Earlier this year, I had occasion to run a Google search for “Mr Gameway’s Ark” (it’s still almost unknown: the Googles, they do nothing). However, I did find a very early post on the old site that I thought deserved to be pulled out of the dusty archives, because it explains why I can — to this day — barely stand to listen to “Little Drummer Boy”:

Seasonal Melodies

James Lileks has a concern about Christmas music:

This isn’t to say all the classics are great, no matter who sings them. I can do without “The Little Drummer Boy,” for example.

It’s the “Bolero” of Christmas songs. It just goes on, and on, and on. Bara-pa-pa-pum, already. Plus, I understand it’s a sweet little story — all the kid had was a drum to play for the newborn infant — but for anyone who remembers what it was like when they had a baby, some kid showing up unannounced to stand around and beat on the skins would not exactly complete your mood. Happily, the song has not spawned a sequel like “The Somewhat Larger Cymbal Adolescent.”

This reminds me about my aversion to this particular song. It was so bad that I could not hear even three notes before starting to wince and/or growl.

Back in the early 1980’s, I was working in Toronto’s largest toy and game store, Mr Gameways’ Ark. It was a very odd store, and the owners were (to be polite) highly idiosyncratic types. They had a razor-thin profit margin, so any expenses that could be avoided, reduced, or eliminated were so treated. One thing that they didn’t want to pay for was Muzak (or the local equivalent), so one of the owners brought in his home stereo and another one put together a tape of Christmas music.

Back in the early 1980’s, I was working in Toronto’s largest toy and game store, Mr Gameways’ Ark. It was a very odd store, and the owners were (to be polite) highly idiosyncratic types. They had a razor-thin profit margin, so any expenses that could be avoided, reduced, or eliminated were so treated. One thing that they didn’t want to pay for was Muzak (or the local equivalent), so one of the owners brought in his home stereo and another one put together a tape of Christmas music.

Note that singular. “Tape”.

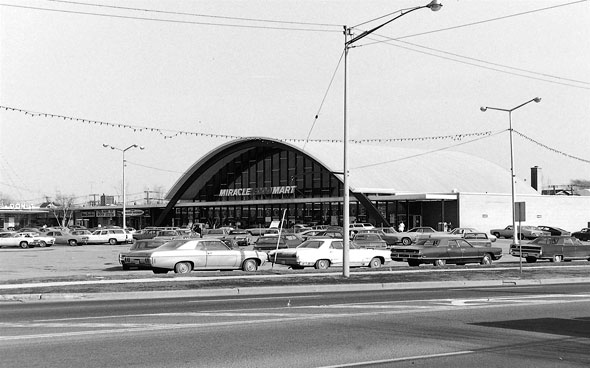

An ad from the year of Trivial Pursuit (via OSRcon)

Christmas season started somewhat later in those distant days, so that it was really only in December that we had to decorate the store and cope with the sudden influx of Christmas merchandise. Well, also, they couldn’t pay for the Christmas merchandise until sales started to pick up, so that kinda accounted for the delay in stocking-up the shelves as well …

So, Christmas season was officially open, and we decorated the store with the left-over krep from the owners’ various homes. It was, at best, kinda sad. But — we had Christmas music! And the tape was pretty eclectic: some typical 50’s stuff (“White Christmas” and the like), some medieval stuff, some Victorian stuff and that damned “Drummer Boy” song.

We were working ten- to twelve-hour shifts over the holidays (extra staff? you want Extra Staff, Mr. Cratchitt???), and the music played on. And on. And freaking on. Eternally. There was no way to escape it.

To top it all off, we were the exclusive distributor for a brand new game that suddenly was in high demand: Trivial Pursuit. We could not even get the truck unloaded safely without a cordon of employees to keep the random passers-by from trying to grab boxes of the damned game. When we tried to unpack the boxes on the sales floor, we had customers snatching them out of our hands and running (running!) to the cashier. Stress? It was like combat, except we couldn’t shoot back at the buggers.

Oh, and those were also the days that Ontario had a Sunday closing law, so we were violating all sorts of labour laws on top of the Sunday closing laws, so the Police were regular visitors. Given that some of our staff spent their spare time hiding from the Police, it just added immeasurably to the tension levels on the shop floor.

And all of this to the background soundtrack of Christmas music. One tape of Christmas music. Over and over and over and over and over and over and over again.

It’s been over 20 [now 30] years, and I still feel the hackles rise on the back of my neck with this song … but I’m over the worst of it now: I can actually listen to it without feeling that all-consuming desire to rip out the sound system and dance on the speakers. After two decades.

Back in the early 1980’s, I was working in Toronto’s largest toy and game store, Mr Gameways’ Ark. It was a very odd store, and the owners were (to be polite) highly idiosyncratic types. They had a razor-thin profit margin, so any expenses that could be avoided, reduced, or eliminated were so treated. One thing that they didn’t want to pay for was Muzak (or the local equivalent), so one of the owners brought in his home stereo and another one put together a tape of Christmas music.

Back in the early 1980’s, I was working in Toronto’s largest toy and game store, Mr Gameways’ Ark. It was a very odd store, and the owners were (to be polite) highly idiosyncratic types. They had a razor-thin profit margin, so any expenses that could be avoided, reduced, or eliminated were so treated. One thing that they didn’t want to pay for was Muzak (or the local equivalent), so one of the owners brought in his home stereo and another one put together a tape of Christmas music.