At PJ Media, Athena Thorne asks the most pertinent, relevant question of our times:

Is Donald Trump the Long-Awaited Messiah of the Band ‘Rush’ Era?

Greetings, PJ readers! I hope you all had a wonderful Thanksgiving and are still feeling lazy and slovenly. In that vein, here is a tasty morsel of a column from a friend and fellow reader, Kato the Elder. He makes an excellent argument — one with which I heartily agree — that President-elect Donald Trump is the small-L libertarian hero of our time. Enjoy!

In a particular moment during my precocious, autodidact pre-teen years, I stumbled upon a copy of Ayn Rand’s novel Atlas Shrugged at an estate sale in an old New England barn. There, in a hay-covered stall, I found that dense brick of a book that seemed, in a creepy sort of way, to be waiting for me to pick it up and take it home — consequences be damned. It was like Guy Clark’s song about a haunted guitar, found in a pawn shop, with the name of the next victim to pick it up already written on the case. And, like Guy Clark’s guitar, Atlas Shrugged is one of those cultural objects that once picked up cannot be put down. Who could ever forget, on page 455, where it is asked, “What advice would you give Atlas if he became weary of holding up the world? Shrug.” A libertarian is born. I quickly worked my way through the remainder of Rand’s parables and then the essays.

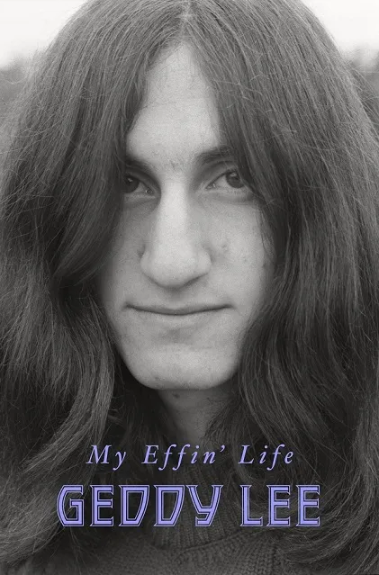

Rand’s novella “Anthem” led to my discovery of the Canadian rock band Rush, which had adapted “Anthem” as the rock opera entitled 2112. It’s the story of a man who suffers under the autocratic rule of the Priests of the Temple of Syrinx, progressives who use computers to create a scientific, expert-driven utopia that does not recognize the value of the individual or the right to think and create and dissent. In “Anthem”, it is the protagonist’s discovery of an ancient incandescent light bulb that leads to the discovery of an earlier and freer society and puts the hero on a collision course with the collectivists. In the Rush version, the long-lost incandescent light bulb is replaced with a guitar, but of course it would be, because what kind of crazy government would take away someone’s light bulbs?

A very strong Randian libertarianism runs through Rush’s music; the heroes of many Rush songs are those individuals struggling, of course, against a government that is determined to pound the individualism and free thought out of its subjects, whether that individual is Tom Sawyer or teenagers living in subdivisions or the teen boy awaiting the world’s applause or the community suffering from mob violence and witch hunts. But Rush, and Rand, are not rejecting the Eisenhower-era type of corporate conformity, but rather the conformity of counter-culture which has taken power and proven the deficiency of the government-expert-knows-best mindset. The epitome of that strain of Randian libertarianism comes in the song “Red Barchetta”, a power ballad about a boy who, in conspiracy with his uncle, escapes to the countryside to race a classic, gas-powered Ferrari against a bland EV car of some kind that has supplanted the freedom and adrenalin rush of gas-powered freedom. Because what kind of crazy government would take away someone’s choice of car?

I saw Rush in concert at least 12 times, and every concert was full of people who looked like me, dressed like me, and sounded like me. We sang along with Rush at the top of our lungs about the freedom of music and the individualism which is closer to the heart. As we all grew older and grayer and our American society became less tolerant of dissent and more dependent on corporate/government cronyism, we could only wonder whether we would find our Howard Rourke, the nonconformist New York developer and architect of Rand’s novel The Fountainhead, who would lead us to the promised land.