrong or, at minimum, that any downturn will be shallow and quick.

Tank Chats #167 | French Panhard EBR | The Tank Museum

The Tank Museum

Published 28 Oct 2022How much do you know about the Panhard EBR? Join David Willey for this week’s Tank Chat as he covers the development, design and use of this French armoured car.

(more…)

QotD: “The rest of philosophy is not, as Alfred North Whitehead would have it, a series of footnotes to Plato … but all secular religions are”

Which is why I’m not going to humbug you about “the Classics.” Commanding you to “read the Classics!” would do you more harm than good at this point, because you have no idea how to read the Classics. Context is key, and nobody gets it anymore. Back when, that’s why they required Western Civ I — since all the Liberal Arts tie together, you needed to study the political and social history of Ancient Greece in order to read Plato (who in turn deepened your understanding of Greek society and politics … and our own, it goes without saying). I can’t even point you to a decent primer on Plato’s world, since all the textbooks since 1985 have been written by ax-grinding diversity hires.

And Plato’s actually pretty clear, as philosophers go. You’d really get into trouble with a muddled writer … or a much clearer one. A thinker like Nietzsche, for example, who’s such a lapidary stylist that you get lost in his prose, not realizing that he’s often saying the exact opposite of what he seems to be saying. To briefly mention the most famous example: “God is dead” isn’t the barbaric yawp of atheism triumphant. The rest of the paragraph is important, too, especially the next few words: “and we have killed him.” Nietzsche, supposedly the greatest nihilist, is raging against nihilism.

[…]

So here’s what I’d do, if I were designing a from-scratch college reading list. I’d go to the “for Dummies” versions, but only after clearly articulating the why of my reading list. I’d assign Plato, for example, as one of the earliest and best examples of one of mankind’s most pernicious traits: Utopianism. The rest of philosophy is not, as Alfred North Whitehead would have it, a series of footnotes to Plato … but all secular religions are. The most famous of these being Marxism, of course, and you’d get much further into the Marxist mindset by studying The Republic than you would by actually reading all 50-odd volumes of Marx. “What is Justice?” Plato famously asks in this work; the answer, as it turns out, is pretty much straight Stalinism.

How does he arrive at this extraordinary, counter-intuitive(-seeming) conclusion? The Cliff’s Notes will walk you through it. Check them out, then go back and read the real thing if the spirit moves you.

Articulating the “why” saves you all kinds of other headaches, too. Why should you read Hegel, for example? Because you can’t understand Marx without him … but trust me, if you can read The Republic for Dummies, you sure as hell don’t have to wade through Das Kapital. Marxism was a militantly proselytizing faith; they churned out umpteen thousand catechisms spelling it all out … and because they did, there are equally umpteen many anti-Marxist catechisms. Pick one; you’ll get all the Hegel you’ll ever need just from the context.

Severian, “How to Read ‘The Classics'”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2020-02-13.

February 10, 2023

When “Taffy 3” kicked the ass of the pride of the Imperial Japanese Navy

Chris Bray isn’t a milblogger, but I thought his summary of the Battle of Leyte Gulf was pretty darned good:

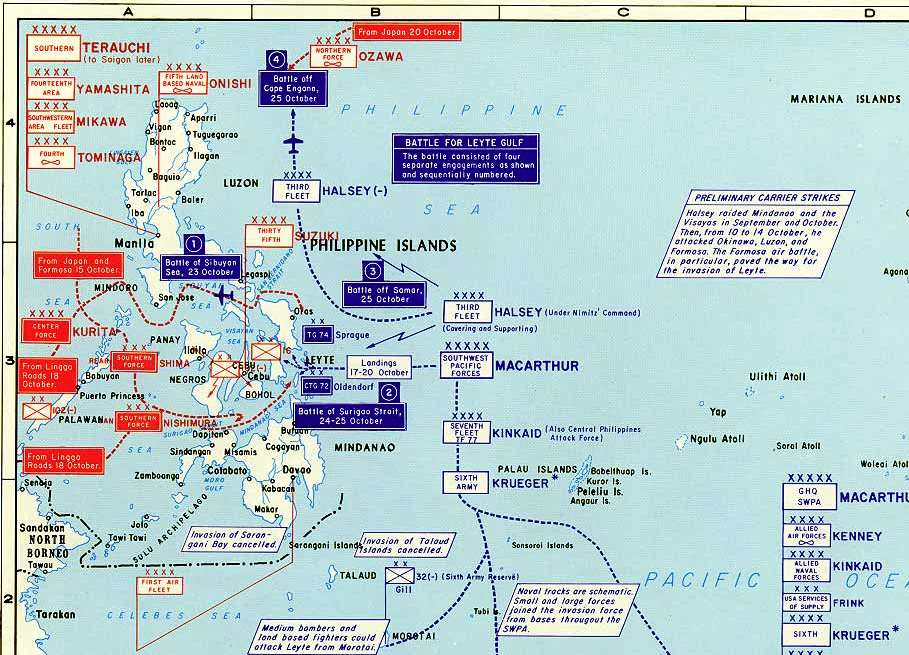

In October of 1944, US troops landing on Leyte Island in the Philippines were menaced from the sea by an enormous Japanese naval fleet that was divided into three separate attack forces.

Detail of the West Point Military Atlas: World War II: Asia-Pacific Invasion of Leyte, October 1944 map.

https://www.westpoint.edu/sites/default/files/inline-images/academics/academic_departments/history/WWII%20Asia/ww2%2520asia%2520map%252029.jpgSummarizing aggressively, the American ground forces were protected against an attack from the sea by the US Navy’s Third Fleet, commanded by Bull Halsey. But Halsey suddenly wasn’t there anymore, taking the bait of a decoy attack force [of de-planed Japanese carriers] and chasing it out into the sea. The Third Fleet’s departure uncovered Leyte Gulf, and the largest of the Japanese attack forces sailed in. Disaster became likely.

There were two American naval task forces in the path of the Japanese attack force, Taffy 2 and Taffy 3, but neither were meant for serious naval combat. They were supporting forces, designed to help the troops on the ground: a few escort carriers, a few lightly armed destroyer escorts, a very few destroyers. Aircraft on the American escort carriers were armed with 100-pound bombs to provide close air support to the infantry. The Japanese First Task Force had four battleships, eight cruisers, and eleven destroyers. One of the Japanese battleships was the Yamato, armed with 18-inch guns. The Japanese attack force sailed directly into contact with Taffy 3, which didn’t realize they were about to face the main Japanese attack force until they were already within range of its guns.

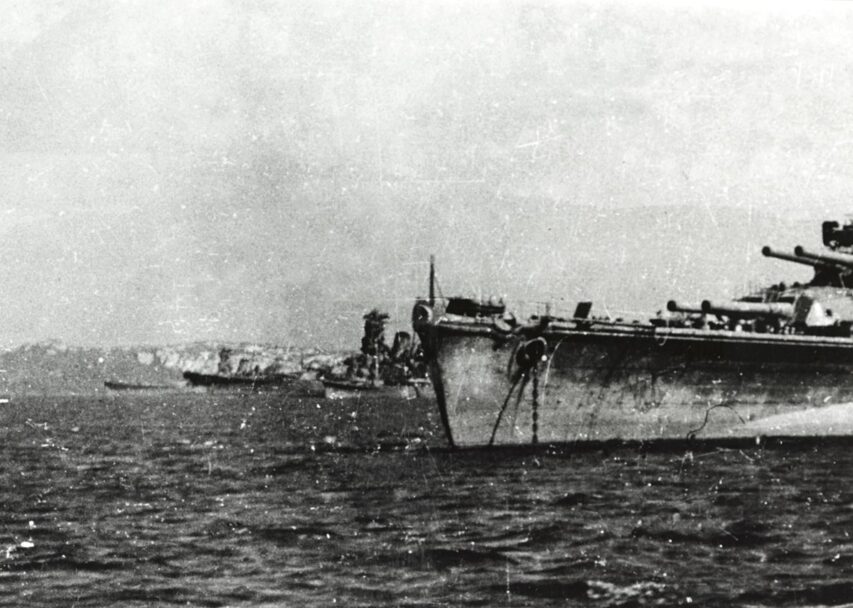

Imperial Japanese Navy ships at anchor in Brunei, Borneo shortly before the Battle of Leyte Gulf. Left to right, Musashi, Yamato, an unidentified cruiser, and Nagato.

Photo by Kazutoshi Hando from the US Naval History and Heritage Command collection.The commander of Taffy 3, Rear Admiral Clifton Sprague, saw immediately that his task force couldn’t survive the engagement, so he tried to salvage what he could: He ordered his destroyers and destroyer escorts to attack, to cover the hoped-for withdrawal of the escort carriers. The resulting battle is one of the best-known in naval history — and one of the least plausible, because Taffy 3 kicked the everloving shit out of that much larger Japanese attack force, compelling the Japanese to withdraw in the panicked belief that they’d sailed into the bulk of Halsey’s Third Fleet.

If you haven’t read [the late] James Hornfischer’s magnificent book about the battle, The Last Stand of the Tin Can Sailors, you should read it. The details are far beyond anything that could be summarized in a single short piece. But the battle was won by a remarkable combination of disciplined obedience, independent audacity, and a paradoxically disciplined disobedience — by men aggressively refusing to obey orders that threatened their cause.

The Fletcher-class destroyer USS Johnston (DD-557), sunk in the Battle off Samar, 25 October, 1944.

US Navy photo with enhancement work by Wild Surmise via Wikimedia Commons.The battle began with one of the US Navy’s most famous moments. Before Sprague had time to order anyone to do anything, the captain of the Johnston, one of Taffy 3’s few destroyers, turned to attack the Japanese fleet. We have confused and contradictory accounts of the orders given by Cmdr. Ernest Evans, because the man who gave them, and most of the men who heard them, died soon afterward, but he is supposed to have said something like this:

1.) We’re under the guns of a much larger Japanese fleet.

2.) Survival is not to be expected.

3.) Hard left rudder, all ahead flank.

We’re all going to die; attack. The Johnston sank, and Evans died, but his first torpedo run blew the bow off a Japanese cruiser — setting the tone of the fight.

Hitler’s Jazz Band – WW2 Documentary Special

World War Two

Published 9 Feb 2023Does Adolf Hitler like Duke Ellington? No, and nor do many National Socialists. But the story of the music in the Third Reich is more complicated than you might think. What if we told you that Joseph Goebbels has tried to create a Nazi-approved swing band tasked with bringing the Jazz War to the Allies?

(more…)

“What’s happening to children is morally and medically appalling”

In The Free Press, Jamie Reed explains why she gave up her job as as a case manager at The Washington University Transgender Center at St. Louis Children’s Hospital and is now speaking out against the early and aggressive therapeutic treatment of gender-confused children and teens:

Soon after my arrival at the Transgender Center, I was struck by the lack of formal protocols for treatment. The center’s physician co-directors were essentially the sole authority.

At first, the patient population was tipped toward what used to be the “traditional” instance of a child with gender dysphoria: a boy, often quite young, who wanted to present as — who wanted to be — a girl.

Until 2015 or so, a very small number of these boys comprised the population of pediatric gender dysphoria cases. Then, across the Western world, there began to be a dramatic increase in a new population: Teenage girls, many with no previous history of gender distress, suddenly declared they were transgender and demanded immediate treatment with testosterone.

I certainly saw this at the center. One of my jobs was to do intake for new patients and their families. When I started there were probably 10 such calls a month. When I left there were 50, and about 70 percent of the new patients were girls. Sometimes clusters of girls arrived from the same high school.

This concerned me, but didn’t feel I was in the position to sound some kind of alarm back then. There was a team of about eight of us, and only one other person brought up the kinds of questions I had. Anyone who raised doubts ran the risk of being called a transphobe.

The girls who came to us had many comorbidities: depression, anxiety, ADHD, eating disorders, obesity. Many were diagnosed with autism, or had autism-like symptoms. A report last year on a British pediatric transgender center found that about one-third of the patients referred there were on the autism spectrum.

Frequently, our patients declared they had disorders that no one believed they had. We had patients who said they had Tourette syndrome (but they didn’t); that they had tic disorders (but they didn’t); that they had multiple personalities (but they didn’t).

The doctors privately recognized these false self-diagnoses as a manifestation of social contagion. They even acknowledged that suicide has an element of social contagion. But when I said the clusters of girls streaming into our service looked as if their gender issues might be a manifestation of social contagion, the doctors said gender identity reflected something innate.

To begin transitioning, the girls needed a letter of support from a therapist — usually one we recommended — who they had to see only once or twice for the green light. To make it more efficient for the therapists, we offered them a template for how to write a letter in support of transition. The next stop was a single visit to the endocrinologist for a testosterone prescription.

That’s all it took.

When a female takes testosterone, the profound and permanent effects of the hormone can be seen in a matter of months. Voices drop, beards sprout, body fat is redistributed. Sexual interest explodes, aggression increases, and mood can be unpredictable. Our patients were told about some side effects, including sterility. But after working at the center, I came to believe that teenagers are simply not capable of fully grasping what it means to make the decision to become infertile while still a minor.