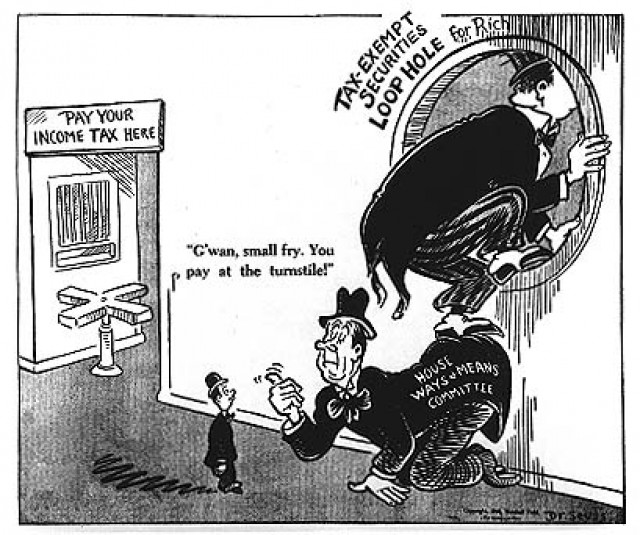

Darton Williams posted this on Google+:

This is a WWII-era political cartoon by Theodor Geisel (AKA Dr. Seuss). Why is it still so relevant? Has anything actually changed for the better?

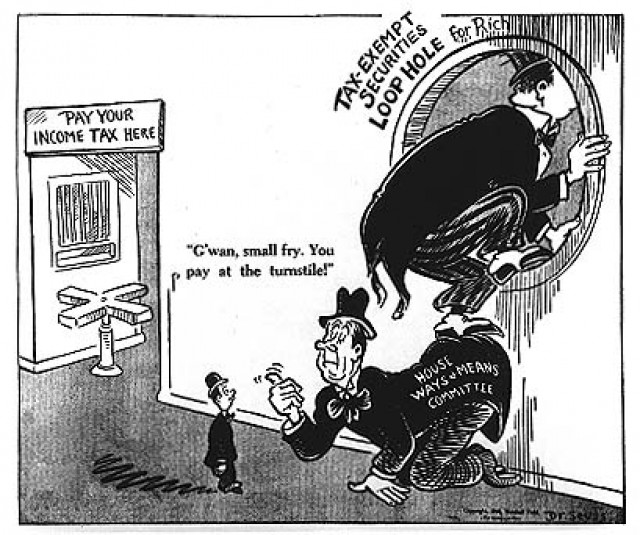

Darton Williams posted this on Google+:

This is a WWII-era political cartoon by Theodor Geisel (AKA Dr. Seuss). Why is it still so relevant? Has anything actually changed for the better?

In Maclean’s, Michael Friscolanti and Kate Lunau round-up the tales of cold weather misery from across the country:

From coast to coast, Canadians have done everything they can to survive this winter of discontent. The Old Man arrived early and never let go, unleashing a harsh brew of bone-chilling mornings, wicked gusts of wind and collective pleas for mercy. We learned a new scientific term — “polar vortex” — and felt it, firsthand, on our fingertips. It’s been so bleak that, as of early March, 92.2 per cent of the Great Lakes were covered in ice, the most since 1979. On March 1, Regina broke a 130-year-old record for that day’s temperature: -36° C, with a wind chill of -53° C. In Kenora, Ont., where all-time winter lows have wreaked havoc on its maze of underground pipes, the city is in the midst of a two-week boil-water advisory.

In Toronto, where the mercury also nosedived to the lowest point in two decades, the city surpassed its record for consecutive days with at least one centimetre of snow on the ground: 89, as of March 7, and counting. No town, though, amassed more white stuff than Stephenville, N.L. (population 7,800). The winter isn’t even over, and the seaside community has already been hammered with more than two metres (the same height, for the record, as Michael Jordan.) “In December, it snowed 26 days,” says Mayor Tom O’Brien. “The snow kept coming and coming. It wasn’t one big wallop.”

[…]

GDP fell by 0.5 per cent in December, a dip triggered almost entirely by the pre-Christmas ice storms that rocked Ontario, Quebec and Atlantic Canada. Canadian retail stores reported their biggest one-month drop in a year. And in a spat that garnered significant headlines, the country’s two main railways — CP and CN — blamed “the harshest winter in 60 years” for their inability to ship millions of tonnes of grain sitting in bins across the Prairies.

Economists are fairly confident the gloomy numbers will eventually pass, like winter itself. By the second quarter, they say, the season’s losses will be almost entirely recouped, with the North American economy picking up significant steam on its road to recovery. But that rosy economic outlook glosses over a much frostier reality: This winter for the ages will cost Canadian cities untold millions in extra snow-clearing, pothole maintenance and other infrastructure repair bills that have yet to arrive. In this era of climate change — when scientists expect severe bouts of weather to become the rule rather than the exception — the past few months have provided a disturbing glimpse of the overwhelming costs to come.

[…]

In Toronto alone, the ice storm cost the public purse more than $100 million; throw in Hamilton and the rest of the GTA, and the liability climbs to $275 million. Point to any Canadian city these days, and it’s hard to find one that won’t be digging deeper into its pockets to pay for this brutal winter.

In Edmonton, potholes are already such an epidemic that the city is teaming up with the University of Alberta engineering department to figure out ways to make roads more robust in chilly conditions. (Last year, the City of Champions paid out a record $464,000 to motorists whose cars were damaged by craters.) In Chatham, Ont., one winter pothole went so deep, it revealed the city’s original yellow brick road. Down the highway in Windsor, councillors were forced to commit an extra $1 million to their snow-removal budget — by early January. And in Niagara Falls, the unbearable cold triggered 42 water-main breaks by the end of February, more than half the total of the entire year before.

Let’s be clear: parts of California are doing fantastically well, but other portions of the state are suffering disproportionally. Here are a few suggested legislative fixes to redress the inequalities of life faced by too many disadvantaged people in the state:

2. The Undocumented Immigrant Equity Act

The “I am Juan too Act” would assess all California communities by U.S. Census data to ascertain average per-household income levels as well as diversity percentages. Those counties assessed on average in the top 10% bracket of the state’s per-household income level, and which do not reflect the general ethnic make-up of the state, would be required to provide low-income housing for undocumented immigrants, who by 2020 would by law make up not less than 20% of such targeted communities’ general populations.

There are dozens of empty miles, for example, along the 280 freeway corridor from Palo Alto to Burlingame — an ideal place for high-density, low-income housing, served by high-speed rail. Aim: One, to achieve economic parity for undocumented immigrants by allowing them affordable housing in affluent areas where jobs are plentiful, wages are high, and opportunities exist for mentorships; and, two, to ensure cultural diversity among the non-diverse host community, bringing it into compliance with the state’s ethnic profile.

[…]

4. The Silicon Valley Transparency and Fair Jobs Act

This “Google Good Citizen Act” would set up a regional board to monitor commerce in the San Francisco, San Mateo, and Santa Clara tri-county area. The state regulatory commission would monitor offshore investment, outsourcing, and unionization. All commercial entities, with over 100 employees, would be in violation and face state fines if: 1) the number of a firm’s employees overseas accounted for 10% or more of the workforce currently employed within the tri-county Silicon Valley area; 2) more than 1% of the current capitalization of a Silicon Valley company were deposited in banks outside the United States; and 3) more than 50% of a tri-county company’s workforce were non-union. Aim: To ensure progressive Silicon Valley commercial businesses are caring progressive state citizens.

5. The California Firearms Safety Act

The “No Guns for Grandees Act” would forbid private security details to be armed with handguns or semi-automatic long guns. It would allow private security personnel to be armed only with paintball, BB or pellet guns. Aim: To prevent unnecessary armed deterrence by private security units in the hire of the affluent.

6. The Fair Housing Adjustment Act

The “Everywhere an Atherton Act” would tax all private residential square footage in excess of 1800 square feet at four times the current per square foot assessment. Aim: It would ensure state resources are equally distributed and not inordinately siphoned off to a small minority of the state population. Would encourage existing large homes to downsize through reverse remodeling.

James Delingpole on the remarkable community of interest between charitable organizations (partly funded by governments) and the government agencies they lobby:

“To compel a man to furnish contributions of money for the propagation of opinions which he disbelieves and abhors is sinful and tyrannical”. Thomas Jefferson, 1779.

One of the curses of modern life is the plethora of “charitable” lobbying groups demanding that the government take more regulatory action in areas where most of us believe the state has no business interfering.

Almost every day you read in the papers that some apparently grassroots movement, supposedly speaking for all of us, thinks more should be done to stop us drinking, smoking, eating sugar or salt, make us less sexist, force us to spend more on foreign aid or environmental issues. But if that wasn’t annoying enough, here’s the worst thing of all: we’re paying for these unrepresentative, mostly left-leaning lobby groups with our taxes.

This is the message of Chris Snowdon’s report for the Institute of Economic Affairs, The Sock Doctrine [PDF] — the third in his trilogy of broadsides against the lavishly state-funded “fake charities” industry. By 2007, he noted, a quarter of the UK’s 170,000 charities were receiving money from the state and approximately 27,000 received at least 75 per cent of their income from the state. If you share these charities’ predominantly liberal-Left-leaning aims you probably won’t mind so much. But if you don’t, you might be inclined to believe, as Fraser Nelson argued in these pages last year, that “Britain’s charities are nurturing a colourful, talented and efficient anti-Tory alliance.”

But, of course, there are opposing charitable organizations equally dependent on government funding and spending disproportional time and effort lobbying for their pet causes?

Well the problem is that they’re almost non-existent. The reason for this was identified in 1985 by US researchers James T. Bennett and Thomas J. DiLorenzo:

“Virtually without exception, the recipients of government grants and contracts advocate greater governmental control over and intervention in the private sector, greater limitations on rights of private property, more planning by government, income redistribution, and political rather than private decision making. Most of the tax dollars used for political advocacy are obtained by groups that are on the left of the political spectrum.”

Gregg Easterbook is worried that we’re at peak football (NFL football, anyway), and has a few suggestions to fix what he thinks are some of the worst problems facing the game as a whole:

For the NFL:

- Revoke the nonprofit status of league headquarters, and the ability of the league and individual clubs to employ tax-free bonds. A bill before the Senate, from Republican Tom Coburn of Oklahoma, would end these and other sports tax breaks.

- Require disclosure of painkiller use club by club — as anonymous data, with names removed. Painkiller abuse may be football’s next scandal.

- Change law so images of football games played in publicly funded stadia cannot be copyrighted. The effect would be that the NFL would immediately repay all stadium construction subsidies, and never seek a subsidy again. Altering national copyright law seems more promising than trying to ban pro football stadium subsidies state by state, since the handouts originate with a broad mix of state, county and city agencies. (Yes, careful wording of such a law would be required to prevent unintended consequences.)

For the NCAA:

- Graduation rates should be factored into the new FBS playoff ranking system. Not the meaningless “Academic Progress Rate” the NCAA touts precisely because of its meaninglessness — graduation is what matters. News organizations that rank college football should add graduation rates voluntarily, as news organizations have voluntarily agreed to many best-practice standards.

- For FBS players, the year-to-year scholarship — which pressures them to favor football over the library, to ensure the scholarship is renewed — should be replaced with a six-year scholarship. That way once a player’s athletic eligibility has expired, typically after 4.5 years, and once the NFL does not call — 97 percent of FBS players never take an NFL snap — there will be paid-up semesters remaining for him to be a full-time student, repair credits and earn that diploma. Not all will need the extra semesters. But six-year full scholarships would change big-college football from a cynical exercise in using up impressionable young men and throwing them away, into a fair deal: The university gets great football, the players get educations.

- NCAA penalties should follow coaches. If a coach breaks rules at College A then skedaddles to College B, all College A sanctions should follow him. The NFL should agree, voluntarily, that the length of any NCAA penalties follows any coach who skedaddles to the pros. So if Coach A gets out of town just before the posse arrives and imposes a two-year sanction on College B, Coach A should face a two-year sanction from the NFL.

[…]

For football at all levels:

- Eliminate kickoffs, the most concussion-prone down. After a score, the opponent starts on his 25. Basketball eliminated most jump balls; purists cried doom; basketball is just fine.

- Ban the three-point and four-point stance. Because of these stances, most football plays begin with linemen’s heads colliding. No reform reduces helmet-to-helmet contact faster than requiring all players to begin downs with hands off the ground and heads up. Will this make football a sissified sport? That’s what was said of the forward pass.

- Only four- or five-star rated helmets should be permitted. Some of the safest helmets are prohibitively expensive for public high school districts, but the four-star, $149 Rawlings Impulse is not. Only double-sided or Type III (individually fitted) mouth guards should be permitted. Double-sided mouth guards are the most cost-effective way to protect against concussions. Many players won’t wear them because they look geeky. If everyone was wearing them, this would not matter.

A more general reform is needed, too. Football has become too much of a good thing. Tony Dungy told me for The King of Sports, “If I could change one aspect of football, it would be that we need more time away for the game, as players and as a society. Young boys and teens should not be doing football year-round. For society, it’s great that Americans love football. But now with the internet, mock drafts, fantasy leagues and recruiting mania year-round, with colleges and high school playing more games and the NFL talking about an even longer schedule — we need time off, away from the game.” We need less of everything about football.

Emma Elliott Freire explains why she and other Americans living and working in other countries feel like they’re being treated as “toxic citizens”:

The [travel] books tend to emphasize romance and adventure. As an American who is actually living abroad, though, I’ve found that the reality is quite different. My fellow Americans back home sometimes regard me with suspicion, and I feel like my government considers me a “toxic citizen.”

The US is one of two countries in the world that taxes its citizens on the income they earn while living abroad. The other is Eritrea. Every single other country bases its taxation on residency, i.e., you only pay taxes where you live and work.

Americans are required to file an annual tax return with the IRS when they’re abroad — even if they don’t owe any money. They’re also required to file a form called an FBAR to declare their foreign bank accounts. An undeclared account incurs a $10,000 fine.

As you might expect, international tax accountants get a lot of business from Americans. One tax accountant based in Amsterdam told me his American clients take their filings very seriously. “If they get the IRS going after them, they have a real problem,” he says.

His clients are the savvy ones, though. In my experience, many Americans who move abroad are not aware that they need to file. The US government does precious little to inform its citizens of their obligations in this area. Over several years, I’ve been informally asking Americans I meet abroad if they file their US taxes. Most of them told me they don’t. They only file and pay taxes in their country of residency. They assume that’s enough. But, in fact, they have unwittingly become lawbreakers. If they move back to America, they could find themselves in quite a bit of trouble.

The IRS is enforcing new rules passed in 2010, which extend US taxation laws to non-US banks that deal with American citizens. To no great surprise (except perhaps to the legislators themselves), a side-effect of this is that many banks are closing existing accounts and refusing to accept new business from American would-be customers:

The IRS is currently implementing a new law called the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA). Basically, FATCA requires every bank in the entire world to report the account information of its American clients. So every bank in the world is becoming an agent of the US government. It’s still unclear how FATCA can be implemented because in some countries it violates national privacy laws. However, FATCA stipulates that any foreign bank that fails to comply will be subject to a 30 percent withholding tax on its US income.

At the Adam Smith Institute blog, Tim Worstall talks about the way regulatory agencies approach problems:

It’s claimed as one of the great victories for enlightened (sorry) regulation, the way that the EU and US have both banned the incandescent light bulb through bureaucratic action. The ban came about by raising the efficiency standards required: this meant that the traditional bulb could no longer be sold.

The argument in favour of doing things this way was, in public at least, that everyone’s too stupid (or, in a more polite manner, subject to hyperbolic discounting) to realise that the new bulbs will actually save them money in the long term by consuming less electricity. There are also the more cynical in the industry who insist that it’s actually a case of regulatory capture. The light bulb manufacturing companies managing to get us all away from using cheap as spit bulbs and onto something with a decent margin on it.

[…]

This has a number of implications in the larger world as well: for example, it means that bureaucratic regulation on car mileages (like CAFE in the US) is contra-indicated. A simple tax on petrol will drive up average mpg because we’re not all as thick as bricks. Assuming that climate change really is a problem that must be dealt with then a carbon tax is going to do the job. For we’re not all so dim that we cannot work out the utility of using fossil fuels or not given the change in prices.

That is, we don’t need to be regulated into behaviour, we can be influenced into it through the price system. Something that really shouldn’t be all that much of a surprise to us market liberals: for we’re the people who already insist that people do indeed respond to price incentives in markets.

On the one hand, he’s delighted that something he advocated for years finally came to pass. On the other, well, he’s still also in favour of adults being allowed to make decisions on what they put into their bodies (and owning the consequences of their actions), so perhaps we only need the one hand after all.

As a Denver Post columnist from 2004-2011, I spent a considerable amount of time writing pieces advocating for the legalization of pot. So I was happy when the state became one of the first to decriminalize small amounts of “recreational” marijuana. I believe the War on Drugs is a tragically misplaced use of resources; an immoral venture that produces far more suffering than it alleviates. And on a philosophical level, I believe that adults should be permitted to ingest whatever they desire — including, but not limited to, trans-fats, tobacco, cough syrup, colossal-sized sodas, and so on — as long as they live with the consequences.

You know, that old chestnut.

Unrealistic? Maybe. But less so than allowing myself to believe human behavior can/should be endlessly nudged, cajoled and coerced by politicians.

So, naturally, I was curious to see how marijuana sales in Colorado would shake out. According to the Denver Post, there are nearly 40 stores in Colorado licensed to sell “recreational” pot. Medical marijuana has been legal for more than a decade. (And, having spent time covering medical pot “caregivers” — or, rather, barely coherent stoners selling cannabis to other barely coherent stoners, a majority of whom suffer from ailments that an Excedrin could probably alleviate — it will be a relief to see that ruse come to end. I’m not saying marijuana doesn’t possess medicinal uses. I’m saying that most medicinal users are frauds.)

Not surprisingly, pot stores can’t keep up with demand for a hit of recreational tetrahydrocannabinol. Outside of Denver shops, people are waiting for up to five hours to buy some well-taxed and “regulated” cannabis. The pot tourists have also arrived. All this, the Denver Post estimates, will translate into $40 million of additional tax revenue in 2014 — the real reason legalization in Colorado became a reality.

Talk about unintended consequences! Jim Geraghty linked to a disturbing issue for many Americans, but especially for Pennsylvanians: the risk of losing some of their volunteer firefighters due to an Obamacare rule. Ninety-seven percent of Pennsylvania fire departments are at least partially staffed by volunteers … this could be a very serious thing indeed.

Great. Now Obamacare Is Going to Louse Up Your Local Firehouse…

They had to pass the law so you could see what’s in it. Kind of like Pandora’s Box.

With any luck, Obamacare won’t close down your local firehouse, just curtail emergency response activities:

The International Association of Fire Chiefs has asked the Internal Revenue Service, which has partial oversight of the law, to clarify if current IRS treatment of volunteer firefighters as employees means their hose companies or towns must offer health insurance coverage or pay a penalty if they don’t.

The organization representing the fire chiefs has been working on the issue with the IRS and White House for months.

“It could be a huge deal,” said U.S. Rep. Lou Barletta, R-11, Hazleton, who is seeking clarification from the IRS. “In Pennsylvania, 97 percent of fire departments are fully or mostly volunteer firefighters. It’s the fourth highest amount in the country.”

So far, the IRS hasn’t decided what to do.

Efforts to reach spokesmen for the IRS were unsuccessful.

Under the fire chiefs’ organization’s interpretation, the concern goes like this:

The health care reform law, known officially as the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and derisively by Republicans as Obamacare, requires employers with 50 or more full-time employees to offer health insurance. Companies with fewer than 50 employees do not have to offer insurance. Full-time employees are defined as an employee who works 30 or more hours a week.

Such employers who don’t offer health insurance must pay fines.

The requirement is complicated by differing interpretations about the status of volunteer firefighters within the federal government. The Department of Labor, according to the fire chiefs group, classifies most volunteers as non-employees, but the IRS considers all volunteer firefighters and emergency medical personnel to be employees of their departments.

“If the IRS classifies volunteer firefighters and emergency medical personnel as employees in their final rule, fire departments may be unintentionally forced to comply with requirements that could force them to curtail their emergency response activities or close entirely,” the chiefs’ group says on its website.

Megan McArdle is convinced that despite the appeal, any form of guaranteed income is doomed to fail. She provides four strong reasons for this, but I think the strongest reason is sheer mathematical impossibility:

Not a few libertarians have embraced the idea as an alternative to the welfare state. Get rid of all the unemployment insurance and just cut everyone a check once a month. There’s a lot to like about this: It has minimal overhead, because you don’t need to verify eligibility beyond citizenship, and it may reduce some of the terrible incentives that poor people face under the current system.

There are a couple of problems with this, however. The first is that zeroing out our current income security system wouldn’t provide much of a basic income. Total federal spending on income security (welfare, unemployment, etc.) is under $600 billion a year. There are 235 million adults in the U.S. Millions of those are undocumented immigrants, but that still leaves you with a lot of people. Getting rid of all of our spending on welfare and so forth would be enough to give each of those people less than $3,000 a year. For a lot of poor people, that’s considerably less than what they’re getting from the government right now.

The problem is that if you try to bring it up to something a bit more generous, the cost quickly escalates. Cutting everyone a check for $1,000 a month, which most people in that room would consider too little to live on, would cost almost $3 trillion. But if you means-test it to control the cost, or try to tax most of the benefits back for people who aren’t low-income, you rapidly lose the efficiency gains and start creating some pretty powerful disincentives to work.

$12,000 a year isn’t enough to live on in a major city — which is where a lot of the people you’re hoping to help are living — and providing higher guaranteed income to those living in more expensive areas will create an incentive that will draw more people into the qualifying areas. Excluding immigrants from the benefits will exacerbate the already serious problems some areas have with their illegal immigrants (and create yet another barrier for legal immigrants over and above what is already in their way, as documented here).

Switzerland is reported to be considering a guaranteed income plan. As Megan says, it’ll be an interesting experiment if they do:

In general, I am wary of exciting results from small pilot programs. Most of those programs fail when they’re rolled out statewide, either because the result was spurious or because the exciting work of a small, dedicated group just can’t be replicated in a gargantuan state bureaucracy.

I will be very happy if Switzerland decides to mail a check for a couple of thousand dollars to every citizen every month; it will be fascinating to see what results this has. But I am skeptical that those results will, on net, be good ones.

In short, if there are any positive externalities to governments spending vast sums to erect baseball, basketball, football, or hockey facilities for professional teams … most of the profit is captured by the well-connected and doesn’t benefit the communities who put up the money. I’ve linked to several articles that debunk the usual claims about how building this team a new stadium will provide so many millions of dollars in new spending, and the story always seems to be the same, regardless of the location of the latest corporate welfare pitch.

Earlier this year, Neil deMause linked to this Tampa Bay Times analysis of the local economic impact of the Tampa Bay Rays:

In 2008, Matheson studied sports projects from across the country to see if taxable sales rose after stadiums were built. The study also examined whether tax collections dipped when sports leagues shut down for strikes or lockouts.

“There was simply not any bump at all,” Matheson said.

Tax collections were as likely to drop as rise when a team started play in a new city. And collections dropped during some strikes, but rose during others.

The main reason relates to how spending ripples through an economy, said Dennis Coates, an economist at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County.

When a couple spends $100 for dinner and a movie, much of that money goes to waiters, ticket takers and other local workers and suppliers. Those people, in turn, spend their paychecks on rent, food and other sectors of the local economy.

Each dollar of original spending can contribute $3 to $4 to economic activity and job creation.

Professional sports mute this ripple effect.

“Spending that goes on inside a stadium tends to flow into the pockets of a relatively few, high-income individuals who live a large portion of the year outside the city,” Coates said. “Much of that money flows out.”

[…]

Sports franchises also drain an economy by soaking up taxpayer money that could go to other city services or tax relief — both of which stimulate economic activity.

In her 2005 study, the “Full Count,” Harvard University professor Judith Grant Long pegged Tropicana Field’s public subsidy at 130 percent of its construction cost, one of the highest public shares in the country.

“The real cost of public subsidies for sports facilities is significantly higher than commonly reported,” Long wrote. “Public costs associated with the operation of the facility and foregone property taxes are routinely ignored.”

The best face on Rays economic impact came from two 2008 studies that indicated that baseball bolsters tourism revenues to the tune of $100 million to $200 million a year.

Tourism analysis is an optimistic approach because it focuses only on dollars flowing into the area without examining how baseball might sap local spending levels.

At Field of Schemes, Neil deMause also notes:

The economists note other reasons why sports spending is overblown (some studies could be double-counting fans for each game that they attend even if they’re in town for an entire series, among other things); the whole article is worth reading. And when you’re done with that, check out Shadow of the Stadium’s rundown of other reports on how economists nearly unanimously agree that stadium subsidies are a really, really bad idea. Not that economists are always right, but it should if nothing else put the burden of proof on team owners to show why the heck they should be getting hundreds of millions of dollars in public cash, when nobody can spot any significant public benefits.

In Forbes, Tim Worstall explains a misunderstanding of Ricardo’s Iron Law of One Price on the part of the Guardian:

This is a fun little bit of data calculation and visualisation. It’s a database and then mapping of the global price list for Apple’s iPhone 5s. And there are two interesting ways of using it. The first is simply to look at how prices differ around the world:

You can do this in USD or GBP as you wish. And this can be used to explore the violations of Ricardo’s Iron Law of One Price. Which is where David Ricardo insisted that the prices of traded goods would inevitably move to being equal all over the world. Well, equal minus the transport costs of getting them around the world. And transport costs for an iPhone are trivial: it would be amazing if Apple were paying more than a couple of dollars to airfreight one to anywhere at all. So, we would expect prices to be the same everywhere: but they obviously are not.

[…]

However, when The Guardian reports on this something appears to go wrong. Not their fault I suppose, it’s about economics and lefties never really do get that subject. But here:

Similar to the way the Economist tracks the cost of the ubiquitous McDonalds burger across countries, nations and states, Mobile Unlocked tracked the price of the iPhone 5S across 47 countries in native currencies with native sales tax, and then converted those prices into US dollars (USD) or British pounds (GBP).

No … the Big Mac Index operates entirely and exactly the other way around. We need to make the distinction between traded goods and non-traded goods. The Iron Law only works on traded goods. What we’re trying to find out with PPP calculations is what are the price differentials of non-traded goods? Which is why the Big Mac is used. It is (supposedly at least) exactly the same all over the world. It is also made almost entirely from local produce bought at the local price in local markets. US Big Macs use American beef, Argentine ones Argentine and so on. So we get to see the impact of local prices on the same product worldwide. That’s what we’re actually attempting with that Big Mac Index. The Economist then goes on to compare the prices of this non-traded good with exchange rates and attempt to work out whether the exchange rates are correct or not.

This is entirely different from using the price of a traded good to measure local price variations. For what we’re going to be measuring here is what interventions there are into stopping the Iron Law working, not what local price levels are.

In the latest Libertarian Enterprise, L. Neil Smith provides a thumbnail sketch of the reasons for the first amendments to the US constitution:

While some of this nation’s Founding Fathers — Thomas Jefferson, Patrick Henry, George Mason — were intent, first and foremost, to create a new country in which individual liberty and free enterprise would be the order of the day, there were others, like Alexander Hamilton, who regarded the fledgling America as his personal piggy bank.

You will have been taught that the Articles of Confederation, our first “operating system” were deeply flawed, The truth is that they provided for an extremely decentralized governance that stood as an obstacle to the vast fortunes Hamilton and his cronies had hoped to amass.

The Articles had to go, and it is revealing that among Hamilton’s first acts as Treasury Secretary under the Constitution that replaced them was a national excise tax on whiskey that, as readers of my novel The Probability Broach know, very nearly sparked a second American Revolution.

Corn farmers of western Pennsylvania long accustomed to turning their crop into a less perishable, more transportable product, were among the first victims of democracy American-style, the kind where three coyotes and a lamb sit down to debate on what’s going to be for dinner.

Nevertheless, that’s why a few stiff-necked libertarian-types, like Jefferson, held out for a Bill of Rights to be added to the new Constitution, and it was written, more or less to Jefferson’s order, by his close friend, James Madison, one of the few Federalists who was genuinely interested in assuaging the Anti-Federalists about the new document.

The Bill of Rights was, unfortunately misnamed. It was not a list of things Americans were allowed too do, under the Constitution. It was and remains a list of things government is absolutely forbidden to do — like set up a state religion, or steal your house — under any circumstances.

The Bill of Rights was the make-or-break condition that allowed the Constitution to be ratified. No Bill of Rights, no Constitution. And since all political authority in America “trickles down” from the Constitution, no Constitution no government. And, since the Bill of Rights was passed as a unit, a single breach, in any one of the ten articles, breaches them all and with them, the entire Constitution. Every last bit of the authority that derives from it becomes null and void.

Tim Worstall explains why it would make no sense whatsoever to impose taxes on the winnings from betting:

The point about betting of all types, including this spread betting, is that the winnings of some people are, and must be, entirely offset by the losses of others. Yes, certainly, there are companies in the middle who organise things and they are taxed on their earnings and profits in the usual manner. But the winnings of some punters come from the losses of others.

It’s also a pretty standard part of the UK taxation system that if there is going to be tax charged on the income or profits of something then there will also be an equal allowance against losses on doing that same thing. For example, Gordon Brown changed the law on a company selling a subsidiary: no longer would corporation tax be changed on any profits from doing so. But so also a company could not claim a tax credit for a loss from doing so.

So, if we introduced a tax on betting winnings we would also need to have a system of credits or allowances for betting losses. And here’s the problem with that idea: betting is a less than zero sum game. The winnings of any person or group of people are obviously the losses of all other people betting. So tax charged would be equal to tax credits gained. But it’s worse than that as the bookies are also getting their slice in the middle. Meaning that total winnings are less than total losses. So our credits and allowances for losses would be higher than any revenue gained from the winners.

Powered by WordPress