Ed West considers the time-honoured Ottoman habit of strangling the new Sultan’s half-brothers on his accession to the throne and notes that after the practice was discontinued, many notables in the empire thought it also marked a down-turn in the quality of later Sultans. The British crown never had such a formal tradition, although brotherly love seems to have been in very short supply a thousand years ago:

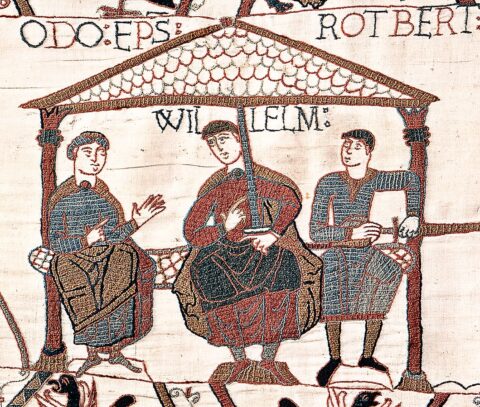

Panel from the Bayeux Tapestry – this one depicts Bishop Odo of Bayeux, Duke William, and Count Robert of Mortain.

Scan from Lucien Musset’s The Bayeux Tapestry via Wikimedia Commons.

Tales of royal brothers at war are a common theme, a staple of Norse sagas in particular, a recent example being the television series Vikings, and the brothers Ragnar and Rollo. William and Harry’s own family story in England begins with a tale told in one 14th century Icelandic saga, Hemings þáttr, which draws on older Norwegian stories to recall two royal brothers who became deadly rivals, Harold and Tostig.

Harold, as Earl of Wessex and the second most powerful man in England, had had his brother installed as Earl of Northumbria, where he had made himself immensely unpopular and provoked an uprising. When in 1065 Harold did a deal with the northerners to remove his sibling — presumably in exchange for the Northumbrians supporting his claim to the throne when the ailing King Edward passed away — Tostig fled abroad, embittered and determined to get revenge. Later accounts suggest that Harold and Tostig were rivals from an early age, one story having the young brothers fighting at the royal court as youngsters. Who knows, maybe Harold got the bigger room.

Tostig, now an exile, travelled around the North Sea looking for someone to help him invade England, finally finding his man with the terrifying Norwegian giant Harald Hardraada. Tostig had told all the Norwegians he was popular back home, but when they arrived in York they found that their English ally was in fact widely despised, and that not a single person came out to greet the former earl.

Tostig was killed soon after, in battle with his brother, having first (supposedly) exchanged words in this legendary meeting.

Harold himself would follow soon, victim of the English aristocracy’s great forefather William the Conqueror, whose success is illustrated by the naming patterns that followed. Harold’s brothers were Sweyn, Tostig, Gyrth, Leofwine and Wulfnoth; the Conqueror’s sons Robert, Richard, William and Henry. We haven’t had any Prince Wulfnoths recently.

The Conqueror’s son Richard having died in a hunting accident, the surviving Norman brothers had similarly fallen out, by one account the feud starting with a practical joke where William and Henry had poured a bucket of urine over eldest brother Robert. But mainly it was over land and power: after their father’s death Robert was made Duke of Normandy, the middle brother became William II of England, while Henry had to make do with just a cash payment.

Yet when William died in a mysterious hunting accident in the New Forest in 1100, Henry was conveniently close enough to reach the Treasury at Winchester within an hour to claim the crown. Six years later he invaded Normandy, with a partly English army, and captured his surviving brother, keeping Robert imprisoned for the rest of his life.

Henry I ruled for 35 years, but his long reign was followed by a civil war between his daughter Matilda and nephew Stephen, resulting in the rise of a new dynasty, the House of Anjou, or Plantagenets — so defined by internal conflict that Francis Bacon called them “a race much dipped in their own blood”.

Matilda’s husband Geoffrey Plantagenet had his brother Elias imprisoned, and Geoffrey’s son, King Henry II, had also gone to war with his younger brother, also Geoffrey. Even Geoffrey Plantagenet’s grandfather Fulk “the Quarreller” had spent over 30 years fighting for control of the county with his older brother, yet another Geoffrey.

Henry II in contrast fought his four sons and, after his death, his heir Richard I would also face rebellion from his younger brother John. When the Lionheart returned from crusade to deal with his deeply unlovable sibling he was remarkably forgiving, telling him: “Think no more of it, brother: you are but a child who has had evil counsellors.” This was despite John being 27 at the time.

More than two centuries later the House of Plantagenet came crashing down with a war pitting cousin against cousin, although brothers also fell out in the form of Edward IV and George, Duke of Clarence.

Both men were tall, blond and handsome, and both had a cruel and violent streak, but here the younger brother was impulsive, vain and foolish. He lacked maturity or self-control, was easily flattered and tempted into unwise decisions. He had been given vast estates and a lavish household but resented his older brother, who had also blocked his marriage to the daughter of the country’s largest landowner.

So Clarence had joined in the overthrow of Edward in 1470, while the youngest brother Richard, Duke of Gloucester, had remained loyal. However, when Edward returned to England the following March and Clarence led 4,000 men out to fight him, he was talked into changing sides again.

Clarence was forgiven, but the two brothers looked upon each other “with no very fraternal eyes”, and five years later he seems to have lost his mind after his wife died during childbirth. He accused the king of “necromancy” and of poisoning his subjects, and when brought before his brother made things much worse by claiming that Edward was a bastard. He was put to death.

Apparently, a soothsayer had also told King Edward that “G” would take his crown, and this must have fuelled his paranoia about George; after all, his other brother, the loyal Richard of Gloucester, would never do such a thing.

Such fraternal feuding ended with the rise of the Tudors and the conflicts between the House of Stuart and Parliament. There would be no more point in younger brothers threatening the monarch because the monarch no longer really had power; the royal family had evolved into a business, “the firm”, one in which hierarchies were clear and immovable, and the fortunes of family members were clearly joined.