Rex Krueger

Published 16 Oct 2019More video and exclusive content: http://www.patreon.com/rexkrueger

Get plans, t-shirts, and hoodies: http://www.rexkrueger.com/store

See all the stuff you can get at a big show: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dm435…

(more…)

October 17, 2019

Pro Tips for Tool Hunting at Flea Markets

England in 1550 was a remarkably unpromising location for the later industrial revolution

Anton Howes, in his investigations on the Industrial Revolution looks back in time to see where or even if England deviated from the rest of Europe in ways that made the revolution possible, thinks he’s located the crucial time:

If a peaceful extraterrestrial visited the world in 1550, I often wonder where it would see as being the most likely site of the Industrial Revolution – an acceleration in the pace of innovation, resulting in sustained and continuous economic growth. So many theories about why it happened in Britain seem to have a sense of inevitability about them, but our extraterrestrial visitor would have found very few signs that it would soon occur there. There were many better candidates, on a multitude of metrics.

[…]

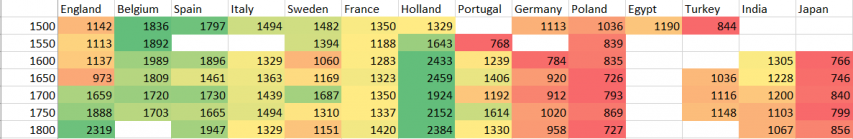

But England in 1550 was by global standards quite poor. Historical GDP per capita measures are notoriously difficult to obtain, even for some countries in the twentieth century let alone the sixteenth. The historical GDP per capita of England – by far the most studied region – is still hotly debated among economic historians. Nonetheless, according to the most recent collection of estimates – the Maddison project’s database of 2018 – in 1550 our extraterrestrial visitor would have been much more interested in Belgium. England at that stage lagged behind almost all of the areas for which we have estimates: Holland, Spain, Italy, Sweden, and France. In 1600, it was behind Portugal and India. Here are the figures in 2011 dollars; the colours are by row:

Such estimates should of course be taken with a hefty boulder of salt. (Note, also, that these particular figures, called “CGDPpc”, are something of an innovation by the team compiling the Maddison Project Database – they use multiple benchmarks to improve how we compare countries’ relative incomes in any particular year, which comes at the cost of not being able to compare their growth rates, for which there are separate figures. In other words, you should read the figures by row, not by column.) But it is worth noting that the more recent research on historical GDP per capita, finally filling in some details for regions other than England and Holland, often results in those other countries seeming richer in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The more we know, the more the traces of an early English divergence seem to disappear.

Even without access to such statistics, however, our visitor would have noticed that in the mid-1550s England suffered severe food shortages. Indeed, the threat of famine would be present right up until the beginning of the eighteenth century: there was a major famine in the north of England in 1649, and even a famine in the 1690s that killed between five and fifteen percent of Scotland’s population. Britain would one day become perhaps the first famine-free region, but that did not occur until much later, when innovation had already begun to accelerate. It may even have been its result.

And England in 1550 was not just poor; it was also weak. If our visitor thought, as some historians do, that conquest and exploitation were essential for future growth, then it was Spain that had the major overseas empire, followed by Portugal. England in 1550 had no colonies in the New World, and its attempts to found them all failed until the seventeenth century, by which stage the Dutch and French had also begun to extend their own empires too. It was not until the eighteenth century that Britain began to exceed them.

American Eagle Lugers

Forgotten Weapons

Published on 1 Dec 2014

Dissent This

Sold for $14,950 (9mm fat barrel) and $9,775 (7.65mm test trials).Many people are aware of the .45 caliber Lugers made for US military field trials — but far fewer people realize that Lugers were both tested by the US military and sold commercially several years prior to the .45 tests.

In 1900, the US military put several hundred 7.65mm Luger pistols into field trials with both infantry and cavalry units. These pistols were marked with a large and elaborate American eagle crest, in an attempt by DWM to enhance the gun’s appeal to Americans. A similar tactic was used in production of Lugers for Swiss sale, with a large Swiss cross (and it worked well).

After complaints about the small caliber of the early 1900 Lugers, DWM developed the 9mm Parabellum cartridge, and attempted to sell them commercially in the US (and elsewhere). A small batch were also purchased for further military testing.

http://www.forgottenweapons.com

Theme music by Dylan Benson – http://dbproductioncompany.webs.com

QotD: IKEA humans

Therefore, to be precise, the class of people of whom I am speaking are “cosmopolitan” neither in the idealized nor in the demonized sense of the word. They neither bridge deep social differences in search of the best in human experience, nor debase themselves with exotic foreign pleasures. Rather, they have no concept of foreignness at all, because they have no native traditions against which to compare. Indeed, the very idea of a life shaped by inherited custom is alien to our young couple. When Jennifer and Jason try to choose a restaurant for dinner, one of them invariably complains, “I don’t want Italian, because I had Italian last night.” It does not occur to them that in Italy, most people have Italian every night. For Jennifer and Jason, cuisines, musical styles, meditative practices, and other long-developed customs are not threads in a comprehensive or enduring way of life, but accessories like cheap sunglasses, to be casually picked up and discarded from day to day. Unmoored, undefined, and unaware of any other way of being, Jennifer and Jason are no one. They are the living equivalents of the particle board that makes up the IKEA dressers and IKEA nightstands next to their IKEA beds. In short, they are IKEA humans.

Samuel Biagetti, “The IKEA Humans: The Social Base of Contemporary Liberalism”, Jacobite, 2017-09-13.