It makes no sense to force users to generate passwords for websites they only log in to once or twice a year. Users realize this: they store those passwords in their browsers, or they never even bother trying to remember them, using the “I forgot my password” link as a way to bypass the system completely — effectively falling back on the security of their e-mail account.

Bruce Schneier, “Security Design: Stop Trying to Fix the User”, Schneier on Security, 2016-10-03.

July 24, 2018

QotD: Passwords

June 27, 2018

Canada’s euphemistically named “High Risk Returnees”

Judith Bergman on the Canadian government’s kid-gloves approach to dealing with Canadian citizens who return to Canada after volunteering to serve with terrorist organizations:

Canadians who go abroad to commit terrorism – predominantly jihadists, in other words – have a “right to return” according to government documents obtained by Global News. They not only have a right of return, but “… even if a Canadian engaged in terrorist activity abroad, the government must facilitate their return to Canada,” as one document says.

According to the government, there are still around 190 Canadian citizens volunteering as terrorists abroad. The majority are in Syria and Iraq, and 60 have returned. Police are reportedly expecting a new influx of returnees over the next couple of months.

The Canadian government is willing to go to great (and presumably costly) lengths to “facilitate” the return of Canadian jihadists, unlike the UK, for example, which has revoked the citizenship of ISIS fighters so they cannot return. The Canadian government has established a taskforce, the High Risk Returnee Interdepartmental Taskforce, that, according to government documents:

“… allows us to collectively identify what measures can mitigate the threat these individuals may pose during their return to Canada. This could include sending officers overseas to collect evidence before they depart, or their detention by police upon arrival in Canada.”

Undercover officers may also be used “to engage with the HRT [High Risk Traveler] to collect evidence, or monitor them during their flight home.”

In the sanitizing Orwellian newspeak employed by the Canadian government, the terrorists are not jihadis who left Canada to commit the most heinous crimes, such as torture, rape and murder, while fighting for ISIS in Syria and Iraq, but “High Risk Travelers” and “High Risk Returnees”.

The government is fully aware of the security risk to which it is subjecting Canadians: According to the documents, “HRRs [High Risk Returnees] can pose a significant threat to the national security of Canada”. This fact raises the question of why the government of Canada is keen to facilitate these people’s “right of return” — when presumably the primary obligation of the government is to safeguard the security of law-abiding Canadian citizens.

June 5, 2018

The Internet-of-Things as “Moore’s Revenge”

El Reg‘s Mark Pesce on the end of Moore’s Law and the start of Moore’s Revenge:

… the cost of making a device “smart” – whether that means, aware, intelligent, connected, or something else altogether – is now trivial. We’re therefore quickly transitioning from the Death of Moore’s Law into the era of Moore’s Revenge – where pretty much every manufactured object has a chip in it.

This is going to change the whole world, and it’s going to begin with a fundamental reorientation of IT, away from the “pinnacle” desktops and servers, toward the “smart dust” everywhere in the world: collecting data, providing services – and offering up a near infinity of attack surfaces. Dumb is often harder to hack than smart, but – as we saw last month in the Z-Wave attack that impacted hundreds of millions of devices – once you’ve got a way in, enormous damage can result.

The focus on security will produce new costs for businesses – and it will be on IT to ensure those costs don’t exceed the benefits of this massively chipped-and-connected world. It’ll be a close-run thing.

It’s also likely to be a world where nothing works precisely as planned. With so much autonomy embedded in our environment, the likelihood of unintended consequences amplifying into something unexpected becomes nearly guaranteed.

We may think the world is weird today, but once hundreds of billions of marginally intelligent and minimally autonomous systems start to have a go, that weirdness will begin to arc upwards exponentially.

May 5, 2018

Passwords, again

At The Register, a meditation on passwords by Kieren McCarthy:

“It’s World #PasswordDay! A reminder to change your pins/passwords frequently,” it advised anyone following the hashtag “PasswordDay”. But this, as lots of people quickly pointed out, is terrible advice.

But hang on a second: isn’t that the correct advice? Weren’t all sysadmins basically forced to change their systems to make people reset passwords every few months because it was better for security?

Yes, but that was way back in 2014. Starting late 2015, there was a big push from government departments across the world – ranging from UK spy agency GCHQ to US standard-setting National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and consumer agency the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) – to not do that.

That said, the past few years has been virtually defined by the loss of billions of usernames and passwords from corporations, ranging from your email provider, to your credit agency, home improvement store, retail store and, yes, even government departments.

In that case, does it not in fact make sense to get people to periodically change their passwords? Well, yes. And no.

Yes, because the information would age and so become irrelevant faster. No, because constant resets eat up resources, tend to nudge people toward using simpler passwords, and don’t really make it harder for some miscreant using a brute force attack to guess the password.

[…]

Random or pronounceable?

Everyone agrees that using the word “password” for a password is pretty much the dumbest thing you can do. But so many people still do it that designers have been forced to hardcode a ban on the word into most password systems.

But from there – where do you go? How much better is “password1”? Is it sufficiently better? What about switching letters to other things, like “p@ssw0rd”? Yes, objectively, that is better. But the point is that there are much better ways. And that comes down to basically two choices: random or pronounceable.

The best random password is one that really is random i.e. not a weird spelling that you quickly forget but a combination of letters, numbers and symbols like “4&bqJv8dZrXgp” that you would simply never be able to remember.

But here’s the thing – the reason that particular password is better is largely because in order to use and generate such passwords, you would likely use a password manager. And password managers are great things that we’ll deal with later.

But here’s the thing: if someone is trying to crack your password randomly they are likely to be using automated software that simply fires thousands of possible passwords at a system until it hits the right one.

In that scenario, it is not the gibberish that is important but the length of the password that matters. Computers don’t care if a password is made up of English words – or words of any language. But the longer it is, the more guesses will be needed to get it right.

As our dear truthsayer XKCD points out: “Through 20 years of effort we’ve successfully trained everyone to use passwords that are hard for humans to remember, but easy for computers to guess.”

December 14, 2017

The US Navy and Their Hilariously Inept Search for Dorothy and Her Friends

Today I Found Out

Published on 2 Dec 2017In this video:

While the Ancient Greeks had their celebrated Sacred Band of Thebes, a legendarily successful fighting force made up of all male lovers, in more modern times the various branches of the United States military have not been so accepting of such individuals, which brings us to the topic of today- that time in the 1980s when the Naval Intelligence Service invested significant resources into trying to locate a mysterious woman identified only as “Dorothy” who seemed to have links to countless gay seamen. The plan was to find her and then “convince” her to finger these individuals so the military could give them the boot.

Want the text version?: http://www.todayifoundout.com/index.php/2017/01/u-s-navy-hilarious-multi-million-dollar-fruitless-search-wizard-ozs-dorothy-friends/

October 21, 2017

Canada’s equivalent to the NSA releases a malware detection tool

At The Register, Simon Sharwood looks at a new security tool (in open source) released by the Communications Security Establishment (CSE, formerly known as CSEC):

Canada’s Communications Security Establishment has open-sourced its own malware detection tool.

The Communications Security Establishment (CSE) is a signals intelligence agency roughly equivalent to the United Kingdom’s GCHQ, the USA’s NSA and Australia’s Signals Directorate. It has both intelligence-gathering and advisory roles.

It also has a tool called “Assemblyline” which it describes as a “scalable distributed file analysis framework” that can “detect and analyse malicious files as they are received.”

[…]

The tool was written in Python and can run on a single PC or in a cluster. CSE claims it can process millions of files a day. “Assemblyline was built using public domain and open-source software; however the majority of the code was developed by CSE.” Nothing in it is commercial technology and the CSE says it is “easily integrated in to existing cyber defence technologies.”

The tool’s been released under the MIT licence and is available here.

The organisation says it released the code because its job is to improve Canadian’s security, and it’s confident Assemblyline will help. The CSE’s head of IT security Scott Jones has also told the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation that the release has a secondary goal of demystifying the organisation.

October 12, 2017

That Time Canada Tried to Make a Literal “Gaydar”

Today I Found Out

Published on 10 Oct 2017Never run out of things to say at the water cooler with TodayIFoundOut! Brand new videos 7 days a week!

In this video:

We are all familiar with the colloquialism “gaydar” which refers to a person’s intuitive, and often wildly inaccurate, ability to assess the sexual orientation of another person. In the 1960s, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) attempted to use a slightly more scientific, though equally flawed, approach- a machine to detect if a person was gay or not. This was in an attempt to eliminate homosexuals from the Canadian military, police and civil service. The specific machine, dubbed the “Fruit Machine”, was invented by Dr. Robert Wake, a Carelton University Psychology professor.

Want the text version?: http://www.todayifoundout.com/index.php/2013/06/when-the-canadian-government-used-gay-detectors-to-try-to-get-rid-of-homosexual-government-employees/

October 1, 2017

When network security intersects teledildonics

At The Register, John Leyden warns anyone using an internet-of-things sex toy that their device can be easily detected and exploited by (I kid you not) “screwdrivers” (below the fold, just in case you’re extra-concerned for potentially NSFW content):

June 7, 2017

“Hey, Joey, ‘splain me public key cryptography!”

Joey deVilla explains public key cryptography for non-geeks:

Have you ever tried to explain public-key cryptography (a.k.a. asymmetric cryptography) or the concept of public and private keys and what they’re for to non-techies? It’s tough, and I’ve spent the last little while trying to come up with an analogy that’s layperson-friendly and memorable.

It turns out that it already exists, and Panayotis Vryonis […], came up with it. Go over to his blog and check out the article titled Public-key cryptography for non-geeks. Whenever I have to explain what private keys and public keys are for to someone who’s new to cryptography, I use Vryonis’ “box with special lock and special keys” analogy. Not only does the explanation work, but it’s so good that the people I’ve used it on have used it themselves to explain public-key crypto to others.

I’ve recently used Vryonis’ analogy in a couple of presentations and thought I’d share images from my slides. Enjoy!

April 13, 2017

Microsoft buries the (security) lede with this month’s patch

In The Register, Shaun Nichols discusses the way Microsoft has effectively hidden the extent and severity of security changes in this month’s Windows 10 patch:

Microsoft today buried among minor bug fixes patches for critical security flaws that can be exploited by attackers to hijack vulnerable computers.

In a massive shakeup of its monthly Patch Tuesday updates, the Windows giant has done away with its easy-to-understand lists of security fixes published on TechNet – and instead scattered details of changes across a new portal: Microsoft’s Security Update Guide.

Billed by Redmond as “the authoritative source of information on our security updates,” the portal merely obfuscates discovered vulnerabilities and the fixes available for them. Rather than neatly split patches into bulletins as in previous months, Microsoft has dumped the lot into an unwieldy, buggy and confusing table that links out to a sprawl of advisories and patch installation instructions.

Punters and sysadmins unable to handle the overload of info are left with a fact-light summary of April’s patches – or a single bullet point buried at the end of a list of tweaks to, for instance, Windows 10.

Now, ordinary folk are probably happy with installing these changes as soon as possible, silently and automatically, without worrying about the nitty-gritty details of the fixed flaws. However, IT pros, and anyone else curious or who wants to test patches before deploying them, will have to fish through the portal’s table for details of individual updates.

[…]

Crucially, none of these programming blunders are mentioned in the PR-friendly summary put out today by Microsoft – a multibillion-dollar corporation that appears to care more about its image as a secure software vendor than coming clean on where its well-paid engineers cocked up. The summary lists “security updates” for “Microsoft Windows,” “Microsoft Office,” and “Internet Explorer” without version numbers or details.

March 22, 2017

A check-in from the “libertarian writers’ mafia”

In the most recent issue of the Libertarian Enterprise, J. Neil Schulman talks about “rational security”:

Two of my favorite authors — Robert A Heinlein and Ayn Rand — favored a limited government that would provide an effective national defense against foreign invaders and foreign spies. Rand died March 6, 1982; Heinlein on May 8, 1988 — both of them well before domestic terrorism by foreign nationals or immigrants was a major political issue.

Both Heinlein and Rand, however, were aware of domestic political violence, industrial sabotage, and foreign espionage by both foreigners and immigrants, going back before their own births — Rand February 2, 1905, Heinlein July 7, 1907.

Both Heinlein and Rand wrote futuristic novels portraying totalitarianism (including expansive government spying on its own citizens) within the United States. Both authors also portrayed in their fiction writing and discussed in their nonfiction writing the chaos caused by capricious government control over individual lives and private property.

In their tradition, I’ve done quite a bit of that, also, in my own fiction and nonfiction.

So has my libertarian friend author Brad Linaweaver, whose writings I try never to miss an opportunity to plug.

Brad, like myself, writes in the tradition of Heinlein and Rand — more so even than I do, since Brad also favors limited government while I am an anarchist. Nonetheless I am capable of making political observations and analysis from a non-anarchist viewpoint.

We come to this day in which Brad and I find ourselves without the comfort and living wisdom of Robert A. Heinlein and Ayn Rand. We are now both in our sixties, old enough to be libertarian literary elders.

Oh, we’re not the only ones. L. Neil Smith still writes libertarian novels and opines on his own The Libertarian Enterprise. There are others of our “libertarian writers’ mafia” still living and writing, but none as politically focused as we are — and often, in our opinion, not as good at keeping their eyes on the ball.

January 26, 2017

QotD: Why government intervention usually fails

We saw in an earlier story that the government is trying to tighten regulations on private company cyber security practices at the same time its own network security practices have been shown to be a joke. In finance, it can never balance a budget and uses accounting techniques that would get most companies thrown in jail. It almost never fully funds its pensions. Anything it does is generally done more expensively than would be the same task undertaken privately. Its various sites are among the worst superfund environmental messes. Almost all the current threats to water quality in rivers and oceans comes from municipal sewage plants. The government’s Philadelphia naval yard single-handedly accounts for a huge number of the worst asbestos exposure cases to date.

By what alchemy does such a failing organization suddenly become such a good regulator?

Warren Meyer, “Question: Name An Activity The Government is Better At Than the Private Actors It Purports to Regulate”, Coyote Blog, 2015-06-12.

October 26, 2016

A primer on last week’s IoT DDos attacks

Joey DeVilla provides a convenient layman’s terms description of last Friday’s denial of service attacks on Dyn:

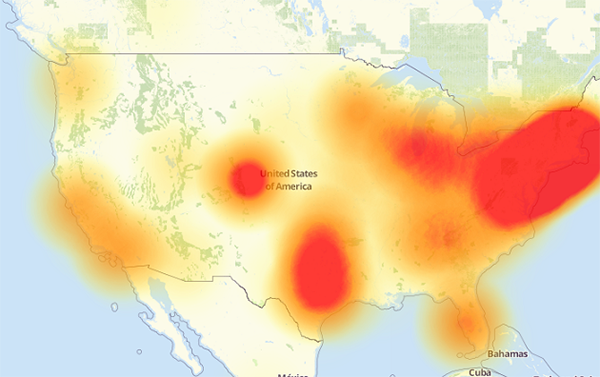

A map of the parts of the internet affected by Friday’s attack. The redder an area is, the more heavily it was affected.

If you’ve been reading about the cyberattack that took place last Friday and are confused by the jargon and technobabble, this primer was written for you! By the end of this article, you’ll have a better understanding of what happened, what caused it, and what can be done to prevent similar problems in the future.

[…]

On Friday, October 21, 2016 at around 6:00 a.m. EDT, a botnet made up of what could be up to tens of millions of machines — a large number of which were IoT devices — mounted a denial-of-service attack on Dyn, disrupting DNS over a large part of the internet in the U.S.. This in turn led to a large internet outage on the U.S. east coast, slowing down the internet for many users and rendered a number of big sites inaccessible, including Amazon, Netflix, Reddit, Spotify, Tumblr, and Twitter.

Flashpoint, a firm that detects and mitigates online threats, was the first to announce that the attack was carried out by a botnet of compromised IoT devices controlled by Mirai malware. Dyn later corroborated Flashpoint’s claim, stating that their servers were under attack from devices located at millions of IP addresses.

The animation above is a visualization of the attack based on the devices’ IP addresses and IP geolocation (a means of approximating the geographic location of an IP address; for more, see this explanation on Stack Overflow). Note that the majority of the devices were at IP addresses (and therefore, geographic locations) outside the United States.

October 14, 2016

QotD: You can’t fix network security by changing the users

Every few years, a researcher replicates a security study by littering USB sticks around an organization’s grounds and waiting to see how many people pick them up and plug them in, causing the autorun function to install innocuous malware on their computers. These studies are great for making security professionals feel superior. The researchers get to demonstrate their security expertise and use the results as “teachable moments” for others. “If only everyone was more security aware and had more security training,” they say, “the Internet would be a much safer place.”

Enough of that. The problem isn’t the users: it’s that we’ve designed our computer systems’ security so badly that we demand the user do all of these counterintuitive things. Why can’t users choose easy-to-remember passwords? Why can’t they click on links in emails with wild abandon? Why can’t they plug a USB stick into a computer without facing a myriad of viruses? Why are we trying to fix the user instead of solving the underlying security problem?

Bruce Schneier, “Security Design: Stop Trying to Fix the User”, Schneier on Security, 2016-10-03.

July 27, 2016

Security concerns with the “Internet of things”

When it comes to computer security, you should always listen to what Bruce Schneier has to say, especially when it comes to the “Internet of things”:

Classic information security is a triad: confidentiality, integrity, and availability. You’ll see it called “CIA,” which admittedly is confusing in the context of national security. But basically, the three things I can do with your data are steal it (confidentiality), modify it (integrity), or prevent you from getting it (availability).

So far, internet threats have largely been about confidentiality. These can be expensive; one survey estimated that data breaches cost an average of $3.8 million each. They can be embarrassing, as in the theft of celebrity photos from Apple’s iCloud in 2014 or the Ashley Madison breach in 2015. They can be damaging, as when the government of North Korea stole tens of thousands of internal documents from Sony or when hackers stole data about 83 million customer accounts from JPMorgan Chase, both in 2014. They can even affect national security, as in the case of the Office of Personnel Management data breach by — presumptively — China in 2015.

On the Internet of Things, integrity and availability threats are much worse than confidentiality threats. It’s one thing if your smart door lock can be eavesdropped upon to know who is home. It’s another thing entirely if it can be hacked to allow a burglar to open the door — or prevent you from opening your door. A hacker who can deny you control of your car, or take over control, is much more dangerous than one who can eavesdrop on your conversations or track your car’s location.

With the advent of the Internet of Things and cyber-physical systems in general, we’ve given the internet hands and feet: the ability to directly affect the physical world. What used to be attacks against data and information have become attacks against flesh, steel, and concrete.

Today’s threats include hackers crashing airplanes by hacking into computer networks, and remotely disabling cars, either when they’re turned off and parked or while they’re speeding down the highway. We’re worried about manipulated counts from electronic voting machines, frozen water pipes through hacked thermostats, and remote murder through hacked medical devices. The possibilities are pretty literally endless. The Internet of Things will allow for attacks we can’t even imagine.

The increased risks come from three things: software control of systems, interconnections between systems, and automatic or autonomous systems. Let’s look at them in turn

I’m usually a pretty tech-positive person, but I actively avoid anything that bills itself as being IoT-enabled … call me paranoid, but I don’t want to hand over local control of my environment, my heating or cooling system, or pretty much anything else on my property to an outside agency (whether government or corporate).