The Australasian Antarctic Expedition (AAE) has run into far harsher sea and ice conditions than they’d banked on, and it raises questions about the scientific validity of the expedition:

The Australasian Antarctic Expedition (AAE) has run into far harsher sea and ice conditions than they’d banked on, and it raises questions about the scientific validity of the expedition:

The purpose of the AAE expedition was to take a science team of 36 women and men south to discover just how much change has taken place at Mawson Station over 100 years. The expedition was also intended to replicate the original AAE led by explorer Sir Douglas Mawson a century ago, in 1913. The new expedition was to be led by Prof. Chris Turney, a publicity-hungry professor of climate change at Australia’s University of New South Wales.

Also the expedition was designed to generate lots of publicity. Along the scientists and ship’s crew were 4 journalists from leading media outlets who would feed news regularly, and later report extensively on the results and findings. All this in turn would bring loads of attention to a region that is said to be threatened by global warming. The AAE’s donation website even states that the expedition’s purpose is to collect data and that the findings are “to reach the public and policy makers as soon as possible“.

But expeditions of this type are expensive and funding is not always easy to come by. Costs can run in the millions as special equipment is needed to handle the extremely harsh conditions of the South Pole. Downplaying the conditions to justify cost-cutting by using lower grade equipment rapidly jeopardizes safety.

Inadequate, bargain-price research vessel

The first error expedition leaders made was under-estimating the prevailing sea ice conditions at Mawson Station, their destination. The scientists seemed to be convinced that Antarctica was a warmer place today than it had been 100 years earlier, and thus perhaps they could expect less sea ice there. This in turn would allow them to charter a lighter, cheaper vessel.

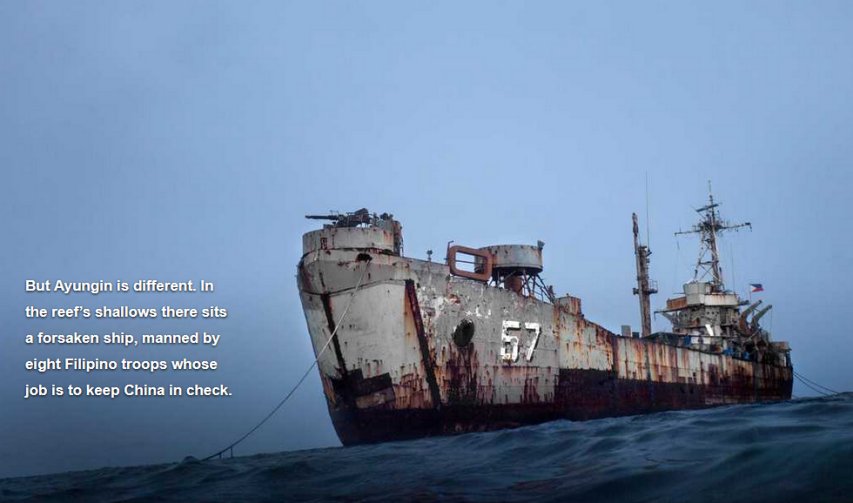

This seems to be the case judging by their choice of seafaring vessel. They chartered a Russian vessel MS Akademik Shokalskiy, an ice-strengthened ship built in Finland in 1982. According to Wikipedia the ship has two passenger decks, with dining rooms, a bar, a library, and a sauna, and accommodates 54 passengers and a crew of up to 30. Though it is ice-reinforced, it is not an ice-breaker. This is a rather surprising selection for an expedition to Antarctica, especially in view that the AAE website itself expected to travel through areas that even icebreakers at times are unable to penetrate, as we are now vividly witnessing. Perhaps the price for chartering the Russian vessel was too good to pass up.

Luring naïve tourists as a source of cash

What made the expedition even more dubious is that Turney and his team brought on paying tourists in what appears to have been an attempt to help defray the expedition’s costs and to be a source of cheap labor. According to the AAE website, the expedition was costed at US$1.5 million, which included the charter of the Akademik Shokalskiy to access the remote locations. “The site berths on board are available for purchase.” Prices start at $8000!

The expedition brought with it 4 journalists, 26 paying tourists.

Update, 2 January: An editorial in The Australian after news came out that all of the 52 passengers had been rescued from the ice-bound Akademik Shokalskiy:

YOU have to feel a touch of sympathy for the global warming scientists, journalists and other hangers-on aboard the Russian ship stuck in impenetrable ice in Antarctica, the mission they so confidently embarked on to establish solid evidence of melting ice caps resulting from climate change embarrassingly abandoned because the ice is, in fact, so impossibly thick.

[…]

Professor Turney’s expedition was supposed to repeat scientific investigations made by Douglas Mawson a century ago and to compare then and now. Not unreasonably, it has been pointed out Mawson’s ship was never icebound. Sea ice has been steadily increasing, despite the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s gloomy forecasts. Had the expedition found the slightest evidence to confirm its expectation of melting ice caps and thin ice, a major new scare about the plight of the planet would have followed. As they are transferred to sanctuary aboard the icebreaker Aurora Australis, Professor Turney and his fellow evacuees must accept the embarrassing failure of their mission shows how uncertain the science of climate change really is. They cannot reasonably do otherwise.

The 22 crew members will stay on board the vessel until it can be released from the ice (or until another rescue effort needs to be mounted).