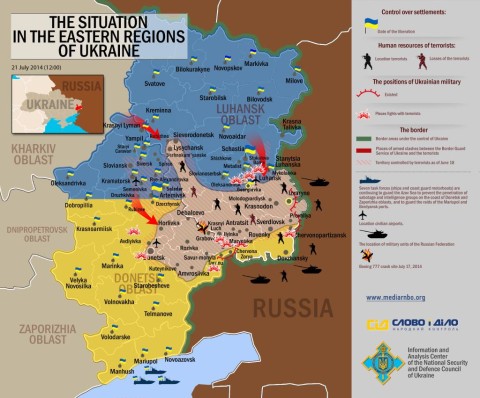

Current situation map released on Twitter by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine:

September 7, 2014

September 5, 2014

NATO – “they spent all their money on buying Ferraris and now they have no gas money”

Philip Ewing reports on the chances of improved military “readiness” among the NATO allies:

With President Barack Obama in Europe this week for a major NATO summit, the White House hopes the growl of the Russian bear on Europe’s eastern flank means the moment is right for some long-sought reforms to the alliance. But the outlook appears dim for anything beyond incremental steps at best.

The major reason is one that has frustrated policymakers over the past several administrations: Most European nations would love a stouter defense structure — so long as they don’t have to pay for it.

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization requires that member nations devote at least 2 percent of their economies to defense spending, yet today only four do: the U.S., Britain, Greece and Estonia. Although this week’s summit in Wales appears likely to yield a “pledge” in support of increased spending in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, no one expects a serious effort from members other than those most directly threatened, including Latvia, Lithuania and Poland.

[…]

Obama and U.S. officials also are focused on bolstering European military “readiness,” particularly as U.S. spending declines. NATO relies on the U.S. for critical military capabilities such as surveillance, in-flight refueling and transportation. European militaries field top-rate troops, ships and aircraft but keep only weeks’ or even days’ worth of munitions on hand. In NATO’s 2011 campaign against Libya, many nations ran out of munitions and the French began dropping concrete bombs.

“It’s sort of like they spent all their money on buying Ferraris and now they have no gas money,” Benitez said. “There are many allies that literally aren’t flying their planes because they can’t afford to. They have very advanced fleets, but their fleets aren’t leaving port because they can’t afford to.”

September 2, 2014

Tsar Vladimir I

One of the problems that Western politicians have in dealing with Vladimir Putin is that they can’t decide what he wants or even why he wants them. They’re struggling because they keep misreading individual actions as being either nationalistic or ethnic, when they should really be described as “imperialistic”. Putin is trying to recreate the old USSR, but without the Communist Party running things — he’s trying to recreate Imperial Russia:

Americans have been grasping to find explanations for Russian President Vladimir Putin’s serial aggressions in Europe. We keep searching for bumper stickers we can understand, so we gravitate to simple explanations like “geopolitics” or “nationalism,” not least because such notions promise solutions. (If it’s about geopolitics, cutting a deal with Putin will stop this; if it’s about nationalism, it’ll burn itself out when Putin has recaptured enough ethnic Russians around his borders.)

And, of course, there’s always “realism.” In this month’s Foreign Affairs, John Mearsheimer argues the Russo-Ukraine war is basically the West’s fault. (We expanded NATO, we supported the Maidan protesters, we were generally just mean to Russia, etc.) It’s a classic Mearsheimer piece: a beautifully-written, attention-seeking exercise that insists on the brilliance of realists while bucking the innate moral sense of most normal human beings. (Consider, for example, his 1993 Deep Thoughts about how maybe it would be good for Ukraine and Germany to develop active nuclear weapons programs.)

That doesn’t mean I disagree with the overall evaluation that America’s Russia policy since 1992 — insofar as we’ve had one — has been remarkably obtuse. (That pretty much describes most of our foreign policy since the end of the Cold War, but I will not digress here.) I, too, objected to expanding NATO, deplored the arrogance of people like Madeleine Albright, and lamented the repeated lost opportunities to bring Moscow closer to the Western family to which it belongs by both heritage and history.

Very little of what’s happened in the past 20 years, however, has much to do with what’s going on in Ukraine right now. And nothing excuses Russia’s war against a peaceful neighbor, especially not arid theories of realism or flawed historical analogies.

Putin is not a realist: very few national leaders are. Realism is much loved by political scientists, but actual nations almost never practice it. Nor is Putin a nationalist: indeed, he hardly seems to understand the concept, or he would not have embarked on his current path.

August 31, 2014

Combat situation in Ukraine

Current situation map released on Twitter by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine:

August 28, 2014

None dare call it an invasion

The battles between Ukraine forces and Russian-backed rebels were one thing: you could make a case for it being a “local” issue if you didn’t want to draw attention to it (for fear the Russians might cut off your natural gas supply). It’s quite a different thing when the Ukrainians are fighting Russian soldiers rather than irregulars and paramilitaries:

Russian forces in two armored columns captured a key southeastern coastal town near the Russian border Thursday after Ukrainian forces retreated in the face of superior firepower, a Ukrainian military spokesman said.

The two Russian columns, including tanks and armored fighting vehicles, entered the town of Novoazovsk on the Sea of Azov after a battle in which Ukrainian army positions came under fire from Grad rockets launched from Russian territory, according to the spokesman, Col. Andriy Lysenko.

“Our border servicemen and guardsmen retreated as they did not have heavy equipment,” Lysenko said in a statement.

Ukrainian authorities have denounced the latest fighting as a Russian invasion of their territory, intended to prop up pro-Moscow separatists who have been losing ground to Ukrainian forces and to open a new front in the southeastern corner of Ukraine.

Ukrainian officials said earlier that Ukrainian troops were battling combined Russian and separatist forces on the new southern front around Novoazovsk, about eight miles west of the Russian border. The Ukrainian military also said Russian troops were increasing surveillance from northern Crimea, the autonomous Ukrainian peninsula annexed by Moscow in March.

Among western countries, Canada (of all places) has become snarky about the situation:

Geography can be tough. Here’s a guide for Russian soldiers who keep getting lost & ‘accidentally’ entering #Ukraine pic.twitter.com/RF3H4IXGSp

— Canada at NATO (@CanadaNATO) August 27, 2014

July 23, 2014

Closing the Eastern Ukraine pocket

CDR Salamander links to a recent Ukrainian report that seems to show how far the Ukraine forces have come since May in reclaiming territory from the “separatists”:

Look at what has happened in the last two months.

1. Ukraine secured its maritime territory.

2. Ukraine managed to re-establish control over most of its borders – though in a thin salient in some places. Not firm control as we know traffic is getting through, but at least partial control to the point they are willing to claim it.

3. They are pushing to widen the salient in the south while increasing its SE bulge, pushing north along the Russian border.

4. From the north, they are pushing south along the Russian border.

5. Yes kiddies, we have a classic pincer movement to envelope a pocket of the enemy, nee – a double envelopment at that. As a matter of fact, a secondary double envelopment is about to take place in that middle thumb centered on Lysychansk – or at least there is an opportunity for one.Cut off the Lysychansk based separatists there while at the same time cutting off their unopposed access to the Russian border – and then you can destroy the pro-Russian separatists piecemeal at your leisure.

A quick Google search for “ATO progress map” also turned up this map posted to Twitter a couple of days ago by Viktor Kovalenko:

As the original CDR Salamander post points out, these are based on claims by one side so apply whatever filters you feel are needed to counteract any PR or propaganda bias.

July 18, 2014

Despite reports, Canada is not “donating” surplus CF-18 fighters to Ukraine

In the Ottawa Citizen, David Pugliese says there’s little chance of any such transaction taking place:

Media in Russia are reporting that Canada will provide for free surplus CF-18 fighter jets to Ukraine’s military. In addition, an offer has been made to provide RCAF personnel to train Ukraine pilots on the aircraft, according to the reports.

Officials with the Department of National Defence officials as well as Defence Minister Rob Nicholson’s spokesperson, however, tell Defence Watch that is not the case.

“This report is false,” said Johanna Quinney, the minister’s spokeswoman.

Unlike the vast inventory of aircraft maintained by the US Air Force, the RCAF does not have thousands of acres of desert littered with functional-but-unused aircraft. Any surplus CF-18 airframes are candidates for cannibalization to keep the rest of the fleet airworthy. This almost certainly means that these aircraft in question are not in a flyable condition, so their immediate military value — to Ukraine or other nations — is close to zero. Add in the required time, labour, and parts to bring them to operational levels and it probably amounts to a negative value.

Update: On Facebook, Chris Taylor points out that there’s a difference between what most militaries might consider surplus and what the Canadian Forces consider surplus:

Canada never retires weapon systems before they become antiques. By Ottawa reckoning, there’s at least 30 years left in the CF-18s. Pay no attention to airframe fatigue or metallurgical studies, these are airy-fairy abstractions that will bend to the will of the PMO.

Russia’s foreign policy just went over the ledge

Tom Nichols discusses what the destruction of Malaysian Airlines flight 17 means for Russia:

Here’s what the shootdown of Malaysian Airlines Flight 17 means: Russia, with Vladimir Putin at the wheel, just drove off the edge of a cliff.

Now, by this I don’t mean that the United States and the European Union are going to charge in with a new round of sanctions, provide lethal aid to Ukraine, patrol the skies of Ukraine, or anything of that nature. The West didn’t react in time, or with enough resolve, to the initial invasion and partition of Ukraine last spring, and there’s no reason to think our reaction will be any more effective or resolute this time. It would be reassuring to think America and Europe will now fully engage on the problem of Russian aggression, but it’s unlikely.

As far as Russia’s future is concerned, however, it doesn’t matter. The moment Flight 17 exploded was the moment that Putin’s foreign policy officially went over the ledge, and with it his dreams of restored Russian greatness.

Until now, Moscow claimed it was protecting the interests of Russian-speakers in eastern Ukraine. That was nonsense right from the start, but it was nonsense the Americans and Europeans decided they could live with, as galling as it was. (Who, after all, protects the rights of Russians in Russia? Certainly not Putin.) The West looked away as Putin seized Crimea, as we conveniently convinced ourselves that this was some odd ethnic quarrel in which we had no say. Now that a civilian airliner has been blown out of the sky by a Russian missile, however, there can be no further denial that Russia is actively pursuing a major proxy war against its neighbor in the center of Europe, and with a brutality that would make the now-departed marshals of the old Soviet high command smile with approval. This is no longer a war on Ukraine, but a war on the entire post-Cold War international order.

June 7, 2014

Europe should bear more of the costs of their own defence

The American government is being called upon to re-assure NATO allies with suddenly volatile borders (that is, those near Russia and Ukraine). That re-assurance is to take the form of greater US military involvement in the Eastern European sector of NATO. The Cato Institute’s Doug Bandow says that this is actually an opportunity for those NATO countries to start living up to their own obligations to maintain viable defensive forces:

The Baltic States are screaming for enhanced military protection. Yet Estonia devotes just two percent of its GDP to defense. Latvia spends .9 percent of its GDP on the military. Lithuania commits .8 percent of its GDP on defense.

Poland may be the country most insistent about the necessity of American troops on along its border with Russia. To its credit, Poland has been increasing military outlays, but it still falls short of NATO’s two percent objective. Warsaw spent 1.8 percent last year.

Only Great Britain and Greece joined Estonia in hitting the two percent benchmark. France and Turkey fall short. Germany comes in at 1.3 percent. Overall NATO hit 1.6 percent last year. America was 4.1 percent.

Per capita military spending is even more striking. My Cato Institute colleague Chris Preble figured that to be $1896 for Americans. And $399 for Europeans. A disparity of nearly five to one.

Unfortunately, President Barack Obama doesn’t appear to recognize the dependency problem. At West Point he merely indicated that “we are now working with NATO allies” to reassure the Eastern Europeans. “We”?

Poland expects to hit 1.95 percent of GDP this year. Latvia and Lithuania promised to up outlays to meet the two percent standard — in a few years. No one else is talking about big spending increases. Absent is any commitment to move European troops to NATO’s eastern borders.

Nothing will change as long as Washington uses the defense budget as a form of international welfare. The more the president “reassures” U.S. allies, the less likely they are to do anything serious on behalf of their own defense.

Canada is also a military freeloader on US resources. While our NATO commitments imply we’ll spend 2% of GDP on our defences, we spend 1.3% in 2012, and the Department of National Defence is struggling to reduce spending below previous years’ outlays to meet the federal government’s overall budget balancing plans.

Update, 8 June: Stephen Gordon posted a Twitter update that puts Canadian military spending into a bit of perspective

Increase GST by 3 ppts? RT @pmlagasse: If Cda to meet 2% NATO request, defence budget ~0 $40b/yr. Good to know where extra $20b wd come from

— Stephen Gordon (@stephenfgordon) June 8, 2014

May 22, 2014

The Ukrainian army and corruption

At Defense One, Sarah Chayes says that the pitiful state of the Ukraine’s armed forces is a case study in how corruption can hollow out a nation’s defences:

Here’s a contrast that sums up the David and Goliath aspect of the Ukraine crisis. Picture the sleek, white-hulled vessel Vladivostok, one of two Mistral class warships France is selling to Russia, and compare the bedraggled tents some Ukrainian soldiers sleep in with donations of food jumbled outside and rain-soaked blankets drying over a brushwood fire.

The Russian behemoth outmatches its smaller and weaker neighbor, intrinsically. But the gap did not have to be so stark. Nor did the task of confronting irregular separatist militias have to be so hard. At fault is what drove the Maidan protesters to the streets in the first place: corruption. Ukraine is a case study in one of the ways corruption threatens international security: it guts armies. It makes them useless for defending their borders and as allies. United States officials in their rush to aid the Ukrainian military should resist the temptation to turn a blind eye to lingering venality. Ukraine’s future depends on some tough love.

“A modern country cannot exist without a modern army,” Ukraine’s Deputy Defense Minister Petro Mehed said at a press conference last month announcing a major military overhaul. “In recent years, [the Ukrainian] army has been systematically destroyed and disarmed, and its best personnel dismissed.”

In a 2012 analysis Leonid Polyakov, another senior defense official, detailed the corrupt workings with remarkable candor. Chronic underfunding “enhanced the role of the human factor” in choosing among operational priorities. Ostensibly outdated equipment was sold “at unreasonably understated prices” in return for kickbacks. Officers even auctioned off defense ministry land. Gradually, Kyiv began requiring the military to cover more of its own costs, forcing senior officers into business, “which is…inconsistent with the armed forces’ mission,” and opened multiple avenues for corruption. Commanders took to “using military equipment, infrastructure, and…personnel [to] build private houses, [or] make repairs in their apartments.” Procurement fraud was rife, as were bribes to get into and through military academies, and for desirable assignments.

H/T to Tony Prudori for the link.

May 6, 2014

What is Canada’s interest in Ukraine?

In the Globe and Mail, J.L. Granatstein spells out why the situation in Ukraine deserves the attention of the Canadian government:

Canada has no direct economic or political interest in Ukraine. Canadians of Ukrainian descent surely do, but Canada’s national interests cannot and should not be determined by components of our multicultural society. Our national interests are, first and foremost, the protection of our people, territory, and national unity, co-operation with our great neighbour and economic growth and well-being.

But there is another precept in any list of Canadian national interests – co-operation with our allies in the defence and advancement of freedom and democracy. Canadians have fought wars for that principle in the past, and more than 100,000 Canadians have died for it. The Russian threat to Ukraine surely is a challenge to this Canadian national interest.

Nothing here suggests that Ukraine is a perfect democracy threatened by an expansionist Russia. The Kiev government has been a badly run kleptocracy, corrupt, and incompetent, as the pathetic present state of its military suggests. The toppling of the regime of Viktor Yanukovych was a populist, largely democratic revolt, led by democratic forces but with a sprinkling of far right nationalist groups. The presence of these quasi-fascist and anti-Semitic elements provided the Vladimir Putin government in Moscow with the pretext it needed to rescue Crimea from the clutches of anti-Russia forces and to claim, as it backs pro-Moscow elements in eastern Ukraine, that it is supporting the legitimacy of the Yanukovych government.

[…]

The Canadian government has not received much praise for its tough-talking stance. Though tepidly supported by the Opposition parties, Ottawa’s position has widely been seen as pandering to the large Ukrainian-Canadian vote, and many on the left and right have attacked the ultra-nationalist tilt of the “democratic” groups in Ukraine or called for isolationism to be the only proper Canadian stance. Their strictures may even be correct, and certainly none can deny that the Harper government plays domestic ethnic politics with skill.

But there remains that Canadian national interest in supporting freedom. Ukraine is no democracy but it might become one; it deserves the opportunity to find its place as part of the European Union, as a neutral state trading both east and west, or even as a federation with its eastern provinces leaning to Russia. But whatever the choice, that ought to be made by Ukrainians, not by Moscow’s agitators. The Canadian political response, while not exactly measured in its decibel count, has been appropriate, and so too are the Canadian and allied military moves. Mr. Putin has behaved like the KGB thug he was and remains, and the caution sign needed to be displayed lest he look beyond Ukraine.

April 27, 2014

Why the EU did not overtly support the Maidan protests

Ace sums it up nicely:

Why wasn’t the EU doing “more” to pressure Yanukovych, Putin’s choice for President?

Here’s the thing: Because the EU was thinking hard about the Ukraine and realistically about itself.

The EU didn’t want to force Yanukovych out of power, nor encourage the Maidan movement to force him out of power, because they knew that Russia would react as Russia has in fact reacted.

And the EU knew this about themselves: They were not prepared to do a damn thing about a Russian invasion.

So the EU made a cynical, self-serving decision to not encourage or support the Maidan movement, because they knew they would not be doing anything down the road to support the Maidan movement when the movement actually needed support.

This was an unpopular decision, and it makes them seem cowardly and weak… but it did have the benefit of comporting with reality.

The EU was clear-minded enough and had an honest enough appraisal of its interests and capabilities to make the honest, accurate assessment that they would do nothing in Putin but offer him diplomatic protests were he to invade Ukraine.

And the EU crafted its own policy response based on that accurate, honest appraisal of its own weakness and cowardice.

You can call them cowards, but you cannot call them self-deluded fools.

At least they understood themselves.

April 22, 2014

A “Western colony for gays and paedophiles” versus “a superpower empire that was not conquered by anybody”

David Blair compares the two revolutionary movements in Kiev and in Donetsk:

They are bitter enemies, but they run revolutions in much the same way. Here in the “Donetsk People’s Republic” – as pro-Russian demonstrators like to call this part of eastern Ukraine – the protests look much the same as did in Kiev during the February Revolution.

Once again, everything happens around occupied government buildings, where you find barricades piled high with tyres, passionate speakers and vitriolic propaganda, all surrounded by masked men with clubs and iron bars. The pro-Russian protesters of Donetsk took up their cause in bitter opposition to the Maidan revolutionaries of Kiev, but their methods are pretty much identical.

Earlier today, I spent some time behind the barricades of what was once the administrative headquarters of Donetsk region. This 11-storey building is now the seat of power for the “Donetsk People’s Republic”, which plans to hold a referendum on whether to join Russia by May 11. A triple rampart made from tyres laced with barbed wire now protects the building, manned by sentries in miners’ helmets and black balaclavas.

From a wooden stage in front of the building, a constant relay of speakers calls down fury and vituperation on the new government in Kiev and their supposed masters in America and Europe. There is an epic imagination to the crudeness of the propaganda.

My favourite poster shows a crying baby above a picture of Adolf Hitler and an assortment of drag queens. “Where will your baby live?” asks the caption. “In a Western colony for gays and paedophiles? Or in a superpower empire that was not conquered by anybody?” The latter sentence is accompanied by a picture of a jubilant infant raising both tiny fists in triumph.

April 16, 2014

Russia’s long and brutal relationship with Crimea

In History Today, Alexander Lee talks about the historical attitude of Russia toward the Crimean peninsula and some of the terrible things it has done to gain and retain control over the region:

… Russia’s claim to Crimea is based on its desire for territorial aggrandizement and – more importantly – on history. As Putin and Akysonov are keenly aware, Crimea’s ties to Russia stretch back well back into the early modern period. After a series of inconclusive incursions in the seventeenth century, Russia succeeded in breaking the Ottoman Empire’s hold over Crimea with the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (1774), before formally annexing the peninsula in 1784. It immediately became a key factor in Russia’s emergence as a world power. Offering a number of natural warm-water harbours, it gave access to Black Sea trade routes, and a tremendous advantage in the struggle for the Caucasus. Once gained, it was not a prize to be willingly surrendered, and the ‘Russianness’ of Crimea quickly became a cornerstone of the tsars’ political imagination. When a spurious dispute over custody of Christian sites in the Holy Land escalated into a battle for the crumbling remnants of the Ottoman Empire in 1853, Russia fought hard to retain its hold over a territory that allowed it to threaten both Constantinople and the Franco-British position in the Mediterranean. Almost a century later, Crimea was the site of some of the bitterest fighting of the Second World War. Recognising its military and economic importance, the Nazis launched a brutal attempt to capture the peninsula as a site for German resettlement and as a bridge into southern Russia. And when it was eventually retaken in 1944, the reconstruction of Sevastopol – which had been almost completely destroyed during a long and bloody siege – acquired tremendous symbolic value precisely because of the political and historical importance of the region. Even after being integrated into the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic and – later – acknowledged as part of an independent Ukraine after the fall of the USSR, Crimea’s allure was so powerful that the new Ukrainian President, Leonid Kraychuk, claimed that Russia’s attempts to assert indirect control of the peninsula betrayed the lingering force of an ‘imperial disease’.

[…]

The non-Russian population of Crimea was to suffer further even worse under the Soviet Union, and between 1921 and 1945, two broad phases of persecution devastated their position in the peninsula. The first was dominated by the fearsome effects of Stalinist economic policy. In keeping with the centralised aims of the First Five-Year Plan (1928-32), Crimean agricultural production was collectivised, and reoriented away from traditional crops such as grain. On top of this, bungling administrators imposed impossibly high requisition quotas. The result was catastrophic. In 1932, a man-made famine swept through the peninsula. Although agronomists had warned their political masters of the danger from the very beginning, the Moscow leadership did nothing to relieve the situation. Indeed, quite the reverse. As starvation began to take hold, Stalin not only prosecuted those who attempted to collect left-over grain from the few remaining collectivised farms producing grain, but also hermetically sealed regions afflicted by shortages. He was using the famine to cleanse an ethnically diverse population. A true genocide, the Holodmor (‘extermination by hunger’) – as this artificial famine is known – killed as many as 7.5 million Ukrainians, including tens of thousands of Crimeans. And when it finally abated, Stalin took the opportunity to fill the peninsula with Russians, such that by 1937, they accounted for 47.7% of the population, compared to the Tatars’ 20.7%.

The second phase – covering the period between 1941 and 1945 – compounded the terrible effects of the Holodmor. On its own, the appalling casualties caused by the savage battle for Crimea would have decimated the peninsula. Some 170,000 Red Army troops were lost in the struggle, and the civilian population suffered in equal proportion. But after the Soviet Union regained control, the region was subjected to a fresh wave of horror. Accusing the Tatars of having collaborated with the Nazis during the occupation, Stalin had the entire population deported to Central Asia on 18 May 1944. The following month, the same fate was meted out to other minorities, including Greeks and Armenians. Almost half of those subject to deportation died en route to their destination, and even after they were rehabilitated under Leonid Brezhnev, the Tatars were prohibited from returning to Crimea. Their place was taken mostly by ethnic Russians, who by 1959 accounted for 71.4% of the population, and – to a lesser extent – Ukrainians.