By way of Amy Alkon’s blog, here’s the Oberlin College Choir (motto: “Feelz before Realz”) responding to the Christina Hoff Sommers controversy at the college:

May 11, 2015

Nepal’s tragic unpreparedness for disaster

In The Walrus, Manjushree Thapa explains why Nepal was so badly prepared for the earthquake:

Following the April 25 earthquake, Nepalis have had to learn the value of preparedness in the most painful way possible. In the aftermath, Pushpa Acharya, a Nepali friend at the University of Toronto, observed, “Knowledge was not our problem.” Indeed. We all knew that our country sits on an active fault line, where the subcontinent collided with the Eurasian plate with such force it created the Himalayas. The last big quake took place in 1934. Others have since struck, but none with the force of 1934’s 8.0 or April 25’s 7.9. We knew that a big earthquake was due.

It was our duty to prepare, and though some of us did so individually, as a society we ignored the warnings. In the past ten days, during search and rescue, and then the beginnings of relief, we’ve had to do some hard thinking about how our country could become more responsible going forward. The root problem may seem obvious: Nepal is one of the poorest countries in the world. Its poverty is, however, a symptom of our history of ill governance, and the reason for our national failure to prepare, which has kept us from becoming a functioning democracy.

When the earthquake struck, the country was in a deep and deeply depressing stupor. The governing parties — a coalition of the Nepali Congress Party and the Unified Marxist Leninists — had reached an impasse with Nepal’s thirty-three opposition parties about what kind of constitution to draft. There was no plan for the country as a whole, let alone in the case of an emergency. The drafting of a constitution has preoccupied, confounded, and eluded Nepal’s polity since 2006, when the Maoists ended a ten-year insurgency to join forces with other parties to remove Gyanendra Bir Bikram Shah. Nepal’s king had used the war as an excuse to end a fragile fifteen-year spell of democracy and install his own military-backed rule. A mass movement restored democracy, and the subsequent peace process promised to restructure the country along just and equitable lines through the drafting of a new constitution

Who Pays the Tax?

Published on 27 Jan 2015

Who bears the burden of a tax? Buyers or sellers? Why is it that the more elastic side of the market pays a smaller share of a tax? Again, we’ll apply what we know to the example of Social Security taxes and also look at the health insurance mandate as a part of the Affordable Care Act. Who pays for the mandate? The employers or the workers? We’ll also look at supply and demand of labor. Is the demand for labor more elastic than the supply?

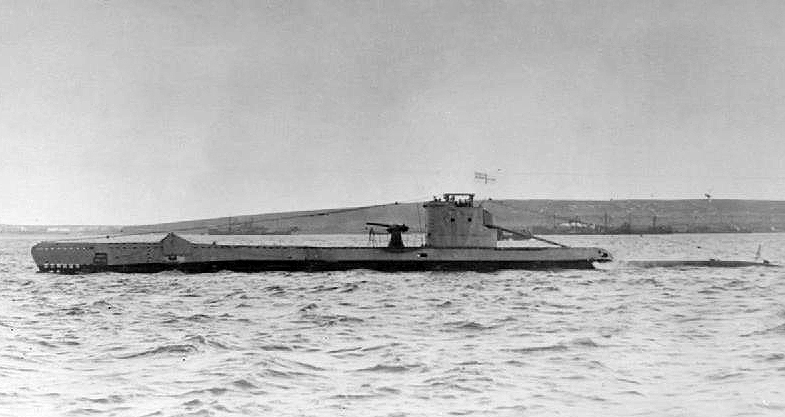

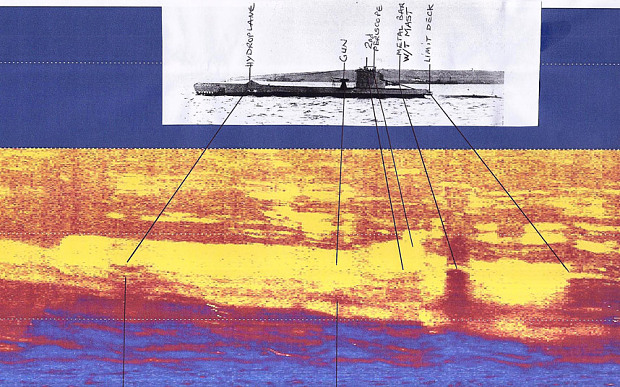

After 74 years, the remains of HMS Urge discovered off the Libyan coast

In The Telegraph a report on the discovery of a Royal Navy submarine wreck from 1942:

A Royal Navy submarine paid for by a town holding dances and whist drives is believed to have been discovered more than 70 years after it vanished during the Second World War.

The British submarine HMS Urge was paid for by the townspeople of Bridgend, South Wales, but sunk without trace in the Mediterranean in 1942.

It disappeared while making a voyage from the island of Malta to the Egyptian city of Alexandria – and families of the 29 crew and 10 passengers never knew what happened.

For more than 70 years, its resting place has remained a mystery. But a 76-year-old scuba diver claims he has discovered its wreck 160ft (50m) below the waves off the Libyan coast.

QotD: Tariffs are generally harmful, but persist anyway

For another example, consider trade barriers such as tariffs. There are good economic arguments to show that we would be better off if we went to complete free trade. That seems puzzling — if we would be, why don’t we?

The answer is provided by public choice theory, the branch of economics that deals with the workings of the political market. A tariff makes the inhabitants of the country that imposes it worse off but the politicians who pass the tariff better off, since it benefits a concentrated interest group at the cost of dispersed interest groups. More concentrated interest groups are better able to pay politicians to do things for them. Trade policy is optimized, but for the wrong objective.

David D. Friedman, “Why Improving Things Is Hard”, Ideas, 2014-07-08.