Pio Moa’s thesis is that the Spanish Civil War was not a usurping revolt against a functioning government, but a belated attempt to restore order to a country that had already collapsed into violent chaos five years before the Fascists landed in 1936.

I’ve studied the history of the Spanish Civil War enough to know that Moa’s contrarian interpretation is not obviously crazy. I had an unusual angle; I’m an anarchist, and wanted to grasp the ideas and role of the Spanish anarchist communes. My conclusions were not pleasant. In short, there were no good guys in the Spanish Civil War.

First, the non-anarchist Left in Spain really was pretty completely Stalin’s creature. The volunteers of the International Brigade were (in Lenin’s timeless phrase) useful idiots, an exact analogue of the foreign Arabs who fought on in Baghdad after Iraqi resistance collapsed (and were despised for it by the Iraqis). They deserve neither our pity nor our respect. Insofar as Moa’s thesis is that most scholarship about the war is severely distorted by a desire to make heroes out of these idiots, he is correct.

Second, the Spanish anarchists were by and large an exceedingly nasty bunch, all resentment and nihilism with no idea how to rebuild after destroying. Wiping them out (via his Communist proxies) may have been one of Stalin’s few good deeds.

Third, the Fascists were a pretty nasty bunch too. But, on the whole, probably not as nasty as their opponents. Perceptions of them tend to be distorted by the casual equation of Fascist with Nazi — but this is not appropriate. Spanish Fascism was unlike Communism or Italian and German Fascism in that it was genuinely a conservative movement, rather than a attempt to reinvent society in the image of a revolutionary doctrine about the perfected State.

Historians and political scientists use the terms “fascist” and “fascism” quite precisely, for a group of political movements that were active between about 1890 and about 1975. The original and prototypical example was Italian fascism, the best-known and most virulent strain was Naziism, and the longest-lasting was the Spanish nationalist fascism of Francisco Franco. The militarist nationalism of Japan is often also described as “fascist” .

The shared label reflects the fact that these four ideologies influenced each other; Naziism began as a German imitation of Italian fascism, only to remake Italian (and to some extent Spanish) fascism in its own image during WWII. The militarist Japanese fascists took their cues from European fascists as well as an indigenous tradition of absolutism with very similar structural and psychological features

The shared label also reflects substantially similar theories of political economics, power, governance, and national purpose. Also similar histories and symbolisms. Here are some of the commonalities especially relevant to the all too common abuse of the term.

Fascist political economics is a corrupt form of Leninist socialism. In fascist theory (as in Communism) the State owns all; in practice, fascists are willing to co-opt and use big capitalists rather than immediately killing them.

Fascism mythologizes the professional military, but never trusts it. (And rightly so; consider the Von Stauffenberg plot…) One of the signatures of the fascist state is the formation of elite units (the SA and SS in Germany, the Guardia Civil in Spain, the Republican Guard and Fedayeen in Iraq) loyal to the fascist party and outside the military chain of command.

Fascism is not (as the example of Franco’s Spain shows) necessarily aggressive or expansionist per se. In all but one case, fascist wars were triggered not by ideologically-motivated aggression but by revanchist nationalism (that is, the nation’s claims on areas lost to the victors of previous wars, or inhabited by members of the nationality agitating for annexation). No, the one exception was not Nazi Germany; it was Japan (the rape of Manchuria). The Nazi wars of aggression and Hussein’s grab at Kuwait were both revanchist in origin.

Fascism is generally born by revolution out of the collapse of monarchism. Fascism’s theory of power is organized around the ‘Fuehrerprinzip‘, the absolute leader regarded as the incarnation of the national will.

But…and this is a big but…there were important difference between revolutionary Fascism (the Italo/German/Baathist variety) and the more reactionary sort native to Spain and Japan.

Eric S. Raymond, “Fascism is not dead”, Armed and Dangerous, 2003-04-22.

August 7, 2016

QotD: “… there were no good guys in the Spanish Civil War”

August 6, 2016

QotD: The sunk cost theory of relationships

“Seriously?” you’re asking. “Love is like … automobile manufacturing?” Well, no. But companies are composed of people. And people tend to make the same sort of mistakes over and over. This particular mistake is so common that economists have a name for it: the sunk cost fallacy.

A sunk cost is, well, like a sunken ship: It’s gone, and you cannot retrieve it, or you can only retrieve it at immense expense. The correct and rational way to deal with a sunk cost is to ignore it — to make decisions without thinking about the money or time you’ve already invested.

Think of it this way: If you’re horribly ill and you’ve spent a bunch of money on tickets to a show, there’s no point thinking about how much the tickets cost, because no matter what you do, you can’t get it back. What you should be thinking about is whether you will enjoy the show in your current condition. Making yourself miserable will not somehow rescue the money; it just layers another cost — the agonizing hours you will spend wishing that you were home in bed — on top of the cash you used to buy the tickets.

Unfortunately, human beings are terrible at thinking this way. Once we have lost something, we become desperate to get it back. The sunk cost fallacy appears over and over in all facets of human life: Think of companies that spend vast fortunes trying to salvage doomed IT products, or compulsive gamblers who go back again and again trying to get even with the house, a feat that is mathematically nearly impossible over the long run. Even if we’ve never darkened the door of a casino, when we are dealing with sunk costs, all of us easily turn into wild gamblers, ready to take ultra-long shots rather than admit the loss and move on.

And boy, does it show up in relationships. I cannot count the number of women I have watched throw year after year into a doomed relationship because they are desperate to redeem the prime dating years they have already wasted on a man who does not want to share his future with them. Every one of them said afterward that she wished she’d cut things off when it became clear that he wasn’t as enthusiastic as she was.

Megan McArdle, “Happy Valentine’s Day! Now Cut Your Losses”, Bloomberg View, 2015-02-13.

August 5, 2016

Germany’s Grandeur – Analyzing the War Effort I THE GREAT WAR Week 106

Published on 4 Aug 2016

It has been two years since the global escalation that lead to World War 1. Three of the biggest battles in history are fought simultaneously now and there is no end in sight. When asked about the state of the war, the nations are still determined but the German position is still full of grandiose exaggerations.

QotD: Slavery as an American invention

I started giving quizzes to my juniors and seniors. I gave them a ten-question American history test… just to see where they are. The vast majority of my students – I’m talking nine out of ten, in every single class, for seven consecutive years – they have no idea that slavery existed anywhere in the world before the United States. Moses, Pharaoh, they know none of it. They’re 100% convinced that slavery is a uniquely American invention… How do you give an adequate view of history and culture to kids when that’s what they think of their own country – that America invented slavery? That’s all they know.

Dr. Duke Pesta, in conversation with Stefan Molyneux, transcribed by David Thompson, 2016-07-27.

August 4, 2016

Cargo shorts are now a fashion crime

In the Wall Street Journal, Nicole Hong explains why people like me need to be shunned and shamed for our favourite summer shorts:

Relationships around the country are being tested by cargo shorts, loosely cut shorts with large pockets sewn onto the sides. Men who love them say they’re comfortable and practical for summer. Detractors say they’ve been out of style for years, deriding them as bulky, uncool and just flat-out ugly.

Mr. Hansen’s wife, Ashleigh Hansen, said she sneaks her husband’s cargo shorts off to Goodwill when he’s not around. Mrs. Hansen, 30, no longer throws them out at home because her husband has found them in the trash and fished them out.

“I despise them,” she said. “There were so many good things about the ’90s. Cargo shorts were not one of them.”

Fashion historians believe cargo pants were introduced around the 1940s for military use. In the U.S. Air Force, narrow cockpits meant pilots needed pockets in the front of their uniforms to access supplies during flight. British soldiers climbing or hiding in high places found pockets on cargo pants more effective than utility belts for storing ammunition.

[…]

“It’s a reflection on me, like ‘How did she let him out the door like that?’ ” she said.

[…]

Tom Lommel, a 46-year-old actor in Los Angeles, said he loves wearing cargo shorts because they’re like “socially acceptable sweatpants,” referring to their lightweight nature. He says they’re more breathable than tight Bermuda shorts.

His wife, however, isn’t a fan. Mr. Lommel, who often works from home, seizes opportunities when his wife is away at work to wear his cargo shorts.

“Every time I put them on, I am conscious of the fact that I am now being disobedient in my marriage,” he said.

Mr. Lommel’s wife, Lyndsay Peters, disputes the idea that he tries to wear cargo shorts only when she’s not around. “I wish that were the truth,” she said. “If he was only wearing them when I could not look at him, that would be perfect.”

QotD: The invention of liberty

I believe that liberty is the only genuinely valuable thing that men have invented, at least in the field of government, in a thousand years. I believe that it is better to be free than to be not free, even when the former is dangerous and the latter safe. I believe that the finest qualities of man can flourish only in free air – that progress made under the shadow of the policeman’s club is false progress, and of no permanent value. I believe that any man who takes the liberty of another into his keeping is bound to become a tyrant, and that any man who yields up his liberty, in however slight the measure, is bound to become a slave.

H.L. Mencken, “Why Liberty?”, Chicago Tribune, 1927-01-30.

August 3, 2016

The scandal of the Chevalier d’Eon

In Atlas Obscura, Linda Rodriguez McRobbie tells the story of the French soldier, diplomat and spy, the Chevalier d’Eon (also known as Mademoiselle la Chevaliere d’Eon):

Mademoiselle de Beaumont or The Chevalier D’Eon. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-DIG-ds-03347)

When the Chevalier d’Eon left France in 1762, it was as a diplomat, a spy in the French king’s service, a Dragoon captain, and a man. When he returned in July 1777, at the age of 49, it was as a celebrity, a writer, an intellectual, and a woman — according to a declaration by the government of France.

What happened? And why?

The answer to those questions is complex, obscured by layers of bad biography, speculation and rumor, and shifting gender and psychological politics in the years since, as well as d’Eon’s own attempts to reframe his story in a way that would make sense to his contemporary society. (Note: In consultation with d’Eon’s biographer, I have decided to use the male pronoun when talking about d’Eon before the gender shift and the female pronoun after.) Professor Gary Kates of Pomona College is one of the first modern academics to look closely at the life — or lives — of the Chevalier d’Eon, in his comprehensive biography Monsieur d’Eon Is a Woman. Kates had access to d’Eon’s personal papers, a treasure trove of manuscripts, diaries, financial records, documents, and letters housed at the University of Leeds, and his work is widely considered the best place to start when considering d’Eon.

The story Kates tells is a complex narrative, involving Ancien Regime intrigue, secret spy rings, political necessity, burgeoning celebrity culture, and nascent feminism. The meaning of d’Eon’s transformation has been dissected for centuries; feminist writer Mary Wollstonecraft praised d’Eon in their lifetime and contemporary trans groups have named themselves in d’Eon’s honor.

Even so, Kates cautions that the history of this fascinating figure is far from complete. “I don’t think I’ve written the definitive book on d’Eon,” he says. How could he? This is a person who lived enough for three lifetimes.

QotD: The lure of “new” old art

What is it about stories like these [the discovery of “lost” artistic masterworks] that we find so unfailingly seductive? No doubt the Antiques Roadshow mentality is part of it. All of us love to suppose that the dusty canvas that Aunt Tillie left to us in her will is in fact an old master whose sale will make us rich beyond the dreams of avarice. And I’m sure that the fast-growing doubts surrounding Go Set a Watchman (which were well summarized in a Feb. 16 Washington Post story bearing the biting title of “To Shill a Mockingbird”) have pumped up its news value considerably.

But I smell something else in play. I suspect that for all its seeming popularity — as measured by such indexes as museum attendance — there is a continuing and pervasive unease with modern art among the public at large, a sinking feeling that no matter how much time they spend looking, reading or listening, they’ll never quite get the hang of it. As a result, they feel a powerful longing for “new” work by artists of the past.

To be sure, most ordinary folks like at least some modern art, but they gravitate more willingly to traditional fare. Just as “Our Town” (whose form, lest we forget, was ultramodern in 1938) is more popular than “Waiting for Godot,” so, too, are virtually all of our successful “modern” novels essentially traditional in style and subject matter. In some fields, domestic architecture in particular, midcentury modernism is still a source of widespread disquiet, while in others, like classical music and dance, the average audience member does little more than tolerate it.

Terry Teachout, “The lure of ‘new’ old art”, About Last Night, 2015-02-27.

August 2, 2016

The Great Explorer – Ernest Shackleton I WHO DID WHAT IN WW1?

Published on 1 Aug 2016

Ernest Shackelton set sail for the Antarctic when most young men in Europe were setting sail to fight a war. While millions of them died, he was completely isolated trying to survive the harsh conditions. Shackelton’s expediton was probably one of the last grand ventures from the age of wonder and when he reached civilisation again, the world had truly gone mad.

The Old Third Vineyards wins their appeal against the VQA

The Ontario government granted the Vintner’s Quality Alliance (VQA) some regulatory power to police the marketing and labelling of wines made in Ontario, including (the VQA thought) the rights to restrict the use of certain geographical designators like “Ontario” and “Prince Edward County” to VQA-compliant wineries. In a recent decision, a non-VQA winery located in Prince Edward County won an appeal against the VQA’s over-restrictive order:

Yesterday (July 28, 2016) was a big day for The Old Third Vineyards, a small, boutique winery located in Prince Edward County. The Licence Appeal Tribunal ruled in their favour against the Vintner’s Quality Alliance Ontario (VQAO) compliance order that they remove “Prince Edward County” from The Old Third website.

The Old Third Vineyard is located in Prince Edward County. It is owned and operated by winemaker Bruno François and Jens Korberg. They make Pinot Noir and Cabernet Franc wines, sold from their estates. Their wines have received ratings of 90 points or higher by esteemed wine experts Jamie Goode, John Szabo and Quench’s own Rick VanSickle. Each vintage – only one per year per variety – is bottled with a wine label that reads “Product of Canada”.

However, their website has a heading tagline that reads “Producers of fine wine and cider in Prince Edward County.” This is an issue for the VQA.

On February 3, 2016, VQA compliance officer Susan Piovesan emailed The Old Third with regards to the use of the geographic designation “Prince Edward County” on their website.

In other words, the VQA wanted to prevent the Old Third Vineyards from even revealing where in the country they were located because the legal designator for that area is also a restricted term for use by the VQA’s own wineries on wine bottle labels. Old Third wasn’t using it on a label, but as any common sense interpretation would agree, they have to indicate where customers can find them if they want to sell much of their wine … and they’re physically located in Prince Edward County, and said that on their website.

The VQA argued that The Old Third are trying to monopolize on the value the VQA has added to the term “Prince Edward County” by making it an official wine designation. The Tribunal disagreed: “The information conveyed in the banner … locates it geographically. Giving the words, in context, their ordinary meaning, they do not convey that the Appellant produces a Prince Edward County wine.”

The Tribunal’s ruling in favour of The Old Third shows that, even if an organization that regulates wine believes they own a term or regional name, it doesn’t mean they have the right to enforce their designations on those wineries that don’t wish to buy into the designation. The Old Third is a small vineyard in Prince Edward County and it will most likely remain that way.

And it’s these small wineries that first put Prince Edward County on the wine scene – there wouldn’t be a VQA designation for Prince Edward County if it weren’t for the wineries and estates that were producing quality wines long before the VQA came around in 2007: Waupoos Winery, The Grange of Prince Edward Vineyards and Winery, Casa-Dea Estates Winery, By Chadsey’s Cairns Winery, Sandbanks Estates Winery… the list goes on (and on).

QotD: The deadweight costs of different forms of taxation

All taxes have something called a “deadweight cost”. This is simply economic activity that doesn’t happen because of the simple fact that we’re levying a tax. If we tax the purchase of apples then fewer apples will be purchased. This is entirely divorced, by the way, from any good that might be achieved by how we spend that revenue collected. We also know that different taxes have different deadweight costs. We even have a ranking of them. At the top, with the highest costs for the revenue collected, we’ve transactions taxes like the financial transactions tax under consideration. This is so expensive that it’s a really, really, bad idea to tax in this manner. Then come capital and corporate taxes, then with lower again deadweights incomes taxes, then consumption and then finally repeated taxes on real property, or land value taxation. If we were interested only in efficiency (we’re not, equity is important too) then we would collect as much as we could from a land value tax, then from Pigou and sin taxes (carbon emissions, cigarettes, booze) then general consumption taxes and so on. Perhaps leaving corporates and capital entirely untaxed. And there’s a whole field of study, optimal taxation theory, that suggests that we really should do that and the general prescription is the progressive consumption tax. There’s general agreement that on purely those efficiency grounds this is about the best we can do with a tax system.

Tim Worstall, “Surprisingly Perhaps, State Republicans Are Actually Correct On The Economics Of This”, Forbes, 2015-02-14.

August 1, 2016

Top 10 Misconceptions About World War 1 I THE GREAT WAR Special

Published on 31 Jul 2016

We thought about a list of misconceptions about World War 1 that don’t want to die even 100 years later.

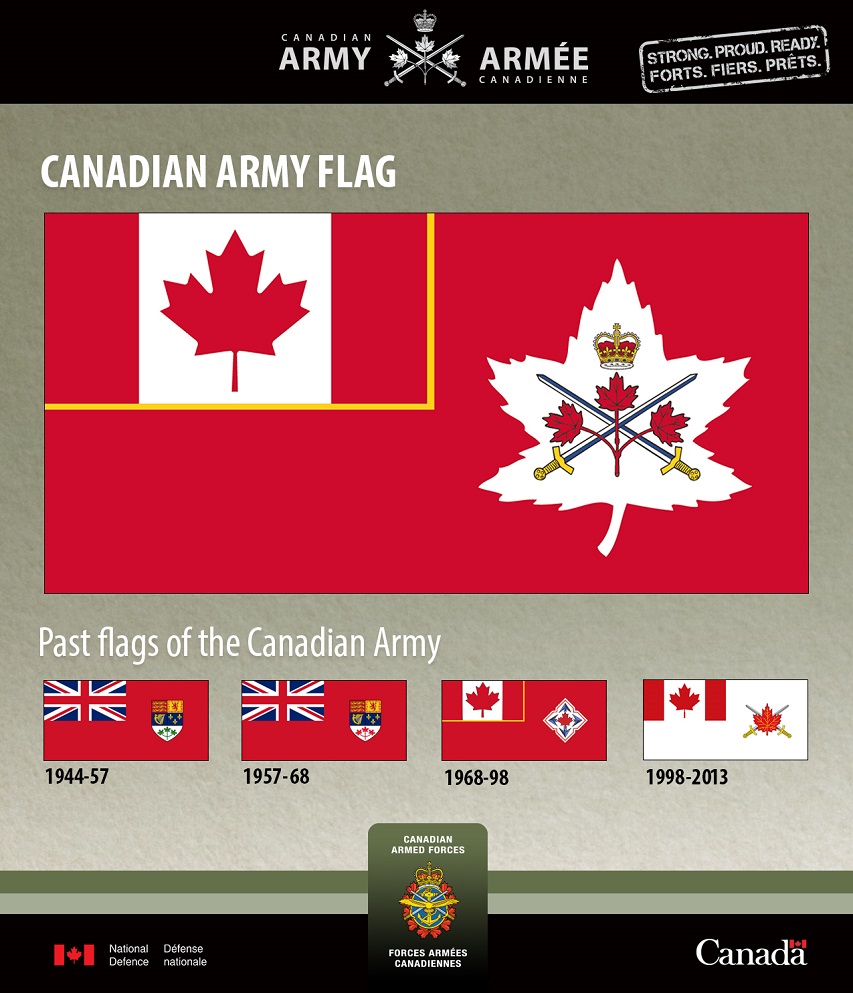

A new flag for the Canadian Army

Chris Banks posted a link to this article in the Lorne Scots Facebook group:

The Canadian Army (CA) will advance into the future under a new flag that nods to its proud past.

The flag was unveiled July 14, 2016, during a ceremony on Parliament Hill in which CA members welcomed their new Commander, Lieutenant-General Paul Wynnyk.

The new design features the Canadian flag and a white, stylized maple leaf against a red background. Superimposed on the white maple leaf is the badge that members used during the Second World War and the Korean conflict, consisting of three maple leaves over a pair of crossed swords. Sitting atop the centre leaf is an image of St. Edward’s Crown, a symbol that has been used in coronation ceremonies for over 300 years.

The maple leaf was worn on the collars of Canadian soldiers who fought in the Battle of Vimy Ridge during the First World War, and was included on the new flag to honour the 100th anniversary of the battle, which will be marked in 2017. The same maple leaf flew on the Headquarters flags of the fighting Divisions during the Second World War and still flies across Canada at the CA’s various Division Headquarters.

QotD: Heinlein versus Pournelle

I took some heat recently for describing some of Jerry Pournelle’s SF as “conservative/militarist power fantasies”. Pournelle uttered a rather sniffy comment about this on his blog; the only substance I could extract from it was that Pournelle thought his lifelong friend Robert Heinlein was caught between a developing libertarian philosophy and his patriotic instincts. I can hardly argue that point, since I completely agree with it; that tension is a central issue in almost everything Heinlein ever wrote.

The differences between Heinlein’s and Pournelle’s military SF are not trivial — they are both esthetically and morally important. More generally, the soldiers in military SF express a wide range of different theories about the relationship between soldier, society, and citizen. These theories reward some examination.

First, let’s consider representative examples: Jerry Pournelle’s novels of Falkenberg’s Legion, on the one hand, and Heinlein’s Starship Troopers on the other.

The difference between Heinlein and Pournelle starts with the fact that Pournelle could write about a cold-blooded mass murder of human beings by human beings, performed in the name of political order, approvingly — and did.

But the massacre was only possible because Falkenberg’s Legion and Heinlein’s Mobile Infantry have very different relationships with the society around them. Heinlein’s troops are integrated with the society in which they live. They study history and moral philosophy; they are citizen-soldiers. Johnnie Rico has doubts, hesitations, humanity. One can’t imagine giving him orders to open fire on a stadium-full of civilians as does Falkenberg.

Pournelle’s soldiers, on the other hand, have no society but their unit and no moral direction other than that of the men on horseback who lead them. Falkenberg is a perfect embodiment of military Führerprinzip, remote even from his own men, a creepy and opaque character who is not successfully humanized by an implausible romance near the end of the sequence. The Falkenberg books end with his men elevating an emperor, Prince Lysander who we are all supposed to trust because he is such a beau ideal. Two thousand years of hard-won lessons about the maintenance of liberty are thrown away like so much trash.

In fact, the underlying message here is pretty close to that of classical fascism. It, too, responds to social decay with a cult of the redeeming absolute leader. To be fair, the Falkenberg novels probably do not depict Pournelle’s idea of an ideal society, but they are hardly less damning if we consider them as a cautionary tale. “Straighten up, kids, or the hero-soldiers in Nemourlon are going to have to get medieval on your buttocks and install a Glorious Leader.” Pournelle’s values are revealed by the way that he repeatedly posits situations in which the truncheon of authority is the only solution. All tyrants plead necessity.

Eric S. Raymond, “The Charms and Terrors of Military SF”, Armed and Dangerous, 2002-11-13.