If it is possible to kowtow to a sacred cow, that is exactly what Boris Johnson did on leaving St Thomas’ Hospital after he had been treated there for Covid-19. The NHS, he said, was “Britain’s greatest national asset”, as if, had he fallen ill in any country other than Britain, he would not have been treated so well or simply left to die.

This was an unintended insult to the doctors and nurses of other countries, as if in their benighted lands without the NHS they did not work with skill or devotion. The NHS is neither necessary nor sufficient for medical and nursing staff to show devotion. The parents of a well-taught schoolchild do not thank the Ministry of Education.

No doubt the prime minister’s praise of the NHS was politically shrewd — one casts no doubt on the perfection of the Koran in Mecca — but in the long run such praise does no service to the nation, which at some time or other ought to face up to the fact that its healthcare system is at best mediocre by comparison with that of other countries at a similar level of economic development, and that being ill and seeking treatment is a more unpleasant experience in Britain than in it is many civilised countries.

Untold numbers of people receive excellent care under the NHS. One must neither exaggerate nor catastrophise. But there is another side to the coin as well, and it is surely not a coincidence that no one in Europe would choose Britain as their country of medical care, rather the reverse. If a German were to say, “For God’s sake, get me to the NHS!”, a psychiatrist would be called.

Theodore Dalrymple, “Empire of conformists”, The Critic, 2020-04-29.

August 29, 2020

August 24, 2020

Theodore Dalrymple reviews White Fragility by Robin DiAngelo and How to Be an Antiracist by Ibram X. Kendi

The two books share many characteristics, says the good doctor (in his “Anthony Daniels” guise), and the most noteworthy is a shared hectoring tone:

DiAngelo’s book displays a curious admixture of influences: the Chinese Cultural Revolution, Jimmy Swaggart, Freudian psychoanalysis, and Uriah Heep, the four of them being present in approximately equal proportion.

DiAngelo has apparently made a career of anti-racist struggle sessions in which ordinary employees of various organizations must confess publicly to their racism however hidden it might be, as university professors, primary school teachers, doctors working in slums, etc., had once in China to confess to bourgeois propensities and counter-revolutionary ideas. They may never have uttered a racist sentiment, they may never have been rude to a person of another race, let alone violent towards one, they may have friends of other races or even be married to a person of another race, but they carry racism deep within them like Original Sin, with this difference: there can be no redemption from it even after having read DiAngelo’s book and attended her struggle sessions. Personally, I should not be at all surprised if the end result of all her efforts, at least among the men she has “trained” (which is to say tried to indoctrinate), was to have acted as a recruitment officer for the Ku Klux Klan.

After thirty years of constant work of supposedly anti-racist training, she confesses — like the tearful Jimmy Swaggart — to being still guilty of racism herself, promising to reform, although reform is ex hypothesi impossible because racism is in her society’s DNA, as it were. One is reminded of the type of psychoanalysis which after thirty years of hourly sessions four times a week fails to get to the root of the analysand’s problem, let alone solve it, because it doesn’t even know what the problem is. But failure is also an opportunity, because, like psychoanalysis, the more anti-racist training fails, the more it is needed. DiAngelo, all credit to her, has found an economic niche for herself for the rest of her life. One has a sneaking admiration for such entrepreneurs. They are the asset-strippers of the soul.

As for Uriah Heep, DiAngelo has obviously heard, read, marked, learned, and inwardly digested (as my teachers used to demand of me) David Copperfield. Her oleaginous approach to all “people of color,” as she coyly calls them, makes Uriah Heep seem positively blunt and straight-talking. DiAngelo regards all nonwhite people, ex officio, as being incapable of exaggeration or unjustified self-pity, let alone of lying. As well as being sycophantic, this is, to coin a word, racist, for one of the most important manifestations of free will, and therefore of humanity itself, is the capacity to lie. In effect, then, she regards “people of color” as infra-human truth-uttering mechanisms: they speak, therefore what they say is true. No critical faculties need be applied to what they say.

[…]

DiAngelo is a tremendous moral narcissist. This is shown by her use of the term “people of color.” Until page 31, I thought that it meant black, but on that page I learned that it meant non-white. She shows no interest in the question of whether the Japanese, Chinese, Indians, Burmese, Vietnamese, Cambodians, Austronesians, Amerindians, and Africans, et al., would all be delighted to be put in the same category, let alone interest in their many cultures. On page 33, we read:

White supremacy is more than the idea that whites are superior to people of color; it is the deeper premise that supports the idea — the definition of whites as the norm or standard of human, and people of color as a deviation from that norm.

Lumping non-white people together as “people of color” is precisely an instance of what she criticizes: this is what happens when moral rhetoric far outruns intelligence.

August 18, 2020

QotD: Stigma

Anthropologists used to divide societies into shame and guilt categories. The former depended on people’s public face to keep them in order, the latter on people’s internal sense of right and wrong. No doubt no pure forms of either exist in reality, though in my darker moments I sometimes wonder whether we have succeeded in creating a new type of society, one in which neither shame nor guilt are very much in evidence.

But in fact there is almost a law of conservation of stigma that operates in human societies, such that if it does not attach to one thing, it will attach to another. No doubt there is more stigma in shame societies than in guilt societies, but even in the latter everyone, except perhaps the most psychopathic of psychopaths, is afraid of being shown up in some respect or another.

Stigma begins early in life and children are much guided or influenced in their conduct by the fear of it. A teacher told me the following story. A child of about seven or eight came crying to her one day because another child had called him names.

“What did he say?” she asked.

“He called me a virgin.”

“What is a virgin?” asked the teacher,

“I don’t know,” said the boy. “But I know it’s something horrible.”

Stigma is a kind of shorthand to indicate what we detest. Anyone who pretends that he never stigmatises is probably lying, or perhaps I should say not telling the truth, since not every untruth that emerges from the human mouth is a lie. There are people who can contradict themselves without disbelieving in the law of non-contradiction, and therefore people who can genuinely despise people who pass moral judgment on others.

What would living completely without stigma and stigmatisation mean? Surely that there was nothing that we or anyone else could do to make people think badly of us. One of the reasons — I don’t say the only one — that I don’t steal is that I don’t want to be stigmatised as a thief. One sin doesn’t define a person’s character, however, so that when we stigmatise we must be careful to be just and proportionate. If we called everyone a liar who had told a lie, then we should all be liars (quite apart from the fact that it is sometimes virtuous to tell a lie). We call a liar someone who habitually lies, so that untruthfulness is a central part of his character.

Stigma is one of those many things that is neither good nor bad in itself, and depends for its social beneficence or maleficence on what it attaches to and how strongly. In the company of rogues or scoundrels, one can be stigmatised for honesty. Many a cruel act has been performed to avoid the stigma of being too cowardly to be cruel.

Theodore Dalrymple, “The Situational Nature of Scorn and Stigma”, New English Review, 2020-04-28.

June 26, 2020

QotD: “The freedom to tell lies is one of the most basic freedoms of all”

It was clear to me from the questions that followed that the children had very little notion of what freedom actually was or what it entailed. For example, could it be right to allow climate-deniers to spread their falsehood and lies? The question begs many questions, of course: it assumes that it is beyond reasonable doubt that the globe is warming, that the warming is caused by man’s activities, that the warming is a wholly harmful phenomenon and that there is only one possible solution to it. I am insufficiently knowledgeable to pronounce on these questions and have heard eminent people whom I respect and whose integrity I have no grounds for doubting argue for very different conclusions.

But even if there were answers to these questions that were a good deal more certainly true than any answers that we possess today, it still would not be right to silence doubters and deniers: for error and even malice are the price of freedom. In the realm of intellectual freedom it is not truth that sets you free, but error, or rather the permissibility of error. And the freedom to tell lies is one of the most basic freedoms of all. There can be no freedom without it.

Well, the audience was only young and perhaps this was strong meat for their immature digestions rendered sensitive by a constant diet of modern pieties, as the young these days are said to be more likely to develop allergies because of the sterility and cleanliness of modern homes and ways of life (what they need is more dirt and early contact with potential pathogens). But soon they would be going off to university, where it was likely that they would encounter an even narrower and powerfully self-reinforcing view of the world. The pressure to conform would add to the natural self-righteousness of youth, which is often mistaken for idealism, and their impulse to censor in the name of their own irreproachable virtue would be strengthened and entrenched.

The long-term prospects for freedom of speech, then, are not altogether rosy. Those who value it are less vehement in their defence of it than are the self-righteous in their assault on it.

Anthony Daniels, “Free Speech’s Emboldened Enemies”, Quadrant, 2018-03-10.

June 17, 2020

May 29, 2020

Theodore Dalrymple reviews 100 Principles for a New World by Nicolas Hulot

It’s kind of subtle, but I don’t think he’s a fan of the writer or his work:

No opinion is worth expressing that is not also worth contradicting (except, perhaps, this one); nevertheless, clichés have their attraction. They are the teddy-bears of the mind, or, to change the metaphor slightly, the mental lifebuoys we cling to in times of stormy intellectual or political weather. They are the sovereign remedy for thought, which is always a rather painful activity.

“Can’t you stop me thinking, doctor?” asked some of my patients in the prison in which I worked, in the hope of a prescription of pills that would make them feel fuzzy and incapable of coherent mentation. For those who prefer a less drastic or non-pharmacological solution to the discomforts wrought by the contemplation of the world and their part in it, there are pseudo-thoughts with comforting connotations of wisdom, generosity, goodness, kindness, benevolence, etc. They are the kind of people, I suppose, who might think that Kahil Gibran’s kitsch vapourings are profound.

They would no doubt like Nicolas Hulot’s 100 Principles for a New World, published on 7 May in Le Monde. Hulot, an ecological activist, television personality and journalist once specialising in motorcycle racing, was M. Macron’s Minister for the Ecological and Solidary Transition (by their job titles shall ye know them) until he resigned with maximal noise in August 2018, having held the post for 15 months.

I confess that I was shocked by the banality of the mind, or alternatively the cynicism, of the person who could have written and published a manifesto such as Hulot’s – to say nothing of the astonishing lack of judgment of a respectable newspaper in publishing it. The last time that I was shocked so much by a politician’s vacuity was when I heard another Nicolas, Sarkozy this time, give a speech in person. He was like a dried pea rattling about and shaken in a tin box. He jumped around the stage making a passionate verbal noise, but nothing he said had any discernible tether to anything concrete. Within seconds of his finishing, no one could have given any account of what he had said. Is mastery of this kind of meaningless verbalisation, eloquently empty and passionately delivered, the key to political success? And if so what does it say of us, the citizens of democracies?

But to return to Hulot and his Hundred Principles. They each started “The time has come to…” or “The time has come for…”, followed by a cliché, a truism, or a banal falsehood, all expressed with a self-satisfaction that would have made Mr Pecksniff seem like a self-doubter.

February 15, 2020

Theodore Dalrymple on the death penalty

From the New English Review:

“Tombstone Courthouse State Historic Park” by August Rode is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

I happened to read a book published in 1965, the year Britain legislated to end the death penalty, titled Murder Followed by Suicide, by the distinguished criminologist, D.J. West. For forty years up to that date, about a third of homicides had been followed by the suicide of those who committed them.

Most people who committed homicide followed by suicide were highly disturbed psychologically, if not outright mad. For example, in killing their families they imagined that they were saving them from a worse fate. They were not the kind of people who would be deterred by anything, including the death penalty.

Here was a natural experiment. I hypothesized that if the death penalty acted as a deterrent, the homicide rate would increase but the proportion of homicide followed by suicide, which in absolute numbers would remain more or less the same, would decrease. My friend, the criminologist David Fraser, looked at the actual figures and found that this was indeed the case. Some sane people who might otherwise be inclined to kill managed to control themselves knowing that they might be executed if they did.

For the death penalty to deter, it was not necessary for it to be applied in every case. Although the death penalty for murder was mandatory in Britain, it was commuted in nine cases out of ten. All that was necessary for it to deter was that execution was a real possibility. We shall never know whether the death penalty would have deterred even more if it had been applied more rigorously.

Does its deterrent effect, then, establish the case for the death penalty, at least in Britain? No, for two reasons. First, effectiveness of a punishment is not a sufficient justification for it. For example, it might well be that the death penalty would deter people from parking in the wrong place, but we would not therefore advocate it. Second, the fact is that in all jurisdictions, no matter how scrupulously fair they try to be, errors are sometime made, and innocent people have been put to death. This seems to me the strongest, and perhaps decisive, argument against the death penalty.

Against this might be urged the undoubted fact that some convicted murderers who have been spared death have gone on to kill again, and this will continue to be so. Victims of those who murder a second time are probably more numerous than those executed in error. Therefore, utilitarians might argue, even if mistakes are sometimes made, that the death penalty overall would save lives. (Let us disregard the fact that those murderers who go on to murder a second time would not necessarily have been executed after their first murder, for nowhere are all murderers executed.)

The argument holds only if utilitarianism is accepted as a true ground of ethics. But few of us would accept that it is. It might be that hanging the wrong person after the commission of a terrible crime would have a better social outcome than hanging no one at all, provided only that it was never publicly known that the wrong person had been hanged: but we would still be horrified at the prospect. Moreover, in practice, the execution of the innocent, once it is known, serves disproportionately to undermine faith in the justice system. And surely it is true that for the state to kill an innocent man is peculiarly horrific.

February 4, 2020

QotD: Brutalist “sincerity”

Apologists and defenders of brutalism often use astonishing arguments. Here, for example, is what an Australian wrote recently:

Unrefined concrete was an honest expression of [brutalist architects’] intentions, while plain forms and exposed structures were similarly sincere.

This is like saying that the Gulag was an honest expression of Stalin’s intentions. Sincerity of intentions is not a virtue irrespective of what those intentions are, and as a matter of fact those of the inspirer and founder of brutalism were clearly evil, as the slightest acquaintance with his writings will convince anyone of minimal decency. And what exactly is “sincerity of form and exposed structures”? Is it meant to imply that anything other than brutalism is insincere?

The same article continues:

Beyond their architectural function, Brutalist buildings serve other uses. Skateboarders, graffiti artists and parkour practitioners, for example, have all used Brutalism’s concrete surfaces in innovative ways.

Dear God! I have nothing against playgrounds — they are socially commendable, especially for children — but to regard the urban fabric as properly an extended playground is surely to infantilize the population. As for graffiti artists, to regard the extension of their “canvas” to large public buildings is an abject surrender to vandalism. No one, I presume, would say of a wall, “And in addition it would make an excellent place for a firing squad.”

Theodore Dalrymple, “The Brutalist Strain”, Taki’s Magazine, 2019-11-02.

January 23, 2020

January 7, 2020

QotD: The cult of Le Corbusier

What accounts for the survival of this cold current of architecture that has done so much to disenchant the urban world — the original modernism having been succeeded by different styles, but all of them just as lizard-eyed? According to Curl, the profession of architecture has become a cult. It is worth quoting him in extenso:

A dangerous cult may be defined as a kind of false religion, adoption of a system of belief based on mere assertions with no factual foundations, or as excessive, almost idolatrous, admiration for a person, persons, an idea, or even a fad. The adulation accorded to Le Corbusier, accorded almost the status of a deity in architectural circles, is just one example. It has certain characteristics which may be summarized as follows: it is destructive; it isolates its believers; it claims superior knowledge and morality; it demands subservience, conformity, and obedience; it is adept at brainwashing; it imposes its own assertions as dogma, and will not countenance any dissent; it is self-referential; and it invents its own arcane language, incomprehensible to outsiders.

Anyone who thinks this is an exaggeration has not read much Le Corbusier. (His writing is as bad as his architecture, and bears out precisely what Curl says.) Nor is it difficult to find in the architectural press examples of cultish writing that is impenetrable and arcane, devoid of denotation but with plenty of connotation. Here, for example, is Owen Hatherley, writing about an exhibition of Le Corbusier’s work at London’s Barbican Centre (itself a fine example of architectural barbarism). According to Hatherley, Le Corbusier was:

the architect who transformed buildings for communal life from mere filing cabinets into structures of raw, practically sexual physicality, then forced these bulging, anthropomorphic forms into rigid, disciplined grids. This might be the work of the “Swiss psychotic” at his fiercest, but the exhibition’s setting, the Barbican — with its bristly concrete columns and bullhorn profiles, its walkways and units — proves that even its derivatives can become places rich with perversity and intrigue, without a pissed-in lift [elevator] or a loitering youth in sight. … [T]hese collisions of collectivity and carnality have no obvious successors today.

Theodore Dalrymple, “Crimes in Concrete”, First Things, 2019-06.

November 10, 2019

Theodore Dalrymple on today’s doomsday cults

The recent antics of Extinction Rebellion activists in London encouraged Theodore Dalrymple to do a bit of reading on the psychology of such cults and their followers:

Man is the only creature, as far as we know, that enjoys the contemplation of its own disappearance from the face of the earth. We find the prospect of our annihilation by disease, famine, war, asteroid, or climate change deeply satisfying. We feel, somehow, that we deserve it and that the world would be a better planet without us.

When to this strange source of satisfaction is conjoined a license to behave badly in the name of salvation from earthly perdition, we can expect a mass movement that approaches insanity. So it is with the Extinction Rebellion, whose fanatical members have brought chaos to London recently by blocking streets, occupying crossroads, gluing themselves to public buildings and railings, and standing atop underground trains, to the fury of thousands of rush-hour commuters who don’t want to save the world but only get to work.

In order to try to understand their state of mind, I recently read a book by three psychologists, Leon Festinger, Henry W. Riecken, and Stanley Schachter, first published in 1956, called When Prophecy Fails. It recounts the reaction of a small doomsday sect in America founded by a housewife, who believed that most of North America was soon to be inundated by a great flood. When this failed to happen on the predicted date, members did not immediately conclude that the absurd grounds upon which their belief was based were false, but became even more convinced of their truth. When there is a contradiction between what we want to be the case and what is the case, our desire to believe often triumphs, at least for a time.

The beginning of the book gives a brief and selective history of sects that have predicted Man’s total annihilation in the near future, among them that of the Millerites in the 1840s in the United States. Reading the account of this sect, I could not help but think of the Extinction Rebellion that is now gripping London, to the growing fury of the rest of the population.

October 9, 2019

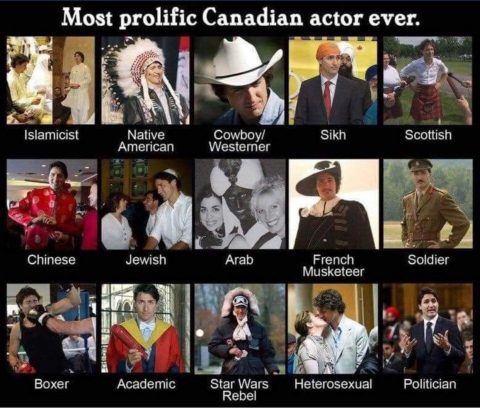

Theodore Dalrymple on Justin Trudeau and David Cameron

He doesn’t hate either of them, he just thinks they are either fools or knaves. As the Instapundit often says, it might be time to “embrace the healing power of ‘and'”:

No doubt it is the mark of bad character to rejoice, as I do, in the spectacle of a man being hoist with his own petard, and as the Canadian Prime Minster, Justin Trudeau, has recently been hoist. And while I am at it, I confess also that, though I know that there is no art to find a mind’s construction in the face, I cannot help also but judge people, at least to an extent, by their physiognomy. And the fact is that Mr Trudeau has a face as characterless as that of the former British Prime Minister, David Cameron. They are of the same ilk. You look at them and think “What nullities!” The main character discernible in their faces is lack of character.

David Cameron’s official portrait from the 10 Downing Street website, 3 August 2010.

Open Government Licensed image via Wikimedia Commons.It is not their fault, perhaps; besides which I, or you, might be mistaken in our assessment of them and actually they have backbones (or what my teachers use to call moral fibre) of enormous strength. In any case, there are worse things to be, especially in the field of politics, than a nullity: an evil monster, for example, would be far worse, and no one could seriously claim that either of Messrs Trudeau and Cameron are, or were, evil monsters, however little they inspire admiration.

No one, then, could accuse me of partiality for Mr Trudeau, and the abjectness of his apology for his behaviour when he was a very young man did nothing to increase my liking for him. But it seems to me that sins as a young man were venial at worst, a callow disregard of the sensibilities of others which I common in youth. I very much doubt that he was a deep-dyed racist in any dangerous way, more a silly boy having a bit of fun.

There is a serious side to this imbroglio, of course. If the political leader of an important country can be overthrown or not re-elected on so relatively trivial a ground, while at the same town no one cares in the least about his shallow but dangerous moral posturing and obviously weak-minded pandering to the ayatollahs of an absurd and ill-founded political morality, then a new nadir of decadence and cowardice has been reached. It is a difficult question of moral philosophy as to whether it would be worse if Mr Trudeau actually believed his own political correctness or merely made use of it as a means to power. If the former, he is a fool; if the latter a knave. I leave it to others to decide which is better in a politician, or indeed in any other human being, foolishness or a knavery.

Political correctness is dangerous because when fools or knaves get into power, they may try to implement its dictates. And since many people are much more concerned to appear good than to do good, and since they are unlikely to suffer the consequences of their own actions (except when hoist on their own petard), the implementation may continue for a long time after the negative effects of its dictates have become clear. When implemented, those dictates create a clientele dependent upon their continuation, which turns any attempt to undo the harm into a nasty social conflict.

July 19, 2019

June 15, 2019

QotD: The early Bauhaus

The ideas of the modernists were generally expressed in the imperative mood and were frequently of a pseudo-mystical nature. Professor Curl’s description of some of the practices prevalent in the early Bauhaus make for hilarity; cranks are always a source of fun. In the early days, the modernists of the Bauhaus tended to a form of health mysticism involving vegetarianism, garlic paste, and regular enemas. Far more important, however, was their early and inherent attraction to totalitarianism. As the author points out, Gropius and Miës van der Rohe had no objection to Nazism other than that the Nazis failed to commission work from them. Gropius was an opportunistic anti-Semitic snob who espoused communism until it was no longer convenient for his career. Miës sucked up to the Nazis as much as he was able. The fact that both of them emigrated from Germany has done much to obscure their accommodation with the Nazis and even allowed the modernists to pose as anti-Nazi — though the most important proponent of modernism in America, Philip Johnson, had for some years been a rank Nazi in more than merely nominal terms. Moreover, as Professor Curl points out, the Nazi aesthetic, like the communist, had much in common with modernism.

Theodore Dalrymple, “Crimes in Concrete”, First Things, 2019-06.

May 15, 2019

Modern architecture as a generations-long art crime spree

Theodore Dalrymple is clearly quite a fan of Making Dystopia: The Strange Rise and Survival of Architectural Barbarism by James Stevens Curl, as this is at least the third review of the book I’ve seen by him (and you can probably tell I agree with much of his viewpoint that I’m blogging it yet again…)

In a recent debate in Prospect magazine on the question of whether modern architecture has ruined British towns and cities, Professor James Stevens Curl, one of Britain’s most distinguished architectural historians, wrote as his opening salvo:

Visitors to these islands who have eyes to see will observe that there is hardly a town or city that has not had its streets — and skyline — wrecked by insensitive, crude, post-1945 additions which ignore established geometries, urban grain, scale, materials, and emphases.

This is so self-evidently true that I find it hard to understand how anyone could deny it, but modern architects and hangers-on such as architectural journalists do deny it, like war criminals who, for obvious reasons, continue to deny their crimes in the face of overwhelming evidence.

This is true not only of Britain but of many, perhaps most, other countries that have or had any towns or cities to ruin. Anyone who rides into the center of Paris from Charles de Gaulle Airport, for example, will be appalled at the modernist visual hell that scours his eyes as he goes.

Nor is this visual hell the consequence of the need to build cheaply. Where money is no object, contemporary architects, like the sleep of reason in Goya’s etching, bring forth monsters. The Tour Montparnasse (said to be the most hated building in Paris), the Centre Pompidou, the Opéra Bastille, the Musée du quai Branly, the new Philharmonie, do not owe their preternatural ugliness to lack of funds, but rather to the incapacity, one might say the ferocious unwillingness, of architects to build anything beautiful, and to their determination to leave their mark on the city as a dog leaves its mark on a tree.

Professor Curl’s magnum opus is both scholarly and polemical. He has been observing the onward march of modernism and its effects for sixty years and is justifiably outraged by it. British architects have managed to reverse the terms of the anarchist Bakunin’s dictum that the urge to destroy is also a creative urge: Their urge to create is also a destructive urge. I could give many concrete examples (no pun intended).

Curl knows that he is arguing not against an aesthetic, but against an ironclad ideology. The architectural Leninists have been determined so to indoctrinate the public that they hope and expect a generation will grow up knowing nothing but modernism, and therefore will be unable to judge it. (All judgment is comparative, as Doctor Johnson said.) In Paris recently, I saw an advertisement on the Métro (a few days before the fire in Notre-Dame) to the effect that Paris would not be Paris without the Centre Pompidou — which, of course, has a good claim to be the ugliest building in the world. In the face of such an advertisement promoted by the cultural elite, what ordinary person would dare demur?

Centre Georges-Pompidou (no, this isn’t an under construction image … it’s from 2017 and the construction was technically complete in 1977)

Gerd Eichmann photo via Wikimedia Commons.

Could anyone imagine a worldwide outpouring of genuine and heartfelt grief, such as that which greeted the burning of Notre-Dame de Paris, if any building of the last seventy years burnt down? Indeed, the destruction of many would be a cause almost for rejoicing. Modernist buildings will never age as Notre-Dame aged; they will merely deteriorate, and usually do deteriorate even before completion.