Marginal Revolution University

Published on 17 Nov 2016The formula for the labor force participation rate is simple: labor force (unemployed + employed) / adult population, excluding people in the military or prison for both.

The total labor force participation rate has grown significantly in the United States since the 1950s. But the total growth doesn’t paint a clear picture of how the U.S. workforce has changed, particularly the makeup.

There are several big factors at play influencing the demographics of labor force participation. For starters, women have entered the labor force in greater numbers since the 1950s. At the same time, technology has altered the types of work available. Manufacturing jobs, which tended to employ lower-skilled, less-educated male workers, gave way to more service jobs requiring more skills and education.

In more recent years, the labor force participation rate, though still much higher than it was half a century ago, has been declining.

There are a number of factors influencing the decline. Many more women are working, but fewer men are employed or actively looking for a job. The United States also has an aging population with many Baby Boomers retiring from the labor force.

In an upcoming video, we’ll take a look at one of the big reasons behind why women have been able to enter and stay in the labor force during peak childbearing years: The Pill.

May 20, 2018

Labor Force Participation

May 8, 2018

QotD: Pay inequality

It probably doesn’t come as news that airline companies pay pilots more than cabin crew — but according to the dogma of the gender wage gap, we’re supposed to find this fact troubling. The British government now requires companies to report their raw gender gap — that is, the difference in the median hourly wages earned by their male and female employees. Ignoring occupational differences, seniority, employment history, hours worked, or any of the countless other factors affecting salaries, these data are misleading at best. Nevertheless, when budget airline EasyJet reported a 51 percent pay gap between its male and female employees, the company knew that its reputation perched on the edge of a PR abyss.

And that’s the whole point of the exercise: simplify statistics to shock people at the seeming injustice done to women and shame companies into action; refuse to compare similar job functions; ignore the fact that, like every other airline, EasyJet’s pilots are disproportionately male, while their cabin crews skew female; forget that almost all carriers compete for the same 4 percent of the world’s female pilots; and whatever you do, don’t mention that the EasyJet CEO, who was in charge of this bigoted organization and also its highest-paid employee until retiring earlier this year, was a woman. The company should be branded with a scarlet “51 percent” until it … does what? Cuts pilots’ pay? Hikes the salaries of female cabin crew? Hires male attendants instead of female? Goes bankrupt?

Kay S. Hymowitz, “Equal Pay Myths: Activists for wage parity ignore stubborn truths”, City Journal, 2018-04-09.

May 2, 2018

Uses and misuses of the Baltic Dry Index

At the Continental Telegraph, Tim Worstall explains why, for example, Zero Hedge‘s witterings about the changes in the Baltic Dry Index are not actually predictive of boom or bust in the global economy:

As background, the volume of such shipping – dry is referring to dry bulk cargoes, wheat, grains, cement, that is, not container stuff and not oils – is an important indicator of global growth. Trade tends to, tends to note, increase faster than growth itself. If the volume of trade falls off a cliff then we would indeed think that there’s going to be a kablooie in our global GDP figures.

The Baltic Dry is an index of the prices of shipping these cargoes. It’s thus the interaction of the supply of shipping as against the demand for it. That’s rather more than subtly different to the volume of world trade.

The basic background here is that there are reasonably long lead times to get more shipping afloat. And once it is afloat then it tends to stick around for a decade or two. Building the boat is a sunk cost (sorry) so you keep trying to use it as long as income from doing so is above marginal costs, of maintenance and fuel (and maintenance will be skipped in some circumstances) and bugger the mortgage. The supply of shipping is near entirely inelastic on an annual basis, near entirely elastic on a two decade basis.

Demand for shipping is much more elastic in that shorter term. As is usual when we’ve an inelastic supply meeting an elastic demand in a marketplace we get wild price swings. They being what causes that longer term elasticity – as with, say, oil from conventional reservoirs.

The Baltic Dry can drop because more ships are being launched, it can rise because more are scrapped. Not because – note the can here – the volume of trade has changed at all.

What has actually been happening in shipping in general is that the ship owners all looked at how trade was growing before 2008. So, they thought, aha! 5% volume growth! (Numbers here are made up but indicative of the major points) Let’s order more spanking new ships! Which then start arriving in 2010, 2011. Flooding the market with new supply. And shipping volume didn’t grow at 5%. It grew at 2% instead. (Again, these numbers are made up, reflecting memory and thus not accurate, but the relationships between them are about right) So, prices plunge.

But it’s those prices which plunge, not the volume of world trade.

April 19, 2018

The mis-measurement of the digital economy

In the Continental Telegraph, Tim Worstall explains why our current statistical model does not adequately reflect the online world’s contribution to our economy:

To give my favourite current example. WhatsApp is used by some billion people around the world for some to all of their telecoms needs. It turns up in economic statistics as a reduction in productivity.

That’s mad.

In more detail, WhatsApp is free to use and carries no advertising. That means there’s no sale associated with it. We measure consumption at market prices – a price of $0 means no consumption. Consumption is one of the three ways we measure GDP – each of the three should be the same as the other two but isn’t because lying about taxes.

The other two calculations are all incomes, or all production. Things that are sold at no price do not add to production given that we measure it at market prices.

Income, well, there’re 200 or so engineers at Facebook who work on it (I checked with Facebook itself). Say their salary is $250k a year each. Probably too low but we’ve got to use some number or other. $50 million then. That’s incomes added to GDP.

So, in our three methods of calculating GDP – they should all be the same but that doesn’t matter here – we’ve value of WhatsApp (more accurately, WhatsApp adds value of $x each year to the global economy) of $50 million. Or $0 or $0.

April 14, 2018

Alcohol and health – if you torture the data long enough, it will give you the answer you want

Tim Worstall isn’t convinced that a recent study summarized in The Lancet is either honest or useful:

We have a new study out, in the Lancet no less, telling us that the new, lower, limits for reasonable alcohol consumption are just right. Well, of course the report says that, right? The problem being that it’s entirely contrary to the more general experience we’ve got of booze consumption. For, yes indeedy, there’s a level of drinking which will – as always, on average – shorten life. But our experience to date is that it’s several times what is the current measure of safe consumption. This basic understanding of ours being that no booze lowers lifespan, too much lowers it, a modicum increases it. The argument being the definition of modicum of course.

Observation of large populations being that modicum is anything from some up to perhaps 40 or even 50 units a week. This isn’t what the current study shows at all […]

I’m not in any manner a medical expert but that does look odd. 5 million observation years on half a million people, looks like 10 years on average per person. They’re using this to predict lifespan at age 40? When lifespan at 40 is, these days, a further 40 to 50 years or so? OK, maybe there’s some sekkrit decoder ring for epidemiologists here but anyone want to try and explain it?

Ah:

We focused our study on current alcohol drinkers

So the comparison doesn’t include those who don’t drink. We’re not therefore getting a baseline of no alcohol consumption to compare with. That is, by design, the study excludes the known to be higher death rates (or lower lifespans) of the temperance types. No, really:

Third, never-drinkers might differ systematically from drinkers in ways that are difficult to measure, but which might be relevant to disease causation.

Our more general stats do indeed say that heavy drinkers (that 40 to 50 unit level perhaps) and never drinkers have about the same lifespans. Quick, gotta exclude that information, eh?

As far as we’re concerned that’s probably enough. We’ll see what Snowdon has to say about it, shall we? Because this finding is contrary to pretty much everything else we know about booze consumption. Explaining why it is will be important.

Update, 15 April: It’s no wonder that people are confused about the benefits and/or drawbacks of drinking…

What you end up with when drawing strong conclusions based on non-experimental data with selection bias, lots of measurement error and dodgy comparison groups. (h/t: @RadaWilinofsky) pic.twitter.com/iUZQbTh6sB

— Amir Sariaslan (@AmirSariaslan) April 14, 2018

March 27, 2018

Metrics are merely a tool. Like any tool they can be misused.

A big problem with depending on metrics is finding things to count that are actually useful measurements of whatever you’re tracking. A lot of bad management decisions can be traced to poorly chosen metrics. As a general rule, just because something can be measured doesn’t automatically mean that measurement will be useful. Tim Harford reviews a recent book on metrics:

Jerry Z Muller’s latest book is 220 pages long, not including the front matter. The average chapter is 10.18 pages long and contains 17.76 endnotes. There are four cover endorsements and the book weighs 421 grammes. These numbers tell us nothing, of course. If you want to understand the strengths and weaknesses of The Tyranny of Metrics you will need to read it — or trust the opinion of someone who has.

Professor Muller’s argument is that we keep forgetting this obvious point. Rather than rely on the informed judgment of people familiar with the situation, we gather meaningless numbers at great cost. We then use them to guide our actions, predictably causing unintended damage.

A famous example is the obsession, during the Vietnam war, with the “body count” metric embraced by US defence secretary Robert McNamara. The more of the enemy you kill, reasoned McNamara, the closer you are to winning. This was always a dubious idea, but the body count quickly became an informal metric for ranking units and handing out promotions, and was therefore often exaggerated. Counting bodies became a risky military objective in itself.

This episode symbolises the mindless, fruitless drive to count things. But it also shows us why metrics are so often used: McNamara was trying to understand and control a distant situation using the skills of a generalist, not a general. Muller shows that metrics are often used as a substitute for relevant experience, by managers with generic rather than specific expertise.

Muller does not claim that metrics are always useless, but that we expect too much from them as a tool of management. For example, if a group of doctors collect and analyse data on clinical outcomes, they are likely to learn something together. If bonuses and promotions are tied to the numbers, the exercise will teach nobody anything and may end up killing patients. Several studies have found evidence of cardiac surgeons refusing to operate on the sickest patients for fear of lowering their reported success rates.

March 8, 2018

Frictional Unemployment

Marginal Revolution University

Published on 1 Nov 2016Finding a job can be kind of like dating. When a new graduate enters the labor market, she may have the opportunity to enter into a long-term relationship with several companies that aren’t really a good fit. Maybe the pay is too low or the future opportunities aren’t great. Before settling down with the right job, this person is still considered unemployed. Specifically, she’s experiencing frictional unemployment.

In the United States’ dynamic economy, this is a common state of short-term unemployment. Companies are often under high levels of competition and frequently evolve. They go out of business or have to lay off workers. Or maybe the worker quits to find a better position. In fact, millions of separations and new hires occur every month accompanied by short periods of unemployment.

Frictional unemployment helps allocate human capital (i.e. workers) to its highest valued use. Hopefully, workers are similarly finding themselves with more fulfilling jobs. Even when it’s caused by an event such as a firm going out of business, frictional unemployment is a normal part of a healthy, growing economy.

March 2, 2018

Defining the Unemployment Rate

Marginal Revolution University

Published on 18 Oct 2016How is unemployment defined in the United States?

If someone has a job, they’re defined as “employed.” But does that mean that everyone without a job is unemployed? Not exactly.

A minor without a job isn’t unemployed. Someone who has been incarcerated also isn’t counted. A retiree, too, does not count toward the unemployment rate.

For the official statistics, you have to meet quite a few criteria to be considered unemployed in the U.S. For instance, if you’re without a job, but have actively looked for work in the past four weeks, you are considered unemployed.

In times of recession, when people are faced with long-term unemployment and lots of discouragement, the official rate might not count some of the people that you would otherwise consider unemployed.

This video will give you a clear picture of how the unemployment rate is defined and build a foundation for further understanding this important facet of labor markets.

February 25, 2018

QotD: Trade deficits

No economic statistic is reported more dolefully these days than the country’s trade balance.

Ever on the alert for signs of impending economic disaster, the press routinely couples reports of record monthly trade deficits with warnings of experts and Government officials of the dangers of the deficit.

Just what is so dangerous about receiving more goods from foreigners than we give them back is never actually explained, but it is often suggested that that it causes a loss of American jobs.

News reports sometimes even provide estimates of the number of jobs lost owing to every billion dollar increase in the trade deficit. Heaven only knows how these estimates are made, but presumably they are based on the assumption that imports deprive Americans of jobs they could have had producing domestic substitutes for the imports.

It almost seems tedious to do so, but it apparently still needs to be pointed out that buying less from foreigners means that they will buy less from us for the simple reason that they will have fewer dollars with which to purchase our products.

Thus, even if reducing imports increases employment in industries that compete with imports, it must also reduce employment in export industries.

Moreover, the notion that the trade deficit destroys domestic jobs is contradicted by the tendency of the deficit to increase during economic expansions and to decrease during contractions.

The demand for imports rises with income, so imports normally tend to rise faster than exports when a country expands more rapidly than its trading partners. The trade deficit is a symptom or rising employment — not the cause of rising unemployment.

That balance-of-trade figures are misunderstood and misused is not surprising, since their function has never been to inform or to enlighten. Their real purpose is to provide spurious statistical and pseudo-scientific support to groups seeking protectionist legislation. These groups try to cloak their appeals to protection with an invocation of the general interest in a favorable balance of trade.

David Glasner, “What’s So Bad about the Trade Deficit?”, Uneasy Money, 2016-06-02 (originally published in the New York Times in 1984).

February 24, 2018

Is Unemployment Undercounted?

Marginal Revolution University

Published on 25 Oct 2016You may recall from our previous video that to be counted in the official unemployment rate in the U.S., you have to be an adult without a job and have actively looked for work within the past four weeks. That means that if someone has given up looking for a job, even if they want one, they are no longer counted under the official definition.

Does this mean that unemployment is undercounted? In other words, is the unemployment rate in fact higher than is reported?

Some have claimed this to be the case. However, unemployment is a tricky statistic. It’s important to consider that adults without jobs can fall into different categories. Many retirees, for example, are willing to leave retirement and take a job for the right price. If we are counting people that aren’t actively looking for employment, shouldn’t the retirees also be considered unemployed?

The simplest solution to this conundrum is to only count unemployed adults actively seeking work.

But what about discouraged workers — those who are unemployed and have not sought work in the past four weeks, but have sought work in the past year. Should we consider them in our calculations?

There are actually six different unemployment rates measured by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. The various rates have less and more stringent criteria. The official rate, called U3, falls somewhere in the middle. Another rate, called U4, does include discouraged workers in its calculation. All six rates follow a similar track over time.

So while the official unemployment rate may not be perfect, it does provide us with a good indicator of the state of the labor market and where it’s headed.

February 19, 2018

Graphing good news

In the Times Literary Supplement, David Wootton reviews Enlightenment Now: A manifesto for science, reason, humanism and progress by Steven Pinker:

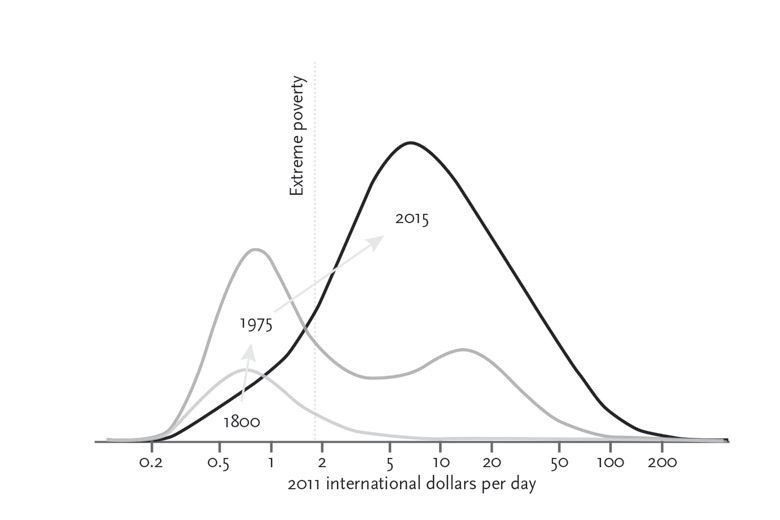

This book consists essentially of seventy-two graphs – and, despite that, it is gripping, provocative and (many will find) infuriating. The graphs all have time on the horizontal axis, and on the vertical axis something important that can be measured against it – life expectancy, for example, or suicide rates, or income. In some graphs the line, or lines (often the graphs compare trends in several countries) fall as they go from left to right; in others they rise. In every single one, the overall picture (with the inevitable blips and bounces) is of life getting better and better. Suicide rates fall, homicides fall, incomes rise, life expectancies rise, literacy rates rise and so on and on through seventy-two variations. Most of these graphs are not new: some simply update graphs which appeared in Pinker’s earlier The Better Angels of Our Nature (2011); others come from recognized purveyors of statistical information. The graphs that weren’t in Better Angels extend the argument of that book, that war and homicide are on the decline across the globe, to assert that life has been getting better and better in all sorts of other respects. The claim isn’t new: a shorter version is to be found in Johan Norberg’s Progress (2017). But the range and scope of the evidence adduced is new. The only major claim not supported by a graph (or indeed much evidence of any kind) is the assertion that all this progress has something to do with the Enlightenment.

Since the argument of the book is almost entirely contained in the graphs, those who want to attack the argument are going to attack the figures on which the graphs are based. Good luck to them: arguments based on statistics, like all interesting arguments, should be tested and tested again. Better Angels caused a vitriolic dispute between Pinker and Nassim Nicholas Taleb as to whether major wars are becoming less frequent. In Taleb’s view the question is a bit like asking whether major earthquakes are getting less frequent or not: they happen so rarely, and so randomly, that you would need records going back over a vast stretch of time to reach any meaningful conclusion; a graph showing falling death rates in wars over the past seventy years won’t do the job. But it certainly will tell you that lots of generalizations about modern war are wrong. Much, indeed most, of Pinker’s argument survived Taleb’s attack, which in any case was directed at only one graph among many.

A more radical line of criticism of Better Angels came from John Gray. How can one find a common standard of measurement for the suffering of a concentration camp victim, of a soldier who died in the trenches, and of someone killed in the firebombing of Dresden? To turn to economics, how can one find a common standard of measurement for books and washing machines, oranges and steak pies? Money, you might think, provides that standard, but what happens if many of the goods being measured – electric lighting, cars, televisions, computers – get cheaper and cheaper as time goes on, so that a rising standard of living is concealed by falling prices? For Gray, to place one’s faith in statistics, which claim to be measuring the unmeasurable, is no different from believing in conversations with angels or in the efficacy of Buddhist prayer wheels. Quantification is our religion.

February 17, 2018

Only 3.8% of American adults identify themselves as LGBT

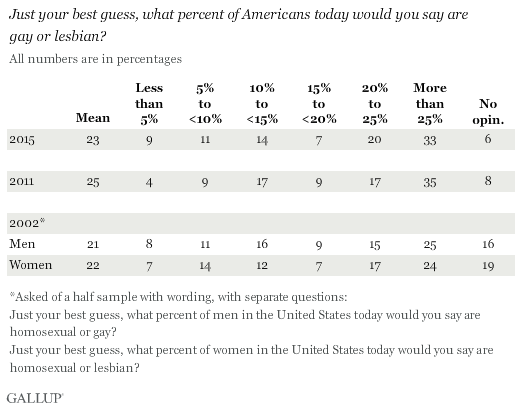

Most people guess a much higher percentage, and if the poll was restricted to the under-30s, the number would likely be at least twice as high. The poll is a few years old now, but it points out that most Americans over-estimate the number of gays and lesbians in the population:

The American public estimates on average that 23% of Americans are gay or lesbian, little changed from Americans’ 25% estimate in 2011, and only slightly higher than separate 2002 estimates of the gay and lesbian population. These estimates are many times higher than the 3.8% of the adult population who identified themselves as lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender in Gallup Daily tracking in the first four months of this year.

The stability of these estimates over time contrasts with the major shifts in Americans’ attitudes about the morality and legality of gay and lesbian relations in the past two decades. Whereas 38% of Americans said gay and lesbian relations were morally acceptable in 2002, that number has risen to 63% today. And while 35% of Americans favored legalized same-sex marriage in 1999, 60% favor it today.

The U.S. Census Bureau documents the number of individuals living in same-sex households but has not historically identified individuals as gay or lesbian per se. Several other surveys, governmental and non-governmental, have over the years measured sexual orientation, but the largest such study by far has been the Gallup Daily tracking measure instituted in June 2012. In this ongoing study, respondents are asked “Do you, personally, identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender?” with 3.8% being the most recent result, obtained from more than 58,000 interviews conducted in the first four months of this year.

H/T to Gari Garion for the link.

February 15, 2018

QotD: Computer models

How can one be certain about outcomes in a complex system that we’re not really all that good at modeling? Anyone who’s familiar with the history of macroeconomic modeling in the 1960s and 1970s will be tempted to answer “Umm, we can’t.” Economists thought that the explosion of data and increasingly sophisticated theory was going to allow them to produce reasonably precise forecasts of what would happen in the economy. Enormous mental effort and not a few careers were invested in building out these models. And then the whole effort was basically abandoned, because the models failed to outperform mindless trend extrapolation — or as Kevin Hassett once put it, “a ruler and a pencil.”

Computers are better now, but the problem was not really the computers; it was that the variables were too many, and the underlying processes not understood nearly as well as economists had hoped. Economists can’t run experiments in which they change one variable at a time. Indeed, they don’t even know what all the variables are.

This meant that they were stuck guessing from observational data of a system that was constantly changing. They could make some pretty good guesses from that data, but when you built a model based on those guesses, it didn’t work. So economists tweaked the models, and they still didn’t work. More tweaking, more not working.

Eventually it became clear that there was no way to make them work given the current state of knowledge. In some sense the “data” being modeled was not pure economic data, but rather the opinions of the tweaking economists about what was going to happen in the future. It was more efficient just to ask them what they thought was going to happen. People still use models, of course, but only the unflappable true believers place great weight on their predictive ability.

Megan McArdle, “Global-Warming Alarmists, You’re Doing It Wrong”, Bloomberg View, 2016-06-01.

February 4, 2018

Sword Bayonets – German Casualties – Jerusalem Occupation I OUT OF THE TRENCHES

The Great War

Published on 3 Feb 2018Check our Podcast: http://bit.ly/MedievalismWW1Podcast

Chair of Wisdom Time! This week we talk about possibly fabricated German casualty numbers, the unwieldy WW1 bayonets and the reaction to the occupation of Jerusalem.

January 19, 2018

What “killed” the most tanks in World War 2?

Military History Visualized

Published on 22 Dec 2017This video discusses what killed the most tanks in World War 2. Was it anti-tank guns, mines, planes, hand-held anti-tank weapons, mechanical breakdowns, etc. Also a short look at the problems of the term “kill”, e.g., mobility, firepower and catastrophic/complete kill.

Original Question by Christopher: “What destroyed the most tanks during WW2: infantry, planes, anti-tank guns, or other tanks (I’m not sure if tank destroyers needs its own category or not).”