I was raised as a Methodist and I was a believer until the age of eleven. Then I lost faith and became an annoying atheist for decades. In recent years I’ve come to see religion as a valid user interface to reality. The so-called “truth” of the universe is irrelevant because our tiny brains aren’t equipped to understand it anyway.

Our human understanding of reality is like describing an elephant to a space alien by saying an elephant is grey. That is not nearly enough detail. And you have no way to know if the alien perceives color the same way you do. After enduring your inadequate explanation of the elephant, the alien would understand as much about elephants as humans understand about reality.

In the software world, user interfaces keep human perceptions comfortably away from the underlying reality of zeroes and ones that would be incomprehensible to most of us. And the zeroes and ones keep us away from the underlying reality of the chip architecture. And that begs a further question: What the heck is an electron and why does it do what it does? And so on. We use software, but we don’t truly understand it at any deep level. We only know what the software is doing for us at the moment.

Religion is similar to software, and it doesn’t matter which religion you pick. What matters is that the user interface of religious practice “works” in some sense. The same is true if you are a non-believer and your filter on life is science alone. What matters to you is that your worldview works in some consistent fashion.

Scott Adams, “The User Interface to Reality”, The Scott Adams Blog, 2014-07-15.

June 25, 2015

QotD: Religion as a user interface for reality

June 22, 2015

“Because economic growth is a dead end. The greens present the only way out”

J.R. Ireland pokes fun at the UK Green Party manifesto for the last general election:

All around the world our cultures might be different, our languages might be different, and we may think differently and act differently, but there is one fact which is true in every country on the face of planet Earth: The local Green Party will always be completely and irredeemably insane. From Australian pundit Tim Blair I’ve been made aware of the manifesto for the United Kingdom Green Party, a ludicrous amalgamation of wishful thinking, happy talk, and a total unwillingness to consider the unintended consequences of their proposed policies. From the absolutely bugfuck bonkers Youth Manifesto:

Because economic growth is a dead end. The greens present the only way out.

Vote Green because they’re the only party courageous enough to promise voters that they will end economic growth. If there’s one way to win elections, it’s to tell the good people of Britain that you promise them an eternity of poverty and absolutely guarantee they will never get any richer.

Furthermore:

We would introduce the right to vote at 16 because we believe that young people should have a say, as proven by the Scottish Independence Referendum in 2014.

Indeed. Who wouldn’t want to have their country governed by the preferred candidates of middle teenagers? Why, the average 16 year old is so incredibly knowledgeable about the world and completely understands such complex topics as economics, immigration, and that hot chick Kristy’s red panties that he accidentally saw when she was uncrossing her legs in homeroom. With those sorts of brilliant minds choosing the leaders of the future, what could possibly go wrong?

[…]

But the real crazy, the high-end crazy, the crazy with a ribbon on top was saved not for their youth manifesto but for the manifesto allegedly meant for the big boys and girls who have hit puberty biologically, even if they never quite made it intellectually. The Green Party, you see, promises to give you infinite happiness without any negative consequences whatsoever:

Imagine having a secure, fulfilling and decently paid job, knowing that you are working to live and not living to work. Imagine coming home to an affordable flat or house, and being valued for your contribution and character, not for how much you earn. Imagine knowing that you and your friends are part of an economy that works with the planet rather than against it. Imagine food banks going out of business. Imagine the end of poverty and deprivation. The key to all this is to put the economy at the service of people and planet rather than the other way round. That’s what the Green Party will do.

Imagine there’s no countries. It isn’t hard to do. Nothing to kill or die for and no religion too.

Indeed. Now if only John Lennon lyrics were a governing philosophy, by Jove the Greens might be onto something! Unfortunately for the Green Party, our actions often have consequences we could not have foreseen and, unsurprisingly, if you declare war on business with massive taxes, anti-trade legislation and the nationalization of banks and the housing industry, it’s awfully difficult to ‘end poverty and deprivation’ since you’ve completely eliminated the way by which people have the opportunity to lift themselves up. But don’t worry — the Greens will just sprinkle some fairy dust around and negative consequences will magically be done away with! Supply and demand is simply a filthy conspiracy perpetuated by the bourgeoisie!

June 4, 2015

QotD: The debt we owe to ancient Greece

What more to say? Well, I could say that I am jealous of Jack’s choice of period. My choice of early Byzantium is a good one. Contrary to the general view, this was an age of heroism and genius. The fight the Byzantines put up against the barbarians and Persians and Moslems saved Western civilisation. There are few stories more inspiring than the defeat of the Arabs outside the very walls of Constantinople in 678 and 717. At the same time, nothing compares with what the Athenians achieved a thousand years earlier.

Forget the Egyptians and the Jews. Forget what we are told about the ancient Indians and Chinese. Forget even the Romans. Between about 600 and 300 BC, the Greeks of Athens and some of the cities of what is now the Turkish coast were easily the most remarkable people who ever lived. They gave us virtually all our philosophy, and the foundation of all our sciences. Their historians were the finest. Their poetry was second only to that of Homer – and it was they who put together all that we have of Homer. They gave us ideals of beauty, the fading of which has always been a warning sign of decadence; and they gave us the technical means of recording that beauty. They had no examples to imitate. They did everything entirely by themselves. In a world that had always been at the midnight point of barbarism and superstition, they went off like a flashbulb; and everything good in our own world is part of their afterglow. Every renaissance and enlightenment we have had since then has begun with a rediscovery of the ancient Greeks. Modern chauvinists may argue whether England or France or Germany has given more to the world. In truth, none of us is fit to kiss the dust on which the ancient Greeks walked.

Richard Blake, “Review of Jack England, Sword of Marathon“, RichardBlake.me.uk, 2013.

May 8, 2015

QotD: The barbarians in our midst

… possibly the most dangerous barbarians live in the West. These, by being born there, assume they are Westerners by inheritance or osmosis. They also regard Western civilization as “found”, its goodies a stash waiting to be used or distributed. Nor do they trouble themselves as to its provenance, for there has always been plenty more where the stash came from.

For these barbarians Western civilization and its associated quest for God or Truth are a bothersome impediment, a “white man’s culture”, a hundred year old relic ideology nobody bothers with, some irksomely judgmental superfluity that gets in the way of fun and spreading the fruits to arrivals at the border and various victim groups.

For the barbarian the only reality is appearances. Cargo cultists, for instance, believe that function comes from form. If they build something which resembles an airport then gift giving airplanes will arrive there to bring goodies. The 21st century barbarian completely lacks the attitude of Roger Bacon, who lived in the 13th century. Bacon knew that the truth was not a “white man’s” culture — in fact in his day nearly all learning came from the East — but believed the truth was nature’s culture; baked into reality; another word for what used to be called God. Of barbarian ignorance Bacon wrote:

Many secrets of art and nature are thought by the unlearned to be magical. … The empire of man over things depends wholly on the arts and sciences. For we cannot command nature except by obeying her.

In today’s post-Western environment, we’ve forgotten Bacon’s adage.

Richard Fernandez, “Sword and Sorcery”, Belmont Club, 2014-06-23.

March 25, 2015

Millennials, philosophical malaise, and the moving target of “adulthood”

In Spiked, Tom Slater reviews a recent book by Susan Neiman, calling it “the philosophical kick up the arse my generation so desperately needs”:

Why Grow Up?, the latest book by American philosopher and essayist Susan Neiman, begins with a slyly subversive statement: ‘Being grown up is itself an ideal.’ In Britain today, this couldn’t seem further from the truth. Today, we’re told, is the worst time to be reaching adulthood. With economic strife, rising house prices, tuition fees and widespread youth unemployment weighing on Generation Y’s pasty back, coming of age merely means coming to the realisation that debt, destitution and living with mum and dad into your thirties is your inevitable inheritance. And that’s hardly an adulthood worth having.

The question this book seeks to answer is why growing up seems such a grim prospect today. From the off, Neiman dispenses with the sort of neuroscientific apologism that we’ve become accustomed to in recent years. Within the current, fatalistic climate, adulthood has been defined down. The Science now says that adolescence stretches into your mid-twenties. But, as Neiman observes in her introduction, there’s nothing scientific about growing up. The lines between childhood, adolescence and adulthood are mutable, and have changed over time. Less than a century ago, childhood, as a time of pampered play and dependence, lasted barely a few years for the vast majority of the population. And when most young people were out of school and married by the end of their teens, adolescence – the rebellious grace period between Tonka trucks and 2.4 children – didn’t even exist.

Instead, Neiman presents adulthood as a process of coming to terms with the circumstances you find yourself in and then committing to changing them – reconciling the ‘is’ and the ‘ought’. She situates this in the history of Enlightenment thought, in which the doomy realism of Hume clashed with the rugged idealism of Rousseau. ‘It would take Kant’, Neiman writes, ‘to appreciate the fact that we must take both seriously – if we are ever to arrive at an adulthood we need not merely acquiesce in but actively claim as [our] own’.

March 7, 2015

QotD: The “true meaning” of Starship Troopers

The central theme is expanded in many ways and many sub-propositions consistent with or corollary to the main one are shown: (a) that nothing worth having is ever free; it must be paid for; (b) that authority always carries with it responsibility, even if a man tries to refuse it; (c) that “natural rights” are not God-given but must be earned; (d) that, despite all H-bombs, biological warfare, push-buttons, ICBMs, or other Buck Rogers miracle weapons, victory in war is never cheap but must be purchased with the blood of heroes; (e) that human beings are not potatoes, not actuarial tables, but that each one is unique and precious … [sic] and that the strayed lamb is as precious as the ninety-and-nine in the fold; (f) that a man’s noblest act is to die for his fellow man, that such death is not suicidal, not wasted, but is the highest and most human form of survival behaviour.

Robert A. Heinlein, letter to Alice Dalgliesh 1959-02-03 (but marked “Never Sent”), quoted in William H. Patterson Jr., Robert A. Heinlein, In Dialogue with His Century Volume 2: The Man Who Learned Better, 2014).

February 22, 2015

On a lighter note…

Scott Alexander rings the changes on the “x walks into a bar” joke … but it’s not a bar, it’s a coffee shop:

Gottfried Leibniz goes up to the counter and orders a muffin. The barista says he’s lucky since there is only one muffin left. Isaac Newton shoves his way up to the counter, saying Leibniz cut in line and he was first. Leibniz insists that he was first. The two of them come to blows.

* * *

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel goes up to the counter and gives a tremendously long custom order in German, specifying exactly how much of each sort of syrup he wants, various espresso shots, cream in exactly the right pattern, and a bunch of toppings, all added in a specific order at a specific temperature. The barista can’t follow him, so just gives up and hands him a small plain coffee. He walks away. The people behind him in line are very impressed with his apparent expertise, and they all order the same thing Hegel got. The barista gives each of them a small plain coffee, and they all remark on how delicious it tastes and what a remarkable coffee connoisseur that Hegel is. “The Hegel” becomes a new Starbucks special and is wildly popular for the next seventy years.* * *

Adam Smith goes up to the counter. “I’ll have a muffin,” he says. “Sorry,” says the barista, “but those two are fighting over the last muffin.” She points to Leibniz and Newton, who are still beating each other up. “I’ll pay $2 more than the sticker price, and you can keep the extra,” says Smith. The barista hands him the muffin.* * *

Ludwig Wittgenstein goes up to the counter. “I’ll have a small toffee mocha,” he says. “We don’t have small,” says the barista. “Then what sizes do you have?” “Just tall, grande, and venti.” “Then doesn’t that make ‘tall’ a ‘small’?” “We call it tall,” says the barista. Wittgenstein pounds his fist on the counter. “Tall has no meaning separate from the way it is used! You are just playing meaningless language games!” He storms out in a huff.* * *

Ayn Rand goes up to the counter. “What do you want?” asks the barista. “Exactly the relevant question. As a rational human being, it is my desires that are paramount. Since as a reasoning animal I have the power to choose, and since I am not bound by any demand to subordinate my desires to that of an outside party who wishes to use force or guilt to make me sacrifice my values to their values or to the values of some purely hypothetical collective, it is what I want that is imperative in this transaction. However, since I am dealing with you, and you are also a rational human being, under capitalism we have an opportunity to mutually satisfy our values in a way that leaves both of us richer and more fully human. You participate in the project of affirming my values by providing me with the coffee I want, and by paying you I am not only incentivizing you for the transaction, but giving you a chance to excel as a human being in the field of producing coffee. You do not produce the coffee because I am demanding it, or because I will use force against you if you do not, but because it most thoroughly represents your own values, particularly the value of creation. You would not make this coffee for me if it did not serve you in some way, and therefore by satisfying my desires you also reaffirm yourself. Insofar as you make inferior coffee, I will reject it and you will go bankrupt, but insofar as your coffee is truly excellent, a reflection of the excellence in your own soul and your achievement as a rationalist being, it will attract more people to your store, you will gain wealth, and you will be able to use that wealth further in pursuit of excellence as you, rather than some bureaucracy or collective, understand it. That is what it truly means to be a superior human.” “Okay, but what do you want?” asks the barista. “Really I just wanted to give that speech,” Rand says, and leaves.

* * *

Voltaire goes up to the counter and orders an espresso. He takes it and goes to his seat. The barista politely reminds him he has not yet paid. Voltaire stays seated, saying “I believe in freedom of espresso.”* * *

Thomas Malthus goes up to the counter and orders a muffin. The barista tells him somebody just took the last one. Malthus grumbles that the Starbucks is getting too crowded and there’s never enough food for everybody.

January 30, 2015

What can Plato’s Cave tell us about basic economics?

Over at Ace of Spades H.Q., Monty takes us back to Philosophy 101 to show the economic version of Plato’s famous story:

If you had occasion to take a Philosophy 101 course in college, you may remember the allegory of Plato’s cave. Plato meant it as a discussion of what “reality” is — whether it is an absolute thing, and whether humans can experience “reality” in its totality or if we are limited only to what we can experience and measure. The idea is that what we can sense and measure is only a subset of a larger reality that we cannot perceive directly.

I’ve long thought that this allegory works quite well for economics in many ways, especially as it pertains to concepts of money and wealth.

Take a dollar out out of your pocket and look at it. What is it? It’s many things, actually: it is money, so it must be a store of wealth, a unit of account, and a medium of exchange; it is a manufactured good, intended by its manufacturer to be used as currency; it is a work of engravers’ art; it is a complex piece of technology (especially modern bills with the various anti-counterfeiting countermeasures); it is a carrier for the oils, dirt, and germs of the people who have handled it; and so on.

You can think of money as a special kind of battery, only instead of storing electricity, it stores up economic value which can be expended at a later time. And just as a battery can store energy but not create it, money can store value but not create it.

It turns out that this dollar bill is a pretty complex object, all things considered. And yet it isn’t a “real” thing in the sense Plato was speaking of. Whatever else it may be, a dollar is not in itself valuable; it is rather a signifier of a real thing we cannot see directly. A unit of money — whether a dollar, a franc, a pound, or a quatloo — is only “real” insofar as it signifies some existing value in the economy. (We can think of some value as being latent as opposed to realized, as it often is with investments. We invest in expectation of value being created and providing some kind of return on the investment. No value appears spontaneously out of the void. The invested capital is based on already-existing assets; a return is only realized if the endeavor creates additional value. Interest income or dividends don’t just magically materialize — interest income is your share of the value added and payment for the time-value of the money you invested. Nothing comes from nothing, as Parmenides reminds us.)

That dollar you hold in your hand is the shadow cast by something of value in the world of real things.*

[…]

* One way in which the Plato’s Cave allegory doesn’t work well in the monetary sense is when considering an essential property of money: fungibility. For money to be money, it must be fungible — that is, a dollar bill is exactly like any other dollar bill in terms of how it behaves in a monetary sense. I can buy a candy bar with any dollar, not just one specific dollar. The Plato’s Cave allegory draws a 1-to-1 linkage between the “real” object we cannot perceive and the shadow we can perceive, but with money it is more like a probabilistic wavefront that only collapses when you spend the dollar.

This means that, in the economic sense, our “shadow” of a real world good or service is not a particular dollar but any dollar.

January 15, 2015

January 1, 2015

J.R.R. Tolkien – confessed anarchist

In The Federalist, Jonathan Witt and Jay W. Richards wonder if the Shire is a hippie paradise:

“The Battle of the Five Armies,” the final installment of The Hobbit film trilogy, opened last week, and online boards are buzzing with discussions of Peter Jackson’s casting decisions, his use or overuse of computer-generated imagery and what Middle-Earth’s creator, J.R.R. Tolkien, would have thought of the films. Geeky questions, to be sure, but for those who follow both Tolkien and politics, we suggest a still geekier line of inquiry: How would Tolkien vote? That is, what kind of political vision did the Oxford professor carry into his novels?

His wildly popular novels have, after all, shaped generations of followers, and are shot through with valuable insights about man and government that might not be obvious to a casual reader or fan of the movie versions. Tolkien’s political insights, moreover, are in danger of being lost and forgotten in the capitols of the West. Here, in other words, is a vein worth mining.

[…]

An early hint of this can be found in the beloved homeland of the hobbits, the Shire. Her pastoral villages have no department of unmotorized vehicles, no internal revenue service, no government official telling people who may and may not have laying hens in their backyards, no government schools lining up hobbit children in geometric rows to teach regimented behavior and groupthink, no government-controlled currency, and no political institution even capable of collecting tariffs on foreign goods.

“The Shire at this time had hardly any ‘government,’” we eventually learn. “Families for the most part managed their own affairs.”

Significantly, Tolkien once described himself as a hobbit “in all but size,” commenting in the same letter that his “political opinions lean more and more to Anarchy (philosophically understood, meaning abolition of control, not whiskered men with bombs).” As he explained, “The most improper job of any man, even saints, is bossing other men. Not one in a million is fit for it, and least of all those who seek the opportunity.”

In the Shire, Tolkien created a society after his own heart, one marked by minimal government, private charity, and a commitment to property rights and the rule of law.

This isn’t to say the Shire is without problems. Near the end of The Lord of the Rings, Frodo returns home after a quest to destroy a corrupting ring of absolute power. To his dismay, a gang of bossy outsiders has infiltrated the Shire, “gatherers and sharers … going around counting and measuring and taking off to storage,” supposedly “for fair distribution,” but what becomes of most of it is anyone’s guess.

Ugly new buildings are being thrown up, beautiful hobbit homes spoiled. And for all the effort to “spread the wealth around” (to borrow a phrase from our current president), the only thing that seems to be spreading is the gatherers’ power. It’s a critique of aesthetically impoverished urban development, to be sure. But conservatives and progressives alike also have seen in it a pointed critique of the modern, hyper-regulated nanny state.

As Hal Colebatch put it in the Tolkien Encyclopedia, the Shire’s joyless regime of bureaucratic rules and suffocating redistribution “owed much to the drabness, bleakness and bureaucratic regulation of postwar Britain under the Attlee labor Government.”

December 15, 2014

QotD: The “purity” of Marx

You or I, upon hearing that the plan is to get rid of all government and just have people share all property in common, might ask questions like “But what if someone wants more than their share?” Marx had no interest in that question, because he believed that there was no such thing as human nature, and things like “People sometimes want more than their shares of things” are contingent upon material relations and modes of production, most notably capitalism. If you get rid of capitalism, human beings change completely, such that “wanting more than your share” is no more likely than growing a third arm.

A lot of the liberals I know try to distance themselves from people like Stalin by saying that Marx had a pure original doctrine that they corrupted. But I am finding myself much more sympathetic to the dictators and secret police. They may not have been very nice people, but they were, in a sense, operating in Near Mode. They couldn’t just tell themselves “After the Revolution, no one is going to demand more than their share,” because their philosophies were shaped by the experience of having their subordinates come up to them and say “Boss, that Revolution went great, but now someone’s demanding more than their share, what should we do?” Their systems seem to be part of the unavoidable collision of Marxist doctrine with reality. It’s possible that there are other, better ways to deal with that collision, but “returning to the purity of Marx” doesn’t seem like a workable option.

Scott Alexander, “Book Review: Singer on Marx”, Slate Star Codex, 2014-09-13.

September 16, 2014

QotD: The real value of work

People without meaningful work and copious free time don’t write symphonies or create great works of art. They don’t live a life of the mind. They drink too much, or get in fights, or watch a lot of internet porn, or commit crimes. They don’t contribute to the economy or culture, as a rule. They just…exist. And it goes on like that, sometimes for generations.

Labor is the fate of all humankind. Always has been. We work to live. Work gives shape and meaning to our lives. It’s not just the income we derive from it; it’s the knowledge that we are able to function as adults in the wider world, and provide for ourselves and our families. It’s feeling the satisfaction of having contributed something to the maintenance of civilization, even if it means we haul trash away or keep the grass mowed. It’s all honorable work, necessary work, and not something to be ashamed of.

It’s not an outrage, it’s just the way things are. To try and embitter people about that, to make them feel that the natural order of things is unfair, is just to do an enormous amount of harm to the very people you’re claiming to want to help.

Monty, “We’re now living in a post-labor Utopia. Have you heard about this?”, Ace of Spades HQ, 2014-02-06

July 11, 2014

July 3, 2014

Jeremy Bentham’s “secret” writings

In the Guardian, Faramerz Dabhoiwala reviews a recent “discovery” that Jeremy Bentham, far from being an innocent about sexual matters (as portrayed by his disciple John Stuart Mill among others), had thought deeply on the topic and had written much. After his death, these writings were ignored for fear that they would discredit his wider body of work.

Bodily passion was not just a part of Bentham’s life: it was fundamental to his thought. After all, the maximisation of pleasure was the central aim of utilitarian ethics. In place of the traditional Christian stress on bodily restraint and discipline, Bentham sought, like many other 18th-century philosophers, to promote the benefits of economic consumption, the enjoyment of worldly appetites and the liberty of natural passions. This modern, enlightened view of the purpose of life spawned a revolution in sexual attitudes, and no European scholar of the time pursued its implications as thoroughly as Bentham. To think about sex, he noted in 1785, was to consider “the greatest, and perhaps the only real pleasures of mankind”: it must therefore be “the subject of greatest interest to mortal men”. Throughout his adult life, from the 1770s to the 1820s, he returned again and again to the topic. Over many hundreds of pages of private notes and treatises, he tried to strip away all the irrational and religious prohibitions that surrounded sexual activity.

Of all enjoyments, Bentham reasoned, sex was the most universal, the most easily accessible, the most intense, and the most copious — nothing was more conducive to happiness. An “all-comprehensive liberty for all modes of sexual gratification” would therefore be a huge, permanent benefit to humankind: if consenting adults were freed to do whatever they liked with their own bodies, “what calculation shall compute the aggregate mass of pleasure that may be brought into existence?”

The main impetus for Bentham’s obsession with sexual freedom was his society’s harsh persecution of homosexual men. Since about 1700, the increasing permissiveness towards what was seen as “natural” sex had led to a sharpened abhorrence across the western world of supposedly “unnatural” acts. Throughout Bentham’s lifetime, homosexuals were regularly executed in England, or had their lives ruined by the pillory, exile or public disgrace. He was appalled at this horrible prejudice. Sodomy, he argued, was not just harmless but evidently pleasurable to its participants. The mere fact that the custom was abhorrent to the majority of the community no more justified the persecution of sodomites than it did the killing of Jews, heretics, smokers, or people who ate oysters — “to destroy a man there should certainly be some better reason than mere dislike to his Taste, let that dislike be ever so strong”.

Though ultimately he never published his detailed arguments for sexual liberty for fear of the odium they would bring on his general philosophy, Bentham felt compelled to think them through in detail, to write about them repeatedly and to discuss them with his acquaintances. In one surviving letter to a friend, he joked that his rereading of the Bible had finally revealed that the sin for which God had punished the inhabitants of Sodom and Gomorrah was not in fact buggery, but the taking of snuff. He and his secretary had consequently taken a solemn oath to hide their snuff-pouches and nevermore to indulge “that anti-Christian and really unnatural practice” in front of one another. Meanwhile, they were now both happily free to enjoy “the liberty of taking in the churchyard or in the market place, or in any more or less public or retired spot with Man, Woman or Beast, the amusement till now supposed to be so unrighteous, but now discovered to be a matter of indifference”. Among those with whom Bentham discussed his arguments for sexual toleration were such influential thinkers and activists as William Godwin, Francis Place and James Mill (John Stuart Mill’s father). Bentham’s ultimate hope, “for the sake of the interests of humanity”, was that his private elaboration and advocacy of these views might contribute to their eventual free discussion and general acceptance. “At any rate,” he once explained, even if his writings could not be published in his own lifetime, “when I am dead mankind will be the better for it”.

June 26, 2014

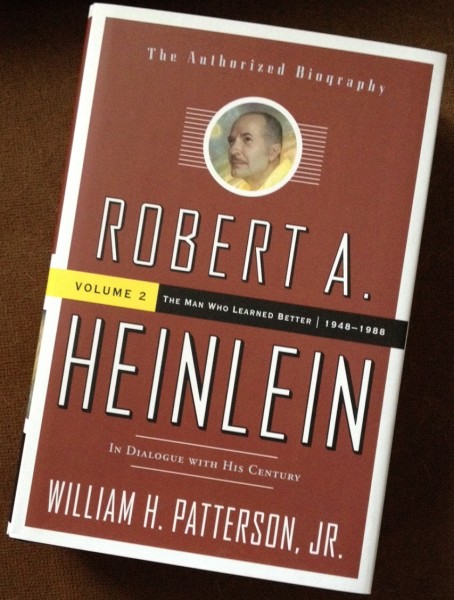

The second volume of Patterson’s biography of Robert Heinlein

In the Washington Post, Michael Dirda reviews the second (and final) volume of William Patterson’s Robert A. Heinlein: In Dialogue With His Century.

In the Washington Post, Michael Dirda reviews the second (and final) volume of William Patterson’s Robert A. Heinlein: In Dialogue With His Century.

Robert Anson Heinlein (1907-1988) possessed an astonishing gift for fast-paced narrative, an exceptionally engaging voice and a willingness to boldly go where no writer had gone before. In “— All You Zombies—” a transgendered time traveler impregnates his younger self and thus becomes his own father and mother. The protagonist of Tunnel in the Sky is black, and the action contains hints of interracial sex, not the usual thing in a 1955 young adult book. While Starship Troopers (1959) championed the military virtues of service and sacrifice, Stranger in a Strange Land (1961) became a bible for the flower generation, blurring sex and religion and launching the vogue word “grok.”

Heinlein’s finest work in the short story was produced in the late 1930s and early ’40s, mainly for the legendary editor of Astounding, John W. Campbell. But by 1948, when this volume opens, “The Roads Must Roll,” “By His Bootstraps, “Gulf” and “Requiem” are behind him. The onetime pulp writer has broken into the Saturday Evening Post and Boy’s Life, married his third (and last) wife, Virginia, and settled in Colorado Springs, where he designs and builds a state-of-the-art automated house. Apart from his occasional involvement with Hollywood, as in scripting Destination Moon, he will devote the rest of his career mainly to novels.

[…]

Like his fascinating but long-winded first volume, the second half of Patterson’s biography is difficult to judge fairly. Packed with facts both trivial and significant, relying heavily on the possibly skewed memories of the author’s widow, and utterly reverent throughout, volume two emphasizes Heinlein the husband, traveler, independent businessman and political activist. Above all, the book celebrates the intense civilization of two that Heinlein and his wife created. There is almost nothing in the way of literary comment or criticism.

Though Heinlein can do no wrong in his biographer’s eyes, if you use yours to look in Patterson’s voluminous endnotes, you will occasionally find confirmation that the writer could be casually cruel as well as admirably generous, at once true to his beliefs and unpleasantly narrow-minded and inflexible about them. Today we would call Heinlein’s convictions libertarian, his personal philosophy grounded in absolute freedom, individual responsibility and an almost religiously inflected patriotism. Heinlein could thus be a confirmed nudist and member of several Sunshine Clubs as well as a grass-roots Barry Goldwater Republican.

For the record, I loved this volume even more than I loved the first one. But Dirda’s comments are fair: Patterson worked hard to present Heinlein in as positive a light as possible, so it’s not unreasonable to suspect that the great man’s character quirks could make him difficult and awkward to deal with at times (to be kind). In the last post, I talked about the adolescent Heinlein as being “probably a pretty toxic individual” and that aspect of his character can still be discerned in the recounting of his later years.