Practical Engineering

Published Jun 18, 2024Why Fern Hollow Bridge collapsed.

This is a crazy case study of how common sense can fall through the cracks of strained budgets and rigid oversight from federal, state, and city staff. And the lessons that came out of it aren’t just relevant to people who work on bridges. It’s a story of how numerous small mistakes by individuals can collectively lead to a tragedy.

(more…)

September 29, 2024

This Bridge Should Have Been Closed Years Before It Collapsed

August 11, 2024

Tears are still a powerful weapon for female politicians

Janice Fiamengo on the tactic available to — and resorted to frequently — only females in politics, turning on the waterworks to generate sympathy and support:

Recently, a friend sent me a news article that illustrates, in small, the world of Anglophone politics, in which notions of what is owed to women, who are understood to be far more sensitive and fragile than men, operate alongside stern interdictions against stating that women are in any manner unsuited for strenuous, high stress roles.

Last week, an ABC News report detailed years-old allegations against a former aide to Josh Shapiro, the Governor of Pennsylvania who was, at the time of the article, one of Kamala Harris’s touted VP possibilities (she has since chosen Tim Walz, Governor of Minnesota). Shapiro’s former staffer, Mike Vereb, who resigned in 2023 over a sexual harassment allegation, is said to have brought a woman to tears in 2018 with threats made over the phone (“You will be less than nothing by the time Josh and I get done with you”, he is alleged to have said).

The woman, who runs an advocacy group, was left “weeping and in shock standing alone in a parking lot”. She did not report the alleged incident until she heard about the aide’s resignation five years later.

[…]

With the staffer long gone from Shapiro’s administration, the story had legs only because it was about a man who made a woman cry.

The problem is that women do cry rather frequently in politics. And complain. And perform their sensitivity to criticisms, monikers, crude jokes, the faux terror of J6, and bantering innuendo. Far too often such women make politics about them as women and about the trouble men allegedly cause them.

Such was the case with Australian Prime Minister Julia Gillard, who earned plaudits from feminists in 2012 for a fury-filled speech in the House of Representatives about sexism, in which she accused the opposition leader of misogyny for a number of statements he’d made that were not at all misogynistic, including that women were likely under-represented in Australian institutions of power because men were “more adapted to exercise authority”. Gillard also said she was “personally offended” (a more serious state of affairs, one assumes, than simply being “offended”) by the opposition leader’s contention that abortion was “the easy way out”. (The text of her speech is here.) “Julia Gillard’s Attack on Sexism Hailed as Turning Point for Australian Women” ran one enthusiastic headline. And perhaps it was, signaling the point at which women in politics stopped thinking they should accommodate themselves to the rigors of public life, and decided that politicians must instead accommodate themselves to the rigors of women’s demands.

Even seemingly tough-as-nails Hillary Clinton has been allowed to go from interview to interview revisiting the now years-old indignity of her election loss in 2016, like a once-popular debutante who can’t believe she didn’t make the cheerleading squad. No man would ever be given such a prolonged pity party. Having contended for years that it was misogyny that prevented her from beating Donald Trump, she more recently pointed her finger at female voters’ failures of confidence: “They left me [in the final days of the campaign] because they just couldn’t take a risk on me, because as a woman, I’m supposed to be perfect“, she explained in May, 2024. No one seems to have informed Clinton that nothing reveals her crippling unsuitability for leadership than her embarrassing refusal to stop feeling sorry for herself.

And she is, alas, far from unique. Nicola Sturgeon, former First Minister of Scotland, sat and sobbed at last winter’s Covid-19 Inquiry in Edinburgh, deflecting critical questions about her government’s actions during the pandemic by proclaiming that she would carry the impact of them for as long as she lived. Forget the thousands of Scots who suffered or even died because of those decisions: the woman in charge was the one in need of compassion. Sturgeon had previously made a career of complaining about the sexism that allegedly put obstacles in the way of female politicians. Her focus on her own emotional discomfort at the Covid inquiry did more than any naysayers to indict the feminine style. How refreshing if either of these women could simply accept responsibility for their failures.

April 15, 2024

The MOST INCOMPETENT Railroad You’ve Ever Seen!

Southern Plains Railfan

Published Jan 6, 2024In today’s video, we recount the time Penn Central let nearly all of Maine’s potato harvest rot in Selkirk yard; ruining thousands of lives and nearly taking down other railroads in the process.

Merch Shop: http://okieprint.com/SPR/shop/home

October 22, 2023

A lawyer in “deep blue” Pennsylvania discovers that elected bodies don’t have to listen to the voters

Chris Bray on the details of a case from Pennsylvania where an active and involved parent tried to get answers from the elected school board on how they justified imposing masking requirements without a shred of legal power to do so:

In December of 2021, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court ruled that officials in that state had implemented mask mandates that they had no legal authority to impose. The decision in Corman v. Beam is not written in stirring language, and makes no bold declarations about truth, freedom, and the American way; it’s a workmanlike examination of statutory language, quite dull to read. Test me on that characterization, if you want. But the court concluded, importantly, that the mandate had been invalid ab initio — not from the moment the court struck it down, but rather from the moment it was issued. Mask mandates had never been enforceable in Pennsylvania.

In an affluent, deep blue community in the Philadelphia suburbs, a lawyer and parent named Chad Williams took the ruling as vindication. With four children in the local schools, he’d been telling school officials — clearly and often — that they had no legal authority to require masks on campus. To say that they hadn’t listened would be an understatement.

In August of 2020, during a Zoom meeting to decide on in-person school for the soon-to-begin school year, the nine-member Unionville-Chadds Ford school board muted Williams when he asked about the legal basis for the choice.

Repeating the performance, school board members cut the microphones and walked out of one of their own subsequent meetings, in August of 2021, to avoid listening to Williams when he didn’t stop speaking at the three-minute mark during their public comment session. Other parents concerned about forced masking for children received a similarly warm reception. The school board voted unanimously that same night to again impose a mask mandate on their campuses for the new school year.

For Williams, the repeated experience was a shock. He was an experienced lawyer, a parent, an established member of the community, and a volunteer coach at the high school — and he couldn’t get anyone to listen to a reasonable question. He asked his school board to explain the legal basis for a new policy, and “the school board president just cut me off.” Officials were acting in lockstep, without apparent authority, and refusing to explain their choices. “They just wouldn’t answer,” Williams says. Many of us have had this experience.

The school district finally dropped its mask mandate in March of 2022, after the decision from the state Supreme Court. And that was the end — except for one thing. A formal policy of the Unionville-Chadds Ford School District, Policy 906, establishes “a fair and impartial method” for the examination of parent complaints. You can find that policy here, in the section labeled “Community”. The policy is detailed and unambiguous, and starts requiring written reports after the failure of early and informal stages of resolution:

Third Level – If a satisfactory solution is not achieved by discussion with the building principal or immediate supervisor, a conference shall be scheduled with the Superintendent or designee. The principal or supervisor shall provide to the Superintendent or designee a report that includes the specific nature of the complaint, brief statement of relevant facts, how the complainant has been affected adversely, the action requested, and the reasons why such action should be taken or not taken.

Fourth Level – Should the matter not be resolved by the Superintendent or designee or is beyond his/her authority and requires Board action, the Superintendent or designee shall provide the Board with a complete report.

Final Level – After reviewing all information relative to the complaint, the Board shall provide the complainant with its written decision and may grant a hearing before the Board or a committee of the Board.

Williams used Policy 906 to ask the school board to think about what it had done, conducting an independent review of its policy decisions during the pandemic. Why had school officials implemented policies they had no legal authority to impose? Why had they refused to discuss or address parent questions? Why had they stonewalled requests for documents and information — not only from parents, but from a state senator who took an interest in the matter? Williams asked for an apology and “changes in oversight” to prevent a recurrence of unlawful and unexplained policy decisions, using formal school district policy that requires the district to act on complaints.

They haven’t bothered. The Unionville-Chadds Ford School District continues to ignore Williams, not responding to his complaints or opening the inquiry their own policy requires them to pursue. He’s had one sort-of response: In an exchange over the handling of the complaint, the district’s lawyers, at a private law firm, threatened him with legal action — a threat they so far haven’t made good. But from school district officials, the only response to three years of questions is unbroken silence.

January 26, 2021

The brief and inglorious life of Penn Central

In City Journal, Nicole Gelinas recounts the tale of the fateful merger of two great American railroad systems that lasted just long enough to support massive financial chicanery before descending into inevitable bankruptcy:

More than 50 years on now, the spectacular collapse of the Penn Central railroad in 1970 is little remembered today, but its legacy is still with us — not so much as a warning, but as a prelude: to New York City’s own near-bankruptcy in the 1970s; to four decades of financial engineering, beginning in the 1980s; to the 2001 Enron downfall; to the 2008 financial crisis and its “too big to fail” bailouts — and yes, even to the public discontent that elected President Donald Trump.

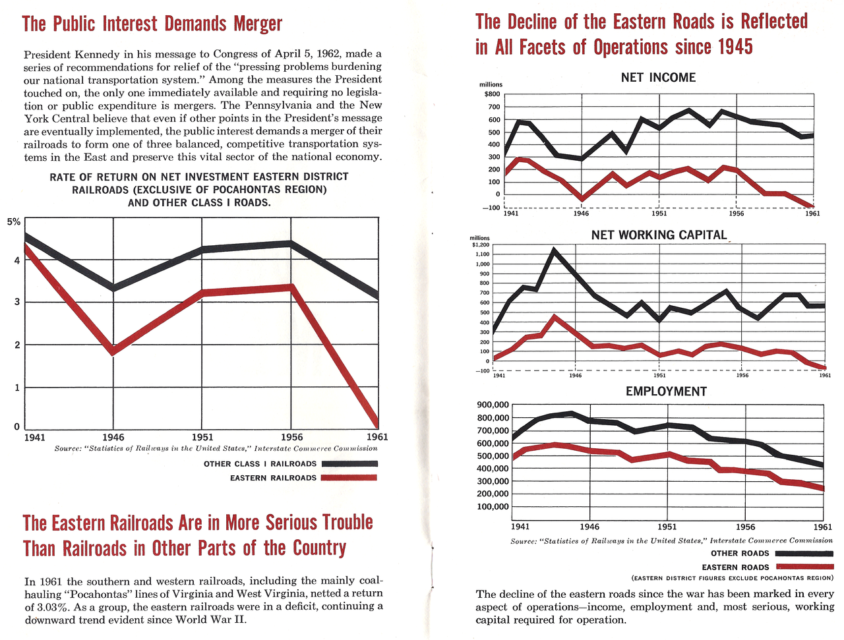

As America emerged from World War II, most people would have laughed at the idea of the nation’s two premier freight and passenger railroads, the Pennsylvania and the New York Central, going broke in a quarter-century’s time. By design, the Pennsy and the Central were not fierce competitors but complementary “frenemies” that had long agreed not to undercut one another’s monopoly profits. From Massachusetts to Missouri, the two railroads dominated freight and passenger travel in the northeast quarter of the United States, with nearly 21,000 miles of track between them.

Yet even as America built its powerhouse postwar economy, the railroads struggled. As Joseph R. Daughen and Peter Binzen write in The Wreck of the Penn Central, their cult-classic chronicle of the Penn Central’s demise, during the war the then-separate railroads had been running their equipment 24 hours a day to transport troops and supplies, leaving them with “worn-out” equipment.

In the fifties and sixties, moreover, new competitive pressures prevented them from catching their breath. Trucks competed with the railroads for freight hauling via the new, free highways the nation was building. Commuter-rail passengers moved to the highways as well, while long-haul rail passengers took to the skies. The railroads’ decline accelerated in the sixties, partly because of the collapse of northeast manufacturing.

In 1962, the two companies decided to merge. But railroading was one of the most heavily regulated industries in the United States, so the merger took six years, as it wound its way through multiple levels of public approval for the creation of the 100,000-worker, 100,000-shareholder, 100,000-creditor behemoth. Meantime, government-set rates already fell short of the railroads’ long-term costs.

The combined entity that would become the Penn Central made significant concessions to win political support for the merger, including no-layoff pledges that would hamper its ability to cut spending and a promise to take on the independent (and chronically insolvent) New York, New Haven, and Hartford passenger railroad.

After the merger, the railroads discovered that they had incompatible computer systems, which threw railyards into chaos and angered customers. The Penn Central’s three top officials, too, were incompatible. They “scarcely spoke to one another,” write Daughen and Binzen. Stuart Saunders, the board chairman, was a political guy. Alfred Perlman, the president, was a trains guy. These different outlooks could have complemented each other, but personalities got in the way. Rounding out this dysfunctional triumvirate was Penn vet David Bevan, the top financial official, perpetually “angry and humiliated” at not being picked for the top job.

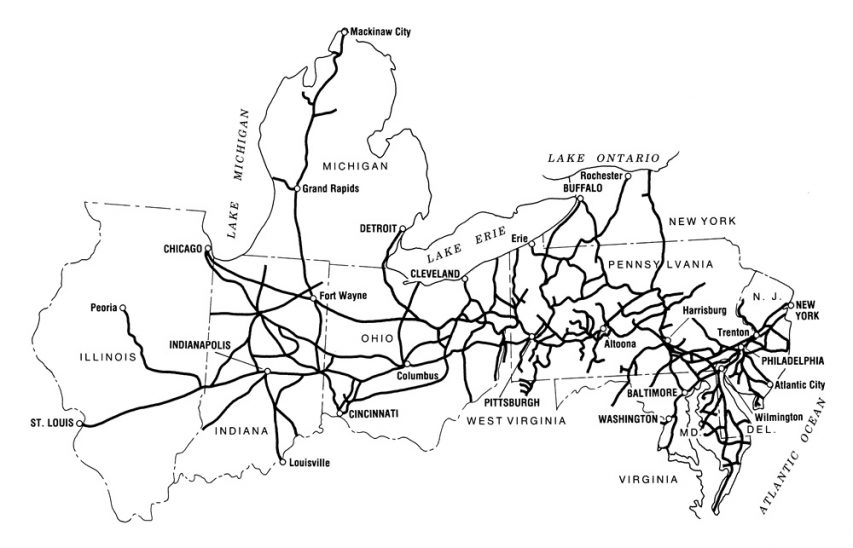

Penn Central route map from us.leforum.eu

http://us.leforum.eu/t1355-Photos-du-Penn-Central-PC.htm

H/T to Ed Driscoll at Instapundit, who also posted this video the combined entity put together to celebrate the merger:

January 21, 2021

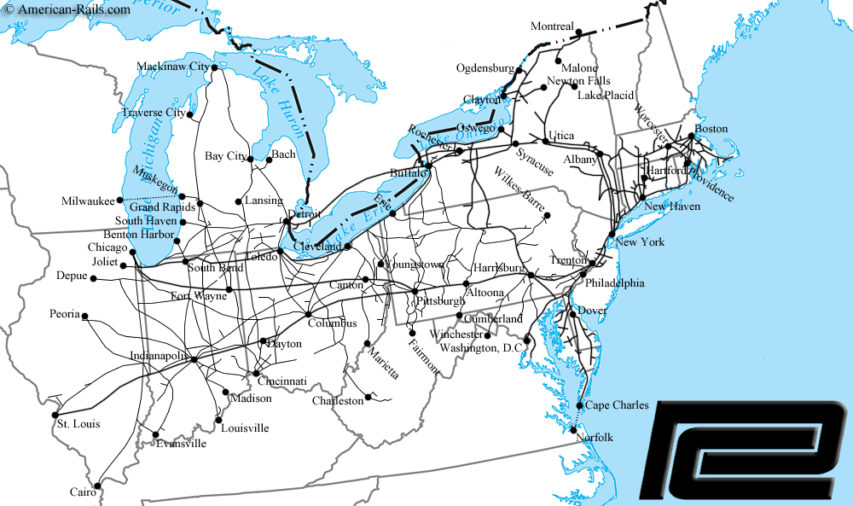

Fallen Flag — the New York Central System (part 2)

The New York Central System was the largest of the eastern trunk systems from the standpoint of mileage and second only to the Pennsylvania in revenue. It served most of the industrial part of the country, and its freight tonnage was exceeded only by the coal-carrying railroads. In addition it was a major passenger railroad, with perhaps two-thirds the number of passengers as the Pennsylvania, but NYC’s average passenger traveled one-third again as far as Pennsy’s. NYC did not share as fully in the post-World War II prosperity because of rising labor costs, material costs, and an expensive improvement program, especially for passenger service.

During 1946–47 Chesapeake & Ohio purchased a block of NYC stock, becoming the road’s largest stockholder. Robert R. Young gained control of the Central and became its chairman in 1954 as part of a maneuver to merge it with C&O. One of his first acts was to put Alfred E. Perlman in charge of the NYC.

Under Perlman NYC slimmed its physical plant, reducing long stretches of four-track line to two tracks under centralized traffic control, and developed an aggressive freight marketing department. At the same time NYC’s passenger operations were de-emphasized. On December 3, 1967, just before NYC and Pennsy merged, the Central reduced its passenger service to a skeleton, combining its New York–Chicago, New York–Detroit, New York–Toronto, and Boston–Chicago services into a single train and dropping all train names (including that of the legendary 20th Century Limited) except for, curiously, that of the Chicago–Cincinnati James Whitcomb Riley.

The Central’s archrival was the Pennsylvania Railroad. West of Buffalo and Pittsburgh the two systems duplicated each other at almost every major point; east of those cities the two hardly touched. Both had physical plant not being used to capacity (NYC was in better shape); both had a heavy passenger business; neither was earning much money. In 1957 NYC and Pennsy announced merger talks.

The initial industry reaction was utter surprise. Every merger proposal for decades had tried to balance the Central against the Pennsy and create two, three, or four more-or-less-equal systems in the east. Traditionally PRR had been allied with Norfolk & Western and Wabash; NYC with Baltimore & Ohio, Reading, and maybe the Lackawanna; and everyone else swept up with Erie and Nickel Plate. Tradition also favored end-to-end mergers rather than those of parallel roads.

Planning and justifying the merger took nearly ten years, during which time the eastern railroad scene changed radically, in large measure because of the impending merger of NYC and PRR: Erie merged with Lackawanna, C&O acquired control of B&O, and N&W took in Virginian, Wabash, Nickel Plate, Pittsburgh & West Virginia, and Akron, Canton & Youngstown.

Tradition aside, though, the New York Central and the Pennsylvania merged on Feb. 1, 1968 to form Penn Central.

November 17, 2020

Cancel culture comes for Donald Trump’s lawyers

Mark Steyn reported yesterday that the Lincoln Project’s latest doxxing has been successful and that a law firm representing President Trump in one of his Pennsylvania suits has been intimidated into withdrawing from the case:

Donald Trump addresses a rally in Nashville, TN in March 2017.

Photo released by the Office of the President of the United States via Wikimedia Commons.

Back in the summer I mentioned on The Mark Steyn Show that “cancel culture” was increasingly literal: It used to mean you got kicked off Twitter or Facebook; then it progressed to losing your job or television show or book contract. By 2020 it had advanced to being denied domain registration on the Internet, credit-card services, bank accounts and other basic necessities of modern life. Now, in a country with more lawyers than the rest of the planet combined, the supposedly “most powerful man on earth” wakes up and finds his counsel just canceled:

Lawyers with Porter Wright Morris & Arthur LLP submitted a filing late Thursday stating they were withdrawing as counsel in a federal suit seeking to block Pennsylvania from certifying its vote. No reason was given. In a statement issued Friday, the firm confirmed the filing but did not say why it was exiting the case.

Powerline‘s John Hinderaker reckons the reason is pretty obvious:

Porter Wright is a mid-sized law firm with offices in eight cities across the country. But apparently it lacked the courage to stand up against the Twitter mob. The “Lincoln Project” doxxed the two Porter Wright lawyers who signed the Pennsylvania complaint, tweeting their pictures, addresses and telephone numbers, and encouraging leftists to harass them. Reportedly there also were employees at the law firm who objected to representing President Trump. Porter Wright’s abandonment of its client is shameful conduct for which I suspect it will receive little but praise.

[UPDATE: A Powerline reader with knowledge of the situation says that Porter Wright has withdrawn from only one of five suits.]

As John points out, in America everybody from 9/11 plotters to celebrity pedophiles, Boston bombers to Oscar-winning serial rapists gets hotshot law firms and nobody bats an eyelid. But not Donald J Trump, who is apparently unfit for legal representation.

If you like the sound of all that “unity” and “healing”, this is what it boils down to — unity in the sense the Soviets meant it: the absence of opposition. And, when they’re done with Trump, they’re serious about that “Truth & Reconciliation” enemies list. To reiterate a point I’ve made for months: on free speech and related issues, things are going to head south very fast. I carelessly assumed they’d wait till the inauguration, but it seems “the Office of the President-Elect” is already on the case.

November 5, 2020

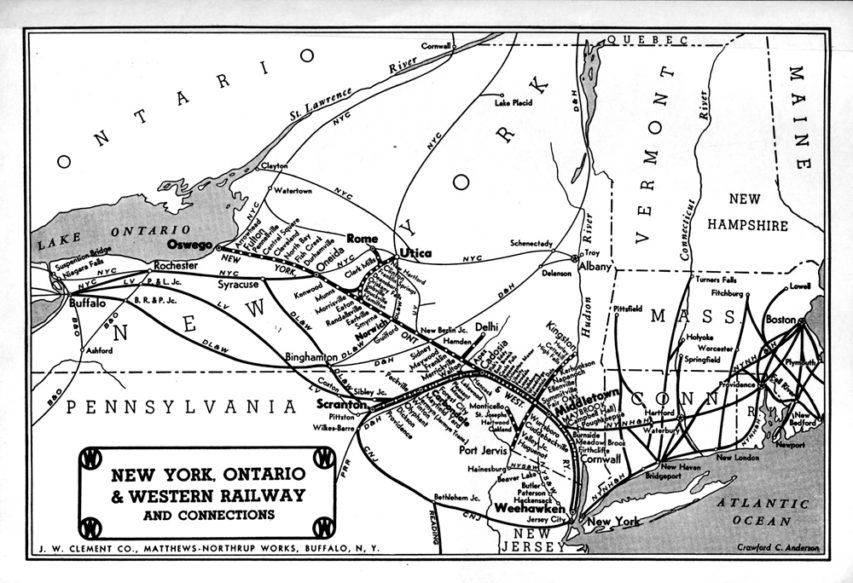

Fallen Flag — the New York, Ontario and Western Railway

This month’s Classic Trains featured fallen flag is the New York, Ontario and Western, which ran from Oswego on the south shore of Lake Ontario down into the New York City megalopolis. Sadly, the line is best remembered as the only Class 1 US railway to be completely abandoned. John R. Taibi outlines the history of the NYO&W from formation to abandonment in 1957:

This month’s Classic Trains featured fallen flag is the New York, Ontario and Western, which ran from Oswego on the south shore of Lake Ontario down into the New York City megalopolis. Sadly, the line is best remembered as the only Class 1 US railway to be completely abandoned. John R. Taibi outlines the history of the NYO&W from formation to abandonment in 1957:

Preserved NYO&W General Electric 44-ton switcher number 104 preserved at the Southeastern Railway Museum in Duluth, GA.

Photo by Harvey Henkelmann via Wikimedia Commons.

The New York, Ontario & Western Railway struggled to find its place among the many transportation systems serving New York City, but in the end it was able only to secure a place in history as the first Class I railroad to be abandoned in entirety. Despite this unenviable status, “the O&W,” as it was known, did endear itself to the communities along its line. After all, it was the carrier that had brought boxcars full of prosperity to every community along the line during its 76-year life.

Begun on January 21, 1880, the O&W set a goal of improving the Oswego–New York corridor, as well as the branches to New Berlin, Delhi, and Ellenville, N.Y., it had inherited from the New York & Oswego Midland. The O&W developed a new entrance to Gotham from Middletown, N.Y., that ran to Cornwall on the Hudson River, thence to Weehawken, N.J., by rights on the New York, West Shore & Buffalo Railway (later New York Central).

[…]

As it improved its physical characteristics, the O&W also acquired modern motive power to haul its numerous coal, milk, passenger, and general freight trains. Where previously Camelback 4-4-0s, 2-6-0s, and 2-8-0s were as common as the road’s wooden coaches and country depots, a corps of end-cab locomotives helped usher in the new era. E-class Ten-Wheelers (1911), W-class Consolidations (1910-11), X-class 2-10-2 “Bull Mooses” (1915), and Y-class Mountains (1922 and ’29) provided the power for passenger trains to the Catskills, milk trains to Gotham, and coal trains to Oswego, Cornwall, and Weehawken. Still, many Camelbacks worked into the mid-1940s.

This familiar, widely circulated O&W map was created by cartographer Crawford C. Anderson.

Classic Trains.[…]

Dieselization was hoped to be a savior, and under [O&W bankruptcy trustee, Frederick E.] Lyford’s direction a handful of GE 44-ton switchers arrived in 1941. Nine two-unit EMD FTs came in 1945 and were put into fast merchandise service between Scranton and Maybrook, and Scranton and Norwich. Lyford’s successors in 1948 acquired additional F3 and NW2 diesels, enough to banish steam locomotives from service by that summer.

By that time, though, O&W’s accumulated losses amounted to $38 million. It was beyond the ability of trustees, the reorganization court, and diesel locomotives to extricate the carrier from financial ruin. Nevertheless, passenger trains from Weehawken to Walton (then only to Roscoe) kept running until mail contracts gave out in 1950; the service was suspended in September 1953. Although milk and coal trains were a memory, gray-yellow-and-orange diesel locomotives soldiered on, leading a dwindling number of ever-shorter freight trains.

By the mid-1950s, the reorganization court — which had been searching for a buyer for the road now truly earning another of its nicknames, the “Old & Weary” — was advocating total abandonment. Additionally, the U.S. government was suing for taxes and retirement payments that were in arrears, and New York state began planning on how best to use the O&W right of way for highway improvements.

August 6, 2020

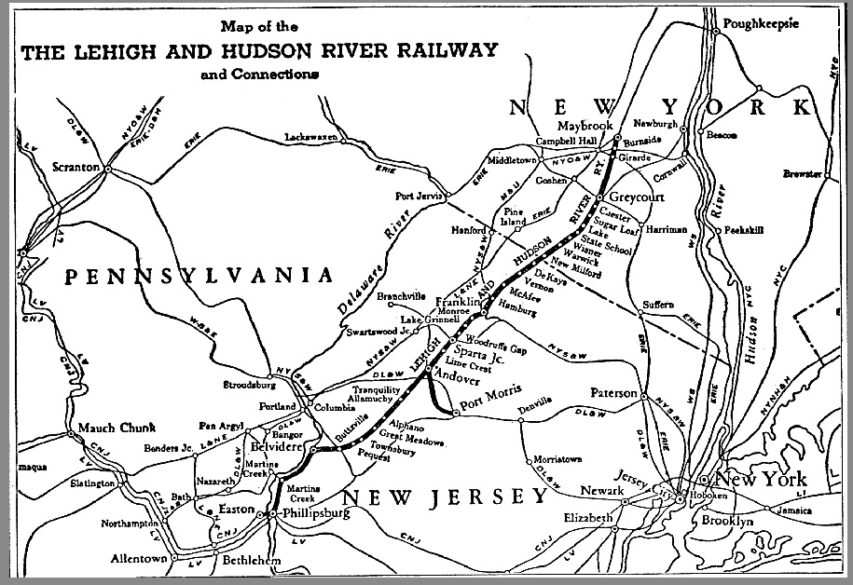

Fallen flag — The Lehigh and Hudson River Railway

This month’s Classic Trains featured fallen flag is a northeastern railway I didn’t know much about, the Lehigh and Hudson River. If you asked me to complete the phrase “Lehigh and …”, I’d most likely have said “New England”, which was a larger operation but is perhaps only remembered now as the second major American railway to file for abandonment after the New York, Ontario & Western. The L&HR earned its keep primarily as a bridge line, with additional revenues from online anthracite coal mines. From the original founding in 1881, it operated until it was incorporated into Conrail in 1976.

This month’s Classic Trains featured fallen flag is a northeastern railway I didn’t know much about, the Lehigh and Hudson River. If you asked me to complete the phrase “Lehigh and …”, I’d most likely have said “New England”, which was a larger operation but is perhaps only remembered now as the second major American railway to file for abandonment after the New York, Ontario & Western. The L&HR earned its keep primarily as a bridge line, with additional revenues from online anthracite coal mines. From the original founding in 1881, it operated until it was incorporated into Conrail in 1976.

L&HR’s origins date to 1860, when arrival of the New York & Erie Railroad, at Greycourt, New York, 10 miles north of Warwick, prompted construction of the Warwick Valley Railroad under the leadership of Grinnell Burt. The Warwick Valley operated as a 6-foot-gauge feeder to the same-gauge NY&E, using the big road’s equipment for two decades. Around 1880, WV assumed its own operations, was standard-gauged, and built the 11-mile Wawayanda Railroad, which tapped agricultural and mineral sources at McAfee, New Jersey. Further extension southward soon followed.

Two projected competitive lines were combined as the Lehigh & Hudson River Railroad, extending from a Pennsylvania Railroad connection at Belvidere, New Jersey, on the Delaware River, to Hamburg, New Jersey, where three miles of isolated Sussex Railroad track linked it to the Warwick Valley. In 1882 the extensions were folded into the 61-mile Lehigh & Hudson River Railway.

In addition to the New York & Erie’s mainline business at Greycourt, its Newburgh Branch provided access to Hudson River carferries crossing to the New York & New England’s Fishkill Landing. Anthracite coal, particularly from mines of affiliate Lehigh Coal & Navigation, was a major eastbound commodity. Anticipating completion of the Poughkeepsie Bridge a few miles upstream, the Orange County Railroad built north of Greycourt to connect with the New York, Ontario & Western at Burnside in 1890. Via trackage rights, this provided a first connection with the Central New England & Western at Campbell Hall, New York. Within a year, the Orange County was extended from Burnside to CNE’s new Maybrook yard.

Simultaneously, trackage rights were obtained from the Pennsy over 13 miles of its Belvidere-Delaware Division (“Bel-Del”) to Phillipsburg, New Jersey. There, disconnected subsidiaries undertook bridging the Delaware to access Easton, Pennsylvania, and the Jersey Central and Lehigh Valley. The bridge also opened in 1890, creating a three-state route of about 85 miles. The L&HR thus fulfilled the prescient vision of the line’s 1861 directors, who reported, “It was well understood by those … promoting the construction of the Warwick Valley Railroad, that in all probability it would be but a link in a great chain destined to be one of the most important thoroughfares, and to effect an important influence upon the commerce and manufacturers of an extensive section of our country …” Additional links soon extended the chain of this “important thoroughfare.”

January 3, 2020

Fallen flag – the Pennsylvania Railroad

The origins and an outline history of the “Standard Railroad of the World” for Classic Trains magazine by George Drury:

The original Pennsylvania Railroad ran from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh. Much of its subsequent expansion was accomplished by leasing or purchasing other railroads.

Construction began in 1847. Two years later the Pennsy made an operating contract with the Harrisburg, Portsmouth, Mountjoy & Lancaster, and by late 1852 rails ran from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh via a connection with the Portage Railroad between Hollidaysburg and Johnstown, Pa. The summit tunnel was opened in 1854, bypassing the inclined planes and creating a continuous railroad from Harrisburg to Pittsburgh.

In 1857 PRR bought the Main Line of Public Works and in 1861 leased the Harrisburg, Portsmouth, Mountjoy & Lancaster, putting the entire Philadelphia to Pittsburgh line under one management.

PRR also acquired interests in two major railroads, the Cumberland Valley and the Northern Central. The Cumberland Valley was opened in 1837 from Harrisburg to Chambersburg, and it was extended by another company in 1841 to Hagerstown, Maryland. The Baltimore & Susquehanna was incorporated in 1828 to build north from Baltimore. Progress was slowed because of the reluctance of Pennsylvania state officials to charter a railroad that would carry commerce to Baltimore. The line reached Harrisburg in 1851 and Sunbury in 1858. By then the railroad companies that formed the route had been consolidated as the Northern Central Railway. Pennsy acquired majority ownership of the Northern Central in 1900.

The Pennsy expanded into northwestern Pennsylvania by acquiring an interest in the Philadelphia & Erie Railroad in 1862 and assisting that road to complete its line from Sunbury to the city of Erie in 1864. The line to Erie was not particularly successful, but from Sunbury to Driftwood it could serve as part of a freight route with easy grades. The rest of that route was the Allegheny Valley Railroad, conceived as a feeder from Pittsburgh to the New York Central and Erie railroads. The Pennsylvania obtained control in 1868, and in 1874 opened a route with easy grades from Harrisburg to Pittsburgh via the valleys of the Susquehanna and Allegheny rivers. PRR leased the Allegheny Valley Railroad in 1900.

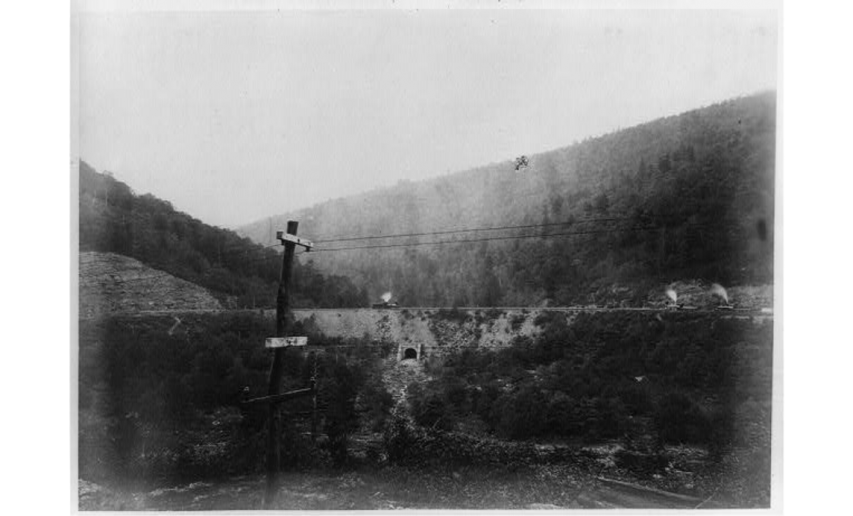

Horse shoe curve near Altoona on the Pennsylvania Railroad, circa 1874.

Photo by W.P. Mange & Co. via the Library of Congress.

But even the mighty can fall, and the PRR fell into difficult times after WW2:

During World War II Pennsy’s freight traffic doubled and passenger traffic quadrupled, much of it on the eastern portion of the system. The electrification was of inestimable value in keeping the traffic moving. After the war Pennsy had the same experiences as many other railroads but seemed slower to react. PRR was slower to dieselize, and when it did so it bought units from every manufacturer.

As freight and passenger traffic moved to the highways, Pennsy found itself with far more fixed plant than the traffic warranted or could support, and it was slow to take up excess trackage or replace double track with Centralized Traffic Control.

PRR was saddled with a heavy passenger business. It had extensive commuter services centered on New York, Philadelphia, and Pittsburgh and lesser ones at Chicago, Washington, Baltimore, and Camden, New Jersey. It had gone through the Depression without going bankrupt.

Pennsylvania and New York Central surprised the railroad industry by announcing merger plans in 1957. The two had long been rivals, and the merger would be one of parallel roads rather than end-to-end. The merger took place on February 1, 1968 — and Penn Central fell apart faster than it went together.

December 19, 2018

Krampus – Christmas Demon – Extra Mythology

Extra Credits

Published on 17 Dec 2018Join the Patreon community! http://bit.ly/EMPatreon

Krampus’s name is growing popular in the United States, but most of us don’t really know what he does OR that he is partners with St. Nicholas himself. He is in fact just one of many Christmas demons…

July 7, 2018

History Buffs: Gettysburg

History Buffs

Published on 19 Feb 2018

January 7, 2018

QotD: The Whiskey Rebellion

Ninescore and fifteen years ago, with the ink only just sanded on the United States Constitution, President George Washington and Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton decided it was time to try out their shiny brand-new powers of taxation.

Their first victims would be certain western Pennsylvania agricultural types long accustomed to converting their crops into a less perishable, more profitable high-octane liquid form. Unfortunately for the President and the Secretary, many of these rustics, especially near the frontier municipality of Pittsburgh, placed a slightly different emphasis than high school teachers do today on the Revolutionary slogan regarding “taxation without representation”. In their view, they’d fought the British in 1776 to abolish taxes and they weren’t interested in having representation imposed on them by that gaggle of fops in Philadelphia, the nation’s capital. They made this manifestly clear by tarring-and-feathering tax collectors, burning their homes to the ground, and filling the stills of those who willingly paid the hated tribute with large-caliber bullet holes.

Feeling their authority challenged, George and Alex dispatched westward a body of armed conscripts equal to half the population of America’s largest city (Philadelphia once again, later famous for air-dropping explosives on miscreants charged with disturbing the peace). Four hundred whiskey rebels, duly impressed by this army of fifteen thousand, subsided. The miraculous process by which the private act of thievery is transubstantiated into public virtue was firmly established in history. The results — chronic poverty and unemployment, endless foreign wars, and reruns on television — are with us even today.

L. Neil Smith, “Introduction: A Brief History of the North American Confederacy”, The Spirit of Exmas Sideways: a “novelito” by L. Neil Smith.

May 6, 2016

QotD: The Quakers

Fischer warns against the temptation to think of the Quakers as normal modern people, but he has to warn us precisely because it’s so tempting. Where the Puritans seem like a dystopian caricature of virtue and the Cavaliers like a dystopian caricature of vice, the Quakers just seem ordinary. Yes, they’re kind of a religious cult, but they’re the kind of religious cult any of us might found if we were thrown back to the seventeenth century.

Instead they were founded by a weaver’s son named George Fox. He believed people were basically good and had an Inner Light that connected them directly to God without a need for priesthood, ritual, Bible study, or self-denial; mostly people just needed to listen to their consciences and be nice. Since everyone was equal before God, there was no point in holding up distinctions between lords and commoners: Quakers would just address everybody as “Friend”. And since the Quakers were among the most persecuted sects at the time, they developed an insistence on tolerance and freedom of religion which (unlike the Puritans) they stuck to even when shifting fortunes put them on top. They believed in pacificism, equality of the sexes, racial harmony, and a bunch of other things which seem pretty hippy-ish even today let alone in 1650.

England’s top Quaker in the late 1600s was William Penn. Penn is universally known to Americans as “that guy Pennsylvania is named after” but actually was a larger-than-life 17th century superman. Born to the nobility, Penn distinguished himself early on as a military officer; he was known for beating legendary duelists in single combat and then sparing their lives with sermons about how murder was wrong. He gradually started having mystical visions, quit the military, and converted to Quakerism. Like many Quakers he was arrested for blasphemy; unlike many Quakers, they couldn’t make the conviction stick; in his trial he “conducted his defense so brilliantly that the jurors refused to convict him even when threatened with prison themselves, [and] the case became a landmark in the history of trial by jury.” When the state finally found a pretext on which to throw him in prison, he spent his incarceration composing “one of the noblest defenses of religious liberty ever written”, conducting a successful mail-based courtship with England’s most eligible noblewoman, and somehow gaining the personal friendship and admiration of King Charles II. Upon his release the King liked him so much that he gave him a large chunk of the Eastern United States on a flimsy pretext of repaying a family debt. Penn didn’t want to name his new territory Pennsylvania – he recommended just “Sylvania” – but everybody else overruled him and Pennyslvania it was. The grant wasn’t quite the same as the modern state, but a chunk of land around the Delaware River Valley – what today we would call eastern Pennsylvania, northern Delaware, southern New Jersey, and bits of Maryland – centered on the obviously-named-by-Quakers city of Philadelphia.

Penn decided his new territory would be a Quaker refuge – his exact wording was “a colony of Heaven [for] the children of the Light”. He mandated universal religious toleration, a total ban on military activity, and a government based on checks and balances that would “leave myself and successors no power of doing mischief, that the will of one man may not hinder the good of a whole country”.

His recruits – about 20,000 people in total – were Quakers from the north of England, many of them minor merchants and traders. They disproportionately included the Britons of Norse descent common in that region, who formed a separate stratum and had never really gotten along with the rest of the British population. They were joined by several German sects close enough to Quakers that they felt at home there; these became the ancestors of (among other groups) the Pennsylvania Dutch, Amish, and Mennonites.

Scott Alexander, “Book Review: Albion’s Seed“, Slate Star Codex, 2016-04-27.

November 30, 2015

The Pennsylvania Steagles

Megan McArdle talks about the plight of Pennsylvania’s two NFL teams during World War Two … oh, and some boring stuff about financial regulation:

Fun fact: During the 1943 professional football season, the World War II draft had so depleted the ranks of football players that the Pittsburgh Steelers and the Philadelphia Eagles were forced to unite their teams into a joint production that became colloquially known as “the Steagles.” In a heartwarming turn, this plucky band of men went on to one of the winningest seasons in the history of Pennsylvania football. That was, alas, their only season; the next year each city fielded its own team, and the proud name of the Steagles retreated into history.

I’m beginning to think that we should revive it, however, not for football players, but for those intrepid souls who continue to fiercely agitate for the return of the Glass-Steagall financial regulations. Like the Steagles, these people are not daunted by the many obstacles in their path. Like the Steagles, they are passionate in their determination. Probably also like the Steagles, they mostly don’t know much about Glass-Steagall.

And we desperately need a name for Team Steagles, because they seem to have become a powerful force in the Democratic Party. Last night’s Democratic debate, like the first one, featured lengthy paeans to the joys, and urgency, of a modern Glass-Steagall act. Somehow, an obscure Depression-era banking regulation has turned into a banal political talking point. Or worse — a distraction.

You, like the Steagles, may not know much about Glass-Steagall. That’s all right. There is no particular reason that most of us should know about Glass-Steagall, and many people manage to live perfectly happy and fulfilling lives anyway.