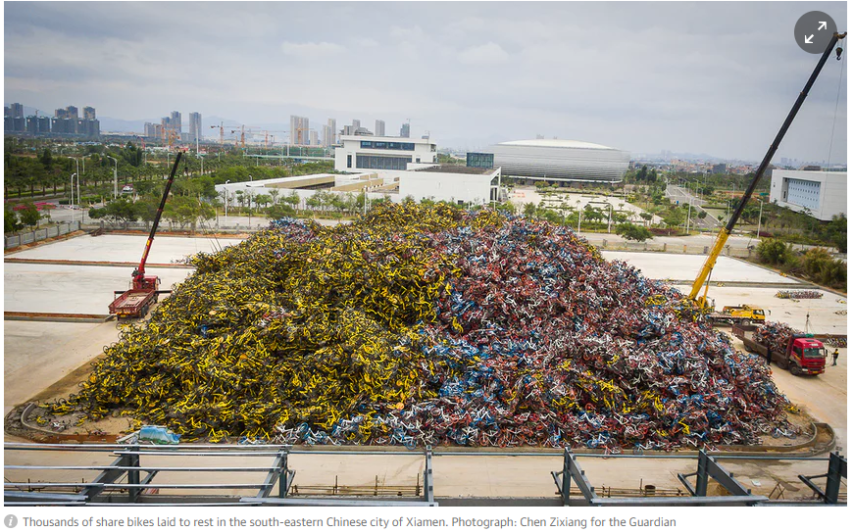

In the Guardian, Benjamin Haas reports on what at first might seem to be a vast modern art display:

At first glance the photos vaguely resemble a painting. On closer inspection it might be a giant sculpture or some other art project. But in reality it is a mangled pile of bicycles covering an area roughly the size of a football pitch, and so high that cranes are need to reach the top; cast-offs from the boom and bust of China’s bike sharing industry.

Just two days after China’s number three bike sharing company went bankrupt, a photographer in the south-eastern city of Xiamen captured a bicycle graveyard where thousands have been laid to rest. The pile clearly contains thousands of bikes from each of the top three companies, Mobike, Ofo and the now-defunct Bluegogo.

Tim Worstall draws the correct conclusion from the provided evidence:

We want, irrespective of anything else about the economy, a method of testing ideas to see if they work. Does the application of these scarce resources meet some human need or desire? Does it do so more than an alternative use, is it even adding value at all?

Bike shares, are they a good idea or not? The underlying problem being that expressed and revealed preferences aren’t the same. There’s only so far market research can take you, at some point someone, somewhere, has to go out and do it and see.

Excellent, the Commie Chinese have done so. Vast amounts of capital thrown into this, competing bike share companies, hire costs pennies. And no fucker seems very interested. That is, no, large scale bike share schemes don’t meet any discernible human need or desire, they don’t add value, spending the money on something else will increase human joy and happiness better.

And this is excellent, we’ve tried the idea and it don’t work. Now we can abandon it and go off and do something else therefore.

Which is the great joy of market based systems. They’re the best method we’ve got of finding out which ideas are fuck ups.

Long live markets.