If you haven’t heard of the original “Bechdel Test“, here’s the gist:

The Bechdel test is used to identify gender bias in fiction. A work passes the test if it features at least two women who talk to each other about something other than a man. Commentators have noted that a great proportion of contemporary works fail to pass this threshold of representing women. The test was originally conceived for evaluating films, but has since been applied to other media.

Have you ever noticed that articles in the media about female scientists always include details they would never have if the article was about a man? In too many cases, these details predominate over the actual scientific work of the person being profiled. Christie Aschwanden suggests that we adopt a variant of the Bechdel test for science writing:

It’s time to stop this nonsense. We don’t write “Redheads in Science” articles, so why do we keep writing about scientists in the context of their gonads? Sexism exists, and we should call it out when we see it. But treating female scientists as special cases only perpetuates the idea that there’s something extraordinary about a woman doing science.

So Finkbeiner has adopted a new approach. “I’m going to cut to the chase, close my eyes, and pretend the problem is solved; we’ve made a great cultural leap forward and the whole issue is over with,” she says. “And I’m going to write the profile of an impressive astronomer and not once mention that she’s a woman.” In other words, “I’m going to pretend she’s just an astronomer.”

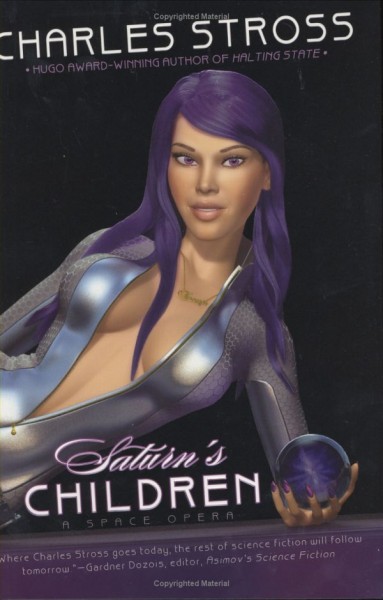

It’s a fine idea. In the spirit of the Bechdel test, a metric that cartoonist and author Alison Bechdel created to measure gender bias in film, I’d like to propose a Finkebeiner test for stories about women in science. The test could apply to profiles of women in other fields, too.

To pass the Finkbeiner test, the story cannot mention

- The fact that she’s a woman

- Her husband’s job

- Her child care arrangements

- How she nurtures her underlings

- How she was taken aback by the competitiveness in her field

- How she’s such a role model for other women

- How she’s the “first woman to…”

Here’s another trick. Take the things that are said about a female subject and flip them around as if they were said about a male. If they sound ridiculous, then chances are good they have no business in the story. For instance, in his Guardian profile of preeminent physicist Lisa Randall, John Crace writes, “No matter how much she bends time, there’s no escaping the fact that she’s just turned 43 and that if she wants to have kids she’s going to have to get on with it soon.” No one would possibly write such a thing about a man of her age and status.