As a specific genre, the historical novel is only about two centuries old. Historical fiction in the wider sense, though, is at least as old as the written word. The Epic of Gilgamesh, the Homeric poems, the narrative books of the Old Testament, Beowulf — the earliest literature of every people is historical fiction. The past is interesting. It’s glamorous and exciting. Perspective allows us to forget that the past, like the present, was mostly long patches of boredom or anxiety, mixed in with occasional moments of catastrophe or bliss. Above all, it’s about us.

Have you ever stared at old family pictures, and had the feeling that you were looking into a mirror? I have a photograph of a great uncle, who was an old man before I was born. I never knew him well. But in that picture, taken when he was about fifteen, he has my ears and eyes, and he’s hugging himself and looking just as complacent as I often do. I have a picture of one of my grandmothers, taken about the year 1916 — she’s photographed against a background of flags and Dreadnoughts. She looks astonishingly like my daughter. It’s only natural that I want to know about them. I want to know what they were thinking and doing, and I want to know about their general circumstances.

For most people, even now, family history comes to a dead end about three generations back. But we are also members of nations, and what we can’t know about our immediate ancestors we want to know about our ancestors in general. You can take the here and now just as it is. But the moment you start asking why things are as they are, you have to investigate the past.

Why do men wear collars and ties and jackets with buttons that often don’t and can’t do up? It’s because our own formal clothing stands in a direct line from the English and French court dress of the late 17th century. Why do we talk of “toeing the line?” It’s because in 19th century state schools, children would have to stand on a chalked line to read to the class. Why does the British fiscal year for individuals start on the 6th April? It’s because, until 1752, we used the Julian Calendar, which was eleven days behind the more accurate Gregorian Calendar; and the first day of the year was the 25th March. Lord Chesterfield’s Act standardised us with Scotland and much of Europe, and moved the first day of the year back to January — but the fiscal year, adjusted for the new calendar, was left unchanged.

Why was Ireland, until recently, so devoutly Catholic? Because the Catholic Church was the one great institution of Irish life that could be neither abolished nor co-opted by their British rulers. Why is the Church losing its hold? Because it is no longer needed for its old purpose. The child sex scandals are only a secondary cause. History tells us who we are. We may feel trapped by it. We may glory in it. We can’t ignore it.

Richard Blake, “Interview with Richard Blake, 7th March 2014”, 2014-03-07.

October 20, 2016

QotD: The value of historical novels

October 19, 2016

World of Warships – Her Majesty’s Ships

Published on 18 Oct 2016

So I’m about to do an HMS Belfast video when Wargaming contact me and say “Hey, we gave you all the RN Light Cruisers again, your video can go up tomorrow and the whole thing goes live in two days. Any questions?”

TWO DAYS! YOU’RE KILLING ME HERE!

Yeah, I know, first world problems. Here’s the Royal Navy light cruiser line in general, and the premium tier 7 cruiser HMS Belfast in particular. THEY’RE AWESOME!

The Naval Hymn performed by the US Navy Band Chanters

Economics Made the World Great – and Can Make It Even Better

Published on Sep 23, 2016

A lot of doom and gloom types say we’re living in dark times. But they’re wrong.

While there are real problems, the world has never been healthier, wealthier, and happier than it is today. Over a billion people have been lifted from dire poverty in just the past few decades.

What has contributed to this improvement of our well-being? The answer can be found in the evolution of economic and policy ideas.

But we can still do better. How will we solve today’s challenges and what breakthroughs will spark change tomorrow?

QotD: Presence

She sat silently in her rocking chair. Some people are good at talking, but Granny Weatherwax was good at silence. She could sit so quiet and still that she faded. You forgot she was there. The room became empty. Tiffany thought of it as the I’m-not-here spell, if it was a spell. She reasoned that everyone had something inside them that told the world they were there. That was why you could often sense when someone was behind you, even if they were making no sound at all. You were receiving their I-am-here signal.

Some people had a very strong one. They were the people who got served first in shops. Granny Weatherwax had an I-am-here signal that bounced off the mountains when she wanted it to; when she walked into a forest, all the wolves and bears ran out the other side. She could turn it off, too. She was doing that now. Tiffany was having to concentrate to see her. Most of her mind was telling her that there was no one there at all.

Terry Pratchett, Wintersmith, 2006.

October 18, 2016

Mimi, Toutou and Fifi – The Utterly Bizarre Battle for Lake Tanganyika I THE GREAT WAR Special

Published on 17 Oct 2016

Check out http://audible.com/thegreatwar for a free trial and a free audiobook from the great selection that Audible has to offer.

This episodes contains images that are orphaned works for which the copyright holder is not known.

The Battle for Lake Tanganyika in German East Africa was one of the most bizarre battles of World War 1. It only really started once the Royal Navy had carried two boats through the jungle and the mountains from Capetown. Their names: Mimi and Toutou. Their commander: Geoffrey Spicer-Simson, probably the weirdest high ranking officer in the entire war.

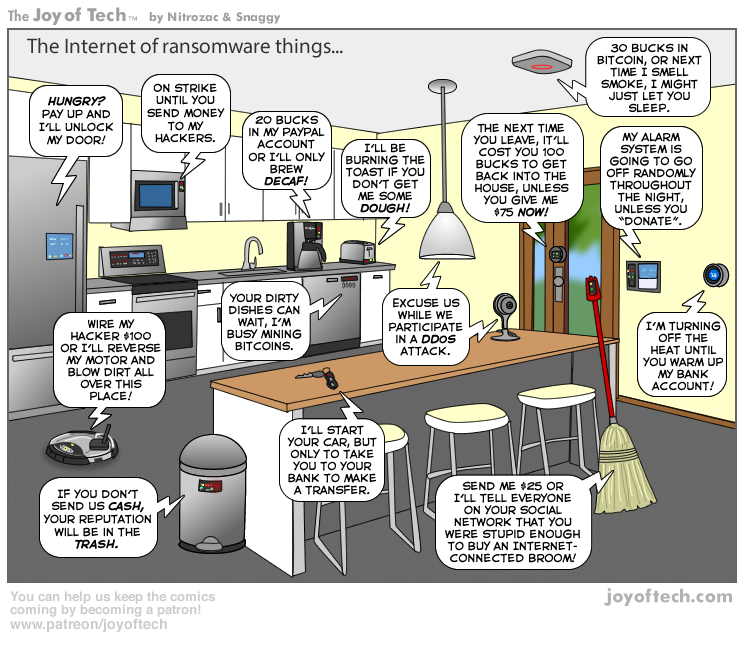

This is really what the Internet of Things will be like

QotD: “Smart Growth” regulations hurt the poor

In the 1970s, municipalities enacted new rules that were designed to protect farmland and to preserve green space surrounding rapidly growing cities by forbidding private development in those areas. By the late 1990s, this practice evolved into a land-use strategy called “smart growth.” (Here’s a video I did about smart growth.) While some of these initiatives may have preserved green space that can be seen, what is harder to see is the resulting supply restriction and higher cost of housing.

Again, the lower the supply of housing, other things equal, the higher real-estate prices will be. Those who now can’t afford to buy will often rent smaller apartments in less-desirable areas, which typically have less influence on the political process. Locally elected officials tend to be more responsive to the interests of current residents who own property, vote, and pay taxes, and less responsive to renters, who are more likely to be transients and nonvoters. That, in turn, makes it easier to implement policies that use regulation to discriminate against people living on low incomes.

Sandy Ikeda, “Shut Out: How Land-Use Regulations Hurt the Poor”, The Freeman, 2015-02-05.

October 17, 2016

Hillary Clinton tells us to expect a major US recession shortly after January 20, 2017

Fortunately, as Tim Worstall explains, politicians can rarely be believed — especially when it comes to economics:

Hillary Clinton Vows To Slam The Economy Into Recession Immediately Upon Election

This probably isn’t quite what Hillary Clinton intended to say but it is what she did say at a fundraiser on Friday night. That immediately upon election she would slam the US economy into a recession. For what she has said is that she’s not going to add a penny to the national debt. Which, in an economy running a $500 billion and change budget deficit means tax rises and or spending cuts of $500 billion and change immediately she takes the oath. And that’s a large enough and fierce enough change, before she does anything else, to bring back a recession.

[…]

Now, what she meant is something more like this. That she has some spending plans, which she does. And she is also proposing some tax rises. And that her tax rises will balance her spending plans and thus the mixture of plans will not increase the national debt. Which is possibly even true although I don’t believe a word of it myself. For her taxation plans are based upon static analyses when we really must use dynamic ones to measure tax changes. This is normally thought of as something that the right prefers. For if we measure the effects of tax cuts using the dynamic method then there will be some (please note, some, not enough for the cuts to pay for themselves) Laffer Effects meaning that the revenue loss is smaller than that under a static analysis. But this is also true about tax rises. Behaviour really does change when incentives change. Thus tax rises gain less revenue in real life than what a straight line or static analysis predicts.

That is, as I say, probably what she means. But that’s not actually what she said. She said she’ll not add a penny to the national debt. Which means that immediately on taking office she’s got to either raise taxes by $500 billion and change or reduce spending by that amount. Because the budget deficit is that $500 Big Ones and change at present and the deficit is the amount being added to the national debt each year. The problem with this being that that’s also some 3.5% or so of GDP and an immediate fiscal tightening of that amount would put the US economy back into recession.

Islam in Britain

At Samizdata, a look at a new book covering the Islamic communities of Britain:

In the book Medina in Birmingham, Najaf in Brent: Inside British Islam, the author – a BBC radio producer (boo, hiss) – attempts to provide an overview of the various strands of Islam in the UK. Her aim is not to tell us what to think but simply to provide the facts – what are they called? how many of them are there? where so they come from? what do they believe? etc. It is up to us, the readers, to draw conclusions.

Along the way there are a number of surprises. One of them is how different Islam is from Christianity. You would expect them to be rather similar given that they are both book-based, mono-theistic religions that revere both Abraham and Christ. Not a bit of it.

For example, in Christianity there is usually a close relationship between denomination and building. In Islam (at least in the UK) it is far more vague. A sect might be said to be “in control” of a mosque, the implication being that that control is temporary and could be lost. Many influential Muslim organisations such as Tablighi Jamaat and Jamaat-e-Islami have no mosques at all or very few.

Another is that the largest two sects in the UK are the Deobandis and Barelwis. No, I’d never heard of them either. For the record they are both Sunni (one definitely Sufi the other arguably so) and both originated in British India. It is worth pointing out that for the most part Bowen focuses on Sunni Islam but that is hardly surprising given that Sunnis vastly outnumber Shi’ites both globally and in the UK.

Another is that interest in Islam seems to be a second-generation thing. The first generation brought their Islam with them but seem to have regarded it as something they did rather than thought about. The second generation are much more inclined to read the Koran, take it seriously and ask questions. Even so, the most influential Islamic thinkers still tend to be based abroad.

I said earlier that it is left up to the reader to draw his own conclusions. So what does this reader conclude? Well, my biggest takeaway was that despite there being many strands of Islam and many weird and wonderful doctrinal disputes within Islam, there is no “good” Islam. The best you get is “less awful” Islam.

The History of Paper Money – I: Origins of Exchange – Extra History

Published on 1 Oct 2016

Giant stones sunk under the sea? Cows? Cowrie Shells? What do they all have in common? They were all money. Find out how we got from exchanging these things to doing 8 hours of work for a stack of paper that takes 2 seconds to print on The History of Paper Money.

QotD: The “narrative”

The most exhausting thing about our politics these days — other than the never-ending presidential election itself — is the obsession with “shaping the narrative.” By that I mean the effort to connect the dots between a selective number of facts and statistics to support one storyline about the state of the union.

Narrative-building is essential for almost every complicated argument because it’s the only way to get our pattern-seeking brains to discount contradictory facts and data. Trial lawyers understand this implicitly. Get the jury to buy the story, and they’ll do the heavy lifting of arranging the facts in just the right way.

[…]

I’m not naive. Crafting stories to serve political purposes is as old as politics itself. But the problem seems to be getting worse. Perhaps it’s because our country is so polarized and our media environment so balkanized and instantaneous. Politicians and journalists alike feel compelled to make facts serve some larger tale in every utterance. The reality is that life is complicated and every well-crafted narrative leaves out important facts.

Jonah Goldberg, “Narrative-Building Has Become a Political Obsession”, National Review, 2016-09-28.

October 16, 2016

Trump supporters aren’t who you think they are

An interesting article in, of all places, the Guardian discusses where Trump support comes from and why the media has difficulty identifying or covering them in a realistic fashion:

Hard numbers complicate, if not roundly dismiss, the oft-regurgitated theory that income or education levels predict Trump support, or that working-class whites support him disproportionately. Last month, results of 87,000 interviews conducted by Gallup showed that those who liked Trump were under no more economic distress or immigration-related anxiety than those who opposed him.

According to the study, his supporters didn’t have lower incomes or higher unemployment levels than other Americans. Income data misses a lot; those with healthy earnings might also have negative wealth or downward mobility. But respondents overall weren’t clinging to jobs perceived to be endangered. “Surprisingly”, a Gallup researcher wrote, “there appears to be no link whatsoever between exposure to trade competition and support for nationalist policies in America, as embodied by the Trump campaign.”

Earlier this year, primary exit polls revealed that Trump voters were, in fact, more affluent than most Americans, with a median household income of $72,000 – higher than that of Hillary Clinton or Bernie Sanders supporters. Forty-four percent of them had college degrees, well above the national average of 33% among whites or 29% overall. In January, political scientist Matthew MacWilliams reported findings that a penchant for authoritarianism – not income, education, gender, age or race –predicted Trump support.

These facts haven’t stopped pundits and journalists from pushing story after story about the white working class’s giddy embrace of a bloviating demagogue.

In seeking to explain Trump’s appeal, proportionate media coverage would require more stories about the racism and misogyny among white Trump supporters in tony suburbs. Or, if we’re examining economically driven bitterness among the working class, stories about the Democratic lawmakers who in recent decades ended welfare as we knew it, hopped in the sack with Wall Street and forgot American labor in their global trade agreements.

But, for national media outlets comprised largely of middle- and upper-class liberals, that would mean looking their own class in the face.

The faces journalists do train the cameras on – hateful ones screaming sexist vitriol next to Confederate flags – must receive coverage but do not speak for the communities I know well. That the media industry ignored my home for so long left a vacuum of understanding in which the first glimpse of an economically downtrodden white is presumed to represent the whole.

H/T to John Donovan who comments “I’m pretty sure I don’t share this Kansan’s policy preferences, but I find her view here refreshing.”

Soldiers With Glasses – Industrial Centres – Frontline Generals I OUT OF THE TRENCHES

Published on 15 Oct 2016

Indy is answering your questions about the First World War again. This time we talk about:

– soldiers wearing glasses

– the different industrial centres of the major nations

– generals leading from the frontline and from the rear

QotD: Epicurean physics

It would be easy to diverge from this general overview into a detailed examination of the physics. This is because Epicurus seems to have been largely right. We now believe, as he did, that the universe is made of atoms, and if we do not now talk about motion, we do talk about energy and force. His physics are an astonishing achievement.

Of course, he was often wrong. He denigrated mathematics. He seems to have believed that the sun and moon were about the same size as they appear to us. Then there is an apparent defect in his conception of the atomic movements. Does the universe exist by accident? Or are their laws of nature beyond the existence and movement of the atoms? The first is not impossible. An infinite number of atoms in an infinite void over infinite time will, every so often, come together in an apparently stable universe. They may also hold together, moving in clusters in ways that suggest regularity. But this chance combination might be dissolved at any moment — though, given every sort of infinity, some of these universes will continue for long periods.

If Epicurus had this first in view, what point in trying to explain present phenomena in terms of cause and effect? Causality only makes sense on the assumption that the future will be like the past. If he had the second in mind, it is worth asking what he thought to he nature of these laws? Might they not, for example, have had an Author? Since Newton, we have contented ourselves with trying to uncover regularities of motion and not going beyond these. But the Greeks had a much stronger teleological sense.

Perhaps these matters were not discussed. Perhaps they were discussed, but we have no record of them in the surviving discussions. Or perhaps they have survived, but I have overlooked them. But it does seem to me that Epicurean physics do not fully discuss the nature of the laws that they assume.

On the other hand, let me quote two passages from his surviving writings:

Moreover, there is an infinite number of worlds, some like this world, others unlike it. For the atoms being infinite in number… are borne ever further in their course. For the atoms out of which a world might arise, or by which a world might arise, or by which a world might be formed, have not all be expended on one world or a finite number of worlds, whether like or unlike this one. Hence there will be nothing to hinder and infinity of worlds….

And further, we must not suppose that the worlds have necessarily one and the same shape. For nobody can prove that in one sort of world there might not be contained, whereas in another sort of world there could not possibly be, the seeds out of which animals and plants arise and the rest of the things we see.

What we have here is the admission that there may, in the infinite universe, be other worlds like our own, and these may contain sentient beings like ourselves. And there may be worlds inconceivably unlike our own. And there is the claim that living beings arise and develop according to natural laws. Epicurus would not have been surprised either by modern physics or by Darwinism. […]

However, while the similarities between Epicurean physics and modern science are striking, there is one profound difference. For us, the purpose of science is to give us an understanding of the world that brings with it the ability to control the world and remake it for our own convenience. This is our desire, and this has been our achievement because we have fully developed methods of observation and experiment. The Greeks had limited means of observation — no microscopes or telescopes, nor even accurate clocks. Nor had they much conception of experiment.

Moreover, scientific progress was neither conceived by Epicurus nor regarded as desirable. He says very emphatically:

If we had never been troubled by celestial and atmospheric phenomena, nor by fears about death, nor by our ignorance of the limits of pains and desires, we should have had no need of natural science.

He says again:

…[R]emember that, like everything else, knowledge of celestial phenomena, whether taken along with other things or in isolation, has no other end in view than peace of mind and firm convictions.

Sean Gabb, “Epicurus: Father of the Englightenment”, speaking to the 6/20 Club in London, 2007-09-06.

October 15, 2016

Unilever attempts to “draw the longbow” over Marmite

Marmite, an almost uniquely British product, is in the headlines this week over an attempt by manufacturer Unilever to jack up prices due to the drop in the pound against the Euro. As Tim Worstall points out, this is not in any way justified because all of the inputs to the product are produced in the UK (that is, the input prices have not significantly changed regardless of how the pound is doing in terms of the Euro exchange rate):

Personally I love the stuff but even in Britain that puts me in a distinct minority.

The other amusement though comes from the action itself. For what Unilever is doing here is what we in Britain refer to, colloquially, as “taking the piss.”

Yesterday, the implications of the pound’s fall on prices and retailer margins hit home for the wider public as the country’s leading supermarket engaged in a war over prices with its highest-profile supplier of branded goods.

Either UK consumers will eat store-branded yeast extract, or they’ll pay more for Marmite, or the impact of the pound’s fall will be shared between supplier and retailer.

This is superficially plausible. Britain imports some 40% of its food and as a result of the Brexit vote the pound has fallen against other currencies. We would therefore expect to see some price rises in food items. Obviously in those imported that have to be paid for in that more expensive foreign funny money. But also in certain domestic foods which substitute for those foreign ones. So, for example, if foreign chicken rises in price then so too will British chicken as demand for it rises–people will substitute away from the more expensive foreign muck to the purer and more delightful domestic production.

However, this really doesn’t hold for Marmite.

Consumer goods giant Unilever has been accused of ‘exploiting’ British shoppers by withdrawing more than 200 much-loved products from Tesco after the supermarket refused to agree to its 10 per cent price hike. Critics claim the world’s largest consumer goods manufacturer, which makes an estimated £2billion profit a year, is ‘using Brexit as an excuse to raise prices’. The Anglo-Dutch firm, which heavily campaigned against Brexit, claims it has been forced to increase prices as a result of the falling value of the pound in the wake of the referendum.

The reason it doesn’t hold for Marmite is because it is not imported and nor are any close substitutes in any volume. Thus Unilever’s costs have not gone up in any manner at all over this. Quite the contrary in fact, the only flow, other than trivial amounts of Vegemite an Australian version of a similar thing, is of Marmite out of the UK. Meaning that Unilever’s profits on Marmite exports have risen as a result of the pound’s fall. Their costs, revenues and margins in sterling are exactly what they were for domestic sales before that slump in the pound.

The row is said to have developed when Unilever – which says it faces higher costs because of the fall in sterling – attempted to increase wholesale prices.

It’s simply not true thus the micturation extraction.