World War Two

Published 10 Apr 2025February 1931 sees unprecedented chaos in Germany’s parliament as Nazis and Communists stage a dramatic walkout, ironically enabling democratic parties to pass reforms unopposed. Meanwhile, Hitler pushes eastward expansion, Berlin bans extremist newspapers — including Goebbels’ Der Angriff — and Röhm militarizes the Nazi SA. With democracy under strain and political extremes emboldened, what’s next for the Weimar Republic?

(more…)

April 11, 2025

Nazis and Communists Unite Against Weimar – Rise of Hitler 14, February 1931

March 28, 2025

The Man Hitler Needs for Civil War, Ernst Röhm, Returns!

World War Two

Published 27 Mar 2025January 1931 starts with violence, economic collapse, and Nazi upheaval in Germany. Hitler secretly meets with army chief Kurt von Hammerstein-Equord, while Ernst Röhm returns to take command of the Nazi paramilitary SA. As hundreds of thousands of miners face mass layoffs and brutal crackdowns, the republic’s future hangs in the balance — how long can democracy hold on?

(more…)

March 22, 2025

How One Movie Drove Hitler’s Men Crazy – Rise of Hitler 12, December 1930

World War Two

Published 20 Mar 2025December 1930 plunges Germany deeper into chaos. Nazis and Communists join forces against Chancellor Brüning’s emergency decrees, while a shocking court decision boosts Hitler’s power. Violent riots erupt over the film All Quiet on the Western Front, and police uncover a terrifying communist bomb plot aimed at sparking civil war. With extremism rising, is Weimar democracy heading for disaster?

(more…)

February 14, 2025

Disarmament Talks, Budget Battles, and Student Duels – Nov 1930

World War Two

Published 13 February 2025November 1930 sees Germany caught between political instability and international disputes. Brüning fights to pass his controversial budget while Germany’s push for global disarmament meets French resistance and Nazi outrage. Meanwhile, Hitler restructures the SA and SS, student duels make headlines, and Berlin’s police chief is attacked in court.

(more…)

January 30, 2025

Hitler Testifies, Brüning Battles On – Rise of Hitler 10, October 1930

World War Two

Published 28 Jan 2025October 1930 brings more unrest to Weimar Germany. Chancellor Brüning survives no-confidence votes, while Nazi and Communist clashes escalate into chaos. Berlin sees mass protests, Jewish businesses attacked, and rumors of a Nazi-Soviet conspiracy swirl.

(more…)

January 10, 2025

Germany Votes – Rise of Hitler 09, September 1930

World War Two

Published 9 Jan 2025The September 1930 elections reshape Germany’s political landscape. With surging support for extremists like the Nazis and Communists, and declining votes for democratic parties, Weimar faces a deeply polarized future. This episode breaks down the results, voter shifts, and what this means for the Republic.

(more…)

December 20, 2024

Election Fever – Rise of Hitler 08, August 1930

World War Two

Published 19 December 2024August 1930 brings Germany to a critical juncture as parties prepare for the September elections. Amid street violence, bans on political uniforms, and soaring unemployment, the stakes couldn’t be higher. This episode unpacks the campaign strategies, shifting alliances, and rising tensions shaping the Republic’s future.

(more…)

December 8, 2024

President Hindenburg dissolves the Reichstag – Rise of Hitler 07, July 1930

World War Two

Published 7 Dec 2024July 1930 sees the Weimar Republic facing unprecedented turmoil. From Brüning’s budget crisis and the Reichstag‘s dissolution to Nazi and Communist clashes with state governments, Germany braces for a pivotal election in September. This episode unpacks the month’s chaos, political maneuvers, and the rising tensions tearing the Republic apart.

(more…)

November 17, 2024

Nazi Uniforms banned across three States – Rise of Hitler 06, June 1930

World War Two

Published 16 Nov 2024In June 1930, the Weimar Republic faces escalating tensions as Nazi uniforms are banned in three states to curb political violence. The French withdrawal from the Rhineland marks a major milestone while Saxony’s elections leave the state in political deadlock. Meanwhile, Chancellor Brüning battles to save his government amidst growing financial turmoil and party divisions.

(more…)

November 3, 2024

Unholy Alliance topples Saxony – Rise of Hitler 05, May 1930

World War Two

Published 2 Nov 2024May 1930 brings political upheaval to the Weimar Republic, with the French deciding to leave the Rhineland, violent clashes between Communists and Nazis, and a surprising alliance that dissolves Saxony’s government. See how these events unfold and shape Germany’s current political landscape.

(more…)

October 20, 2024

Nazi Conspiracies Everywhere – Rise of Hitler, April 1930

World War Two

Published 19 Oct 2024Join us for the May 1930 edition of the Weimar Wire, where we cover violent communist Youth Day demonstrations, a tough first month for new German chancellor Bruning, crazy Nazi conspiracy theories, and a whole lot more.

(more…)

October 6, 2024

Will the President Abolish Democracy? – Rise of Hitler 03, March 1930

World War Two

Published 5 Oct 2024In the March 1930 Issue of the Weimar Wire Chancellor Muller resigns, the coalition government collapses, and Heinrich Brüning tries to build a new cabinet amidst street violence and political chaos. With the Nazis and Communists gaining strength, will Brüning succeed, or is the Weimar Republic heading for disaster?

(more…)

September 22, 2024

How to Make a Nazi Martyr – Rise of Hitler 02, February 1930

World War Two

Published 21 Sep 2024In this issue of the Weimar Wire, we dive deep into the critical events of February 1930. Political violence continues to claim victims on the streets, the future Polish-German relationship is up in the air, the other powers bicker at the London Naval conference, all the while, the current government struggles to fill a ginormous budget hole.

(more…)

September 8, 2024

Hitler’s Victory in Thüringen – Rise of Hitler 01

World War Two

Published 7 Sep 2024In this issue of the Weimar Wire, we dive deep into the critical events of January 1930. Political violence in the streets, uncertainty over the nation’s very character and Nazis entering a governing coalition provide a veritable treasure trove of political intrigue, hidden aspirations, and grand schemes.

(more…)

November 9, 2023

Remembering Weimar

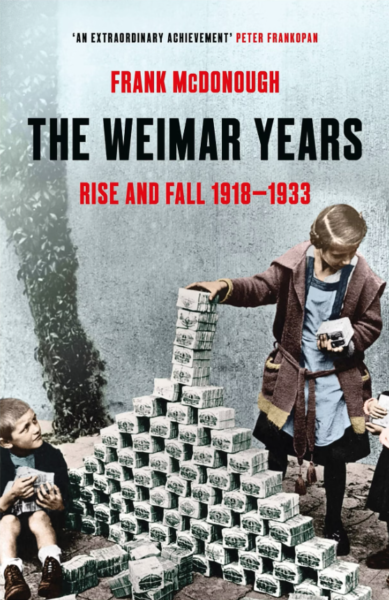

In The Critic, Darren O’Byrne reviews some recent books on German society between the Armistice of 1918 and the rise of Hitler, including Frank McDonough’s The Weimar Years: Rise and Fall 1918–1933.

One of the latest additions to the canon is Frank McDonough’s The Weimar Years (1918–33). A prequel to his two-volume narrative history of the Third Reich, The Hitler Years, it sets out to explain the Nazis’ rise to power by examining the reasons why democracy failed in Germany. Like the earliest histories of the period, the Republic is not examined on its own terms but rather as a kind of backstory to what followed, the numerous crises that befell it being used to explain the ultimate catastrophe.

Structured chronologically, the book provides a devastating, play-by-play account of why, for McDonough, democracy stood little chance in Germany. Defeat in World War I, the Kaiser’s abdication and the humiliating terms of the Versailles treaties challenged the legitimacy of the Republic from the start, as did its failure to contain political violence. Crippling inflation and mounting government debt, exacerbated by the obligation to pay reparations to the Allies, hampered German economic recovery from the start and threatened to wipe out the middle classes.

A degree of economic stability did return in the mid-1920s, but the country experienced its second “once-in-a-lifetime” economic crisis in the early 1930s, causing further instability and ultimately paving the way for Hitler. It’s a well-known story, skilfully retold for a contemporary audience by one of the foremost authorities on modern German history.

Does McDonough tell us anything we didn’t already know? The answer, in short, is no. In comparison to other recent histories of the period, more attention is paid here to high politics than Weimar’s cultural achievements, which are mentioned, but this tends to disrupt the flow of what is otherwise a high-paced, edge-of-the-seat political history of Germany’s first democracy. Despite being nearly 600 pages in length, the book’s focus is quite narrow, with little attention paid to what was happening below the national level in the federal states.

This may seem like an inane criticism. Who, after all, would demand to read more about Buckinghamshire in a political history of interwar Britain? However, the Weimar Republic, like Germany today, was a federation. Understanding what was happening in states like Prussia, which contained three-fifths of Germany’s population, is crucial to understanding the country as a whole.

Indeed, McDonough places some of the blame for Weimar’s collapse on the Social Democrats, who he argues should have participated in more national governments. Prussia was governed by an SPD-led coalition for most of the Weimar years, though, yet the Republic still fell. McDonough sees another reason for this fall in the failure to purge the military and civil service of hostile elements.

Again, Prussia replaced a considerable number of these officials with others loyal to the new democratic order, yet the Republic still fell. The book’s rigid focus on high politics, in short, obscures an understanding of the more structural reasons why democracy failed.

Unlike most history books, however, The Weimar Years is a genuine page-turner, full of lessons for those who want to learn something about the present from the past. It’s also a beautiful book to hold, full of period photos that help bring the story alive. This all makes the book worth reading, even if there’s not much in it that can’t be found in other histories of the period.