Marginal Revolution University

Published on 18 Apr 2017This wk: Put your quantity theory of money knowledge to use in understanding the aggregate demand curve.

Next wk: Use your knowledge of the AD curve to dig into the long-run aggregate supply curve.

The aggregate demand-aggregate supply model, or AD-AS model, can help us understand business fluctuations. In this video, we’ll focus on the aggregate demand curve.

The aggregate demand curve shows us all of the possible combinations of inflation and real growth that are consistent with a specified rate of spending growth. The dynamic quantity theory of money (M + v = P + Y), which we covered in a previous video, can help us understand this concept.

We’ll walk you through an example by plotting inflation on the y-axis and real growth on the x-axis — helping us draw an aggregate demand curve!

Next week, we’ll combine our new knowledge on the AD curve with the long-run aggregate supply curve. Stay tuned!

November 23, 2018

The Aggregate Demand Curve

October 13, 2018

Why Governments Create Inflation

Marginal Revolution University

Published on 14 Feb 2017Inflation can carry with it quite a few costs. But some governments, like Zimbabwe under President Robert Mugabe in the early 2000s, will go out of their to way to create inflation. Why?

Well, in the Zimbabwe example, the government printed the money and used it to buy goods and services. The ensuing hyperinflation acted as a tax that transferred wealth from the citizens to the government.

However, this is a fairly uncommon reason. Inflation doesn’t make for a good tax and it’s a last resort for desperate governments that are otherwise unable to raise funds.

There are other benefits to inflation that would make governments want to create it. In the short run, inflation can actually boost economic output. However, as we’ve previously covered, an increase in the money supply leads to an equal increase in prices in the long run.

If there’s a recession, governments might create inflation to spur productivity and ease the economic downturn. However, this type of inflationary boosting can be abused. Long-term boosting causes people to simply expect and prepare for it.

Reducing inflation is also costly. If the process is reversed and the growth in the money supply decreases, we get disinflation. Unemployment will likely increase in the short run and an economy can go through a recession. But in the long run, prices will adjust as well.

Inflation can be a neat trick for governments to boost productivity in an economy. But it can easily get out of hand and has even been likened to a drug. Once you start, you need more and more. And stopping is awfully painful as the economy shrinks.

This concludes our section on Inflation and the Quantity Theory of Money. Up next in Principles of Macroeconomics, we’ll be digging into Business Fluctuations.

September 6, 2018

Costs of Inflation: Price Confusion and Money Illusion

Marginal Revolution University

Published on 2 Feb 2017The inflation rate can be somewhat volatile and unpredictable. For example, let’s take the period between 1964 and 1983 in the U.S. The inflation rate jumped around from 1.3% in 1964 to 5.9% in 1970, and all the way up to 14% in in 1980, before dipping back down to 3% in 1983. These dramatic changes, though still fairly mild in the realm of inflation, caught people off-guard.

Peru’s inflation rates in the late 1980s through the early 1990s were on even more of a rollercoaster. Clocking in at 77% in 1986, its inflation rate was already quite high. But by 1990, it had jumped to 7,500%, only to fall to 73% a mere two years later.

High and volatile inflation rates can wreak havoc on the price system where prices act as signals. If the price of oil rises, it signals scarcity of that product and allows consumers to search for alternatives. But with high and volatile inflation, there’s noise interfering with this price signal. Is oil really more scarce? Or are prices simply rising? This leads to price confusion – people are unsure of what to do and the price system is less effective at coordinating market activity.

Money illusion is another problem associated with inflation. You’ve likely experienced this yourself. Think of something that you’ve noticed has gotten more expensive over the course of your lifetime, such as a ticket to the movies. Is it really that going out the movies has become a pricier activity, or is it the result of inflation? It’s difficult for us to make all of the calculations to accurately compare rising costs. This is known as “money illusion” – or when we mistake a change in the nominal price with a change in the real price.

Inflation, especially when it’s high and volatile, can result in some costly problems for everyone. Next up, we’ll look at how it redistributes wealth and can break down financial intermediation.

August 20, 2018

Causes of Inflation

Marginal Revolution University

Published on 24 Jan 2017In the last video, we learned the quantity theory of money and its corresponding identity equation: M x V = P x Y

For a quick refresher:

•M is the money supply.

•V is the velocity of money.

•P is the price level.

•And Y is the real GDP.

In this video, we’re rewriting the equation slightly to divide both sides by Y and explore the causes behind inflation. What we discover is that a change in P has three possible causes – changes in M, V, or Y.

You probably know that prices can change a lot, even over a short period of time.

Y, or real GDP, tends to change rather slowly. Even a seemingly small jump or fall in Y, such as 10% in a year, would signal astonishing economic growth or a great depression. Y probably isn’t our usual culprit for inflation.

V, or the velocity of money, also tends to be rather stable for an economy. The average dollar in the United States has a velocity of about 7. That may fall or rise slightly, but not enough to influence prices.

That leaves us with M. Changes in the money supply are the driving factor behind inflation. Put simply, when more money chases the same amount of goods and services, prices must rise.

Can we put this theory to the test? Let’s look at some real-world examples and see if the quantity theory of money holds up.

In Peru in 1990, hyperinflation came into full swing. If we track the growth rate of the money supply to the growth rate of prices, we can see that they align almost perfectly on a graph with both clocking in around 6,000% that year.

If we plot the growth rates of the money supply along with the growth rates of prices for a many countries over a long stretch of time, we can see the same relationship.

We’ll wrap-up the causes of inflation with three principles to keep in mind as we continue exploring this topic:

•Money is neutral in the long run: a doubling of the money supply will eventually mean a doubling of the price level.

•“Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomena.” – Milton Friedman

•Central banks have significant control over a nation’s money supply and inflation rate.

August 9, 2018

Quantity Theory of Money

Marginal Revolution University

Published on 17 Jan 2017The quantity theory of money is an important tool for thinking about issues in macroeconomics.

The equation for the quantity theory of money is: M x V = P x Y

What do the variables represent?

M is fairly straightforward – it’s the money supply in an economy.

A typical dollar bill can go on a long journey during the course of a single year. It can be spent in exchange for goods and services numerous times. In the quantity theory of money, how many times an average dollar is exchanged is its velocity, or V.

The price level of goods and services in an economy is represented by P.

Finally, Y is all of the finished goods and services sold in an economy – aka real GDP. When you multiply P x Y, the result is nominal GDP.

Actually, when you multiply M x V (the money supply times the velocity of money), you also get nominal GDP. M x V is equal to P x Y by definition – it’s an identity equation.

You can think about the two sides of the equation like this: the left (M x V) covers the actions of consumers while the right (P x Y) covers the actions of producers. Since everything that is sold is bought by someone, these two sides will remain equal.

Up next, we’ll use the quantity theory of money to discuss the causes of inflation.

July 20, 2018

Fiat currency and the impact of cryptocurrencies

At Catallaxy Files, Sinclair Davidson explains some of the advantages and disadvantages of both fiat (government-issued) and private currency:

As George Selgin, Larry White and others have shown, many historical societies had systems of private money — free banking — where the institution of money was provided by the market.

But for the most part, private monies have been displaced by fiat currencies, and live on as a historical curiosity.

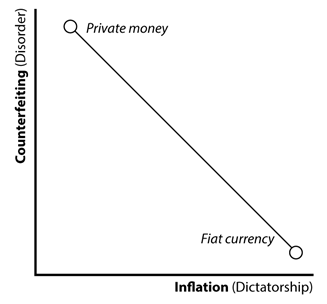

We can explain this with an ‘institutional possibility frontier’; a framework developed first by Harvard economist Andrei Shleifer and his various co-authors. Shleifer and colleagues array social institutions according to how they trade-off the risks of disorder (that is, private fraud and theft) against the risk of dictatorship (that is, government expropriation, oppression, etc.) along the frontier.

As the graph shows, for money these risks are counterfeiting (disorder) and unexpected inflation (dictatorship). The free banking era taught us that private currencies are vulnerable to counterfeiting, but due to competitive market pressure, minimise the risk of inflation.

By contrast, fiat currencies are less susceptible to counterfeiting. Governments are a trusted third party that aggressively prosecutes currency fraud. The tradeoff though is that governments get the power of inflating the currency.

The fact that fiat currencies seem to be widely preferred in the world isn’t only because of fiat currency laws. It’s that citizens seem to be relatively happy with this tradeoff. They would prefer to take the risk of inflation over the risk of counterfeiting.

One reason why this might be the case is because they can both diversify and hedge against the likelihood of inflation by holding assets such as gold, or foreign currency.

The dictatorship costs of fiat currency are apparently not as high as ‘hard money’ theorists imagine.

Introducing cryptocurrencies

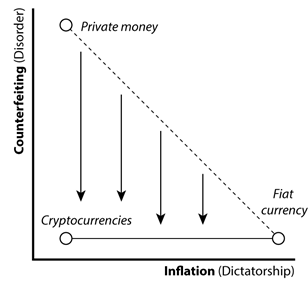

Cryptocurrencies significantly change this dynamic.

Cryptocurrencies are a form of private money that substantially, if not entirely, eliminate the risk of counterfeiting. Blockchains underpin cryptocurrency tokens as a secure, decentralised digital asset.

They’re not just an asset to diversify away from inflationary fiat currency, or a hedge to protect against unwanted dictatorship. Cryptocurrencies are a (near — and increasing) substitute for fiat currency.

This means that the disorder costs of private money drop dramatically.

In fact, the counterfeiting risk for mature cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin is currently less than fiat currency. Fiat currency can still be counterfeited. A stable and secure blockchain eliminates the risk of counterfeiting entirely.

July 7, 2018

Zimbabwe and Hyperinflation: Who Wants to Be a Trillionaire?

Marginal Revolution University

Published on 3 Jan 2017How would you like to pay $417.00 per sheet of toilet paper?

Sound crazy? It’s not as crazy as you may think. Here’s a story of how this happened in Zimbabwe.

Around 2000, Robert Mugabe, the President of Zimbabwe, was in need of cash to bribe his enemies and reward his allies. He had to be clever in his approach, given that Zimbabwe’s economy was doing lousy and his people were starving. Sow what did he do? He tapped the country’s printing presses and printed more money.

Clever, right?

Not so fast. The increase in money supply didn’t equate to an increase in productivity in the Zimbabwean economy, and there was little new investment to create new goods. So, in effect, you had more money chasing the same goods. In other words, you needed more dollars to buy the same stuff as before. Prices began to rise — drastically.

As prices rose, the government printed more money to buy the same goods as before. And the cycle continued. In fact, it got so out of hand that by 2006, prices were rising by over 1,000% per year!

Zimbabweans became millionaires, but a million dollars may have only been enough to buy you one chicken during the hyperinflation crisis.

It all came crashing down in 2008 when — given that the Zimbabwean dollar basically ceased to exist — Mugabe was forced to legalize transactions in foreign currencies.

Hyperinflation isn’t unique to Zimbabwe. It has occurred in other countries such as Yugoslavia, China, and Germany throughout history. In future videos, we’ll take a closer look at inflation and what causes it.

June 29, 2018

QotD: What is a discount rate?

It is not the 20 percent savings you got by buying a new washing machine on Black Friday last year. A discount rate is a way of accounting for the fact that dollars in the future are not quite the same as dollars you have right now.

You know this, don’t you? Imagine I offered to give you a dollar right now, or a dollar a year from now. You don’t have to think hard about that decision, because you know instinctively that the dollar that’s right there, able to be instantly transferred into your sweaty little hand, is much more valuable. It can, in fact, be easily transformed into a dollar a year from now, by the simple expedient of sticking it in a drawer and waiting. It can also, however, be spent before then. It has all the good stuff offered by a dollar later, plus some option value.

Even if you’re sure you don’t want to spend it in the next year, however, a dollar later is not as good as a dollar now, because it’s riskier. That dollar I’m holding now can be taken now, and then you will definitely have it. If you’re counting on getting a dollar from me a year from now, well, maybe I’ll die, or forget, or go bankrupt.

The point is that if you’re valuing assets, and some of your assets are dollars you actually have, and others are dollars that someone has promised to give to you at some point in the future, you should value the dollars you have in your possession more highly than dollars you’re supposed to get later.

The rule for establishing an exchange rate between future dollars and current ones is known as the “discount rate.” Basically, it’s a steady annual percentage by which you lower the value of dollars you get in future years.

All you need to remember is two things: the longer you have to wait to get paid, the less that promise is worth to you today. And the higher the discount rate you apply, the lower you’re valuing that future dollar.

Megan McArdle, “Public Pensions Are Being Overly Optimistic”, Bloomberg View, 2016-09-21.

May 12, 2018

Cryptocurrency scammers

A high proportion of initial coin offerings are nothing but scammers doing what scammers do best, says Nouriel Roubini:

Initial coin offerings have become the most common way to finance cryptocurrency ventures, of which there are now nearly 1,600 and rising. In exchange for your dollars, pounds, euros, or other currency, an ICO issues digital “tokens,” or “coins,” that may or may not be used to purchase some specified good or service in the future.

Thus it is little wonder that, according to the ICO advisory firm Satis Group, 81% of ICOs are scams created by con artists, charlatans, and swindlers looking to take your money and run. It is also little wonder that only 8% of cryptocurrencies end up being traded on an exchange, meaning that 92% of them fail. It would appear that ICOs serve little purpose other than to skirt securities laws that exist to protect investors from being cheated.

If you invest in a conventional (non-crypto) business, you are afforded a variety of legal rights – to dividends if you are a shareholder, to interest if you are a lender, and to a share of the enterprise’s assets should it default or become insolvent. Such rights are enforceable because securities and their issuers must be registered with the state.

Moreover, in legitimate investment transactions, issuers are required to disclose accurate financial information, business plans, and potential risks. There are restrictions limiting the sale of certain kinds of high-risk securities to qualified investors only. And there are anti-money-laundering (AML) and know-your-customer (KYC) regulations to prevent tax evasion, concealment of ill-gotten gains, and other criminal activities such as the financing of terrorism.

In the Wild West of ICOs, most cryptocurrencies are issued in breach of these laws and regulations, under the pretense that they are not securities at all. Hence, most ICOs deny investors any legal rights whatsoever. They are generally accompanied by vaporous “white papers” instead of concrete business plans. Their issuers are often anonymous and untraceable. And they skirt all AML and KYC regulations, leaving the door open to any criminal investor.

Of course, for a significant number of people, not having the state involved in their investment is an attraction rather than a drawback. And not just criminals, but people who live in jurisdictions with uncertain reliance on the rule of law (not to mention Russia by name), where property rights are not so much “rights” as “privileges to the right sort of people”.

December 27, 2017

Will Hutton mansplains Blockchain … as he understands it

Tim Worstall tries to mitigate the damage caused by Will Hutton’s amazing misunderstanding of what blockchain technology is:

Will Hutton decides to tell us all how much Bitcoin and the blockchain is going to change our world:

Blockchain is a foundational digital technology that rivals the internet in its potential for transformation. To explain: essentially, “blocks” are segregated, vast bundles of data in permanent communication with each other so that each block knows what the content is in the rest of the chain. However, only the owner of a particular block has the digital key to access it.

So what? First, the blocks are created by “miners”, individual algorithm writers and companies throughout the world (with a dense concentration in China), who want to add a data block to the chain.

Will Hutton is, you will recall, one of those who insists that the world should be planned as Will Hutton thinks it ought to be. Something which would be greatly aided if Will Hutton had the first clue about the world and the technologies which make it up.

Blocks aren’t created by miners and individual algorithm writers, there is the one algo defined by the system and miners are confirming a block, not creating it. The blocks are not in communication with each other, they do not know what is in the rest of the chain – absolutely not in the case of earlier blocks knowing what is in later. It’s simply a permanent record of all transactions ever undertaken with an independent checking mechanism.

It’s entirely true that this could become very useful. But it’s really not what Hutton seems to think it is.

December 22, 2017

Remy: Bitcoin Billionaire

ReasonTV

Published on 21 Dec 2017Remy rides crypto to the moon.

—–

Written and performed by Remy. Produced by Austin and Meredith Bragg. Music tracks mastered by Ben Karlstrom. Music by J-Beats Productions.

Lyrics:

I was broke, unemployed, I was starting to slouch

I was sleeping in the basement on my momma’s new couch

That’s when I heard it all, a chance to skirt it all a money like my last girl

Completely virtual…Got the top graphics cards, got a power supply

a microprocesser, a motherboard, a towering drive

I put the RAM in the RAM slot, drive in the larger bay

topped it off, two fans

Like a Chargers game!Price spike to $30!? I missed out, I fear

crudely assemble a rig like a BP engineer

My friends and family smile and smirk and all make fun of me

But I’m-a make them eat their words because I’m gonna be aBitcoin Billionaire

Spending money like I don’t care

Mining coin in my underwear

I’m gonna be a Bitcoin BillionaireSelecting software and reading the notes

I’m picking out my favorite miners like a Penn State coach

Pick me a digital wallet for holding all my amounts

read up on the all the ways to open lots of accounts I feel like Tom Brady,I got a fear of inflation

But this is crypto, baby — central bank decentralization

The script I flipped it, laptop encrypted

My life was rotten now all my cotton’s Egypt-edNow even on my vacation I’m crypto-supplying

They call me gentrification the way I’m block-modifying

Friends asking “what’s the best part of your newfound treasury?”

I say “reminding you how you told me I’d never be a…Bitcoin Billionaire

Spending money like I don’t care

Flash drives in their underwear

Now that I’m a Bitcoin BillionaireThe cash was never-ending, yo

upscale and fun and rowdy

I was spending like a 7 on a

scale from 1 to SaudiCall it mad bankin’, all night and all weekend

My rig is Al Franken:

(grabs what it can while you sleepin’)Just try outspending me and you’ll see I’m on a mission

I drop more Satoshis than a clumsy Japanese obstetrician

But I ain’t open to splits, don’t care if it’s best or not

Opposing forks like a Chinese restaurantI went from geek to chic, from basic to ASIC

I went from basement-squatting to yachting from basin to basin

Went from no friends and depression to peer-to-peer legendBitcoin Billionaire

Spending money like I don’t care

Then one day there was a solar flare…I was a Bitcoin Billionaire

Spending money like I don’t care

Now I just pawned my underwear

Used to be a Bitcoin Billionaire.

November 30, 2017

Bitcoin

Charles Stross explains why he’s not a fan of Bitcoin (and I do agree with him that the hard limit to the total number of Bitcoins sounded like a bad idea to me the first time I ever heard of them):

So: me and bitcoin, you already knew I disliked it, right?

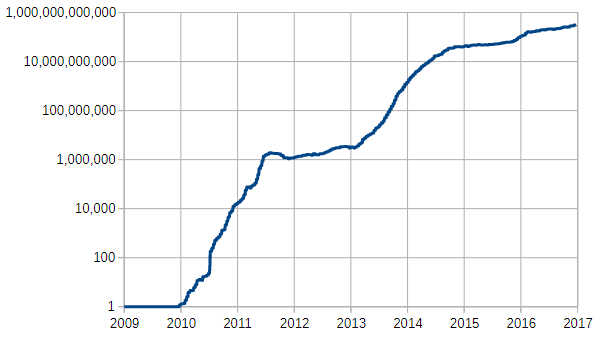

(Let’s discriminate between Blockchain and Bitcoin for a moment. Blockchain: a cryptographically secured distributed database, useful for numerous purposes. Bitcoin: a particularly pernicious cryptocurrency implemented using blockchain.) What makes Bitcoin (hereafter BTC) pernicious in the first instance is the mining process, in combination with the hard upper limit on the number of BTC: it becomes increasingly computationally expensive over time. Per this article, Bitcoin mining is now consuming 30.23 TWh of electricity per year, or rather more electricity than Ireland; it’s outrageously more energy-intensive than the Visa or Mastercard networks, all in the name of delivering a decentralized currency rather than one with individual choke-points. (Here’s a semi-log plot of relative mining difficulty over time.)

Bitcoin relative mining difficulty chart with logarithmic vertical scale. Relative difficulty defined as 1 at 9 January 2009. Higher number means higher difficulty. Horizontal range is from 9 January 2009 to 8 November 2014.

Source: Wikipedia.Credit card and banking settlement is vulnerable to government pressure, so it’s no surprise that BTC is a libertarian shibboleth. (Per a demographic survey of BTC users compiled by a UCL researcher and no longer on the web, the typical BTC user in 2013 was a 32 year old male libertarian.)

Times change, and so, I think, do the people behind the ongoing BTC commodity bubble. (Which is still inflating because around 30% of BTC remain to be mined, so conditions of artificial scarcity and a commodity bubble coincide). Last night I tweeted an intemperate opinion—that’s about all twitter is good for, plus the odd bon mot and cat jpeg—that we need to ban Bitcoin because it’s fucking our carbon emissions. It’s up to 0.12% of global energy consumption and rising rapidly: the implication is that it has the potential to outstrip more useful and productive computational uses of energy (like, oh, kitten jpegs) and to rival other major power-hogging industries without providing anything we actually need. And boy did I get some interesting random replies!

November 18, 2017

QotD: A key drawback of a cashless society

When I was just starting out as a journalist, the State of New York swooped down and seized all the money out of one of my bank accounts. It turned out — much later, after a series of telephone calls — that they had lost my tax return for the year that I had resided in both Illinois and New York, discovered income on my federal tax return that had not appeared on my New York State tax return, sent some letters to that effect to an old address I hadn’t lived at for some time, and neatly lifted all the money out of my bank. It took months to get it back.

I didn’t starve, merely fretted. In our world of cash, friends and family can help out someone in a situation like that. In a cashless society, the government might intercept any transaction in which someone tried to lend money to the accused.

Unmonitored resources like cash create opportunities for criminals. But they also create a sort of cushion between ordinary people and a government with extraordinary powers. Removing that cushion leaves people who aren’t criminals vulnerable to intrusion into every remote corner of their lives.

We probably won’t notice how much this power grows every time we swipe a card instead of paying cash. The danger is that by the time we do notice, it will be too late. If we want to move toward a cashless society — and apparently we do — then we also need to think seriously about limiting the ability of the government to use the payments system as an instrument to control the behavior of its citizens.

Megan McArdle, “After Cash: All Fun and Games Until Somebody Loses a Bank Account”, Bloomberg View, 2016-03-15.

November 15, 2017

QotD: Some positive effects of a cashless society

There’s a lot to like about the idea of a cashless society, starting with its effect on crime. The payoff to mugging people or snatching their bags has already declined dramatically, simply because fewer and fewer people are carrying cash around. I myself almost never have any of the stuff on hand. If it weren’t for the rising value of mobile phones, street crime would have largely lost its profit motive … and if better phone security makes it impossible to repurpose a stolen phone, that motive will approach zero.

A cashless society would also see a decline in the next level of robberies: stickups of retail outlets. There’s obviously no point in sticking a gun in the face of some liquor store clerk when all he can give you is the day’s credit card receipts. Even if these sorts of crimes are replaced by electronic thefts of equivalent value, this would still be a major improvement for society, simply because the threat of violent crime is uniquely terrifying and corrosive to community.

One step beyond that, there’s the effect on criminal enterprises, for whom cash is key. Making it impossible to transact business while keeping large amounts of money away from the watchful eye of the government will make it much harder to run an illegal operation. And while I love the tales of quirky bootleggers and tramp peddlers as much as the next fellow, the truth is that large criminal organizations are full of not very nice people, doing not very nice things, and it would be better for society if they stopped.

Megan McArdle, “After Cash: All Fun and Games Until Somebody Loses a Bank Account”, Bloomberg View, 2016-03-15.

November 5, 2017

The decline of the (western) Roman empire

Richard Blake considers some of the popular explanations for the slow decline of the Roman empire in the west:

The Empire was an agglomeration of communities which were illiterate to an extent unknown in Western Europe since about 1450. Even most officers in the bureaucracy were at best semi-literate. There was no printing press. Writing materials were very expensive – one sheet of papyrus cost about £100 in today’s money. Cheaper materials were still expensive and were of little use for other than ephemeral use. Central control was usually notional, and the more effective Emperors – Hadrian, Diocletian, et al – were those who spent much of their time touring the Empire to supervise in person.

The economic legislation of the Emperors was largely unenforceable. Some effort was made to enforce the Edict of Maximum Prices. But this appears to have been sporadic, and it lasted only between 301 and 305, when Diocletian abdicated. The Edict’s main effect was to leave a listing of relative prices for economic historians to study 1,500 years later.

As for inflation, it can be doubted how far outside the cities a monetary economy existed. This is not to doubt whether the laws of supply and demand operated, only whether most transactions were not by barter at more or less customary ratios of exchange. This being so, the debasement of the silver coinage would have had less disruptive effect than the silver inflation in Europe of the sixteenth century. Also, the gold coinage was stabilised over a hundred years before the Western military collapse of the fifth century. And the military crisis of the late third century was overcome while the inflation continued.

Nor is there any evidence that people left the cities in large numbers for the countryside. The truth seems to be that the Roman Empire was afflicted, from the middle of the second century, by a series of epidemic plagues, possibly brought on by global cooling, that sent populations into a decline that continued until about the eighth century. The cities shrank not because their inhabitants left them, but because they died. So far as they were enforced, the Imperial responses to population decline made things worse, but were not the ultimate cause of decline. Where population decline was less severe, there was no economic decline. Whenever the decline went into temporary reverse – as it may have in the fifth century in the East – economic activity recovered.

Von Mises is right that the barbarian invasions were not catastrophic floods that destroyed everything in their path. They were incursions by small bands. What made them irreversible was that they took place in the West into a demographic vacuum that would have existed regardless of what laws the Emperors made.