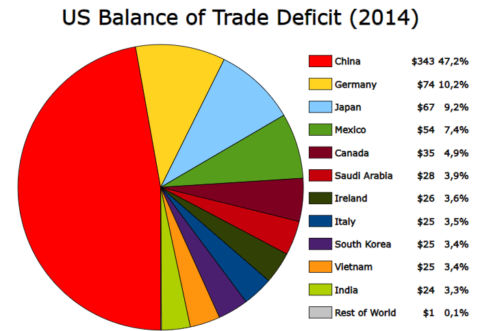

David Friedman discusses how, for example, the US and China manage their trading relationship:

“United States Balance of Trade Deficit-pie chart” by Shirishag75 is marked with CC0 1.0 .

I recently read a thread about US/China trade on a forum occupied mostly by intelligent people. As best I could tell, all participants were taking it for granted that things that make it more expensive to produce in the US, such as regulations or minimum wage laws, make the US “less competitive”, increase the trade deficit, give the Chinese an advantage. Reading Project 2025, the Heritage Foundation’s battle plan for a future conservative president, I observed the same pattern, with only one exception.

It did not seem to have occurred to any of the forum posters that US costs are in dollars, Chinese costs in Yuan, and what determines the exchange rate between them is the cost of producing things. Discussing trade policy in terms of absolute advantage, pre-Ricardian economics, isn’t quite as bad as discussing the space program on the assumption that the Earth is at the center of the universe with sun, moon and planets embedded in a set of nested crystalline spheres surrounding it — Copernicus was about three centuries earlier than Ricardo — but it is close. It is a point that I made here about a year ago, but since the question came up in my most recent post and in a thread on my favorite forum, it is probably worth making again.

The Economics of Trade

It is easiest to start with the simple case of two countries and no capital flows. The only reason Americans want to buy yuan with dollars is to buy Chinese goods, the only reason Chinese want to sell yuan for dollars is to buy American goods. If Americans try to buy more yuan than Chinese want to sell, the price of yuan in dollars goes up, if Chinese want to sell more yuan than Americans want to buy, the price goes down, just as in other markets. The price of yuan in dollars, the exchange rate, ends up at the price at which supply equals demand, which means that Americans are importing the same dollar (and yuan) value of goods that they are exporting.

Suppose the US government, inspired by the mercantilist view that countries get rich by exporting more than they import, tries to produce a “favorable” balance of trade by imposing a tariff on Chinese imports. Chinese goods are now more expensive to Americans. Since they want to buy less from China they don’t need as many yuan so the demand for yuan goes down, the price of yuan in dollars goes down, which reduces the cost of Chinese goods to Americans. Just as before, the exchange rate ends up at a level at which the dollar value of US exports equals the dollar value of US imports. Both imports and exports are now less, since trade is being taxed, but the balance of trade is exactly what it would be without the tariff.

Suppose the US becomes less good at making things due to an increase in government regulation or some other cause. Dollar prices of US goods in the US go up. That makes US goods more expensive to Chinese purchasers so they buy fewer of them, decreasing the demand for dollars on the dollar/yuan market. The exchange rate shifts — dollars are now less valuable so their price falls. Trade still balances. The US is not “less competitive”, merely poorer.

Now add in more countries. One reason Chinese want to buy dollars is to sell them to Germans who want dollars with which to buy American goods. We end up with a trade deficit with China, since some of the dollars they get for their exports are being used to import goods from Germany instead of the US, but a matching trade surplus with Germany, since they are using both the dollars they get by selling things to us and the dollars they get from China to buy goods from us. The same logic applies with more countries.

To explain how it is possible for the US to have a trade deficit we now drop the assumption of no capital movements. One reason Chinese want dollars is to buy goods and ship them to China but another is to buy assets in America — government bonds, shares of stock, real estate. Dollars bought and dollars sold are still equal but exports of goods no longer equal imports of goods. Part of what the US is “exporting”, selling to foreigners, is assets located in the US.

Suppose the US government wants to reduce the trade deficit. One way would be to reduce the budget deficit, since if the US is borrowing less it will not have to pay lenders as high an interest rate, which will make US bonds less attractive to Chinese buyers. Another way would be to block capital movements, make it illegal for foreign buyers to buy US assets. Doing that, however, means less capital investment in the US, hence higher interest rates. With fewer lenders to buy US bonds, the government will have to offer a higher interest rate to sell them.

One argument sometimes offered for restricting foreign investment is that if the Chinese own a lot of US assets that gives them power over us. The same argument was offered in the early 19th century when European investors were paying to build railroads and dig canals in the US. Daniel Webster pointed out that, if there was a conflict with European powers, their assets were sitting on our territory under our control. It wasn’t like they could repossess the Erie canal.

What about imposing a tariff in order to reduce imports? The logic of the previous argument still applies — the exchange rate will shift to make imports more attractive, exports less. Any effect on the deficit will depend on what happens to the attractiveness of US assets to Chinese investors. Figuring out the net effect is complicated, depending in part on what people expect trade policy and exchange rates to be when they collect on their capital investments.