On May 30th 1940, just after the war cabinet crisis & during the Dunkirk evacuation;

Winston Churchill was informed by the Canadian Prime Minister, Mackenzie King, of more dreadful news.

Roosevelt had no faith in Churchill nor Britain, and wanted Canada to give up on her.

Roosevelt thought that Britain would likely collapse, and Churchill could not be trusted to maintain her struggle.

Rather than appealing to Churchill’s pleas of aid — which were politically impossible then anyway — Roosevelt sought more drastic measures.

A delegation was summoned [from] Canada.

They requested Canada to pester Britain to have the Royal Navy sent across the Atlantic, before Britain’s seemingly-inevitable collapse.

Moreover, they wanted Canada to encourage the other British Dominions to get on board such a plan.

Mackenzie King was mortified. Writing in his diary,

“The United States was seeking to save itself at the expense of Britain. That it was an appeal to the selfishness of the Dominions at the expense of the British Isles. […] I instinctively revolted against such a thought. My reaction was that I would rather die than do aught to save ourselves or any part of this continent at the expense of Britain.”

On the 5th June 1940, Churchill wrote back to Mackenzie King,

“We must be careful not to let the Americans view too complacently prospect of a British collapse, out of which they would get the British Fleet and the guardianship of the British Empire, minus Great Britain. […]

Although President [Roosevelt] is our best friend, no practical help has been forthcoming from the United States as yet.”

Another example of the hell Churchill had to endure — which would have broken every lesser man.

Whilst the United States heroically came to aid Britain and her Empire, the initial relationship between the two great powers was different to what is commonly believed.

(The first key mover that swung Roosevelt into entrusting Churchill to continue the struggle — and as such aid would not be wasted on Britain — was when Churchill ordered the Royal Navy’s Force H to open fire and destroy the French Fleet at Mers-el-Kébir — after Admiral Gensoul had refused the very reasonable offers from Britain, despite Germany and Italy demanding the transference of the French Fleet as part of the armistices.)

Andreas Koreas, Twitter, 2024-12-27.

March 30, 2025

QotD: FDR, Mackenzie King and Churchill in 1940

March 4, 2025

FDR – behind closed doors – was as bad as Trump while the Dunkirk evacuation was going on

Winston Churchill became prime minister of Britain the same day the Germans launched their attack against France and the Low Countries in May, 1940. The situation went from bad to appalling in very short order as the vaunted French army’s high command crumbled under the stress (even if the soldiers fought bravely in most cases). The British Expeditionary Force retreated with the French mobile forces toward the English Channel, eventually evacuating as many troops as they could from the port of Dunkirk. During this time, Churchill was appealing to the American President Franklin D. Roosevelt for whatever aid he could send.

Postwar histories tended to portray FDR as both benevolent and helpful toward Churchill in this stressful period, but behind closed doors FDR was far less a future ally, as Andreas Koureas explained on Twitter:

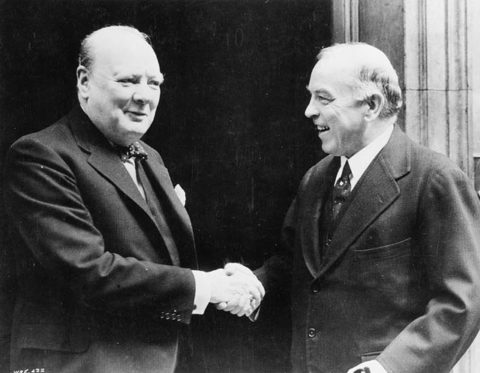

More than a year after FDR’s attempt to pry Canada and the Royal Navy away from a “dying” Britain, he and Churchill met onboard HMS Prince of Wales, in Placentia Bay, Newfoundland, during the Atlantic Charter Conference. President Franklin D. Roosevelt (left) and Prime Minister Winston Churchill are seated in the foreground. Standing directly behind them are Admiral Ernest J. King, USN; General George C. Marshall, U.S. Army; General Sir John Dill, British Army; Admiral Harold R. Stark, USN; and Admiral Sir Dudley Pound, RN. At far left is Harry Hopkins, talking with W. Averell Harriman.

US Naval Historical Center Photograph #: NH 67209 via Wikimedia Commons.

Ironically, the truth is that in 1940, Roosevelt — behind closed doors — behaved worse than Trump.

On the 20th May 1940, after multiple failed pleas for aid, Churchill wrote to Roosevelt that:

“If members of the present administration were finished and others came in to parley amid the ruins, you must not be blind to the fact that the sole remaining bargaining counter with Germany would be the fleet, and if this country was left by the United States to its fate no one would have the right to blame those then responsible if they made the best terms they could for the surviving inhabitants. Excuse me, Mr. President, putting this nightmare bluntly.”

Roosevelt’s refusal for aid was understandable given the political situation in America. As he told Churchill earlier that month, it wasn’t “wise for that suggestion to be made to the Congress at this moment”.

However, what he did after the 20th May telegram wasn’t.

Not bothering to even reply to Churchill’s warnings, Roosevelt instead sought to get Canada to give up on Britain.

As Roosevelt thought that Britain would likely collapse, and Churchill could not be trusted to maintain the struggle, he summoned a delegation for Canada.

The aim was to get Canada to pester Britain to have the Royal Navy sent across the Atlantic, before Britain’s seemingly-inevitable collapse.

Furthermore, to ensure this, the Americans wanted Canada to encourage the other British Dominions to get on board such a plan, and likewise gang up against Britain.

You can see Mackenzie King’s (PM of Canada) disbelief and horror in his diary,

“The United States was seeking to save itself at the expense of Britain. That it was an appeal to the selfishness of the Dominions at the expense of the British Isles. […] I instinctively revolted against such a thought. My reaction was that I would rather die than do aught to save ourselves or any part of this continent at the expense of Britain.”

King telegrammed Churchill on the 30th May that this was the closed-door political situation across the Atlantic.

Bear in mind, Roosevelt was trying to instigate this during the Dunkirk evacuations.

How Churchill didn’t break knowing the one ally he needed in his darkest hour thought he’d fail, I have no idea.

On the 5th June 1940, Churchill wrote back to Mackenzie King,

“We must be careful not to let the Americans view too complacently prospect of a British collapse, out of which they would get the British Fleet and the guardianship of the British Empire, minus Great Britain. […] Although President [Roosevelt] is our best friend, no practical help has been forthcoming from the United States as yet.”

(The first key mover that swung Roosevelt into entrusting Churchill to continue the struggle — and as such aid would not be wasted on Britain — was when Churchill ordered the Royal Navy’s Force H to open fire and destroy the French Fleet at Mers-el-Kébir — after Admiral Gensoul had refused the very reasonable offers from Britain, despite Germany and Italy demanding the transference of the French Fleet as part of the armistices.)

October 25, 2024

How a Soviet Clerk Took Down a Spy Network

World War Two

Published 24 Oct 2024Igor Gouzenko, a Soviet cipher clerk in Canada, defected in 1945, bringing with him documents that revealed a massive Soviet espionage network in the West. His actions forced the world to confront Soviet infiltration, shifting global politics and igniting early Cold War tensions. This episode uncovers how one man’s bravery exposed a hidden war.

(more…)

August 12, 2023

Churchill and India

Andreas Koureas posted an extremely long thread on Twitter, outlining the complex situation he and his government faced during the Bengal Famine of 1943, along with more biographical details of Churchill’s views of India as a whole (edits and reformats as needed):

The most misunderstood part of Sir Winston Churchill’s life is his relationship with India. He neither hated Indians nor did he cause/contribute to the Bengal Famine. After reading through thousands of pages of primary sources, here’s what really happened.

A thread 🧵

I’ve covered this topic before, but in a recent poll my followers wanted a more in-depth thread. Sources are cited at the end. I’m also currently co-authoring a paper for a peer reviewed journal on the subject of the Bengal Famine, which should hopefully be out later this year.

I’ll first address the Bengal Famine (as that is the most serious accusation) and then Churchill’s general views on India. It goes without saying that there will be political activists who will completely ignore what I have to say, as well as the primary sources I’ll cite. I have no doubt, that just like in the past, there will be those who accuse me of only using “British sources”.

This is not true. I have primary sources written by Indians as well as papers by Indian academics.

Moreover, I have no doubt that such activists will, choose to “cite” the ahistorical journalistic articles from The Guardian or conspiratorial books like Churchill’s Secret War by Mukerjee — a debunked book that ignores most of what I’m about to write about, and is really what sparked the conspiracy of Churchill and the Bengal Famine. For everyone else, I hope you find this thread useful.

(more…)

June 28, 2023

How to Fund a War: Lend Lease, Billion Dollar Gift, and Aid to Britain

OTD Military History

Published 27 Jun 2023Programs like Lend Lease, Mutual Aid, and the Billion Dollar Gift were support from Canada and the United States that helped Britain with war supplies and material in the darkest days of World War 2.

(more…)

August 31, 2021

Spy Affair that Started the Cold War

The Cold War

Published 3 Aug 2019Our series on the history of the Cold War period continues with a documentary on Gouzenko affair — a spy thriller that provoked the beginning of the Cold War.

Consider supporting us on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/thecoldwar

May 28, 2021

Justin Trudeau apologizes for WW2 detainment of card-carrying Fascists by Mackenzie King’s government

As Colby Cosh notes in the latest NP Platformed newsletter, it is hard to reconcile the mythological events the Prime Minister is busy apologizing for with the actual, documented facts of the case as recorded in a book published by three Italian-Canadian academics about 20 years ago:

What they found was that the 500 people, singled out from 112,000 Italian-Canadians by the government in 1940, were scarcely the victims of racial hysteria. They were, in fact, a hardcore fraction of 3,000 or so literal card-carrying Fascists in Canada. They hadn’t been thrown into camps willy-nilly, as Canada’s Japanese would be later; most had Fascist ties and sympathies that had been carefully investigated, abundantly documented and double-checked by the RCMP.

The internees had mostly been members of overtly pro-Fascist “fraternal organizations”, whose loyalty they later protested in the face of the facts. As that young reporter’s review observed, many of those groups reported directly to the Italian government, all were devoted to promoting the idea of Mussolini’s near-godhood and some helped finance Italy’s Fascist (and racist) 1935 invasion of Ethiopia, which annihilated the League of Nations security apparatus and set the table for further fascist aggression in Europe. Although the impugned Italians were detained without trial, none lost their homes or property as Japanese internees later would, and in fact none were held beyond the end of 1942.

That review was just about the only notice Enemies Within received anywhere in the Canadian press. The author, whose alliterative name you can probably guess by now, interviewed (now emeritus) Prof. Perin and was told the book had “fallen into a big black hole”. The revisionist account of Italian-Canadian internment as an out-of-control racial panic directed at anyone whose name ended in a vowel had long since taken hold in Canadian schools, and has never lost its grip.

Today, the prime minister, attentive to his nose for votes, apologized officially in the House of Commons for the “unjustified” detentions. And opposition parties are competing vigorously to out-apologize the apologizer-in-chief. One wonders what our present-day anti-fascists, who favour street beatings for anyone wearing the wrong hat, make of this laborious grieving for honest-to-God anti-Fascist action. As Michael Petrou argued courageously in the Globe and Mail on May 3, we shouldn’t be consecrating a falsehood for the sake of anyone’s political advantage. (And the CBC, to its credit, gives some attention to the historically informed side of the debate.)

November 13, 2020

QotD: Military allies

Partnership implies the burden is shared more or less equally. If I bought twenty quid’s worth of shares in The Spectator and started swanning about bitching that Conrad Black didn’t treat me as a partner, he’d rightly think I’d gone nuts. The British in their time were at least as ruthless about such realities as the Americans are today. For example, in September 1944, in one of the lesser-known conferences to prepare for the post-war world, Churchill and Roosevelt met in Quebec City. They had no compunction about excluding from their deliberations the Canadian Prime Minister, Mackenzie King, even though he was the nominal host. There’s a cartoon of the time showing King peering through a keyhole as the top dogs settled the fate of the world without him.

And guess what? Militarily speaking, Canada was a far bigger player back then than Britain is today: the Royal Canadian Navy was the world’s third-biggest surface fleet, the Canucks got the worst beach at Normandy — but hey, why bore you with details? In those days that still wasn’t enough to get you a seat at the table.

Mark Steyn, “The Brutal Cuban Winter”, The Spectator, 2002-01-26.

March 23, 2020

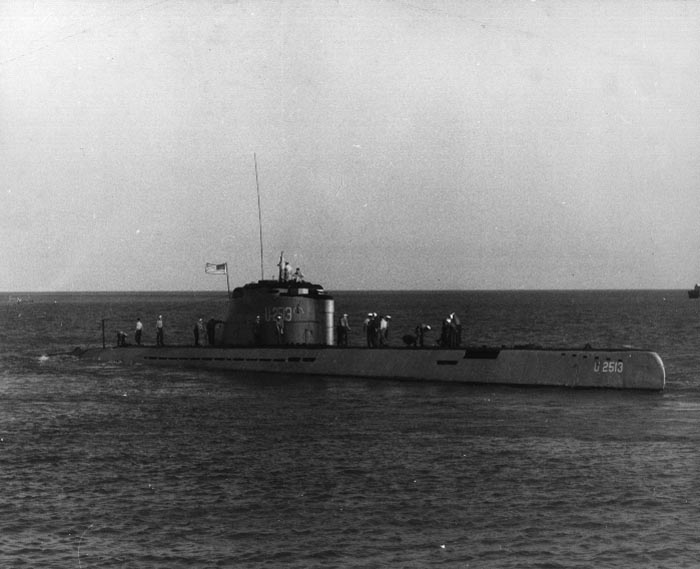

Naval strategy versus naval tactics in the Battle of the Atlantic

Ted Campbell outlines how the Battle of the Atlantic was fought between the Kriegsmarine and the Royal Navy (and the Royal Canadian Navy and, eventually, the United States Navy) in World War 2:

… there is a rather thick, and quite blurry line between naval strategy and naval tactics. One Army.ca member used the Battle of the Atlantic to distinguish between two doctrines:

- Sea control ~ which was practised by the 2nd World War allies ~ mostly British Admirals Percy Noble and Max Horton in Britain and Canadian Rear Admiral Leonard Murray in St John’s and Halifax; and

- Sea denial ~ which was practised by German Admiral Karl Dönitz.

The difference between the two tactical doctrines was very clear. The strategic aims were equally clear:

- Admiral Dönitz wanted to knock Britain out of the war ~ something that he (and Churchill) understood could be done by starving Britain into submission by preventing food, fuel and ammunition from reaching Britain from North America. (We can be eternally grateful that Adolph Hitler did not share Dönitz’ strategic vision and listened, instead, to lesser men and his own, inept, instincts); and

- Prime Minister Churchill, who really did say that “the only thing that ever really frightened me during the war was the U-boat peril“, who wanted to keep Britain fighting, at the very least resisting, until the Americans could, finally, be persuaded to come to the rescue.

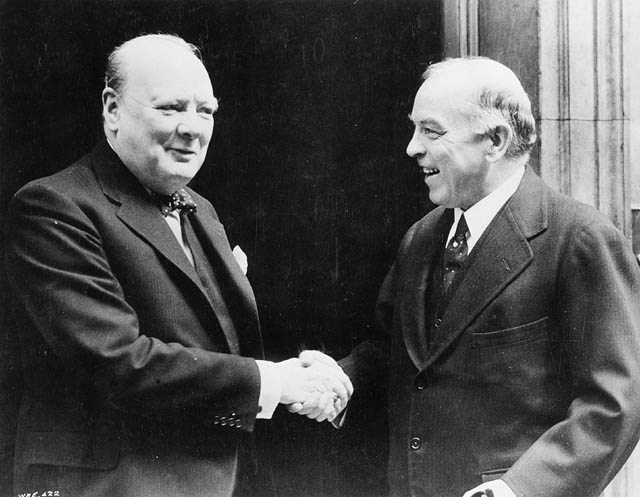

Prime Minister Winston Churchill greets Canadian PM William Lyon Mackenzie King, 1941.

Photo from Library and Archives Canada (reference number C-047565) via Wikimedia Commons.Canada’s Prime Minister Mackenzie King did have a grand strategy of his own. It was to do as much as possible while operating with the lowest possible risk of casualties ~ the conscription crisis of 1917 was, always, uppermost in his mind and he was, therefore, terrified of casualties. He mightily approved of the Navy doing a HUGE share in the Battle of the Atlantic ~ especially by building ships in Canadian yards and escorting convoys which he hoped would be a low-risk affair.

Churchill’s grand strategy was based on Britain surviving … there was, I believe, a “worst case” scenario in which the British Isles were occupied and the King and his government went to Canada or even India. But that has always seemed to me to be a sort of fantasy. The United Kingdom, without the British Isles, made no sense.

(While I believe that Rudolph Hess was, as they say, a few fries short of a happy meal, I think that he and several people in Germany believed that it might be possible to negotiate a peace with Britain which many felt was a necessary precursor to a successful campaign against Russia. The Battle of Britain (die Luftschlacht um England, September 1940 to June 1941) was, clearly, not going in Germany’s favour. Late in 1940, the Nazi high command had been forced to send a German Army formation to Libya to prevent a complete rout of the Italians. Malta still held out, meaning that Britain had air cover throughout the Mediterranean. In short, Britain was not going to go down unless it could be starved into submission ~ and in the spring of 1941, the Battle of the Atlantic was going in Germany’s favour. There was, in other words, some reason for Germans to believe that an armistice might be possible ~ freeing up all of Germany’s power to be used against the USSR.)

(But things were changing for the Allies, too. At just about the same time as Hess was flying to Scotland, then Commodore Leonard Murray of the Royal Canadian Navy, who had been in England on other duties, had met with and persuaded Admiral Sir Percy Noble, who liked Murray and had been his commander in earlier years, that a new convoy escort force should be established in Newfoundland and that it should be a largely Canadian force (with British, Dutch, Norwegian and Polish ships under command, too) and that it should be commanded by a Canadian officer. Admiral Noble insisted, to Canada, that Murray, who he liked, personally, and who had written, extensively, on convoy operations in the 1920s and ’30s, must be that commander. The establishment of the Newfoundland Escort Force, which would be more appropriately renamed the Mid Ocean Escort Force in 1942, was a key decision at the much-debated operational level of war which put an expert tactician (Murray) in command of a major force and allowed him (and Noble) to move closer to achieving Churchill’s strategic aim. The Battle of the Atlantic was not won in 1941, but it seemed to Churchill, Noble and Murray that they were a lot less likely to lose it, even without the Americans.)

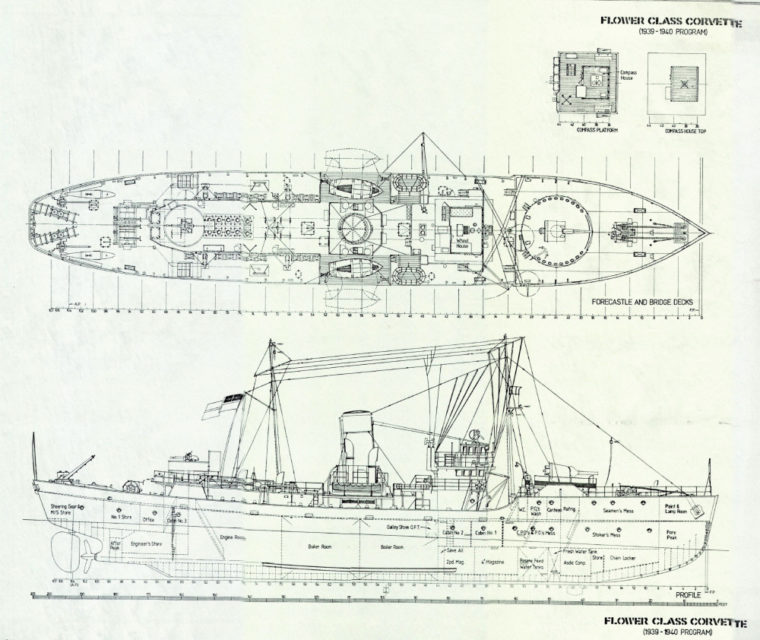

Diagram of the early Flower-class corvettes, via Lt. Mike Dunbar (https://visualfix.wordpress.com/2017/04/12/dreadful-wale-4/)

Anyway, the boundaries of strategy vs. the operational art vs. tactics were as thick and blurry in 1941 as they are today. The decision, taken in 1939, for example, to build little corvettes in the many British and Canadian yards that could not build a real warship was, in retrospect, a key strategic choice, but it was, at the time, totally materialist: just a commonsense, engineer solution to an operational problem ~ lack of ships. Ditto for the eventual decision, which had to be made by Churchill, himself, to reassign some of the big, long-range, Lancaster heavy bombers to Coastal Command. It was, once again, with the benefit of hindsight, a key strategic move, but at the time it would likely have seemed, to Capt(N) Hugues Canuel, the author of that Canadian Naval Review essay, to be materialistic, more concerned with how to use the resources available than with deciding what is needed.

I agree with Capt(N) Canuel that, by and large, Canadians have left strategic and even operational level thinking to first, the British and more recently the American admirals ~ Rear Admiral Murray being known, in the 1930s and early 1940s as a notable exception.

December 16, 2018

Mackenzie King at war

Ted Campbell remembers Canada’s Second World War Prime Minister:

Prime Minister Winston Churchill greets Canadian PM William Lyon Mackenzie King, 1941.

Photo from Library and Archives Canada (reference number C-047565) via Wikimedia Commons.

I was born in 1942, William Lyon Mackenzie King was the prime minister; my mother often said that, in the 1940s, it seemed that he would never cease to be prime minister, and she thoroughly detested him; it wasn’t all of his policies she hated, it was, mainly, how he approached the war, and a few other things ~ she was, later, fond of the Canadian poet F.R. Scott’s rather bitter epitaph:

He seemed to be in the centre because we had no centre,

No vision to pierce the smoke-screen of his politics.Truly he will be remembered wherever men honour ingenuity,

Ambiguity, inactivity, and political longevity.Let us raise up a temple to the cult of mediocrity,

Do nothing by halves which can be done by quarters.Now, Canada fought a good war, we made four absolutely vital contributions:

- We were the true “breadbasket of the empire,” our farmers fed our large Army and much of Britain’s, too;

- We were a major part of the “arsenal of democracy,” our factories and shipyards turned out all of the things, from tanks and trucks and bombers and corvettes to Bren guns and grenades that were needed to help defeat the Axis powers;

- We managed the all important British Commonwealth Air Training Plan that was a key element in the allies’ eventual success; and

- We played a huge and a significant leadership role in the Battle of the Atlantic ~ the only battle Churchill said that he really feared losing.

But under King we did each with apparent reluctance, seemingly trying to never serve any vital interest if there was even a remote chance that any political constituency might be offended ~ something that reminds me of Justin Trudeau in 2018. Our large and entirely commendable war efforts were, in the main, directed, sometimes despite King, by the indefatigable C.D. Howe, and the national unity concerns were assuaged by recruiting the universally respected Louis St Laurent.

The King era was characterized by extraordinarily tepid leadership at the top but brilliant work by strong ministers in a small cabinet. It also began Phase 1 of a national political civil war. I think that in the First World War many Canadians had either understood or had been, largely, indifferent to Quebec’s objections to conscription. But in the 1940s we had better mass communications and many Canadians were less understanding of Quebec’s reluctance to participate in that war, especially as Canadian casualties mounted after Hong Kong and then in Italy and then in France, Belgium and Holland. Louis St Laurent did not try to explain French Quebec’s misgivings to English Canada, his job was to maintain, by force of his own stellar reputation and personality, just enough support in Quebec and, as he easily did, to “outclass” the vocal, crypto-fascist, French Canadian opponents to the war. But there was another division fomenting inside the Liberal Party of Canada: both Howe and St Laurent had a new vision for Canada in the post war world; both saw Canada as an important actor on the world stage; both were frustrated by King’s timid leadership; it is very probable that had St Laurent, the foreign minister, rather than King, [been] the prime minister, led Canada’s delegation to the UN’s founding conference in San Francisco in June of 1945 that Canada, not France, would have been the fifth member of the Security Council (or that it would have had only four members. as originally planned). St Laurent, especially, was known, liked and respected in both London and Washington; both he and Howe were highly regarded as leaders and as statesmen … King was not; Churchill distrusted him because he has actively supported Chamberlain’s appeasement policy and it seems to me that both Churchill and Roosevelt saw him as little more than an errand boy.

April 27, 2017

QotD: Canada the (self-imagined) “moral superpower” … the military midget

… Canada has no influence whatever in the world. It is unique in this condition among G7 countries, because it has a monstrously inadequate defence capability and takes no serious initiatives in the Western alliance or in international organizations.

Canadians seem to imagine that influence can be had in distant corners of the world just by being virtuous and altruistic and disinterested. That is not how international relations work. The powers that have the money and the applicable military strength have the influence, although those elements may be reinforced if a country or its leader is able to espouse a noble or popular cause with great persuasiveness. This last was the case in the Second World War, where Winston Churchill, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Charles de Gaulle and Adolf Hitler were all, in their different ways, inspiring public speakers who could whip up the enthusiasm of their peoples. Churchill and Roosevelt stirred the masses of the whole world who loved and sought freedom. There are no world leaders now with any appreciable ability to stir world opinion, and influence in different theatres is measured exclusively in military and economic strength, unless there is a colossal moral imbalance between contending parties. Even where such a moral imbalance exists, as in the contest between civilized and terrorism-supporting countries, the advantage is not easily asserted.

[…]

But we are almost entirely dependent on the United States for our own defence. When President Roosevelt said at Queen’s University in Kingston in 1938 that the U.S. would protect Canada from foreign invasion, Mackenzie King accepted the responsibility of assuring that invaders could not reach the U.S. through Canada. Since the Mulroney era, we have just been freeloaders. If we want to be taken seriously, we have to make a difference in the Western alliance, which the Trump administration has set out to revitalize. As I have written here before, a defence build-up: high-tech, increased numbers, and adult education, is a win-double, an added cubit to our national stature influence (and pride), and the best possible form of public-sector economic stimulus. It is frustrating that successive governments of both major parties have not seen these obvious truths. Strength, not amiable piety, creates national influence.

Conrad Black, “Being nice gets Canada liked. But we won’t be respected until we pull our weight”, National Post, 2017-04-14.