Forgotten Weapons

Published on 6 Mar 2019http://www.patreon.com/ForgottenWeapons

Cool Forgotten Weapons merch! http://shop.bbtv.com/collections/forg…

The Springfield Arms Company existed only for a brief period in 1850 and 1851, making revolvers designed by its chief engineer, James Warner, before being driven out of business by Colt patent lawyers. During that time, Springfield (no relation to the arsenal) made a variety of models in .28, .31, and .36 caliber and with a variety of barrel lengths and other features (including a well-designed safety notch to allow the guns to be carried fully loaded safely). In an attempt to avoid patent infringement, Warner separated the cylinder rotation and firing mechanisms into two different triggers on some models, including this Navy pattern example. The front trigger would rotate and lock the cylinder, and then it would trip the rear trigger which released the sear and fired the gun. This was not sufficient to save him from copyright infringement suits, though, and only about 125 of the double-trigger Navy revolvers were made.

Contact:

Forgotten Weapons

PO Box 87647

Tucson, AZ 85754

April 6, 2019

Springfield Arms Double Trigger Navy Revolver

March 11, 2019

How Does It Work: Patents and Blueprints

Forgotten Weapons

Published on 10 Feb 2019http://www.patreon.com/ForgottenWeapons

Cool Forgotten Weapons merch! http://shop.bbtv.com/collections/forg…

What is the difference between patents and copyrights? If someone wants to reproduce an old firearm design, how do they get the rights to? Why can’t you reproduce a gun design from patent drawings? What information is in a technical data package? This and more, today on How Does It Work!

Contact:

Forgotten Weapons

PO Box 87647

Tucson, AZ 85754

October 27, 2018

The Progressive case for Americans to pay higher drug prices than the rest of the world

Tim Worstall carefully explains — in full compliance with Progressive philosophy and pointing out that Trump is wrong (which is extra bonus Progressive points) — why Americans should continue to pay more for drugs that are cheaper in other countries:

Working out which drugs work and how is expensive. There’s then another expensive in actually proving this well enough to gain a licence. All in costs are in the $1 to $2 billion range dependent upon who you want to listen to. Unfortunately, once you’ve done all that and paid all that anyone could just come along and copy your drug. Which means you don’t make your $2 billion back – that in turn meaning that no one does spend $2 billion, we don’t get new drugs and we all die in ditches.

This is a classic public goods problem and the solution we use – not the only one, not even the only viable one – is patents. You get about 10 years, the time between approval and patent expiry, to make your $2 billion back. Then anyone can copy it and we all get cheap copy drugs.

For this system to work it is not necessary that everyone pay these high patent protected prices. There’s no point in trying to charge some farm worker in S Africa $10,000 a year for HIV retrovirals anyway, they don’t have the cash and demanding it will gain nothing except their death. We just need some group to pay the high prices so that drug development still happens. Everyone else can get drugs at some margin above their manufacturing, not development, costs.

So, who is it who should be carrying this cost of producing this public good? Good progressive principles tell us that it should be the rich folk. Imagine that we used some other system of drug development, maybe taxpayers cough up for it all. It’ll still be the rich doing the paying, right? So, patents, where the rich pay full freight for drugs, the poor don’t, this meets our equity criterion.

And who are the rich in this global sense, for we’re talking about a global public good here? That would be the citizens of the richest large nation, the largest rich nation, the United States of America. So, yes, Americans should be paying high prices for drugs and the rest of us shouldn’t.

Do note that we’ve used impeccable redistributionist logic to reach this conclusion. It’s only if you think the rich shouldn’t be paying to benefit the poor that this is a bad idea. Which might be why Trump is agin it but it still puzzles as to why the progressives would be.

August 4, 2018

Rhodesia Made Their FALs Great With This One Weird Halbek Device!

Forgotten Weapons

Published on 14 Jul 2018http://www.patreon.com/ForgottenWeapons

The Halbek Device was a clamp-on muzzle brake designed by two Rhodesians, Douglas Hall and Marthinus Bekker. It was patented in Rhodesia in 1977 and in the US in 1980, and manufactured in small numbers for the Rhodesian military. I have seen these occasionally, and doubt they are actually very effective. But during a filming trip to South Africa I had a chance to actually try one on a select-fire R1 FAL, complete with high speed camera to find out for sure. So, let’s see what they really do…

If you enjoy Forgotten Weapons, check out its sister channel, InRangeTV! http://www.youtube.com/InRangeTVShow

February 26, 2018

A few jotted notes on woodworking plane companies

I’ve been dabbling more in the woodworking hand tool market recently, and found myself getting confused about the various manufacturers and their products. Mostly to try to sort out the history for myself, I started taking notes as I trawled from website to forum to auction site, looking for answers. In a very abbreviated and assuredly incomplete and inaccurate thumbnail sketch, here’s how I think the woodworking hand tool market has changed over the last hundred and fifty years or so:

- Until the mid-19th century, most woodworkers made their own tools whenever they could, as the ability of manufacturers to produce economical, dependable tools was limited, and woodworkers (like other skilled craftsman of the early industrial era) were capable of producing most of the necessary tools with only minimal outlay to other trades.

- By the mid-19th century, innovators and inventors were prolific in their proposed solutions to all kinds of problems (some real and many probably imaginary). Among those many, many febrile innovators was a gentleman named Leonard Bailey. Bailey managed to almost single-handedly revolutionize the woodworking market by coming up with a line of hand planes that could out-compete most of the hand-made competitors while taking advantage of the economies of scale offered by mass production. It became more economical for a woodworker to buy a ready-made tool rather than take time away from productive work to fabricate it for himself.

- The Stanley Works of Massachusetts bought Bailey’s company — probably more for the value of Leonard’s patents than for the company’s sake itself — and parlayed that patent protection into becoming the acknowledged standard for woodworking planes.

- Even after the Bailey patents expired, other manufacturers paid backhanded tribute to Bailey by straight-out cloning his designs with very minor changes and putting their own functional copies on sale in direct competition with the original Stanley products … often even using the same or barely concealed names/numbers for their clones (for example, the British company Record generally just prepended a zero in front of the “standard” Stanley model numbers, where a #4 plane from Stanley was a #04 from Record).

- In the British market following the financial crisis of 1929, the government’s imposition of tariffs against inter alia American hand tool manufacturers encouraged many British companies to introduce Stanley clones for both domestic and Imperial markets. To their credit, not all of the opportunistic entrants went for the low-hanging fruit, and some of the British clones were at least as good and in some cases superior to the original products.

- After the Second World War, the market for woodworking hand tools in North America began a rapid decline, although it remained strong enough in Britain to keep many of the clone manufacturers going for another 20 years or so. In response to the softening market, Stanley began to cheapen their manufacturing processes and the product quality began a precipitous decline.

- By the early 1970s, Stanley had almost completely given up the hand tool market in woodworking, and their products were a sad mockery of what they’d been producing just a decade before, but North American woodworkers were inundated with innovative power tools from, among others, Black & Decker and the Sears Craftsman line that promised better/faster/more productive output from amateur woodworking shops than could be done with hand tools alone. That, coupled with the decreased emphasis on “shop” subjects in North American high school curricula meant that youngsters didn’t automatically become familiar with the use of hand tools unless they were already interested and had access to a workshop to indulge that interest.

- The same process of shrinking market requiring “rationalization” and “economization” hit the British manufacturers fifteen to twenty years after Stanley and their surviving American competitors, and the order of the day was ever-shrinking profit margins, smaller markets, and mergers/bankruptcies/take-overs among the tool manufacturers.

- After the financial bloodbath of the 70s through the 90s, it became clear that there was still a small-but-affluent market for quality woodworking hand tools, and a few new entrants made their mark by first copying the best designs of the past and then, hesitatingly, innovating with modern technology beyond what was possible a generation or two earlier.

Here are some notes I jotted down about a few of the key woodworking hand tool manufacturers and their respective rise and decline, based on a very cursory survey of what information is available online at the moment:

STANLEY (USA, UK, CANADA and AUSTRALIA)

A vintage Stanley No. 4 smoothing plane from a recent eBay listing. Even though this is the single most common woodworking plane ever, the example I own is a late-70s piece of crap, so I went looking for a more representative image.

The Stanley Works was founded in 1843 by Frederick Stanley in New Britain, Connecticut.

In 1857, the Stanley Rule & Level Company was founded by Frederick Stanley’s cousin Henry. I imagine most people of the time assumed there was only the single Stanley company, as they produced products in related-but-not-competitive fields.

Stanley purchased Bailey, Chaney and Company in 1869 along with the Bailey plane patents. The Bailey patents were the key to Stanley’s future dominance of the hand plane market.

Stanley Rule & Level Co. purchased the Roxton Tool and Mill Company in Roxton Pond, Quebec (founded 1873). Manufacturing continued here from 1907 until about 1984. From the timing, I assume this was seen as a good way to get Stanley hand tools into the Canadian market without paying tariffs.

In 1920, The Stanley Works merged with the Stanley Rule & Level Company. The initials “S.W.” within a heart outline was introduced at that time. Later references to tools with this mark invariably refer to them as “Sweetheart”, but it’s not clear that the newly unified Stanley used that term in their own marketing until a few years later. The logo and name have been revived in the last decade or so, probably to cash in on the nostalgia factor.

In 1937, Stanley acquired J.A. Chapman (of Sheffield, England). I’m assuming this was a shortcut to getting non-tariff access to the British (and Imperial) hand tool market.

Stanley manufactured planes in Australia from 1965 to the early 1990s in Moonah, Tasmania.

In 2010, The Stanley Works merged with Black & Decker to become Stanley Black & Decker (Stanley Hand Tools is a division of the much larger company).

MILLERS FALLS (USA)

I happen to actually own a Millers Falls #9 smoothing plane (as of Friday). Look similar to the Stanley #4 above? It should, as it’s a near-clone.

Incorporated in 1868 as the Millers Falls Manufacturing Company, renamed as the Millers Falls Company in 1872. Introduced hand planes into its line of tools in 1928/29. Millers Falls chose to compete for the high-end of the hand tool market and managed to carve out a profitable niche for themselves, especially in the hand plane segment. Their futuristic plastic-and-chrome “Buck Rogers” planes of the late 1950s were visually distinctive enough that they kept the company in the black for longer than almost all of their US competitors.

In 1957, Millers Falls acquired the Union Tool Company of Orange, Massachusetts. The Union brand was kept active until 1975 when the Union plant was closed down.

Millers Falls became a subsidiary of Ingersoll Rand in 1962, and closed down their Massachusetts operation in 1982 with a corporate relocation to New Jersey after a buyout.

RECORD (UK)

(front) A Record No. 05 jack plane, a close copy of the Stanley #5

Record was a brand name used by C & J Hampton from 1909. The company was founded in 1898 and incorporated a decade later. The founders, Charles and Joseph Hampton, had left the family business (The Steel Nut & Joseph Hampton Ltd in Wednesbury, Staffordshire) to set up shop in Sheffield. Joseph eventually returned to the family firm, but the sons of Charles succeeded to leadership roles in the younger company.

The first Record planes were offered for sale in 1931 (No. 03 through 08 and three block planes: No. 0110, 0120 and 0220). Record got into the plane business partly due to the preferential tariffs the British government levied on foreign (mainly American) hand tools and the fact that the Stanley Works’ Bailey patents had expired, so there was no legal issue with flat-out cloning Stanley’s plane line.

In 1934, Record took over production of some Edward Preston and Sons Ltd. products (mainly bullnose and rabbet planes). Preston had been acquired by John Rabone and Sons Ltd. (Birmingham) in 1932, but they decided to stick with the rule and level business and offload the plane manufacturing to Record.

Woden Tools Ltd was purchased from The Steel Nut & Joseph Hampton Ltd in 1961 and Record continued to use the Woden trademark for another 10 years (some sources say only five years: take your pick).

Record acquired 50% of William Marples and Sons Limited in 1963, the other 50% being held by William Ridgway & Sons, Ltd. (Parkway Works), also of Sheffield.

In 1972, Record merged with Ridgway to form Record Ridgway Tools Ltd.

In 1982, Record Ridgeway was acquired by AB Bahco of Sweden, but a management buyout in 1985 took it back to British ownership as Record Holdings plc.

In 1988 the company became Record Marples (Woodworking Tools) Ltd.

In 1998, Record Marples accepted an offer from American Tool Corporation and became part of the Record Irwin Group as Record Tools Ltd. Irwin was acquired by Stanley Black & Decker in 2017.

WODEN TOOLS (UK)

Woden Tools was a wholly owned subsidiary of The Steel Nut & Joseph Hampton Ltd, producing planes from 1953/54 in Wednesbury, Staffordshire. (The planes were originally manufactured by W.S Manufacturing (Birmingham), which was acquired by The Steel Nut & Joseph Hampton around 1952.)

C & J. Hampton (Record) purchased Woden Tools Ltd from SNJH in 1961 and continued to use the Woden trademark for another 10 years (some sources say only until 1965).

LEE VALLEY/VERITAS (CANADA and USA)

Founded in 1978 by Leonard Lee in Ottawa, Ontario. The first out-of-town store was opened in 1982 (Toronto West). I think I visited that store in its original location in 1984. The company launched their website in 1997 and added e-commerce features in 2000.

In the early-to-mid 1980s, Lee Valley contracted with Footprint (UK) to produce a line of bench planes to their specifications. The “Paragon” line were sold in Canada by Lee Valley and by Garret Wade in the United States for a few years, but quality issues apparently doomed the venture. In a thread on the Sawmillcreek.org forums, Robin Lee said “Actually – we ‘remanufactured’ many of them here [in Ottawa]… We set out the specs, made some tooling changes, and had Footprint make them for us (and GW). All planes were received and inspected … – and in many cases, fettled and reground… We abandoned the brand shortly after – and formed Veritas tools as our manufacturing company…”

In 1999, the first Lee Valley manufactured plane, the Low-Angle Block Plane, was introduced. The Veritas line of bench planes was launched in 2001. The first shoulder plane was introduced in 2003. In 2014, the Veritas Custom Bench Plane line was introduced, which the company characterizes as the first user-customizable line of planes in the industry.

In 1982, the company began manufacturing its own tools under the Veritas label. In 1985, Lee Valley Manufacturing Ltd. was incorporated and later renamed as Veritas Tools, Inc. Manufacturing is primarily in Ottawa and (possibly) in Ogdensburg, New York.

November 17, 2017

Is There Any Cheese in Cheez Whiz? (And the Story of Kraft)

Today I Found Out

Published on 5 Nov 2017In this video:

As America gets ready for their upcoming Super Bowl parties (or Royal Rumble party, if that’s your thing), Cheez Whiz – the yellowish-orange, gooey, bland tasting “cheese” product – will surely make an appearance at some of them. But what is Cheez Whiz? Why did get it invented? And is there really cheese in Cheez Whiz?

Want the text version?: http://www.todayifoundout.com/index.php/2015/01/cheese-cheez-whiz/

October 8, 2017

Electricity – Wright Brothers – Hip Firing MGs I OUT OF THE TRENCHES

The Great War

Published on 7 Oct 2017Chair of Wisdom Time! This week we talk about the advancements of electricity during the war, the Wright brothers patent wars and hip/shoulder firing MGs. Oh and Italian Spiderman.

October 6, 2017

Are Branded Drugs Better? – Earth Lab

BBC Earth Lab

Published on 22 Jun 2017When you’ve got a cold and need some medicine, do you ever wonder if there’s a difference between branded and non-branded drugs? Greg Foot explains the world of pharmaceuticals, backed up with some stonking examples and unexpected findings!

September 17, 2017

But is it full of eels? If not, feel free to visit the British Hovercraft Museum

In their continuing series of “Geeks’ Guide to Britain”, The Register takes a trip to the former HMS Daedalus, a Fleet Air Arm seaplane training base that is now home to the Hovercraft Museum:

Did you know that the word “hovercraft” was once patented? And did you know that Great Britain is a world leader in the design and manufacture of the floaty transporters, and has been for half a century?

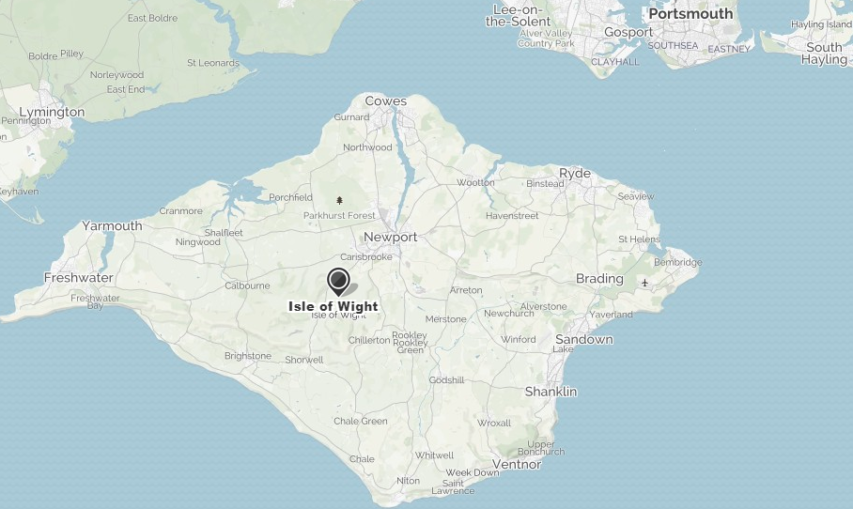

These and other surprising facts – including that some of the largest commercial hovercraft ever to be used in revenue service spent their lives shuttling booze cruisers back and forth across the English Channel – can be found at the Hovercraft Museum, at Lee-on-Solent in the south of England.

A century ago, what is now the site of the museum was known as HMS Daedalus and used as a Fleet Air Arm seaplane base. Back in the early days of aviation, and especially naval aviation, the station was at the forefront of naval and aviation technology alike. Seaplanes and skilled pilots were in great demand by the Royal Navy for anti-submarine patrols, and a new training base had to be set up to fill the service’s demand.

Thus came about the “temporary” Naval Seaplane Training School at Lee-on-Solent, with the new training school being based around a large local property, Westcliffe House. Slipways and hangars were duly erected, with the former leading down into the waters of the Solent itself; of the latter, one of the original J-class hangars, capable of being erected by just 15 men, survives to this day.

[…]

To truly appreciate the hovercraft, one should actually ride one of the things. This is easily done by a short journey along the coast from Lee-on-Solent to Britain’s only scheduled hovercraft service, which operates between Portsmouth and the Isle of Wight.

Operated by Hovertravel, whose sister company Griffon Hoverwork also builds the craft operated by the company, the service runs about every half an hour during the day, with more frequent services during the morning rush hour and a gradual winding-down into the evening.

August 12, 2017

Troll the Patent Trolls

Published on 11 Aug 2017

Patent trolls are on the run. Let’s finish them off.

———

It’s been a bad year for patent trolls, from a Supreme Court decision squelching their ability to funnel lawsuits to East Texas, to this week’s ruling that Personal Audio LLC can’t claim it owns a patent on the entirety of podcasting. In the latest Mostly Weekly, Reason’s Andrew Heaton explores what patent trolls are, the damage they do, and the next step in driving them out of courtrooms and back into dank caves.Trolls camp out on piles of weak and frivolous patents, hoping to one day sue inventors and businesses. Many of the patents they register or buy are vague, representing novel ideas only insofar as trolls are innovative at finding things they didn’t invent to claim legal ownership of. It doesn’t matter that these patents wouldn’t hold up in court, because a business is more likely to pay off a troll than to hire an expensive attorney to fight them. Trolls suck more than twenty billion dollars out of the economy each year.

The parasitical nature of “non-practicing entities” (the PC term for trolls) has raised questions about whether the modern patent system helps or hinders innovation, and if the best solution is for comprehensive reform or just to burn the whole thing down.

Heaton has an idea to hinder patent trolls. It may not be a silver bullet, but it will definitely piss them off.

Mostly Weekly is hosted by Andrew Heaton with headwriter Sarah Rose Siskind.

Script by Andrew Heaton with writing assistant from Sarah Siskind

Edited by Austin Bragg and Sarah Rose Siskind.

Produced by Meredith and Austin Bragg.

Theme Song: Frozen by Surfer Blood.

July 31, 2017

Patents, Prizes, and Subsidies

Published on 17 May 2016

Growth on the cutting edge is all about the creation of new ideas.

So, we want institutions that incentivize such creation. How do we do this? The answer is somewhat tricky.

The first goal for good ideas is for them to spread as freely as possible. The further the reach, the greater the gains. The problem is, if just anyone can use ideas, then why would we ever pay for them? And without the right incentives, why would innovators create new ideas at all?

Imagine yourself as the creator of a new drug. Typically, it costs about a billion dollars to do this, not counting the time and effort needed to get the drug FDA-approved.

Now, if there were no protections in place, then theoretically, once the formula’s known, everyone could just copy the make-up of your new drug. See, the thing about pharmaceuticals is, once the formula’s known, production is relatively cheap. Given that, let’s assume imitations start flooding the market.

Predictably, the price of your new drug will plummet.

Once prices hit rock-bottom, you’ll have no way to recoup the $1 billion you spent on R&D.

Given that kind of result, we reckon you probably won’t want to develop more good ideas.

The US founding fathers anticipated this problem. Knowing that innovators needed incentives to have good ideas, the founders wrote a protection mechanism into the Constitution.

They gave Congress the ability to grant exclusive rights to inventors — rights to use and sell their inventions, for a limited period of time. This exclusive right, is what we call a patent. Patents grant inventors a temporary monopoly over the use and sale of their intellectual property.

Now, as nice as this is, patents are a thorny subject.

For one, how long should patents last? Also, how much innovation is considered enough to merit a patent grant? Not to mention, are patents the only way to reward good ideas?

The answer is no.

There are two more incentive options here: prizes, and subsidies.

Let’s start with subsidies. University and research subsidies are particularly effective in the basic sciences. Since innovations in this space are rather abstract, subsidies incentivize research without requiring the applications of the research to be explicitly named. The problem is, when we’re incentivizing just research, then researchers might pick directions that are interesting, but not particularly useful.

This is why the third incentive option — prizes — exists.

Prizes reward the output of solving a certain problem. Another plus, is that prizes leave solutions unspecified. They provide a problem to work on, but give quite a lot of leeway as to how the problem is solved.

Now, knowing the complexity inherent in patents, you might think that prizes and subsidies are good enough alternatives. But none of these incentives for ideas, are inherently better than any of the others. Patents, prizes, and subsidies all involve their own tradeoffs and questions.

For example, who decides what gets subsidized? Who decides which goals merit a prize?

It’s hard to determine what mix of institutions, will best incentivize the production of good ideas. Patents, prizes, and subsidies all navigate these conflicting goals, in their own way.

And yes, all this talk of incentives and conflicting goals and tradeoffs might be like walking a tightrope. But, it’s a tightrope we can’t opt out of. Certainly not if we want the economy to keep growing.

In our next release, you’ll watch a TED talk from a certain economist that elaborates further on ideas. And then, we’ll wrap up this course segment with the Idea Equation. Stay tuned!

December 2, 2015

Maximizing Profit under Monopoly

Published on 18 Mar 2015

AIDS has killed more than 36 million people worldwide. There are drugs available to treat AIDS, but the price of one pill is incredibly high in the U.S. — coming in at 25 times higher than its cost. Why is that? In this video, we show how patent rights have created a monopoly in the U.S. market for AIDS medication, causing pills to be very expensive. In other countries, however, such as India, which does not recognize patents on AIDS medication, prices remain low. Using this example, we go over how monopolies use market power to increase prices.

October 12, 2015

Is the ballpoint pen the reason we all write so badly now?

In The Atlantic, Josh Giesbrecht postulates that our penmanship went south in parallel with the rise of the ballpoint pen:

Recently, Bic launched a campaign to “save handwriting.” Named “Fight for Your Write,” it includes a pledge to “encourage the act of handwriting” in the pledge-taker’s home and community, and emphasizes putting more of the company’s ballpoints into classrooms.

As a teacher, I couldn’t help but wonder how anyone could think there’s a shortage. I find ballpoint pens all over the place: on classroom floors, behind desks. Dozens of castaways collect in cups on every teacher’s desk. They’re so ubiquitous that the word “ballpoint” is rarely used; they’re just “pens.” But despite its popularity, the ballpoint pen is relatively new in the history of handwriting, and its influence on popular handwriting is more complicated than the Bic campaign would imply.

The creation story of the ballpoint pen tends to highlight a few key individuals, most notably the Hungarian journalist László Bíró, who is credited with inventing it. But as with most stories of individual genius, this take obscures a much longer history of iterative engineering and marketing successes. In fact, Bíró wasn’t the first to develop the idea: The ballpoint pen was originally patented in 1888 by an American leather tanner named John Loud, but his idea never went any further. Over the next few decades, dozens of other patents were issued for pens that used a ballpoint tip of some kind, but none of them made it to market.

These early pens failed not in their mechanical design, but in their choice of ink. The ink used in a fountain pen, the ballpoint’s predecessor, is thinner to facilitate better flow through the nib—but put that thinner ink inside a ballpoint pen, and you’ll end up with a leaky mess. Ink is where László Bíró, working with his chemist brother György, made the crucial changes: They experimented with thicker, quick-drying inks, starting with the ink used in newsprint presses. Eventually, they refined both the ink and the ball-tip design to create a pen that didn’t leak badly. (This was an era in which a pen could be a huge hit because it only leaked ink sometimes.)

The Bírós lived in a troubled time, however. The Hungarian author Gyoergy Moldova writes in his book Ballpoint about László’s flight from Europe to Argentina to avoid Nazi persecution. While his business deals in Europe were in disarray, he patented the design in Argentina in 1943 and began production. His big break came later that year, when the British Air Force, in search of a pen that would work at high altitudes, purchased 30,000 of them. Soon, patents were filed and sold to various companies in Europe and North America, and the ballpoint pen began to spread across the world.

October 8, 2015

“[P]harmaceutical companies … make out like bandits from the existence of the patent system”

The current US patent system is set up to create and maintain — for a limited time — monopolies that can be exploited by pharmaceutical companies:

The Wall Street Journal has a puzzling piece complaining about how the pharmaceutical companies seem to make out like bandits from the existence of the patent system. What puzzles is that the entire point and purpose of the patent system, in an economic sense, is so that inventors of things can make out like bandits. The background problem is that of public goods, something I’ll explain in a moment. That problem leads us to thinking that a pure free market in things which are public goods isn’t going to work as well as something a little different. So, we design something a little different. And the point and purpose of our design is so that people who innovate can make vast mountains of cash out of having done so.

It’s then more than a bit odd to point out that our system enables people who innovate to make vast mountains of cash.

[…]

Which brings us to the subtlety of those pricing decisions. With drugs, pharmaceuticals, close enough the cost of manufacturing a dose is zero. All of the costs go in the original research, the clinical testing (the lion’s share) and getting it through the FDA. Profit is therefore determined, since marginal production costs are zero (they’re not, accurately, but close enough for this comparison), by gross revenue. And we want to maximise the incentive for people to innovate, that’s the very reason we’ve got this patent system in the first place, and thus we would rather like the pharma companies to be maximising revenue.

And thus, from this economic point of view, we should be quite happy with people raising their prices. Demand does fall as they do so, yes, but as long as gross revenue increases, the price rises more than compensating for the fall in unit demand, then we should be happy with the way the system is working. Gross revenue is being maximised, profits are being maximised, incentives to innovate are being maximised. That’s what we want our system to do after all.

Far from being worried about this price gouging we should be welcoming it. Because, obviously, someone making bajillions out of having innovated a drug to cure a disease increases the incentives for many other people to go and invest bajillions of their own to cure other diseases. Far from complaining about it we should be celebrating the system working.

Science as horse racing

In Wired, Sarah Zhang handicaps the horses in this year’s highly competitive Nobel Sweepstakes:

Nobel prize speculation, gossip, and betting pools kick off every fall around the time Thomson Reuters releases its predictions for science’s most prestigious prize. This year, one prediction was unusual: a genome-editing tool so hyped that it even got on the cover of WIRED.

(No, seriously, how often does molecular biology get to occupy the same space as Star Wars or Rashida Jones?)

The tool, Crispr/Cas9, is essentially a pair of molecular scissors for editing DNA, so precise and easy to use that it has taken biology by storm. Hundreds if not thousands of labs now use Crispr/Cas9 to do everything from making super-muscled pigs to snipping HIV genes out of infected cells to creating transgenic monkeys for neuroscience research. But the Nobel prediction stands out for two reasons: First, the highly-cited paper describing Crispr/Cas9 came out a mere three years ago, a blip in the timescale of science. Second, the technique is currently at the heart of a bitter patent fight.

Thomson Reuters bases its predictions on how often key papers get cited by other scientists. Here, the paper in question has as its authors Jennifer Doudna, a molecular biologist at UC Berkeley, and Emmanuelle Charpentier, a microbiologist now at the Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology. Missing is Feng Zhang (no relation to this writer), a molecular biologist at the Broad Institute and MIT, who actually owns the patents for CRISPR/Cas9 and says that he came up with the idea independently. So let’s say Thomson Reuters gets it right. Could the patent for a discovery go to one scientist, and the Nobel prize for the discovery to someone else?

The two groups — or their patent lawyers, really — are in fact fighting over credit for CRISPR/Cas9. At stake are millions of dollars already poured into rival companies that have licensed patents from the two different groups.

But putting aside all the lawyers and all the money for a moment, obsessing over finding the one true origin of Crispr/Cas9 gets science all wrong. Casting the narrative as Doudna versus Zhang or Berkeley versus MIT is a misapprehension of history, creativity, and innovation. Discovery comes not from a singular stroke of genius, but an incremental body of research. “I’m not a great believer in the flash-of-genius theory. If you are a historian —” says Mario Biagioli, who is in fact a historian of science at UC Davis — “you quickly will realize exactly how many times there are independent discoveries of the same thing.” The dispute over credit for CRISPR/Cas9 is not the result of exceptional coincidence and disagreement. In fact, it illuminates how science always works.