A more useful lesson might be skepticism about personalized medicine. Personalized medicine – the idea that I can read your genome and your blood test results and whatever and tell you what antidepressant (or supplement, or form of therapy) is right for you has been a big idea over the past decade. And so far it’s mostly failed. A massively polycausal model would explain why. The average personalized medicine company gives you recommendations based on at most a few things – zinc levels, gut flora balance, etc. If there are dozens or hundreds of things, then you need the full massively polycausal model – which as mentioned before is computationally intractable at least without a lot more work.

(You can still have some personalized medicine. We don’t have to know the causes of depression to treat it. You might be depressed because your grandfather died, but Prozac can still make you feel better. So it’s possible that there’s a simple personalized monocausal way to check who eg responds better to Prozac vs. Lexapro, though the latest evidence isn’t really bullish about this. But this seems different from a true personalized medicine where we determine the root cause of your depression and fix it in a principled way.)

Even if we can’t get much out of this, I think it can be helpful just to ask which factors and sciences are oligocausal vs. massively polycausal. For example, what percent of variability in firm success are economists able to determine? Does most of the variability come from a few big things, like talented CEOs? Or does most of it come from a million tiny unmeasurable causes, like “how often does Lisa in Marketing get her reports in on time”?

Maybe this is really stupid – I’m neither a geneticist or a statistician – but I imagine an alien society where science is centered around polycausal scores. Instead of publishing a paper claiming that lead causes crime, they publish a paper giving the latest polycausal score for predicting crime, and demonstrating that they can make it much more accurate by including lead as a variable. I don’t think you can do this in real life – you would need bigger Big Data than anybody wants to deal with. But like falsifiability and compressability, I think it’s a useful thought experiment to keep in mind when imagining what science should be like.

Scott Alexander, “The Omnigenic Model As Metaphor For Life”, Slate Star Codex, 2018-09-13.

February 4, 2021

QotD: The (as-yet-unfulfilled) promise of “personalized medicine”

January 24, 2021

The Great Wine Blight

The History Guy: History Deserves to Be Remembered

Published 9 Sep 2020In the 19th century, the Great Wine Blight threatened the very existence of grapes. But the pestilence brought into Europe by American vines was eradicated by the use of those very same vines. The History Guy recalls how American indigenous vines saved the wine industry, and how you can help to preserve its future.

This is original content based on research by The History Guy. Images in the Public Domain are carefully selected and provide illustration. As very few images of the actual event are available in the Public Domain, images of similar objects and events are used for illustration.

Special thanks to Stone Hill Winery, Hermann, Missouri:

https://stonehillwinery.comYou can purchase the bow tie worn in this episode at The Tie Bar:

All events are portrayed in historical context and for educational purposes. No images or content are primarily intended to shock and disgust. Those who do not learn from history are doomed to repeat it. Non censuram.

Find The History Guy at:

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/TheHistoryGuyThe History Guy: History Deserves to Be Remembered is the place to find short snippets of forgotten history from five to fifteen minutes long. If you like history too, this is the channel for you.

Awesome The History Guy merchandise is available at:

teespring.com/stores/the-history-guy

Script by CDH

#history #thehistoryguy #wine

January 23, 2021

QotD: “Genetics is interesting as an example of a science that overcame a diseased paradigm”

This side of the veil, instead of looking for the “gene for intelligence”, we try to find “polygenic scores”. Given a person’s entire genome, what function best predicts their intelligence? The most recent such effort uses over a thousand genes and is able to predict 10% of variability in educational attainment. This isn’t much, but it’s a heck of a lot better than anyone was able to do under the old “dozen genes” model, and it’s getting better every year in the way healthy paradigms are supposed to.

Genetics is interesting as an example of a science that overcame a diseased paradigm. For years, basically all candidate gene studies were fake. “How come we can’t find genes for anything?” was never as popular as “where’s my flying car?” as a symbol of how science never advances in the way we optimistically feel like it should. But it could have been.

And now it works. What lessons can we draw from this, for domains that still seem disappointing and intractable?

Turn-of-the-millennium behavioral genetics was intractable because it was more polycausal than anyone expected. Everything interesting was an excruciating interaction of a thousand different things. You had to know all those things to predict anything at all, so nobody predicted anything and all apparent predictions were fake.

Modern genetics is healthy and functional because it turns out that although genetics isn’t easy, it is simple. Yes, there are three billion base pairs in the human genome. But each of those base pairs is a nice, clean, discrete unit with one of four values. In a way, saying “everything has three billion possible causes” is a mercy; it’s placing an upper bound on how terrible genetics can be. The “secret” of genetics was that there was no “secret”. You just had to drop the optimistic assumption that there was any shortcut other than measuring all three billion different things, and get busy doing the measuring. The field was maximally perverse, but with enough advances in sequencing and computing, even the maximum possible level of perversity turned out to be within the limits of modern computing.

(This is an oversimplification: if it were really maximally perverse, chaos theory would be involved somehow. Maybe a better claim is that it hits the maximum perversity bound in one specific dimension)

Scott Alexander, “The Omnigenic Model As Metaphor For Life”, Slate Star Codex, 2018-09-13.

January 4, 2021

QotD: Repressing the facts in genetic research

Now, in 2010, cleared-eyed observers are imagining a near-term future scenario that looks like this: (1) we will shortly have genomic-sequence information on hundreds of thousands of human beings from all over the planet, enough to build a detailed map of human genetic variation and a science of behavioral genetics. (2) We will confirm that variant alleles correlate strongly with significant measures of human ability and character, beginning with IQ and quite possibly continuing to distribution of time preference, sociability, docility, and other important traits. (3) We will discover that these same alleles correlate significantly with traditional indicia of race.

In fact, given the state of our present knowledge, I judge all three of these outcomes are near certain. I have previously written about some of the evidence in Racism and Group Differences. The truth is out there; well known to psychometricians, population geneticists and anyone who cares to look, but surrounded by layers of denial. The cant has become thick enough to, for example, create an entire secondary mythology about IQ (e.g., that it’s a meaningless number or the tests for it are racially/culturally biased). It also damages our politics; many people, for example, avert their eyes from the danger posed by Islamism because they fear being tagged as racists. All this repression has been firmly held in place by the justified fear of truly hideous evils – from the color bar through compulsory sterilization of the “inferior” clear up to the smoking chimneys at Treblinka and Dachau. But … if the repressed is about to inevitably return on us, how do we cope?

It’s not going to be easy. I saw this coming in the mid-1990s, and I’m expecting the readjustment to be among the most traumatic issues in 21st-century politics. The problem with repression, on both individual and cultural levels, is that when it breaks down it tends to produce explosions of poorly-controlled emotional energy; the release products are frequently ugly. It takes little imagination to visualize a future 15 or 20 years hence in which the results of behavioral genetics are seized on as effective propaganda by neo-Nazis and other racist demagogues, with the authority of science being bent towards truly appalling consequences.

Eric S. Raymond, “A Specter is Haunting Genetics”, Armed and Dangerous, 2010-06-19.

December 31, 2020

The limiting factor that holds back the green dream of electric cars everywhere

I’m not actually against the spread of electric vehicles — where appropriate — but we’re a long way technically speaking from an all-electric future on the roads. Alongside the vast increase in our electric generation and distribution infrastructure such a change would require, there’s also the practical limitation of what is currently possible in battery technology, and hoped-for improvements will require significant breakthroughs which seem more than just a step beyond our current capabilities:

“There are liars, damned liars, and battery guys” – or some variation thereof – is an aphorism commonly attributed to US electro-whizz Thomas Edison.

Edison’s anecdotal frustrations remain valid today because scarcely a month goes by without a promised battery revolution, and scarcely a month goes by without that revolution arriving.

In October, for example, The Register encountered Jagdeep Singh, CEO of QuantumScape, a battery startup that boasted a new type of battery that could double the range of electric vehicles, charge in 15 minutes, and is safer than the lithium-ion that dominates the rechargeable market.

“Ten years ago, we embarked on an ambitious goal that most thought was impossible,” Singh said in a canned statement. “Through tireless work, we have developed a new battery technology that is unlike anything else in the world.”

Singh might disprove Edison’s aphorism and deliver the better batteries the world will so clearly appreciate. But to do so he’ll have to buck a 30-year trend that has seen lithium-ion reign supreme.

Why has the industry stalled? The short answer is that chemistry hasn’t found a way to build a better battery.

“The basic concept of what a battery is hasn’t shifted since the 18th century,” says Professor Thomas Maschmeyer, a chemist at the University of Sydney and founding chairman of Gelion Technology, a battery developer. All batteries, Maschmeyer explains, consist of three main building blocks: a positive electrode, called a cathode; a negative electrode, called an anode; and an electrolyte that acts as a catalyst between the two sides. “These three elements cannot change. So, if you want a breakthrough, it must come from a fundamental change in the chemistry,” Maschmeyer says.

Better living through chemistry

Battery boffins have proposed a periodic table’s worth of alternative compounds that could surpass lithium-ion batteries.These largely fall into two categories. First, batteries that are trying to surpass the energy densities that lithium offers, such as solid-state batteries, lithium-sulphur, and lithium-air. The other is batteries comprised of more abundant materials such as sodium-ion batteries, aluminium-ion, and magnesium-ion batteries.

But changing the chemistry of batteries is easier said than done, says Professor Jacek Jasieniak, a professor of material sciences and engineering at Monash University. He compares changing one element in a battery to changing a chemical in a pharmaceutical. “Often solving one problem exacerbates another,” he says.

December 30, 2020

QotD: The sting in the tail of genetic research

A specter is haunting genetics; the shadow of racialist slavery, eugenics, and Naziism. Western civilization since 1945, traumatized by the horror of the Holocaust, has elevated anti-racism into an unquestionable secular piety. Much good has been accomplished thereby, but like all pieties the worthy results have been accompanied by a great deal of willed repression, denial, and cant. Evidence that racial genetic differences do matter is not actually hard to find; Murray & Herrnstein’s The Bell Curve (1994) included a brave and excellent summation of the science on this point. Consequently, the bien-pensant reaction to that book was hysterical vilification, anathematization of heresy in full cry. Even at the time the lurking fear beneath the hysteria was easy to spot – that the authors might, after all, be right, and must be damned even more intensely because they might be.

Eric S. Raymond, “A Specter is Haunting Genetics”, Armed and Dangerous, 2010-06-19.

December 27, 2020

Moderna’s Wuhan Coronavirus vaccine was developed nearly a year ago

Philip Steele explains why Moderna’s vaccine was not made available until very recently, despite having been developed only days after the genetic code for the virus was published:

Few people realize that the Moderna vaccine against COVID-19 — which the FDA has finally declared “highly effective,” and which is now being distributed to Americans — has actually been available for nearly a year.

But the government wouldn’t let you take it.

The vaccine, a triumph of medical science known as mRNA-1273, was designed in a single weekend, just two days after Chinese researchers published the virus’s genetic code on January 11, 2020.

For the entire duration of the pandemic, while hundreds of thousands died and the world economy was decimated by lockdowns, this highly effective vaccine has been available.

But you, and all the people who died, were prohibited by the government from taking it.

There are some who claim that the FDA “saves lives” by putting the brakes on medical innovation with their requirements for years-long, and often decades-long, billion-dollar medical trial procedures.

Missing here is the obvious counterpoint — How many lives did the FDA sacrifice to disease in the meantime?

In the case of COVID-19 we know the answer: more than 300,000 deaths so far in the United States and counting.

November 27, 2020

“The Attack of the Dead Men” Pt.2 – Gas! Gas! Gas! – Sabaton History 095 [Official]

Sabaton History

Published 26 Nov 2020On 22. April 1915, a wall of greenish-yellow fog, up to 2m high, was slowly creeping towards the Allied lines on the Ypres salient. A sweetish-chloric smell preceded the horrific effects of the deadly gas. Coughing, spitting, and retching, men were abandoning their trenches, hurrying to the rear, or falling to the ground, clutching their throats. It was the same desperate, gruesome scenery, the Russian soldiers at Osowiec Fortress had to fight through. From then on, a scientific race to counter and protect against those deadly chemicals began.

Support Sabaton History on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/sabatonhistory

Listen to “Attack of the Dead Men” on the album The Great War: https://music.sabaton.net/TheGreatWar

Watch the Official Lyric Video of “Attack of the Dead Men” here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-AFdw…

Listen to Sabaton on Spotify: http://smarturl.it/SabatonSpotify

Official Sabaton Merchandise Shop: http://bit.ly/SabatonOfficialShopHosted by: Indy Neidell

Written by: Markus Linke and Indy Neidell

Directed by: Astrid Deinhard and Wieke Kapteijns

Produced by: Pär Sundström, Astrid Deinhard and Spartacus Olsson

Creative Producer: Maria Kyhle

Executive Producers: Pär Sundström, Joakim Brodén, Tomas Sunmo, Indy Neidell, Astrid Deinhard, and Spartacus Olsson

Community Manager: Maria Kyhle

Post-Production Director: Wieke Kapteijns

Editor: Karolina Dołęga

Sound Editor: Marek Kamiński

Maps by: Eastory – https://www.youtube.com/c/eastory

Archive: Reuters/Screenocean – https://www.screenocean.comColorizations by:

Adrien Fillon – https://www.instagram.com/adrien.colo…Sources:

– National Archives NARA

– Library of Congress

– Bundesarchiv

– Imperial War Museums: IWM Q 56546, HU67224, Q 60344

– Canadian War Museum

– Auckland Museum

– Wellcome Images

– Icons form The Noun Project: Arrow by 4B Icons, gas bomb by Mete Eraydın, Gas by Andrejs Kirma, Skull by Muhamad Ulum, smoke grenade by 1516All music by: Sabaton

An OnLion Entertainment GmbH and Raging Beaver Publishing AB co-Production.

© Raging Beaver Publishing AB, 2019 – all rights reserved.

November 4, 2020

The replication crisis in all fields is worse than you imagine

It may sound like a trivial issue, but it absolutely is not: scientific studies that can’t be replicated are worthless, yet our lives are often impacted by these failed studies, especially when politicans are guided by junk science results:

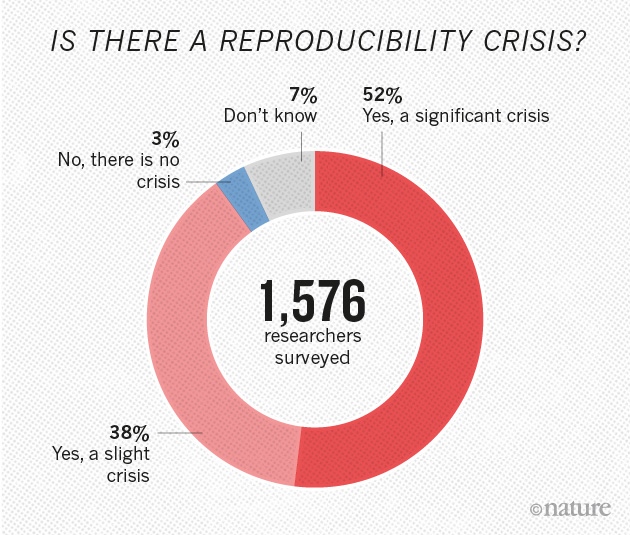

More than 70% of researchers have tried and failed to reproduce another scientist’s experiments, and more than half have failed to reproduce their own experiments. Those are some of the telling figures that emerged from Nature‘s survey of 1,576 researchers who took a brief online questionnaire on reproducibility in research.

The data reveal sometimes-contradictory attitudes towards reproducibility. Although 52% of those surveyed agree that there is a significant ‘crisis’ of reproducibility, less than 31% think that failure to reproduce published results means that the result is probably wrong, and most say that they still trust the published literature.

Data on how much of the scientific literature is reproducible are rare and generally bleak. The best-known analyses, from psychology and cancer biology, found rates of around 40% and 10%, respectively. Our survey respondents were more optimistic: 73% said that they think that at least half of the papers in their field can be trusted, with physicists and chemists generally showing the most confidence.

The results capture a confusing snapshot of attitudes around these issues, says Arturo Casadevall, a microbiologist at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore, Maryland. “At the current time there is no consensus on what reproducibility is or should be.” But just recognizing that is a step forward, he says. “The next step may be identifying what is the problem and to get a consensus.”

Failing to reproduce results is a rite of passage, says Marcus Munafo, a biological psychologist at the University of Bristol, UK, who has a long-standing interest in scientific reproducibility. When he was a student, he says, “I tried to replicate what looked simple from the literature, and wasn’t able to. Then I had a crisis of confidence, and then I learned that my experience wasn’t uncommon.”

The challenge is not to eliminate problems with reproducibility in published work. Being at the cutting edge of science means that sometimes results will not be robust, says Munafo. “We want to be discovering new things but not generating too many false leads.”

September 18, 2020

Was the Wuhan Coronavirus (aka Covid-19) created in a Chinese lab?

Rowan Jacobsen profiles the scientist who believes, based on her own research, that the Wuhan Coronavirus was not a naturally occurring mutation and was instead deliberately created in a Chinese government lab:

It wasn’t long before she came across an article about the remarkable stability of the virus, whose genome had barely changed from the earliest human cases, despite trillions of replications. This perplexed Chan. Like many emerging infectious diseases, COVID-19 was thought to be zoonotic — it originated in animals, then somehow found its way into people. At the time, the Chinese government and most scientists insisted the jump had happened at Wuhan’s seafood market, but that didn’t make sense to Chan. If the virus had leapt from animals to humans in the market, it should have immediately started evolving to life inside its new human hosts. But it hadn’t.

On a hunch, she decided to look at the literature on the 2003 SARS virus, which had jumped from civets to people. Bingo. A few papers mentioned its rapid evolution in its first months of existence. Chan felt the familiar surge of puzzle endorphins. The new virus really wasn’t behaving like it should. Chan knew that delving further into this puzzle would require some deep genetic analysis, and she knew just the person for the task. She opened Google Chat and fired off a message to Shing Hei Zhan. He was an old friend from her days at the University of British Columbia and, more important, he was a computational god.

“Do you want to partner on a very unusual paper?” she wrote.

Sure, he replied.

One thing Chan noticed about the original SARS was that the virus in the first human cases was subtly different — a few dozen letters of genetic code — from the one in the civets. That meant it had immediately morphed. She asked Zhan to pull up the genomes for the coronaviruses that had been found on surfaces in the Wuhan seafood market. Were they at all different from the earliest documented cases in humans?

Zhan ran the analysis. Nope, they were 100 percent the same. Definitely from humans, not animals. The seafood-market theory, which Chinese health officials and the World Health Organization espoused in the early days of the pandemic, was wrong. Chan’s puzzle detectors pulsed again. “Shing,” she messaged Zhan, “this paper is going to be insane.”

In the coming weeks, as the spring sun chased shadows across her kitchen floor, Chan stood at her counter and pounded out her paper, barely pausing to eat or sleep. It was clear that the first SARS evolved rapidly during its first three months of existence, constantly fine-tuning its ability to infect humans, and settling down only during the later stages of the epidemic. In contrast, the new virus looked a lot more like late-stage SARS. “It’s almost as if we’re missing the early phase,” Chan marveled to Zhan. Or, as she put it in their paper, as if “it was already well adapted for human transmission.”

That was a profoundly provocative line. Chan was implying that the virus was already familiar with human physiology when it had its coming-out party in Wuhan in late 2019. If so, there were three possible explanations.

For the record, my strong suspicion is that she is correct about the origins of the virus, but I don’t think it was deliberately released by the Chinese government. I think if it had been deliberate, it would have been much more directly “weaponized” in both delivery mechanism and targeting.

June 27, 2020

QotD: The cost of military equipment

Major military hardware is produced in only limited quantities and involves a massive amount of research, development, and engineering before the first unit goes into service. Because of this, the companies that build it are rarely willing to take the risk of paying for the development themselves and recovering the cost from the units that they sell. What if the customer suddenly decides to cut their buy in half? To avoid this problem, development is paid for by the customer separately from procurement of each item. Well, more or less. The actual answer varies with each particular system, accounting method, and time of the month. But in general, costs break down that way.

So why does this cause so much confusion? Well, it all has to do with what gets reported. Someone who is trying to make the case that some program is outrageously expensive and should be cancelled is going to lump together development and procurement, divide by the number of systems involved, and then publish the resulting number. But, particularly when we’re discussing the cost of a system about to enter production, that’s very different from the actual numbers. To give a well-known example, the B-2 is generally reputed to have cost about $2 billion/plane in the 90s. However, this is the total program cost divided by the 21 airframes. If we’d decided to buy 22 B-2s instead of the 21 we did buy, the extra plane would have cost only $700 million or so. Admittedly, the B-2 is a rather extreme case, and usually the share of R&D cost is less than the procurement (flyaway) cost, but it’s illustrative of the power of this kind of framing.

“bean”, “Military Procurement – Pricing”, Naval Gazing, 2018-03-09.

June 23, 2020

QotD: Scientific discoveries despite “research” and “planning”

We live in a culture of “research” and “planning.” I’m not against honest research (which is rare), but mortally opposed to “planning.” The best it can ever achieve is failure, when some achievement comes despite its ham-fisted efforts. Countless billions, yanked from the taxpayers’ pockets, and collected through highly professional, tear-jerking campaigns, are spent “trying to find a cure” for this or that. When and if it comes, it is invariably the product of some nerd somewhere, with a messy lab. Should it be noticed at all, more billions will be spent appropriating the credit, or more likely, suppressing it for giving “false hope.” The regulators will be called in, as the police are to a crime scene.

For from the “planning” point of view, the little nerd has endangered billions of dollars in funding, and thus the livelihoods of innumerable bureaucratic drudges. That is, after all, why they retain the China Wall of lawyers: to prevent unplanned events from happening. But glory glory, sometimes they happen anyway.

David Warren, “That’s funny”, Essays in Idleness, 2018-03-08.

June 11, 2020

Black Death Mystery Solved – Not Bubonic Plague – Pandemic History 02

TimeGhost History

Published 10 Jun 2020From the day the Black Death starts to ravage humanity in 1347, there will be speculation about what it is. It will take until 2017 for science to give us a conclusive answer to the riddle how so many people could die so fast all over Europe, Africa, and Asia in only five years.

Join us on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/TimeGhostHistory

Hosted by: Indy Neidell and Spartacus Olsson

Written by: Indy Neidell and Spartacus Olsson

Directed by: Astrid Deinhard

Executive Producers: Astrid Deinhard, Indy Neidell, Spartacus Olsson, Bodo Rittenauer

Creative Producer: Joram Appel

Post-Production Director: Wieke Kapteijns

Research by: Spartacus Olsson, Indy Neidell, and James Currie

Edited by: Karolina Dołęga

Sound Engineer: Marek Kamiński

Graphic Design: Ryan WeatherbyVisual Sources:

Welcome Images

Mark and Delwen from Flickr: https://www.flickr.com/photos/markand…

Smarteeee from Wiki CommonsIcons from The Noun Project by: arif fajar yulianto, James, Maxim Kulikov, Jejen Juliansyah Nur Agung, Gan Khoon Lay, Alfonso Melolonta Urbán

Laymik, parkjisun, Eucalyp, Adrien Coquet & Mahmure Alp.Music:

“Barrel” – Christian Andersen

“Symphony of the Cold-Blooded” – Christian Andersen

“Potential Redemption” – Max Anson

“Moving to Disturbia” – Experia

“Superior” – Silver Maple

“Please Hear Me Out” – Philip Ayers

“Guilty Shadows 4” – Andreas Jamsheree

“Deadline” – Marten Moses

“Endlessness” – Flouw

“Moving to Disturbia” – ExperiaArchive by Screenocean/Reuters https://www.screenocean.com.

Research Sources:

Quinto Tiberio Angelerio and New Measures for Controlling Plague in 16th-Century Alghero, Sardinia, Raffaella Bianucci, Ole Jørgen Benedictow, Gino Fornaciari, and Valentina Giuffra

“The Path to Pistoia: Urban Hygiene Before the Black Death”, G. Geltner, Past & Present, Volume 246, Issue 1, February 2020, Pages 3–33

Encyclopedia of the Black Death, Joseph Patrick Byrne

“Epidemiological characteristics of an urban plague epidemic in Madagascar, August–November, 2017: an outbreak report”, The Lancet, Rindra Randremanana, PhD *Voahangy Andrianaivoarimanana, PhD Birgit Nikolay, PhD Beza Ramasindrazana, PhD Juliette Paireau, PhD, Quirine Astrid ten Bosch, PhD et al

“Yersinia pestis, the cause of plague, is a recently emerged clone of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis” Mark Achtman, Kerstin Zurth, Giovanna Morelli, Gabriela Torrea, Annie Guiyoule, and Elisabeth Carniel

“Insights into the evolution of Yersinia pestis through whole-genome comparison with Yersinia pseudotuberculosis“, P.S.G. Chain, E. Carniel, F.W. Larimer, J. Lamerdin, P.O. Stoutland, W.M. Regala, A.M. Georgescu, L.M. Vergez, M.L. Land, V.L. Motin, R.R. Brubaker, J. Fowler, J. Hinnebusch, M. Marceau, C. Medigue, M. Simonet, V. Chenal-Francisque, B. Souza, D. Dacheux, J.M. Elliott, A. Derbise, L.J. Hauser, and E. Garcia

“Distinct Clones of Yersinia pestis Caused the Black Death”, Stephanie Haensch, Raffaella Bianucci, Michel Signoli, Minoarisoa Rajerison, Michael Schultz, Sacha Kacki, Marco Vermunt, Darlene A. Weston, Derek Hurst, Mark Achtman, Elisabeth Carniel, Barbara BramantiA TimeGhost chronological documentary produced by OnLion Entertainment GmbH.

From the comments:

TimeGhost History

2 days ago

There is much we can learn from history and as you will see in the next two episodes of our impromptu pandemics series it takes a long time for us to make these learnings. Many of the mistakes made during the outbreak of the Black Death are still an issue as we respond to COVID-19 almost 700 years later. This episode was also a very personal learning experience for us, Indy and Spartacus. Both of us read and studied a lot about the plague when we were younger in the 1980s, Indy even did his BA paper in history on the plague. Back then there was a lot of speculation about what the Black Death actually was (although the general consensus was that it must have been bubonic plague based on the findings made in the 20th century, after the discovery of the Yersinia Pestis bacteria). But that conclusion was a bit problematic — the Black Death was too lethal, spread too fast, and killed people too quickly for bubonic plague. Until we started researching these episodes we hadn’t spent much thought on the topic, so imagine our surprise when we discovered that bacteriologists, epidemiologists, and archeologists had come together to solve the mystery after two chance occurrences of unusual plague outbreaks in 2014 and 2017. To paraphrase Lord Marlborough: if you want to truly learn something about a topic, there’s no better way than to make a video about it.

April 29, 2020

QotD: “Ethical” ways to prevent scientific progress

The stigmatization of science is also jeopardizing the progress of science itself. Today anyone who wants to do research on human beings, even an interview on political opinions or a questionnaire about irregular verbs, must prove to a committee that he or she is not Josef Mengele. Though research subjects obviously must be protected from exploitation and harm, the institutional-review bureaucracy has swollen far beyond this mission. Its critics have pointed out that it has become a menace to free speech, a weapon that fanatics can use to shut up people whose opinions they don’t like, and a red-tape dispenser that bogs down research while failing to protect, and sometimes harming, patients and research subjects. Jonathan Moss, a medical researcher who had developed a new class of drugs and was drafted into chairing the research-review board at the University of Chicago, said in a convocation address, “I ask you to consider three medical miracles we take for granted: X-rays, cardiac catheterization, and general anesthesia. I contend all three would be stillborn if we tried to deliver them in 2005.” The same observation has been made about insulin, burn treatments, and other lifesavers.

The hobbling of research is not just a symptom of bureaucratic mission creep. It is actually rationalized by many bioethicists. These theoreticians think up reasons that informed and consenting adults should be forbidden to take part in treatments that help them and others while harming no one. They use nebulous rubrics like “dignity,” “sacredness,” and “social justice.” They try to sow panic about advances in biomedical research with far-fetched analogies to nuclear weapons and Nazi atrocities, science-fiction dystopias like Brave New World and Gattaca, and freak-show scenarios like armies of cloned Hitlers, people selling their eyeballs on eBay, and warehouses of zombies to supply people with spare organs. The University of Oxford philosopher Julian Savulescu has exposed the low standards of reasoning behind these arguments and has pointed out why “bioethical” obstructionism can be unethical: “To delay by 1 year the development of a treatment that cures a lethal disease that kills 100,000 people per year is to be responsible for the deaths of those 100,000 people, even if you never see them.”

Steven Pinker, “The Intellectual War on Science”, Chronicle of Higher Education, 2018-02-13.

November 16, 2019

History of Space Travel – Kill Devil to V-2 – Extra History – #3

Extra Credits

Published 14 Nov 2019Start your Warframe journey now and prepare to face your personal nemesis, the Kuva Lich — an enemy that only grows stronger with every defeat. Take down this deadly foe, then get ready to take flight in Empyrean! Coming soon! http://bit.ly/EHWarframe

Early flight started as a utopian dream but quickly became the military’s top priority: first as reconnaissance vehicles, and then as weapons in their own right. After WW1, the threat of German aircraft led to the Treaty of Versailles banning Germany from having an airforce at all. But the Germans also found a loophole: rockets didn’t count as an airforce. Enter Werner Von Braun & the V-2 rockets.