Published on 26 Jan 2015

Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, also known as the Lion of Africa, was commander of the German colonial troops in German East Africa during World War 1. His guerilla tactics used againd several world powers of the time are considered to be one of the most successful military missions of the whole war. In Germany, he was celebrated as a hero until recently. But recent historical research show a picture much more controversial than the one of a glorious hero.

January 28, 2015

Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck I WHO DID WHAT IN WW1?

Employment skills at the very basic level

Warren Meyer says what the US needs to do is to make changes to the structure of the working world to allow companies to profitably hire low-skilled workers:

A lot of head scratching goes on as to why, when the income premium is so high for gaining skills, there are not more people seeking to gain them. School systems are often blamed, which is fair in part (if I were to be given a second magic wand to wave, it would be to break up the senescent government school monopoly with some kind of school choice system). But a large portion of the population apparently does not take advantage of the educational opportunities that do exist. Why is that?

When one says “job skills,” people often think of things like programming machine tools or writing Java code. But for new or unskilled workers — the very workers we worry are trapped in poverty in our cities — even basic things we take for granted like showing up on-time reliably and working as a team with others represent skills that have to be learned. Amazon.com CEO Jeff Bezos, despite his Princeton education, still learned many of his first real-world job skills working at McDonald’s. In fact, back in the 1970’s, a survey found that 10% of Fortune 500 CEO’s had their first work experience at McDonald’s.

Part of what we call “the cycle of poverty” is due not just to a lack of skills, but to a lack of understanding of or appreciation for such skills that can cross generations. Children of parents with few skills or little education can go on to achieve great things — that is the American dream after all. But in most of these cases, kids who are successful have parents who were, if not educated, at least knowledgeable about the importance of education, reliability, and teamwork — understanding they often gained via what we call unskilled work. The experience gained from unskilled work is a bridge to future success, both in this generation and the next.

But this road to success breaks down without that initial unskilled job. Without a first, relatively simple job it is almost impossible to gain more sophisticated and lucrative work. And kids with parents who have little or no experience working are more likely to inherit their parent’s cynicism about the lack of opportunity than they are to get any push to do well in school, to work hard, or to learn to cooperate with others.

Unfortunately, there seem to be fewer and fewer opportunities for unskilled workers to find a job. As I mentioned earlier, economists scratch their heads and wonder why there are not more skilled workers despite high rewards for gaining such skills. I am not an economist, I am a business school grad. We don’t worry about explaining structural imbalances so much as look for the profitable opportunities they might present. So a question we business folks might ask instead is: If there are so many under-employed unskilled workers rattling around in the economy, why aren’t entrepreneurs crafting business models to exploit this fact?

The great and the good gather at Davos

And Monty calls ’em exactly what they are:

Luckily, all is not lost. Our moral and ethical betters have gathered in Davos to light their cigars with hundred-dollar bills while mocking the tubercular bootblack who’s been pressed into service to keep their shoes looking spiffy while they chat and laugh and eat lobster canapes. Oh, wait, I read that wrong, sorry. They’re in Davos to discuss the pressing problem of Global Warming(tm). Because they’re so concerned about Global Warming(tm) that they felt compelled to fly their private jets to an upscale enclave in the Swiss Alps to talk about it. While making fun of the tubercular bootblack who’s spit-shining their wingtips.

Don’t get me wrong – I’m a big believer in ostentatious displays of wealth. If I had the money, I’d build a hundred-foot-high statue of myself made out of pure platinum and then hire homeless people to worship at it for no fewer than eight hours per day. (I’d pay them a fair wage, though. What’s the going rate for abject obeisance to a living God? I’ll have to look it up.) But this Davos thing is just…rank. It’s a collection of rich fart-sniffers who want to congratulate each other on how socially conscious they are, and how much they care about the Little People. (Except the tubercular bootblack, whom they often kick with their rich-guy shoes.)

Spending more money on education won’t guarantee better outcomes for students

Not having gone to university myself, I can’t speak from direct personal experience, but my strong sense is that the university degree today fulfils almost exactly the role for job-seekers that a high school diploma did about a generation ago. Most of the “entry level” jobs that actually offer some sort of career progression require no more skill or preparation now than they did 25 or 30 years ago … but the combination of lowered standards in secondary school and the vast expansion of post-secondary education have encouraged employers to filter job applicants for such openings by education first. As a direct result, parents have been pushing their children toward university as the only way to ensure those kids have a fighting chance to get into jobs that might, eventually, lead somewhere both interesting and remunerative.

But with more demand for places at university, the government is under pressure to provide funding — both to the universities to create more spaces, and to the students themselves to allow them to pay their tuition and other costs. Megan McArdle worries that pouring more money into the system isn’t the right answer:

The other day, I argued that maybe we should rethink our current policy of endlessly dumping more money into college education. It’s completely true that there is a big wage premium for having a college degree — but it does not therefore follow that we will make everyone better off by trying to shove every American through post-secondary (aka tertiary) education. We may simply be setting up college as a substitute for a high school diploma: a signal to employers that you can read and write, and are able to turn in scheduled assignments within a reasonable time frame. And in the process, excluding people who aren’t college-educated from access to decent jobs.

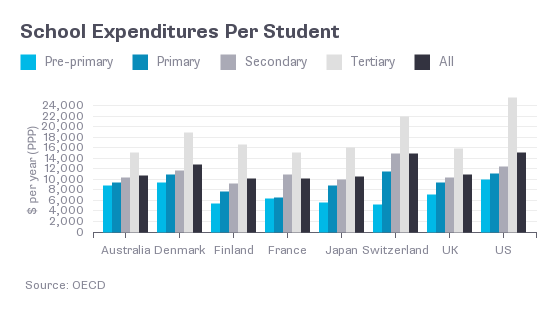

Predictably, this was not met with shouts of joy and universal admiration in all quarters. I was accused of just wanting to stick it to President Barack Obama, and also of wishing to deny the dream of college education that should be the birthright of every single American. I was also accused of being unfamiliar with the known fact that America woefully underinvests in education compared to other advanced nations.

It is true that I am unfamiliar with America’s woeful underinvestment in education, in the same way that I am unfamiliar with the tooth fairy, because both are legends with no basis in fact. American spending on education is in line with that of our peers in the developed world — a little higher than some, a little lower than others, but not really remarkable either way:

[…]

You can argue that there’s an inequality problem in our schools. In fact, I think there is obviously an inequality problem in our schools, but that the big problem is not at the college level, but rather in the primary and secondary schools that are overwhelmingly government-funded. And those disparities are also not primarily about the dollar amounts going into schools — Detroit spends well above the U.S. average per pupil, and yet one study found that half the population of the city was “functionally illiterate.”

Should we fix the issues with those schools? Absolutely — and doing so might mean spending more money. But that doesn’t mean that we need to increase the overall level of educational funding. It means that we need to identify ways to improve those underperforming schools, then find out how much more it would cost to implement those programs. It is just as likely that improvements will come from changing methods and reallocating resources as that they will require us to pour more money into failing institutions.

QotD: The libertarian movement

The libertarian or “freedom movement” is a loose and baggy monster that includes the Libertarian Party; Ron Paul fans of all ages; Reason magazine subscribers; glad-handers at Cato Institute’s free-lunch events in D.C.; Ayn Rand obsessives and Robert Heinlein buffs; the curmudgeons at Antiwar.com; most of the economics department at George Mason University and up to about one-third of all Nobel Prize winners in economics; the beautiful mad dreamers at The Free State Project; and many others. As with all movements, there’s never a single nerve center or brain that controls everything. There’s an endless amount of in-fighting among factions […] On issues such as economic regulation, public spending, and taxes, libertarians tend to roll with the conservative right. On other issues — such as civil liberties, gay marriage, and drug legalization, we find more common ground with the progressive left.

Nick Gillespie, “Libertarianism 3.0; Koch And A Smile”, The Daily Beast, 2014-05-30.

January 27, 2015

“Well, I certainly didn’t expect the Spanish Inquisition…”

How to think like a government bureaucrat

Robert Tracinski on the essential core of a control freak’s very being:

Here’s one of my favorite stories about how the mind of a government official works.

A few years ago, I was in a grocery store in Charlottesville when I overheard a conversation between two shoppers, one of whom was clearly in some position of authority (the City Council, I believe). This was right after the financial crisis. The real estate market had just collapsed, a whole bunch of local development project had just been canceled, and my wife was telling me about all the guys she knew in construction who were desperate for work. Yet here was this lady arguing for why the local government should not approve any new commercial building permits. The danger, she explained, was the prospect of “economic ghost towns,” retail areas where several shops had closed, hurting business for the others. Until these “economic ghost towns” were filled back up — whether anybody wanted them or not — there was no good reason to approve permits for new commercial construction.

I just couldn’t keep quiet and had to interrupt: Only in Charlottesville — a left-leaning university town — could an economic downturn be used as a reason to block new economic activity.

But you have to understand the outlook of those whose faith is the creed of government. Everything is proof of the need for more government power and control. The local economy is booming? Let’s hold back on building permits because we don’t want to grow “too fast.” The local economy is tanking? Let’s hold back on building permits because we don’t want “economic ghost towns,” or whatever. On the national level, in an economic collapse the government needs more money for “stimulus.” But if the economy is booming, that means we can afford higher taxes, right?

Shakespeare’s tender treatment of Catholicism

David Warren explains how he deduced that William Shakespeare was probably a Catholic:

Long before I became a Catholic, I realized that Shakespeare was one: as Catholic as so many of the nobles, artists, musicians and composers at the Court of Bad Queen Bess. I did not come to this conclusion because some secret Recusant document had fallen into my hands; or because I subscribed to any silly acrostic an over-ingenious scholar had descried, woven into a patch of otherwise harmless verses. My view came rather from reading the plays. The Histories especially, to start: which also helped form my reactionary politics, contributing powerfully to my contempt for mobs, and the demons who lead them. But with improvements of age, I now see an unmistakably Catholic “worldview” written into every scene that is indisputably from Shakespeare’s hand. (This recent piece by another lifelong Shakespeare addict — here — will spare me a paragraph or twenty.)

That our Bard came from Warwickshire, to where he returned after tiring of his big-city career, tells us plenty to start. The county, as much of Lancashire, Yorkshire, the West Country, and some other parts of England, remained all but impenetrable to Protestant agents and hitmen, well into Shakespeare’s time. Warwick’s better houses were tunnelled through with priest holes; and through Eamon Duffy and other “revisionist” historians we are beginning to recover knowledge of much that was papered over by the old Protestant and Statist propaganda. The story of Shakespeare’s own “lost years” (especially 1585–92) has been plausibly reconstructed; documentary evidence has been coming to light that was not expected before. Yet even in the eighteenth century, the editor Edmond Malone had his hands on nearly irrefutable evidence of the underground commitments of Shakespeare’s father, John; and we always knew the Hathaways were papists. Efforts to challenge such forthright evidence, or to deny its significance, are as old as the same hills.

But again, “documents” mean little to me, unless they can decisively clinch a point, as they now seem to be doing. Even so, people will continue to believe what they want to believe. In Wiki and like sources one will often find the most telling research dismissed, without examination, with a remark such as, “Against the trend of current scholarship.”

That “trend” consists of “scholars” who are not acquainted with the Bible (to which Shakespeare alludes on every page); have no knowledge of the religious controversies of the age, or what was at stake in them; show only a superficial comprehension of the Shakespearian “texts” they pretend to expound; assume the playwright is an agnostic because they are; and suffer from other debilities incumbent upon being all-round drooling malicious idiots.

Perhaps I could have put that more charitably. But I think it describes “the trend of current scholarship” well enough.

Now here is where the case becomes complicated. As something of a courtier himself, in later years under royal patronage, Shakespeare would have fit right into a Court environment in which candles and crucifixes were diligently maintained, the clergy were cap’d, coped, and surpliced, the cult of the saints was still alive, and outwardly even though Elizabeth was Queen, little had changed from the reign of Queen Mary.

The politics were immensely complicated; we might get into them some day. The point to take here is that the persecution of Catholics was happening not inside, but outside that Court. Inside, practising Catholics were relatively safe, so long as they did not make spectacles of themselves; and those not wishing to be hanged drawn and quartered, generally did not. It was outside that Queen Elizabeth walked her political tightrope, above murderously contending populist factions. She found herself appeasing a Calvinist constituency for which she had no sympathy, yet which had become the main threat to her rule, displacing previous Catholic conspirators both real and imagined. Quite apart from the bloodshed, those were interesting times, in every part of which we must look for motives to immediate context, before anywhere else. Eliza could be a ruthless, even fiendish power politician; but she was also an extremely well-educated woman, and in her tastes, a pupil of the old school.

Indeed the Puritans frequently suspected their Queen, despite her own Protestant protestations, of being a closet Catholic; and suspected her successor King James even more. A large part of the Catholic persecution in England was occasioned by the need to appease this “Arab spring” mob, concentrated in the capital city. Their bloodlust required human victims. The Queen and then her successor did their best to maintain, through English Bible and the Book of Common Prayer, the mediaeval Catholic inheritance, while throwing such sop to the wolves as the farcical “Articles of Religion.”

The question is not whether Shakespeare was one of the many secretly “card-carrying” Catholics. I think he probably was, on the face of the evidence, but that is a secondary matter. It is rather what Shakespeare wrote that is important. His private life is largely unrecoverable, but what he believed, and demonstrated, through the media of his plays and poems, remains freely available. He articulates an unambiguously Catholic view of human life in the Creation, and it is this that is worth exploring. The poetry (in both plays and poems) can be enjoyed, to some degree, and the dramatic element in itself, even if gentle reader has not twigged to this, just as Mozart can be enjoyed by those who know nothing about music. But to begin to understand as astute an author as was ever born, and to gain the benefit from what he can teach — his full benevolent genius — one must make room for his mind.

Maddy Prior’s “The Sovereign Prince”

The mariner is sailing

Sailing across the sea

Seeking out the enemy

Bringing spices back home to me

Spanish gold for the taking

At the harbour of Cadiz

Their fleet they left a-blazing

On the Ocean bed, stone cold, her cannons lie

Eldorado lies a shimmering

Shimmering like a mirage

Luring the merchant venturers

On a brutal grim and overlong voyage

Treasure laden galleons

Lemons, melons and quince

Strange exotic cargo

Gift and garlands fit for the Prince

And Gloriana rules with a woman’s wiles

Plays the coquette with politics and smiles

A computer for a brain in the body of a child

All temper and guile

And the girls on the beach

They are lying out of reach

They rub oil on their skins

And roll in the sand of hated Spain

And the girls in sidewalk bars

Drink their coffee, smoke their cigars

And laugh at the waiting maid

Who covers afraid of the Prince

And Gloriana in stiff starched lace

With pearls in her hair and thunder on her face

Screams with rage: Has God left this place?

There’s no God in this place

And the girls on the phone

Ring collect when they call home

And talk inconsequent

Will pass in a moment a thousand miles

And the girls in the airport lounge

Are awaiting the tannoy sound

For the flight to Brazil

With a couple of weeks to kill in the sun

And Gloriana so harsh and chaste

The soldier in her breast is raging at the waste

Of Victories lost and battles left unfaced

For want of such haste

And the girls in high-strapped shoes

With a tan they never lose

Wear the cross of gold

In memory of stories told in Sunday School

And the girls without the Church

Leave their lovers in the church

But seldom sleep alone

And think no more of Rome than a tourist town

And Gloriana sits slumped on the throne

Her head in her hands is weeping alone

Dreaming of the past and times that are gone

Dreams of time to come

And the mariner is sailing

Sailing across the sea

Seeking out the enemy

Bringing spices back home to me

Bring me my scallops shell of quiet

My staff of faith to walk upon

My scrip of joy, immortal diet

My bottle of salvation

My Gown of glory, hopes true gauge

And thus I’ll take my pilgrimage

(Raleigh)

QotD: Political parties and principles

Normally, [the voters] are suckered. The political class — the class of politicians, senior bureaucrats, self-interested lobbyists, and all their paid flunkeys in media and elsewhere — are much cleverer than “the people,” on political questions. “The people,” for their part, may be individually cleverer than they, but not, as a rule, on political questions, which don’t much interest the great majority of them. The political class have, in addition to whatever native smarts, plenty of experience manipulating “the people,” and the contempt required to be ruthless about it. In a fully-fledged “democracy,” it takes little sophistry for the bad guys to win. But the term is relative, and should the good guys win, it will be another victory for the politicians.

A few days ago, I found myself trying to explain this to a well-intended, rightwing person. He complained that the Conservative Party had turned its back on “conservative principles.” This struck me as an unfair allegation, for the party had never once in the history of Canada, whether at the provincial or Dominion level, embraced “conservative principles,” nor shown the slightest curiosity over what they might be. The purpose of a political party has nought to do with such “principles.” (This goes for all parties including, within five years of their founding, those founded on “principles.”) Rather it is to tax as much as they dare, and distribute the takings among their friends, while “nation building” — i.e. adding to the machinery of State. A party unclear on this essential “principle” of democracy (the one that defeats every other principle) might get itself elected by some fluke, but will not long retain power.

David Warren, “Hapless Voters”, Essays in Idleness, 2014-05-26.

January 26, 2015

John Hill, RIP

Gerald D. Swick on the death of one of the great wargame designers, the man who created Squad Leader:

If there is a heaven just for game designers, it has a new archangel. John Hill, best known for designing the groundbreaking board wargame Squad Leader, passed away on January 12. He was inducted into The Game Manufacturers Association’s Academy of Adventure Gaming Arts & Design Hall of Fame in 1978; Squad Leader was inducted into the HoF in 2004.

His many boardgame designs include Jerusalem (1975), Battle for Hue (1973), Battle for Stalingrad (1980) and Tank Leader (1986 and 1987), but John was always a miniatures gamer at heart, and anyone who ever got to play a game on his magnificent game table considered themselves lucky. Squad Leader was originally intended to be a set of miniatures rules, but the publisher, Avalon Hill, asked him to convert it to a cardboard-counters boardgame design. His Civil War miniatures rules Johnny Reb were considered so significant that even Fire & Movement magazine, which primarily covered boardgames, published a major article on the JR system. Most recently John designed Across A Deadly Field, a set of big-battle Civil War rules, for Osprey. He completed additional books in the series for Osprey that have not yet been published.

Tsar Vladimir I is making “dangerous history”

Austin Bay looks at the risky but rewarding path of aggression and propaganda undertaken by Vladimir Putin:

Russian president Vladimir Putin made dangerous history in 2014. His invasion of Crimea and subsequent annexation of the peninsula shredded the diplomatic agreements stabilizing post-Cold War Eastern Europe.

Then Putin ignited a low-level war in Eastern Ukraine. Despite a September 2014 ceasefire agreement, Putin’s overt covert war-making continues in Eastern Ukraine. The Kremlin has concluded that Western leaders, European and American, are weak and indecisive.

Putin, unfortunately, knows how to use specific tactics in operations designed to achieve his strategic goals.

Military analysts typically recognize three levels of conflict: the tactical, the operational and the strategic. The categories are general, and distinctions often arguable. Firing an infantry weapon, however, is a basic tactical action. Assassinating Austrian royalty with a revolver is a tactical action, but one that in 1914 had strategic effect (global war). U. S. Grant’s Vicksburg campaign (1862-63) consisted of several Union military operations around Vicksburg (many unsuccessful). The campaign’s concluding operation, besieging Vicksburg, was an operational victory that gave the Union a strategic military and economic advantage: control of the Mississippi.

Putin’s Kremlin uses propaganda operations to blur its responsibility for tactical attacks in Ukraine. International propaganda frustrates Western media scrutiny of Russia’s calculated tactical combat action. Local propaganda targets Eastern Ukraine. Earlier this month, Ukrainian journalist Roman Cheremsky told Radio Free Europe that despite suffering criminal bullying by pro-Russian fighters, Kremlin “disinformation” is convincing Eastern Ukraine’s Russian speakers that Ukrainian forces are “bloodthirsty thugs.”

[…]

Oil’s price plunge, however, has also slammed Putin, threatening the genius with political and economic problems that, if prices remain low, could erode his personal political power. Energy revenue declines do far more damage to Putin than the economic sanctions Western governments have imposed.

So what’s a brilliant, innovative, thoroughly unscrupulous and utterly amoral strategist to do?

According to the AP, this week (Jan. 20), Iran and Russia signed “an agreement to expand military cooperation.” Iran and Russia are old antagonists, but given current circumstances vis a vis the U.S. and Saudi Arabia, Tehran and Moscow may be following an old Machiavellian adage: “the enemy of my enemy is my friend.” The deal includes counter-terror cooperation, military training and “enabling each country’s navy to use the other’s ports more frequently.”

For years Iran has sought Russian air defense weapons, presumably to thwart a U.S. strike on its nuclear facilities. However, the agreement’s naval port clause attracts my interest. About a third of the globe’s exported oil moves on tankers through the Persian Gulf’s Indian Ocean outlet, the Strait of Hormuz. To spike oil prices, Iran often threatens to close Hormuz. If Iran actually tried to shut the Strait, Western nations have assured Gulf Arab oil producers that they will respond militarily.

Al Stewart performs “Year of the Cat” at the Royal Albert Hall

Published on 25 Sep 2014

On October 15, 2013 Al Stewart performed his classic “Year Of The Cat” album in its entirety for the first time ever in London at the Royal Albert Hall, with a band containing many of the musicians who played on the original recording.

Here is Al performing the title song with original band members Peter White (piano, musical director), Tim Renwick (el gtr), Stuart Elliott (drums) and Phil Kenzie (alto sax)- along with Mark Griffiths (bass), Dave Nachmanoff (gtr) and Joe Becket (perc).

Balancing the art and the science in winemaking

In Cosmos, Andrew Masterson investigates what is still an art and what has been codified as science:

“With commercial yeast you get certainty – you can sleep at night,” says Bicknell. “But how do you make wine more interesting? You exploit the metabolic processes of different yeast species.”

Bicknell’s faith in wild yeasts adds stress at fermentation time, but the pay-off is multi-award-winning wines regularly acknowledged as some of the best in Australia. “The wines do taste different, even if there’s no way you can show that statistically,” Bicknell says. “The only way to really know is to taste.”

Exploiting the diverse and fluctuating populations of wild yeasts found on the plants, fruit and in the air of vineyards is “the new black” (not to mention red and white) in oenology. The practice is becoming more commonplace among artisan winemakers. Even some of the giant commercial wine corporations are investing in the method.

Wild fermentation, says Bicknell, represents the intersection of science, craft and philosophy. But it could also form the basis of a profound shift in the narrative of wine. The more we study winemaking’s microbes, the more it appears they might explain one of the wine industry’s most beloved, but vaguest, terms: terroir.

“Terroir is a wonderful marketing term,” says David Mills, a microbiologist at UC Davis, who studies microbes in wine. “But it’s not a science.”

The French word terroir is difficult to translate. The closest translation is “soil”, but that is just one of its components. Terroir connotes the unique sense of place – the soils, the topography and the microclimate. It’s what makes the wines of Bordeaux or Australia’s Coonawarra so distinctive, and so inimitable.

Sommeliers like Ren Lim, former captain of the Oxford University Blind Tasting Society (and a PhD biophysics student) will tell you merely from swirling a mouthful of Cabernet Sauvignon which Australian winery produced it.

“The ones from Margaret River often give off a more pronounced green pepper note, a note found commonly in Cabernets grown in regions which experience pronounced maritime influences. Coonawarra Cabernets are somewhat different and unique in their own way. They are often minty and have a eucalyptus or menthol note in addition to the usual ripe blackcurrant notes. The green pepper note is often suppressed under the menthol notes. Nonetheless, the Cabernet structure remains in both these wines.”

It’s a feat that Mills does not question. “I don’t doubt regionality exists, but what causes it is a whole other set of issues.”

QotD: Against the Human Development Index (HDI)

[W]hat exactly is the HDI? The one-line explanation is that it gives “equal weights” to GDP per capita, life expectancy, and education. But it’s more complicated than that, because scores on each of the three measures are bounded between 0 and 1. This effectively means that a country of immortals with infinite per-capita GDP would get a score of .666 (lower than South Africa and Tajikistan) if its population were illiterate and never went to school.

So what are the main problems with the HDI?

1. I can see giving equal weights to GDP per capita and life expectancy. But education? As a professor and a snob, I understand the appeal (though a measure of opera consumption would be even better). But in terms of the actual if not professed values of normal human beings, televisions and cars are a lot more important than books.

2. When you take a closer look at the HDI’s education measure, it’s especially bogus. 2/3rds of the weight comes from the literacy rate. At least that’s not ridiculous. But the other 1/3 comes from the Gross Enrollment Index — the fraction of the population enrolled in primary, secondary, or tertiary education. OK, I feel a reductio ad absurdum coming on. To max out your education score, you have to turn 100% of your population into students!

3. The HDI purportedly gives equal weights to three different outcomes, but bounding the results between 0 and 1 builds in a massive bias against GDP. GDP per capita has grown fantastically during the last two centuries, and will continue to do so. In reality, there’s plenty of room left for further improvement even in rich countries. But the HDI doesn’t allow this. Since rich countries are already close to the upper bound, the HDI effectively defines their future progress on this dimension out of existence.

To a lesser extent, the same goes for life expectancy: While it’s roughly doubled over the last two centuries, dying at 85 is not, contrary to the HDI, approximately equal in value to immortality.

The clear winners from this weighting scheme, of course, are the literacy and enrollment measures, both of which have upper bounds that are imposed by logic rather than fiat.

4. The ultimate problem with the HDI, though, is lack of ambition. It effectively proclaims an “end of history” where Scandinavia is the pinnacle of human achievement. […] Scandinavia comes out on top according to the HDI because the HDI is basically a measure of how Scandinavian your country is.

Bryan Caplan, “Against the Human Development Index”, Econlog, 2009-05-22.