Extra Credits

Published on 14 Sep 2019Join us on Patreon! http://bit.ly/EHPatreon

Disease — likely, smallpox or measles — had arrived in the Inca empire, and it was ruthless. Two of the (now dead) Emperor Huayna Capac’s sons, Atahualpa and Huáscar, decided that a civil war over who should be Sapa Inca was perfect to do right now — nevermind the fact that Francisco Pizarro and his conquistadores had just showed up.

September 16, 2019

The Inca Empire – Andean Apocalypse – Extra History – #4

June 9, 2019

History of England – The Devastation of France – Extra History – #3

Extra Credits

Published on 8 Jun 2019From the end of the battle of Crecy, Edward charged on to besiege Calais (successfully), and then returned home. Right about then was when the Black Plague hit Europe head-on. But Edward carried on as king establishing order among his subjects, forming the Knights of the Garter. In France, John le Bel, son of Philip, had learned from the French defeats and was making small victories here and there…

In the middle ages, pillaging and murdering your way across Northern France was clearly considered an appropriate father-son bonding opportunity.

Thanks again to David Crowther for writing AND narrating this series! https://thehistoryofengland.co.uk/pod…

Join us on Patreon! http://bit.ly/EHPatreon

November 18, 2018

New research shows 536AD to have been the true annus horribilis

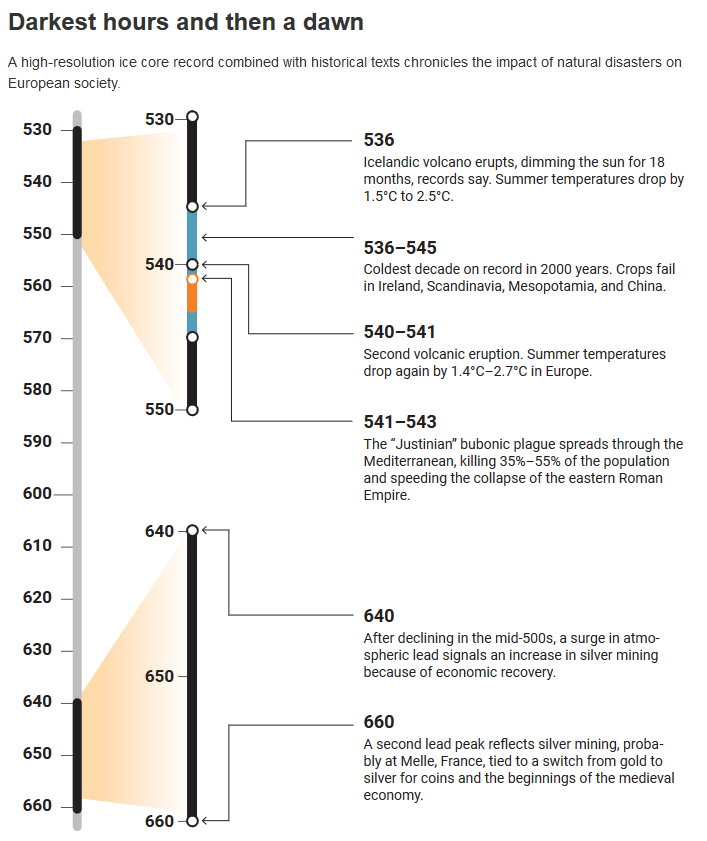

There have been bad years in human history. There have been worse days in human history. But according to a recent study summarized in Science magazine, the worst year in recorded history was 536AD:

Ask medieval historian Michael McCormick what year was the worst to be alive, and he’s got an answer: “536.” Not 1349, when the Black Death wiped out half of Europe. Not 1918, when the flu killed 50 million to 100 million people, mostly young adults. But 536. In Europe, “It was the beginning of one of the worst periods to be alive, if not the worst year,” says McCormick, a historian and archaeologist who chairs the Harvard University Initiative for the Science of the Human Past.

A mysterious fog plunged Europe, the Middle East, and parts of Asia into darkness, day and night — for 18 months. “For the sun gave forth its light without brightness, like the moon, during the whole year,” wrote Byzantine historian Procopius. Temperatures in the summer of 536 fell 1.5°C to 2.5°C, initiating the coldest decade in the past 2300 years. Snow fell that summer in China; crops failed; people starved. The Irish chronicles record “a failure of bread from the years 536–539.” Then, in 541, bubonic plague struck the Roman port of Pelusium, in Egypt. What came to be called the Plague of Justinian spread rapidly, wiping out one-third to one-half of the population of the eastern Roman Empire and hastening its collapse, McCormick says.

Historians have long known that the middle of the sixth century was a dark hour in what used to be called the Dark Ages, but the source of the mysterious clouds has long been a puzzle. Now, an ultraprecise analysis of ice from a Swiss glacier by a team led by McCormick and glaciologist Paul Mayewski at the Climate Change Institute of The University of Maine (UM) in Orono has fingered a culprit. At a workshop at Harvard this week, the team reported that a cataclysmic volcanic eruption in Iceland spewed ash across the Northern Hemisphere early in 536. Two other massive eruptions followed, in 540 and 547. The repeated blows, followed by plague, plunged Europe into economic stagnation that lasted until 640, when another signal in the ice — a spike in airborne lead — marks a resurgence of silver mining, as the team reports in Antiquity this week.

H/T to Blazing Cat Fur for the link.

November 5, 2017

The decline of the (western) Roman empire

Richard Blake considers some of the popular explanations for the slow decline of the Roman empire in the west:

The Empire was an agglomeration of communities which were illiterate to an extent unknown in Western Europe since about 1450. Even most officers in the bureaucracy were at best semi-literate. There was no printing press. Writing materials were very expensive – one sheet of papyrus cost about £100 in today’s money. Cheaper materials were still expensive and were of little use for other than ephemeral use. Central control was usually notional, and the more effective Emperors – Hadrian, Diocletian, et al – were those who spent much of their time touring the Empire to supervise in person.

The economic legislation of the Emperors was largely unenforceable. Some effort was made to enforce the Edict of Maximum Prices. But this appears to have been sporadic, and it lasted only between 301 and 305, when Diocletian abdicated. The Edict’s main effect was to leave a listing of relative prices for economic historians to study 1,500 years later.

As for inflation, it can be doubted how far outside the cities a monetary economy existed. This is not to doubt whether the laws of supply and demand operated, only whether most transactions were not by barter at more or less customary ratios of exchange. This being so, the debasement of the silver coinage would have had less disruptive effect than the silver inflation in Europe of the sixteenth century. Also, the gold coinage was stabilised over a hundred years before the Western military collapse of the fifth century. And the military crisis of the late third century was overcome while the inflation continued.

Nor is there any evidence that people left the cities in large numbers for the countryside. The truth seems to be that the Roman Empire was afflicted, from the middle of the second century, by a series of epidemic plagues, possibly brought on by global cooling, that sent populations into a decline that continued until about the eighth century. The cities shrank not because their inhabitants left them, but because they died. So far as they were enforced, the Imperial responses to population decline made things worse, but were not the ultimate cause of decline. Where population decline was less severe, there was no economic decline. Whenever the decline went into temporary reverse – as it may have in the fifth century in the East – economic activity recovered.

Von Mises is right that the barbarian invasions were not catastrophic floods that destroyed everything in their path. They were incursions by small bands. What made them irreversible was that they took place in the West into a demographic vacuum that would have existed regardless of what laws the Emperors made.

March 15, 2016

Justinian & Theodora – Lies 2 – Extra History

Published on 5 Mar 2016

By the time Narses was sent to join him Italy, Belisarius had been away from Constantinople for a very long time. The royal family wasn’t sure if they could still trust him, or if his repeated victories had gone to his head, so they sent Narses (who had been in Constantinople and earned their trust) to keep an eye on him. But this laid the groundwork for disputes that would unravel the military effort there. John looked down on the “barbarian” Ostrogoths and did not consider them a threat, so he viewed the war in Italy as a political battlefield between his friend Narses and his commander Belisarius. Although Procopius defends John’s courage and capability as a cavalry commander, John did not see the bigger picture in Italy and his actions interfered with Belisarius’s overall strategy even though Narses and his family connection to the previous emperor helped keep him safe from repercussions. Belisarius wound up doing the same thing when he refused Justinian’s orders to leave Italy immediately. And in the end, the arrival of the plague – Bubonic Plague, the Black Death – interfered with all their plans. Although we believe Theodora’s actions helped hold the empire together, historians like Procopius take a much darker view: he thought she went power-mad and ruined everything. It’s also worth taking a moment to point out that Theodora was a miaphysite Christian, not a monophysite as we described her in this series. We’ll clarify the difference in a future series on Early Christian Heresies, but for right now we decided to simplify. And there was one thing we left out of this series, a story we love about how Justinian succeeded (where so many had failed) in getting silk worms out of China by bribing monks to smuggle silk worm eggs away in their canes. He helped found a silk industry that brought a lot of money to the empire, and helped it survive longer than it might have otherwise.

March 3, 2016

Theodora – X: This is My Empire – Extra History

Published on 13 Feb 2016

The first recorded outbreak of the Bubonic Plague occurred in Pelusium, an isolated town in the Egyptian province, but soon it moved on to Alexandria. Alexandria was the breadbasket of the Empire, and ships carrying grain (and plague-bearing rats) spread across the Empire. The Plague reached Constantinople to disastrous effect: 25% of the population died. Justinian set up a burial office but even they couldnt keep up with the demand. When they ran out of burial land, they started piling corpses into ships and setting them afloat; they even packed them into the guard towers along the wall. So few people survived that when word got out that Justinian had contracted the plague, hope seemed lost… until Theodora stepped up. She had always been a force within the Empire, Justinian’s co-regent, and now she used that power to fight off the plots against him and keep the Empire together. She dealt ruthlessly with anyone who threatened them, and since many people wanted Belisarius installed on the throne as Justinian’s heir, she recalled him and pushed him out of power. She managed to keep the Empire from disintegrating into Civil War and became the symbol of hope and perserverance for a sorely demoralized city. And then, miraculously, Justinian pulled through.