Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 26 Nov 2024Game hens roasted with a hazelnut and herb sauce

City/Region: Rome | Macedonia

Time Period: 1st CenturyThrowing lavish feasts was one foreign custom that Alexander the Great was all too happy to adopt. We don’t have any recipes from Alexander’s court, so I looked to the ancient Roman cookbook, De re coquinaria, to find a recipe that used ingredients that Alexander would have had.

The herbs and seasonings in the sauce combine to form a new complex flavor that is delicious. The hazelnuts are prominent and form a wonderful crust on the game hens, and the garum adds its distinctive savory umami note. You can either make the sauce and serve it forth with poultry that you’ve already cooked, or roast the birds with the sauce like I did.

Aliter Ius in Avibus, Another Sauce for Birds:

Pepper, parsley, lovage, dried mint, safflower, pour in wine, add toasted hazelnuts or almonds, a little honey with wine and vinegar, season with garum. Add oil to this in a pot, heat it, stir in green celery and calamint. Make incisions in the birds and pour the sauce over them.

— Apicius de re coquinaria, 1st century

April 8, 2025

What did Alexander the Great eat?

March 1, 2025

QotD: Roman Republic versus Seleucid Empire – the Battle of Magnesia

Rome’s successes at sea in turn set conditions for the Roman invasion of Anatolia, which will lead to the decisive battle at Magnesia, but of course in the midst of our naval narrative, we rolled over into a new year, which means new consuls. The Senate extended Glabrio’s command in Greece to finish the war with the Aetolians, but the war against Antiochus was assigned to Lucius Cornelius Scipio, one of the year’s consuls and brother of Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus, the victor over Hannibal at Zama (202). There’s an exciting bit of politics behind Scipio getting the assignment (including his famous brother promising to serve as one of his military tribunes), but in a sense that’s neither here nor there. As we’ve seen, Rome has no shortage of capable generals. From here on, if I say “Scipio”, I mean Lucius Cornelius Scipio; if I want his brother, I’ll say “Scipio Africanus”.

Scipio also brought fresh troops with him. The Senate authorized him to raise a supplementum (recruitment to fill out an army) of 3,000 Roman infantry, 100 Roman cavalry, 5,000 socii infantry and 200 socii cavalry (Livy 37.2.1) as well as authorizing him to carry the war into Asia (meaning Anatolia or Asia Minor) if he thought it wise – which of course he will. In addition to this, the two Scipios also called for volunteers from Scipio Africanus’ veterans and got 5,000 of them, a mix of Romans and socii (Livy 37.4.3), so all told Lucius Cornelius Scipio is crossing to Greece with reinforcements of some 13,000 infantry (including some battle-hardened veterans), 300 cavalry and one Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus.1 That said, a significant portion of this force is going to end up left in Greece to handle garrison duty and the Aetolians. Antiochus III, for his part, spends this time raising forces for a major battle, while dispatching his son Seleucus (the future Seleucus IV, r. 187-175) to try to raid Pergamum, Rome’s key ally in the region.

Once the Romans arrive (and join up with Eumenes’ army), both sides maneuvered to try and get a battle on favorable terms. Antiochus III’s army was massive with lots of cavalry – 62,000 infantry and 12,000 cavalry, an army on the same general order of magnitude as the one that fought at Raphia – so he sought an open area, setting up his fortified camp near Magnesia, with fairly formidable defenses – a ditch with a double-rampart (Livy 37.37.9-11). Unsurprisingly, the Romans, with a significant, but smaller force, preferred a fight in more confined quarters and for several days the armies sat opposite each other with minor skirmishes (Livy 37.38).

The problem Scipio faced was a simple one: the year was coming to a close, which meant that soon new consuls would be elected and he could hardly count on his command being extended. Consequently, Scipio calls together his war council – what the Romans call a consilium – to ask what he should do if Antiochus III couldn’t be lured into battle on favorable terms. The answer he got back was to force a battle and so force a battle Scipio did, advancing forward onto the ground of Antiochus’ choosing, leading to the Battle of Magnesia.

We have two accounts of this battle which mostly match up, one in Livy (Livy 37.39-44) and another in Appian’s Syrian Wars (App. Syr. 30-36). Livy here is generally the better source and chances are both authors are relying substantially on Polybius (who would be an even better source), whose account of the battle is lost.

Antiochus III’s army was enormous, with a substantial superiority in cavalry. From left to right, according to Livy (Livy 37.40), Antiochus III deployed: Cyrtian slinger and Elymaean archers (4,000), then a unit of caetrati (4,000; probably light infantry peltasts), then the contingent of Tralli (1,500; light infantry auxiliaries from Anatolia), then Carian and Cilicians equipped like Cretans (1,500; light archer infantry), then the Neo-Cretans (1,000; light archer infantry), then the Galatian cavalry (2,500; mailed shock cavalry), then a unit of Tarantine cavalry (number unclear, probably 500; Greek light cavalry), a part of the “royal squadron” of cavalry (1,000; Macedonian shock cavalry), then the ultra-heavy cataphract cavalry (3,000), supported by a mixed component of auxiliaries (2,700; medium thureophoroi infantry?) along with his scythed chariots and Arab camel troops.

That gets us to the central component of the line (still reading left to right): Cappadocians (2,000) who Livy notes were similarly armed to the Galatian infantry (1,500, unarmored, La Tène infantry kit, so “mediums”) who come next. Then the main force of the phalanx, 16,000 strong with 22 elephants. The phalanx was formed 32 ranks deep, with the intervals between the regiments covered by the elephants deployed in pairs, creating an articulated or enallax phalanx like Pyrrhus had, but using elephants rather than infantry to cover the “hinges”. This may in fact, rather than being a single phalanx 32 men deep be a “double” phalanx (one deployed behind the other) like we saw at Sellasia. Then on the right of the phalanx was another force of 1,500 Galatian infantry. Oddly missing here is the main contingent of the elite Silver Shields (the Argyraspides); some scholars2 note that a contingent of them 10,000 strong would make Livy’s total strength numbers and component numbers match up and he has just forgotten them in the main line. We might expect them to be deployed to the right of the main phalanx (where Livy will put the infantry Royal Cohort (regia cohors), confusing a subunit of the argyraspides with the larger whole unit. Michael Taylor in a forthcoming work3 has suggested they may also have been deployed behind the cavalry we’re about to get to or otherwise to their right.

That gets us now to the right wing (still moving left to right; you begin to realize how damn big this army is), we have more cataphracts (3,000, armored shock cavalry), the elite cavalry agema (1,000; elite Mede/Persian cavalry, probably shock), then Dahae horse archers (1,200; Steppe horse archers), then Cretan and Trallian light infantry (3,000), then some Mysian Archers (2,500) and finally another contingent of Cyrtian slinger and Elymaean archers (4,000).

This is, obviously, a really big army. But notice that a lot of its strength is in light infantry: combining the various archers, slingers and general light infantry (excluding troops we suspect to be “mediums”) we come to something like 21,500 lights, plus another 7,700 “medium” infantry and then 26,000 heavy infantry (accounting for the missing argyraspides). That’s 55,200 total, but Livy reports a total strength for the army of 62,000; it’s possible the missing remainder were troops kept back to defend the camp, in which case they too are likely light infantry. A Roman army’s infantry contingent is around 28% “lights” (the velites), who do not occupy any space in the main battle line. Antiochus’ infantry contingent, while massive, is 39% “lights” (and another 14% “mediums”), some of which do seem to occupy actual space in the battle line.

Of course Antiochus also has a massive amount of cavalry ranging from ultra-heavy cataphracts to light but highly skilled horse archers and massive cavalry superiority covereth a multitude of sins.

But the second problem with this gigantic army is one that – again, in a forthcoming work – Michael Taylor has pointed out. The physical space of the battlefield at Magnesia is not big enough to deploy the whole thing […]

Now Livy specifies that the flanks of Antiochus’ army curve forward, describing them as “horns” (cornu) rather than “wings” (alae) and noting they were “a little bit advanced” (paulum producto), which may be an effort to get more of this massive army actually into the fight […]. So while this army is large, it’s also unwieldy and difficult to bring properly into action and it’s not at all clear from either Livy or Appian that the whole army actually engaged – substantial portions of that gigantic mass of light infantry on the wings just seem to dissolve away once the battle begins, perhaps never getting into the fight in the first place.

The Roman force was deployed in its typical formation, with the three lines of the triplex acies and the socii flanking the legions (Livy 37.39.7-8), with the combined Roman and socii force being roughly 20,000 strong (the legions and alae being somewhat over-strength). In addition Eumenes, King of Pergamum was present and the Romans put his force on their right to cover the open flank, while he anchored his left flank on the Phrygios River. Eumenes’ wing consisted of 3,000 Achaeans (of the Achaean League) that Livy describes as caetrati and Appian describes as peltasts (so, lights), plus nearly all of Scipio’s cavalry: Eumenes’ cavalry guard of 800, plus another 2,200 Roman and socii cavalry, and than some auxiliary Cretan and Trallian light infantry, 500 each. Thinking his left wing, anchored on the river, relatively safe, Scipio posted only four turmae of cavalry there (120 cavalry). He also had a force of Macedonians and Thracians mixed together – so these are probably “medium” infantry – who had come as volunteers, who he posts to guard the camp rather than in the main battleline. I always find this striking, because I think a Hellenistic army would have put these guys in the front line, but a Roman commander looks at them and thinks “camp guards”. The Romans also had some war elephants, sixteen of them, but Scipio assesses that North African elephants won’t stand up to the larger Indian elephants of the Seleucids (which is true, they won’t) and so he puts them in reserve behind his lines rather than out front where they’d just be driven back into him. All told then, the Roman force is around 26,000 infantry and 3,000 cavalry – badly outnumbered by Antiochus, but of a relatively higher average quality and a bit more capable of actually fitting its entire combat power into the space.

The Battle

Because the armies are so large, much like as happened at Raphia, the battle that results is almost three battles running in parallel: the two wings and the center. Antiochus III commanded from his right wing, where – contrary to the expectations of Scipio who thought the river would secure his flank there – he intended his main attack. His son Seleucus commanded the left. Livy reports a light rain which interfered with both with visibility and some of Antiochus’ light troops’ weapons, as their bows and slings reacted poorly to the moisture (as composite bows will sometimes do; Livy 37.41.3-4, note also App. Syr. 33).Antiochus opens the battle on his left with his scythed chariots, a novel “gimmick” weapon (heavy chariots with blades all over them, used to shock infantry out of position). This may have been a nasty surprise for the Romans, but given the dispositions of the army, it was Eumenes, not Scipio who faces the chariots and as Livy notes, Eumenes was well aware how to fight them (Livy 37.41.9), using his light troops – those Cretan archers and Trallian javelin-troops. Deployed in loose order, they were able to move aside to avoid the chariots better than heavy infantry in close-order (similar tactics are used against elephants) and could with their missiles strike at chariot drivers and horses at range (Livy 37.41.10-12). Turning back this initial attack seems to have badly undermined the morale of the Seleucid left-wing, parts of which fled, creating a gap between the extreme left-wing and the heavy cavalry contingent. Eumenes then, with the Roman cavalry, promptly hammered the disordered line, hitting first the camel troops, then in the confusion quickly overwhelming the rest of the cavalry, including the cataphracts, leading Antiochus’ left wing to almost totally collapse, isolating the phalanx in the center. It’s not clear what the large mass of light infantry on the extreme edge of the battlefield was doing.

Meanwhile on the other side of the battle, where Scipio had figured a light screen of 120 equites would be enough to hold the end of the line, Antiochus delivered is cavalry hammer-blow successfully. Obnoxiously, both of our sources are a lot less interested in describing how he does this (Livy 37.42.7-8 and App. Syr. 34), which is frustrating because it is a bit hard to make sense of how it turns out. On the one hand, the constricted battlefield will have meant that, regardless of how they were positioned, those argyraspides are going to end up following Antiochus’ big cavalry hammer on the (Seleucid) right. They then overwhelm the cavalry and put them to flight and then push the infantry of that wing (left ala of socii and evidently a good portion of the legion next to it) back to the Roman camp.

On the other hand, the Roman infantry line reaches its camp apparently in good order or something close to it. Marcus Aemilius, the tribune put in charge of the camp is able to rush out, reconstitute the infantry force and, along with the camp-guard, halt Antiochus’ advance. The thing is, infantry when broken by cavalry usually cannot reform like that, but the distance covered, while relatively short, also seems a bit too long for the standard legionary hastati-to-principes-to-triarii retrograde. Our sources (also including a passage of Justin, a much later source, 31.8.6) vary on exactly how precipitous the flight was and it is possible that it proceeded differently at different points, with some maniples collapsing and others making an orderly retrograde. In any case, it’s clear that the Roman left wing stabilized itself outside of the Roman camp, much to Antiochus’ dismay. Eumenes, having at this point realized both that he was winning on his flank and that the other flank was in trouble dispatched his brother Attalus with 200 cavalry to go aid the ailing Roman left wing; the arrival of these fellows seem to have caused panic and Antiochus at this point begins retreating.

Meanwhile, of course, there is the heavy infantry engagement at the center. Pressured and without flanking support, Appian reports that the Seleucid phalanx first admitted what light infantry remained and then formed square, presenting their pikes tetragonos, “on all four sides” (App. Syr. 35), a formation known as a plinthion in some Greek tactical manuals. Forming this way under pressure on a chaotic battlefield is frankly impressive (though if they were formed as a double-phalanx rather than a double-thick single-phalanx, that would have made it easier) and a reminder that the core of Antiochus’ army was quite capable. Unable in this formation to charge, the phalanx was showered with Roman pila and skirmished by Eumenes’ lighter cavalry; the Romans seem to have disposed of Antiochus’ elephants with relative ease – the Punic Wars had left the Romans very experienced at dealing with elephants (Livy 37.42.4-5). Appian notes that some of the elephants, driven back by the legion and maddened disrupted the Seleucid square, at which point the phalanx at last collapsed (App. Syr. 35); Livy has the collapse happen much faster, but Appian’s narrative here seems more plausible.

What was left of Antiochus’ army now fled to their camp – not far off, just like the Roman one – leading to a sharp battle at the camp which Livy describes as ingens et maior prope quam in acie cades, “a huge slaughter, almost greater than that in the battle” (Livy 37.43.10), with stiff resistance at the camp’s gates and walls holding up the Romans before they eventually broke through and butchered the survivors. Livy reports that of Antiochus’ forces, 50,000 infantry and 3,000 cavalry were killed, another 1,500 captured; these seem really high as figures go, but Appian reports almost the exact same. Interesting, Livy doesn’t report the figure in his own right or attribute it to Polybius but instead simply notes “it is said that”, suggesting he may not be fully confident of the number either. Taylor supposes, reasonably I think, that this oversized figure may also count men who fled from the battlefield, reflecting instead that once Antiochus III could actually reconstitute his army, he had about 19,000 men, most of the rest having fled.4 Either way, the resulting peace makes clear that the Seleucid army was shattered beyond immediate repair.

Roman losses, by contrast, were shockingly light. Livy reports 300 infantry lost, 24 Roman cavalry and 25 out of Eumenes’ force; Appian adds that the 300 infantry were “from the city” – meaning Roman citizens – so some socii casualties have evidently been left out (but he trims Eumenes’ losses down to just fifteen cavalry) (Livy 37.44.2-3; App. Syr. 36). Livy in addition notes that many Romans were wounded in addition to the 300 killed. This is an odd quirk of Livy’s casualty reports for Roman armies against Hellenistic armies and I suspect it reflects the relatively high effectiveness of Roman body armor, by this point increasingly dominated by the mail lorica hamata: good armor converts lethal blows into survivable wounds.5 It also fits into a broader pattern we’ve seen: Hellenistic armies that face Roman armies always take heavy casualties, winning or losing, but when Roman armies win they tend to win lopsidedly. It is a trend that will continue.

So why Roman victory at Magnesia? It is certainly not the case that the Romans had the advantage of rough terrain in the battle: the battlefield here is flat and fairly open. It should have been ideal terrain for a Hellenistic army.

A good deal of the credit has to go to Eumenes, which makes the battle a bit hard to extrapolate from. It certainly seems like Eumenes’ quick thinking to disperse the Seleucid chariots and then immediately follow up with his own charge was decisive on his flank, though not quite battle winning. Eumenes’ forces, after all, lacked the punch to disperse the heavier phalanx, which did not panic when its wing collapsed. Instead, the Seleucid phalanx, pinned into a stationary, defensive position by Eumenes’ encircling cavalry, appears to have been disassembled primary by the Roman heavy infantry, peppering it with pila before inducing panic into the elephants. It turns out that Samnites make better “glue” for an articulated phalanx than elephants, because they are less likely to panic.

Meanwhile on the Seleucid right (the Roman left), the flexible and modular nature of the legion seems to have been a major factor. Antiochus clearly broke through the Roman line at points, but with the Roman legion’s plethora of officers (centurions, military tribunes, praefecti) and with each maniple having its own set of standards to rally around, it seems like the legion and its socii ala managed to hold together and eventually drive Antiochus off, despite being pressured. That, in and of itself, is impressive: it is the thing the Seleucid center fails to do, after all.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Phalanx’s Twilight, Legion’s Triumph, Part IVb: Antiochus III”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2024-04-05.

1. I enjoy this joke because the idea of bringing Scipio Africanus along as a junior officer is amusing, but I should note that in the event, he doesn’t seem to have had much of a role in the campaign.

2. E.g. Bar Kockva, The Seleucid Army: Organization and Tactics in the Great Campaigns (1979)

3. “A Commander Will Put an End to his Insolence: the Battle of Magnesia, 190BC” to appear in The Seleucids at War: Recruitment, Organization and Battles (forthcoming in 2024), eds. Altay Coşkun and Benhamin E. Scolnic.

4. Taylor, Antiochus the Great (2013), 143.

5. On this, see, uh, me, “The Adoption and Impact of Roman Mail Armor in the Third and Second Centuries B.C.” Chiron 52 (2022).

February 23, 2025

QotD: The Hellenistic army system as a whole

I should note here at the outset that we’re not going to be quite done with the system here – when we start looking at the third and second century battle record, we’re going to come back to the system to look at some innovations we see in that period (particularly the deployment of an enallax or “articulated” phalanx). But we should see the normal function of the components first.

No battle is a perfect “model” battle, but the Battle of Raphia (217BC) is handy for this because we have the two most powerful Hellenistic states (the Ptolemies and Seleucids) both bringing their A-game with very large field armies and deploying in a fairly standard pattern. That said, there are some quirks to note immediately: Raphia is our only really good order of battle of the Ptolemies, but as our sources note there is an oddity here, specifically the mass deployment of Egyptians in the phalanx. As I noted last time, there had always been some ethnic Egyptians (legal “Persians”) in the phalanx, but the scale here is new. In addition, as we’ll see, the position of Ptolemy IV himself is odd, on the left wing matched directly against Antiochus III, rather than on his own right wing as would have been normal. But this is mostly a fairly normal setup and Polybius gives us a passably good description (better for Ptolemy than Antiochus, much like the battle itself).

We can start with the Seleucid Army and the tactical intent of the layout is immediately understandable. Antiochus III is modestly outnumbered – he is, after all, operating far from home at the southern end of the Levant (Raphia is modern-day Rafah at the southern end of Gaza), and so is more limited in the force he can bring. His best bet is to make his cavalry and elephant superiority count and that means a victory on one of the wings – the right wing being the standard choice. So Antiochus stacks up a 4,000 heavy cavalry hammer on his flank behind 60 elephants – Polybius doesn’t break down which cavalry, but we can assume that the 2,000 with Antiochus on the extreme right flank are probably the cavalry agema and the Companions, deployed around the king, supported by another 2,000 probably Macedonian heavy cavalry. He then uses his Greek mercenary infantry (probably thureophoroi or perhaps some are thorakitai) to connect that force to the phalanx, supported by his best light skirmish infantry: Cretans and a mix of tough hill folks from Cilicia and Caramania (S. Central Iran) and the Dahae (a steppe people from around the Caspian Sea).

His left wing, in turn, seems to be much lighter and mostly Iranian in character apart from the large detachment of Arab auxiliaries, with 2,000 more cavalry (perhaps lighter Persian-style cavalry?) holding the flank. This is a clearly weaker force, intended to stall on its wing while Antiochus wins to the battle on the right. And of course in the middle [is] the Seleucid phalanx, which was quite capable, but here is badly outnumbered both because of how full-out Ptolemy IV has gone in recruiting for his “Macedonian” phalanx and also because of the massive infusion of Egyptians.

But note the theory of victory Antiochus III has: he is going to initiate the battle on his right, while not advancing his left at all (so as to give them an easier time stalling), and hope to win decisively on the right before his left comes under strain. This is, at most, a modest alteration of Alexander-Battle.

Meanwhile, Ptolemy IV seems to have anticipated exactly this plan and is trying to counter it. He’s stacked his left rather than his right with his best troops, including his elite infantry (the agema and peltasts, who, while lighter, are more elite) and his best cavalry, supported by his best (and only) light infantry, the Cretans.1 Interestingly, Polybius notes that Echecrates, Ptolemy’s right-wing commander waits to see the outcome of the fight on the far side of the army (Polyb. 6.85.1) which I find odd and suggests to me Ptolemy still carried some hope of actually winning on the left (which was not to be). In any case, Echecrates, realizing that sure isn’t happening, assaults the Seleucid left.

I think the theory of victory for Ptolemy is somewhat unconventional: hold back Antiochus’ decisive initial cavalry attack and then win by dint of having more and heavier infantry. Indeed, once things on the Ptolemaic right wing go bad, Ptolemy moves to the center and pushes his phalanx forward to salvage the battle, and doing that in the chaos of battle suggests to me he always thought that the matter might be decided that way.

In the event, for those unfamiliar with the battle: Antiochus III’s right wing crumples the Ptolemaic left wing, but then begins pursuing them off of the battlefield (a mistake he will repeat at Magnesia in 190). On the other side, the Gauls and Thracians occupy the front face of the Seleucid force while the Greek and Mercenary cavalry get around the side of the Seleucid cavalry there and then the Seleucid left begins rolling up, with the Greek mercenary infantry hitting the Arab and Persian formations and beating them back. Finally, Ptolemy, having escaped the catastrophe on his left wing, shows up in the center and drives his phalanx forward, where it wins for what seem like obvious reasons against an isolated Seleucid phalanx it outnumbers almost 2-to-1.

But there are a few structural features I want to note here. First, flanking this army is really hard. On the one hand, these armies are massive and so simply getting around the side of them is going to be difficult (if they’re not anchored on rivers, mountains or other barriers, as they often are). Unlike a Total War game, the edge of the army isn’t a short 15-second gallop from the center, but likely to be something like a mile (or more!) away. Moreover, you have a lot of troops covering the flanks of the main phalanx. That results, in this case, in a situation where despite both wings having decisive actions, the two phalanxes seem to be largely intact when they finally meet (note that it isn’t necessarily that they’re slow; they seem to have been kept on “stand by” until Ptolemy shows up in the center and orders a charge). If your plan is to flank this army, you need to pick a flank and stack a ton of extra combat power there, and then find a way to hold the center long enough for it to matter.

Second, this army is actually quite resistive to Alexander-Battle: if you tried to run the Issus or Gaugamela playbook on one of these armies, you’d probably lose. Sure, placing Alexander’s Companion Cavalry between the Ptolemaic thureophoroi and Gallic mercenaries (about where he’d normally go) would have him slam into the Persian and Medean light infantry and probably break through. But that would be happening at the same time as Antiochus’ massive 4,000-horse, 60-elephant hammer demolished Ptolemaic-Alexander’s left flank and moments before the 2,000 cavalry left-wing struck Alexander himself in his flank as he advanced. The Ptolemaic army is actually an even worse problem, because its infantry wings are heavier, making that key initial cavalry breakthrough harder to achieve. Those chunky heavy-cavalry wings ensure that an effort to break through at the juncture of the center and the wing is foolhardy precisely because it leaves the breakthrough force with heavy cavalry to one side and heavy infantry to the other.

I know this is going to cause howls of pain and confusion, but I do not think Alexander could have reliably beaten either army deployed at Raphia; with a bit of luck, perhaps, but on the regular? No. Not only because he’d be badly outnumbered (Alexander’s army at Gaugamela is only 40,000 infantry and 7,000 cavalry) but because these armies were adapted to precisely the sort of army he’d have and the tactics he’d use. Even without the elephants (and elephants gave Alexander a hell of a time at the Hydaspes), these armies can match Alexander’s heavy infantry core punch-for-punch while having enough force to smash at least one of his flanks, probably quite quickly. Note that the Seleucid Army – the smaller one at Raphia – has almost exactly as much heavy infantry at Raphia as Alexander at Gaugamela (30,000 to 31,000), and close to as much cavalry (6,000 to 7,000), but of course also has a hundred and two elephants, another 5,000 more “medium” infantry and massive superiority in light infantry (27,000 to 9,000). Darius III may have had no good answer to the Macedonian phalanx, but Antiochus III has a Macedonian phalanx and then essentially an entire second Persian-style army besides (and his army at Magnesia is actually more powerful than his army at Raphia).

This is not a degraded form of Alexander’s army, but a pretty fearsome creature of its own, which supplements an Alexander-style core with larger amounts of light and medium troops (and elephants), without sacrificing much, if any, in terms of heavy infantry and cavalry. The tactics are modest adjustments to Alexander-Battle which adapt the military system for symmetrical engagements against peer armies. The Hellenistic Army is a hard nut to crack, which is why the kingdoms that used them were so successful during the third century, to the point that, until the Romans show up, just about the only thing which could beat a Hellenistic army was another Hellenistic army.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Phalanx’s Twilight, Legion’s Triumph, Part Ib: Subjects of the Successors”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2024-01-26.

1. You can tell how much those Cretans are valued, given that they get placed in key positions in both armies.

February 17, 2025

QotD: Decisive factors in the Roman victory over the Seleucids

Zooming out even further, why Roman victory in the Roman-Seleucid War? I think there are a few clear factors here.

Ironically for a post covering land battles, the most important factor may be naval: Rome’s superior naval resources (and better naval allies), which gave the Romans an enormous operational advantage against Antiochus. In the initial phase, the Romans could get more troops to Greece than the king could, while further on, Roman naval supremacy allowed Roman armies to operate in Anatolia in force (while Antiochus, even had he won in Greece, had no hope of operating in Italy). Neutralizing Antiochus’ navy both opened up options for the Romans and closed down options for Antiochus, setting the conditions for Roman victory. It would have also neutered any Roman defeat. If Antiochus wins at Magnesia, he cannot then immediately go on the offensive, after all: he has merely bought perhaps a year or two of time to rebuild his navy and try to contest the Aegean again. Given the astounding naval mobilizations Rome had shown itself capable of in the third century, one cannot imagine Antiochus was likely to win that contest.

Meanwhile, the Romans had better allies, in part as a consequence of the Romans being better at getting allies. The Romans benefit substantially from allied Achaean, Pergamese and Rhodian ships and troops, as well as support from the now-humbled Philip V of Macedon and even supplies and auxiliaries from Numidia and Carthage. Alliance-management is a fairly consistent Roman strength and it shows here. It certainly seems to help that Roman protestations that they had little interest in a permanent presence in Greece seem to have been somewhat true; Rome won’t set up a permanent provincia in Macedonia until 146 (though the Romans do expect their influence to predominate before then). By contrast, Antiochus III, clearly bent on rebuilding Alexander’s empire, was a more obvious threat to the long-term independence and autonomy of Greek states like the Pergamum or Rhodes.

Finally, there is the remarkable Seleucid glass jaw. The Romans, after all, sustained a defeat very much like Magnesia against Hannibal in 216 (the Battle of Cannae) and kept fighting. By contrast, Antiochus is forced into a humiliating peace after Magnesia, in which he cedes all of Anatolia, gives up any kind of navy and is forced to pay a crippling financial indemnity which will fatally undermine the reign of his successor and son Seleucus IV (leading to his assassination in 175, leading to yet further Seleucid weakness). Part of this glass jaw may have been political: after Magnesia, Antiochus’ own aristocrats seem pretty well done with their king’s adventurism against Rome.

But at the same time, some of it was clearly military. Antiochus didn’t have a second army to fall back on and Magnesia represented essentially a peak “all-call” Seleucid mobilization. A similar defeat at Raphia had forced a similarly unfavorable peace earlier in his reign, after all. Part of the problem, I would argue, is that the Seleucids needed their army for more than just war: they needed it to enforce taxation and tribute on their own recalcitrant subjects. As a result, no Seleucid king could afford to “go for broke” the way the Roman Republic could, nor could the Seleucids ever fully mobilize the massive population of their realm. The very nature of the Hellenistic kingdom’s ethnic hierarchy made fully tapping the potential resources of the kingdom impossible.

As a result, while Antiochus III was not an incompetent general, he ruled a deceptively weak giant. Massive revenues were offset by equally massive security obligations and the Seleucids seem to have been perenially cash strapped (with a nasty habit of looting temples to make up for it). The very nature of the Seleucid Empire – like the Ptolemaic one – as an ethnic empire where Macedonians ruled and non-Macedonians were ruled kept Antiochus from being able to fully mobilize his subjects. It may also explain why so many of those light infantry auxiliaries seem to have run off without much of a fight. Eumenes and his Pergamese troops fought for their independence, the Romans for the greater glory of Rome and the socii for their own status and loot within the Roman system, but what could Antiochus offer a subjected Carian or Cilician except a paycheck and a future of continued subjugation? That’s not much to die for.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Phalanx’s Twilight, Legion’s Triumph, Part IVb: Antiochus III”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2024-04-05.

February 10, 2025

QotD: The Roman Republic versus the heirs of Alexander the Great

Last time, we finished our look at the third-century successes of the phalanx with the career of Pyrrhus of Epirus, concluding that even when handled very well with a very capable body of troops, Hellenistic armies struggled to achieve the kind of decisive victories they needed against the Romans to achieve strategic objectives. Instead, Pyrrhus was able to achieve a set of indecisive victories (and a draw), which was simply not anywhere close to enough in view of the tremendous strategic depth of Rome.

Well, I hope you got your fill of Hellenistic armies winning battles because it is all downhill from here (even when we’re fighting uphill). For the first half of the second century, from 200 to 168, the Romans achieve an astounding series of lopsided victories against both (Antigonid) Macedonian and Seleucid Hellenistic armies, while simultaneously reducing several other major players (Pergamon, Egypt) to client states. And unlike Pyrrhus, the Romans are in a position to “convert” on each victory, successfully achieving their strategic objectives. It was this string of victories, so shocking in the Greek world, that prompted Polybius to write his own history, covering the period from 264 to 146 to try to explain what the heck happened (much of that history is lost, but Polybius opens by suggesting that anyone paying attention to the First Punic War (264-241) ought to have seen this coming).

That said, this series of victories is complex. Of the five major engagements (The River Aous, Cynoscephalae, Thermopylae, Magnesia, and Pydna) Rome commandingly wins all of them, but each battle is strange in its own way. So we’re going to look at each battle and also take a chance to lay out a bit of the broader campaigns, asking at each stage why does Rome win here? Both in the tactical sense (why do they win the battle) and also in the strategic sense (why do they win the war).

We’re going to start with the war that brought Rome truly into the political battle royale of the Eastern Mediterranean, the Second Macedonian War (200-196). Rome was acting, in essence, as an interloper in long-running conflicts between the various successor dynasties of Alexander the Great as well as smaller Greek states caught in the middle of these larger brawling empires. Briefly, the major players are the Ptolemaic Dynasty, in Egypt (the richest state), the Seleucid Dynasty out of Syria and Mesopotamia (the largest state) and the Antigonid Kingdom in Macedonia (the smallest and weakest state, but punching above its weight with the best man-for-man army). The minor but significant players are the Attalid dynasty in Pergamon, a mid-sized Hellenistic power trapped between the ambitions of the big players, two broad alliances of Greek poleis in the Greek mainland the Aetolian and Achaean Leagues, and finally a few freewheeling poleis, notably Athens and Rhodes. The large states are trying to dominate the system, the small states trying to retain their independence and everyone is about to get rolled by the Romans.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Phalanx’s Twilight, Legion’s Triumph, Part IVa: Philip V”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2024-03-15.

November 29, 2024

Greek History and Civilization, Part 8 – The Hellenistic Age

seangabb

Published Jul 17, 2024This eighth lecture in the course covers the Hellenistic Age of Greece — from the death of Alexander in 323 BC to about the death of Cleopatra in 30 BC.

(more…)

September 29, 2024

QotD: Pyrrhus, King of Epirus

Last time, we sought to assess some of the assumed weaknesses of the Hellenistic phalanx in facing rough terrain and horse archer-centered armies and concluded, fundamentally, that the Hellenistic military system was one that fundamentally worked in a wide variety of environments and against a wide range of opponents.

This week, we’re going to look at Rome’s first experience of that military system, delivered at the hands of Pyrrhus, King of Epirus (r. 297-272). The Pyrrhic Wars (280-275) are always a sticking point in these discussions, because they fit so incongruously with the rest. From 214 to 148, Rome will fight four “Macedonian Wars” and one “Syrian War” and utterly demolish every major Hellenistic army it encounters, winning every single major pitched battle and most of them profoundly lopsidedly. Yet Pyrrhus, fighting the Romans some 65 years earlier manages to defeat Roman armies twice and fight a third to a messy draw, a remarkably better battle record than any other Hellenistic monarch will come anywhere close to achieving. At the same time, Pyrrhus, quite famously, fails to get anywhere with his victories, taking losses he can ill-afford each time (thus the notion of a “Pyrrhic victory”), while the Roman armies he fights are never entirely destroyed either.

So we’re going to take a more in-depth look at the Pyrrhic Wars, going year-by-year through the campaigns and the three major battles at Heraclea (280), Ausculum (279) and Beneventum (275) and try to see both how Pyrrhus gets a much better result than effectively everyone else with a Hellenistic army and also why it isn’t enough to actually defeat the Romans (or the Carthaginians, who he also fights). As I noted last time, I am going to lean a bit in this reconstruction on P.A. Kent, A History of the Pyrrhic War (2020), which does an admirable job of untangling our deeply tangled and honestly quite rubbish sources for this important conflict.

Believe it or not, we are actually going to believe Plutarch in a fair bit of this. So, you know, brace yourself for that.

Now, Pyrrhus’ campaigns wouldn’t have been possible, as we’ll note, without financial support from Ptolemy II Philadelphus, Antigonus II Gonatus and Ptolemy Keraunos. So, as always, if you want to help me raise an Epirote army to invade Italy (NATO really complicates this plan, as compared to the third century, I’ll admit), you can support this project on Patreon.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Phalanx’s Twilight, Legion’s Triumph, Part IIIb: Pyrrhus”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2024-03-08.

July 6, 2024

QotD: The Roman Republic at war … many wars … many simultaneous wars

With the end of the Third Samnite War in 290 and the Pyrrhic War in 275, Rome’s dominance of Italy and the alliance system it constructed was effectively complete. This was terribly important because the century that would follow, stretching from the start of the First Punic War in 264 to the end of the Third Macedonian War in 168 (one could argue perhaps even to the fall of Numantia in 133) put the Roman military system and the alliance that underpinned it to a long series of sore tests. This isn’t the place for a detailed recounting of the wars of this period, but in brief, Rome would fight major wars with three of the four other Mediterranean great powers: Carthage (264-241, 218-201, 149-146), Antigonid Macedon (214-205, 200-196, 172-168, 150-148) and the Seleucid Empire (192-188), while at the same time engaged in a long series of often quite serious wars against non-state peoples in Cisalpine Gaul (modern north Italy) and Spain, among others. It was a century of iron and blood that tested the Roman system to the breaking point.

It certainly cannot be said of this period that the Romans always won the battles (though they won more than their fair share, they also lost some very major ones quite badly) or that they always had the best generals (though, again, they tended to fare better than average in this department). Things did not always go their way; whole armies were lost in disastrous battles, whole fleets dashed apart in storms. Rome came very close at points to defeat; in 242, the Roman treasury was bankrupt and their last fleet financed privately for lack of funds (Plb. 1.59.6-7). During the Second Punic War, at one point the Roman censors checked the census records of every Roman citizen liable for conscription and found only 2,000 men of prime military age (out of perhaps 200,000 or so; Taylor (2020), 27-41 has a discussion of the various reconstructions of Roman census figures here) who hadn’t served in just the previous four years (Liv. 24.18.8-9). In essence the Romans had drafted everyone who could be drafted (and the 2,000 remainders were stripped of citizenship on the almost certainly correct assumption that the only way to not have been drafted in those four years but also not have a recorded exemption was intentional draft-dodging).

And the military demands made on Roman armies and resources were exceptional. Roman forces operated as far east as Anatolia and as far west as Spain at the same time. Livy, who records the disposition of Roman forces on a year-for-year basis during much of this period (we are uncommonly well informed about the back half of the period because those books of Livy mostly survive), presents some truly preposterous Roman dispositions. Brunt (Italian Manpower (1971), 422) figures that the Romans must have had something like 225,000 men under arms (Romans and socii) each year between 214 and 212, immediately following a series of three crushing defeats in which the Romans probably lost close to 80,000 men. I want to put that figure in perspective for a moment: Alexander the Great invaded the entire Persian Empire with an army of 43,000 infantry and 5,500 cavalry. The Romans, having lost close to Alexander’s entire invasion force twice over, immediately raised more than four times as many men and kept fighting.

These armies were split between a bewildering array of fronts (e.g. Liv 24.10 or 25.3): multiple armies in southern Italy (against Hannibal and rebellious socii now supporting him), northern Italy (against the Cisalpine Gauls, who also backed Hannibal) and Sicily (where Syracuse threatened revolt) and Spain (a Carthaginian possession) and Illyria (fighting the Antigonids) and with fleets active in both the Adriatic and Tyrrhenian Sea supporting those operations. And of course a force defending Rome itself because did I mention Hannibal was in Italy?

If you will pardon me embellishing a Babylon 5 quote, “Only an idiot fights a war on two fronts. Only the heir to the throne of the kingdom of idiots would fight a war on twelve fronts.” And apparently, only the Romans would then win that war anyway.

(I should note that, for those interested in reading up on this, the state-of-the-art account of Rome’s ability to marshal these truly incredible amounts of resources and especially men is the aforementioned, M. Taylor, Soldiers & Silver (2020), which presents the consensus position of scholars better than anything else out there. I’d be remiss if I didn’t note that my own book project takes aim at this consensus and hopes to overturn parts of it, but seeing as how my book isn’t done, for now Taylor holds the field (also it’s a good book which is why I recommended it)).

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: The Queen’s Latin or Who Were the Romans, Part II: Citizens and Allies”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-06-25.

June 30, 2024

Why Democracies Always Fail

The Why Minutes

Published Feb 21, 2024Why do democracies have a pesky habit of destroying themselves?

May 19, 2024

Alexander III of Macedon … usually styled “Alexander the Great”

In the most recent post at A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, Bret Devereaux considers whether the most famous king of Macedon deserves his historic title:

Alexander the Great

Detail from the Alexander Mosaic in the House of the Faun in Pompeii, attributed to the first century BC, via Wikimedia Commons.

I want to discuss his reign with that title, “the Great” (magnus in Latin or μέγας in Greek) stripped off, as Alexander III rather than merely assuming his greatness. In particular, I want to open the question of if Alexander was great and more to the point, if he was, what does that imply about our definitions of greatness?

It is hardly new for Alexander III to be the subject of as much mythology as fact; Alexander’s life was the subject of mythological treatment within living memory. Plutarch (Alex. 46.4) relates an episode where the Greek historian Onesicritus read aloud in the court of Lysimachus – then king of Thrace, but who had been one of Alexander’s somatophylakes (his personal bodyguards, of which there were just seven at at time) – his history of Alexander and in his fourth book reached the apocryphal story of how Alexander met the Queen of the Amazons, Thalestris, at which Lysimachus smiled and asked, “And where was I at the time?” It must have been strange to Lysimachus, who had known Alexander personally, to see his friend and companion become a myth before his eyes.

Then, of course, there are the modern layers of mythology. Alexander is such a well-known figures that it has been, for centuries, the “doing thing” to attribute all manner of profound sounding quotes, sayings and actions to him, functionally none of which are to be found in the ancient sources and most of which, as we’ll see, run quite directly counter to his actual character as a person.

So, much as we set out to de-mystify Cleopatra last year, this year I want to set out – briefly – to de-mystify Alexander III of Macedon. Only once we’ve stripped away the mythology and found the man can we then ask that key question: was Alexander truly great and if so, what does that say not about Alexander, but about our own conceptions of greatness?

Because this post has turned out to run rather longer than I expected, I’m going to split into two parts. This week, we’re going to look at some of the history of how Alexander has been viewed – the sources for his life but also the trends in the scholarship from the 1800s to the present – along with assessing Alexander as a military commander. Then we’ll come back next week and look at Alexander as an administrator, leader and king.

[…]

Sources

As always, we are at the mercy of our sources for understanding the reign of Alexander III. As noted above, within Alexander’s own lifetime, the scale of his achievements and impacts prompted the emergence of a mythological telling of his life, a collection of stories we refer to collectively now as the Alexander Romance, which is fascinating as an example of narrative and legend working across a wide range of cultures and languages, but is fundamentally useless as a source of information about Alexander’s life.

That said, we also know that several accounts of Alexander’s life and reign were written during his life and immediately afterwards by people who knew him and had witnessed the events. Alexander, for the first part of his campaign, had a court historian, Callisthenes, who wrote a biography of Alexander which survived his reign (Polybius is aware – and highly critical – of it, Polyb. 12. 17-22), though Callisthenes didn’t: he was implicated (perhaps falsely) in a plot against Alexander and imprisoned, where he died, in 327. Unfortunately, Callisthenes’ history doesn’t survive to the present (and Polybius sure thinks Callisthenes was incompetent in describing military matters in any event).

More promising are histories written by Alexander’s close companions – his hetairoi – who served as Alexander’s guards, elite cavalry striking force, officers and council of war during his campaigns. Three of these wrote significant accounts of Alexander’s campaigns: Aristobulus,1 Alexander’s architect and siege engineer, Nearchus, Alexander’s naval commander, and Ptolemy, one of Alexander’s bodyguards and infantry commanders, who will become Ptolemy I Soter, Pharaoh of Egypt. Of these, Aristobulus and Ptolemy’s works were apparently campaign histories covering the life of Alexander, whereas Nearchus wrote instead of his own voyages by sea down the Indus River, the Indian Ocean and the Persian Gulf which he called the Indike.

And you are now doubtless thinking, “amazing, three contemporary accounts, that’s awesome!” So I hope you will contain your disappointment when I follow with the inevitable punchline: none of these three works survives. We also know a whole slew of other, less reliable sounding histories (Plutarch lists works by Cleitarchus, Polycleitus, Onesicritus, Antigenes, Ister, Chares, Anticleides, Philo, two different Philips, Hecataeus, and Duris) do not survive either.

So what do we have?

Fundamentally, our knowledge of Alexander the Great is premised on four primary later works who wrote when all of these other sources (particularly Ptolemy and Aristobulus) still survived. These four authors are (in order of date): Diodorus Siculus (writing in the first century BC), Quintus Curtius Rufus (mid-first cent. AD), Plutarch (early second century AD) and Arrian (Lucius Flavius Arrianus, writing in the early second century AD). Of these, Diodorus’ work, the Bibliotheca historica is a “universal history”, which of course means it is a mile wide and only an inch deep, but Book 17, which covers Alexander’s life, is intact and complete. Curtius Rufus’ work survives only incompletely, with substantial gaps in the text, including all of the first two books.

Plutarch’s Life of Alexander survives intact and is the most substantial of his biographies, but it is, like all of his Parallel Lives, relatively brief and also prone to Plutarch’s instinct to bend a story to fit his moralizing aims in writing. Which leaves, somewhat ironically, the last of these main sources, Arrian. Arrian was a Roman citizen of Anatolian extraction who entered the Senate in the 120s and was consul suffectus under Hadrian, probably in 130. He was then a legatus (provincial governor/military commander in Cappadocia, where Dio reports (69.15.1) that he checked an invasion by the Alani (a Steppe people). Arrian’s history, the Anabasis Alexandrou (usually rendered “Campaigns of Alexander”)2 comes across as a fairly serious, no-nonsense effort to compile the best available sources, written by an experienced military man. Which is not to say Arrian is perfect, but his account is generally regarded (correctly, I’d argue) as the most reliable of the bunch, though any serious scholarship on Alexander relies on collating all four sources and comparing them together.

Despite that awkward source tradition, what we have generally leaves us fairly well informed about Alexander’s actions as king. While we’d certainly prefer to have Ptolemy or Aristobolus, the fact that we have four writers all working from a similar source-base is an advantage, as they take different perspectives. Moreover, a lot of the things Alexander did – founding cities, toppling the Achaemenid Empire, failing in any way to prepare for succession – leave big historical or archaeological traces that are easy enough to track.

1. This is as good a place as any to make a note about transliteration. Almost every significant character in Alexander’s narrative has a traditional transliteration into English, typically based on how their name would be spelled in Latin. Thus Aristobulus, instead of the more faithful Aristoboulos (for Ἀριστόβουλος). The trend in Alexander scholarship today is, understandably, to prefer more faithful Greek transliterations, thus rendering Parmenion (rather than Parmenio) or Seleukos (rather than Seleucus). I think, in scholarship, this is a good trend, but since this is a public-facing work, I am going to largely stick to the traditional transliterations, because that’s generally how a reader would subsequently look up these figures.

2. An ἀνάβασις is a “journey up-country”, but what Arrian is invoking here is Xenophon’s account of his own campaign with the 10,000, the original Anabasis; Arrian seems to have fashioned himself as a “second Xenophon” in a number of ways.

April 29, 2024

Greek History and Civilization, Part 7 – Alexander

seangabb

Published Apr 28, 2024This seventh lecture in the course covers the career of Alexander the Great and its consequences for the world.

(more…)

April 12, 2024

Greek History and Civilization, Part 6 – The Search for Stability

seangabb

Published Apr 7, 2024This sixth lecture in the course deals with the period of Greek history between the end of the Persian Wars and the assassination of Philip II of Macedon.

(more…)

February 13, 2024

QotD: War elephant logistics

From trunk to tail, elephants are a logistics nightmare.

And that begins almost literally at birth. For areas where elephants are native, nature (combined, typically, with the local human terrain) create a local “supply”. In India this meant the elephant forests of North/North-Eastern India; the range of the North African elephant (Loxodonta africana pharaohensis, the most likely source of Ptolemaic and Carthaginian war elephants) is not known. Thus for many elephant-wielding powers, trade was going to always be a key source for the animals – either trade with far away kingdoms (the Seleucids traded with the Mauyran Indian kingdom for their superior Asian elephants) or with thinly ruled peripheral peoples who lived in the forests the elephants were native to.

(We’re about to get into some of the specifics of elephant biology. If you are curious on this topic, I am relying heavily on R. Sukumar, The Asian Elephant: Ecology and Management (1989). I’ve found that information on Asian elephants (Elephas maximus) much easier to come by than information on African elephants (Loxodonta africana and Loxodonta cyclotis).)

In that light, creating a breeding program – as was done with horses – seems like a great idea. Except there is one major problem: a horse requires about four years to reach maturity, a mare gestates a foal in eleven months and can go into heat almost immediately thereafter. By contrast, elephants reach adulthood after seventeen years, take 18-22 months to gestate and female elephants do not typically mate until their calf is weaned, four to five years after its birth. A ruler looking to build a stable of cavalry horses thus may start small and grow rapidly; a ruler looking to build a corps of war elephants is looking at a very slow process. This is compounded by the fact that elephants are notoriously difficult to breed in captivity. There is some speculation that the Seleucids nonetheless attempted this at Apamea, where they based their elephants – in any event, they seem to have remained dependent on imported Indian elephants to maintain the elephant corps. If a self-sustaining elephant breeding program for war elephants was ever created, we do not know about it.

To make matters worse, elephants require massive amounts of food and water. In video-games, this is often represented through a high elephant “upkeep” cost – but this often falls well short of the reality of keeping these animals for war. Let’s take Total War: Rome II as an example: a unit of Roman (auxiliary) African elephants (12 animals), costs 180 upkeep, compared to 90 to 110 upkeep for 80 horses of auxiliary cavalry (there are quite a few types) – so one elephant (with a mahout) costs 15 upkeep against around 1.25 for a horse and rider (a 12:1 ratio). Paradox’s Imperator does something similar, with a single unit of war elephants requiring 1.08 upkeep, compared to just 0.32 for light cavalry; along with this, elephants have a heavy “supply weight” – twice that of an equivalent number of cavalry (so something like a 2:1 or 3:1 ratio of cost).

Believe it or not, this understates just how hungry – and expensive – elephants are. The standard barley ration for a Roman horse was 7kg of barley per day (7 Attic medimnoi per month; Plb. 6.39.12); this would be supplemented by grazing. Estimates for the food requirements of elephants vary widely (in part, it is hard to measure the dietary needs of grazing animals), but elephants require in excess of 1.5% of their body-weight in food per day. Estimates for the dietary requirements of the Asian elephant can range from 135 to 300kg per day in a mix of grazing and fodder – and remember, the preference in war elephants is for large, mature adult males, meaning that most war elephants will be towards the top of this range. Accounting for some grazing (probably significantly less than half of dietary needs) a large adult male elephant is thus likely to need something like 15 to 30 times the food to sustain itself as a stable-fed horse.

In peacetime, these elephants have to be fed and maintained, but on campaign the difficulty of supplying these elephants on the march is layered on top of that. We’ve discussed elsewhere the difficulty in supplying an army with food, but large groups of elephants magnify this problem immensely. The 54 elephants the Seleucids brought to Magnesia might have consumed as much food as 1,000 cavalrymen (that’s a rider, a horse and a servant to tend that horse and its rider).

But that still understates the cost intensity of elephants. Bringing a horse to battle in the ancient world required the horse, a rider and typically a servant (this is neatly implied by the more generous rations to cavalrymen, who would be expected to have a servant to be the horse’s groom, unlike the poorer infantry, see Plb. above). But getting a war elephant to battle was a team effort. Trautmann (2015) notes that elephant stables required riders, drivers, guards, trainers, cooks, feeders, guards, attendants, doctors and specialist foot-chainers (along with specialist hunters to capture the elephants in the first place!). Many of these men were highly trained specialists and thus had to be quite well paid.

Now – and this is important – pre-modern states are not building their militaries from the ground up. What they have is a package of legacy systems. In Rome’s case, the defeat of Carthage in the Second Punic War resulted in Rome having North African allies who already had elephants. Rome could accept those elephant allied troops, or say “no” and probably get nothing to replace them. In that case – if the choice is between “elephants or nothing” – then you take the elephants. What is telling is that – as Rome was able to exert more control over how these regions were exploited – the elephants vanished, presumably as the Romans dismantled or neglected the systems for capturing and training them (which they now controlled directly).

That resolves part of our puzzle: why did the Romans use elephants in the second and early first centuries B.C.? Because they had allies whose own military systems involved elephants. But that leaves the second part of the puzzle – Rome doesn’t simply fail to build an elephant program. Rome absorbs an elephant program and then lets it die. Why?

For states with scarce resources – and all states have scarce resources – using elephants meant not directing those resources (food, money, personnel, time and administrative capacity) for something else. If the elephant had no other value (we’ll look at one other use next week), then developing elephants becomes a simple, if difficult, calculation: are the elephants more likely to win the battle for me than the equivalent resources spent on something else, like cavalry. As we’ve seen above, that boils down to comparisons between having just dozens of elephants or potentially hundreds or thousands of cavalry.

The Romans obviously made the bet that investing in cavalry or infantry was a better use of time, money and resources than investing in elephants, because they thought elephants were unlikely to win battles. Given Rome’s subsequent spectacular battlefield success, it is hard to avoid the conclusion they were right, at least in the Mediterranean context.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: War Elephants, Part II: Elephants against Wolves”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2019-08-02.

February 11, 2024

QotD: Learning and re-learning the bloody art of war

The values composing civilization and the values required to protect it are normally at war. Civilization values sophistication, but in an armed force sophistication is a millstone.

The Athenian commanders before Salamis, it is reported, talked of art and of the Acropolis, in sight of the Persian fleet. Beside their own campfires, the Greek hoplites chewed garlic and joked about girls.

Without its tough spearmen, Hellenic culture would have had nothing to give the world. It would not have lasted long enough. When Greek culture became so sophisticated that its common men would no longer fight to the death, as at Thermopylae, but became devious and clever, a horde of Roman farm boys overran them.

The time came when the descendants of Macedonians who had slaughtered Asians till they could no longer lift their arms went pale and sick at the sight of the havoc wrought by the Roman gladius Hispanicus as it carved its way toward Hellas.

The Eighth Army, put to the fire and blooded, rose from its own ashes in a killing mood. They went north, and as they went they destroyed Chinese and what was left of the towns and cities of Korea. They did not grow sick at the sight of blood.

By 7 March they stood on the Han. They went through Seoul, and reduced it block by block. When they were finished, the massive railway station had no roof, and thousands of buildings were pocked by tank fire. Of Seoul’s original more than a million souls, less than two hundred thousand still lived in the ruins. In many of the lesser cities of Korea, built of wood and wattle, only the foundation, and the vault, of the old Japanese bank remained.

The people of Chosun, not Americans or Chinese, continued to lose the war.

At the end of March the Eighth Army was across the parallel.

General Ridgway wrote, “The American flag never flew over a prouder, tougher, more spirited and more competent fighting force than was Eighth Army as it drove north …”

Ridgway had no great interest in real estate. He did not strike for cities and towns, but to kill Chinese. The Eighth Army killed them, by the thousands, as its infantry drove them from the hills and as its air caught them fleeing in the valleys.

By April 1951, the Eighth Army had again proved Erwin Rommel’s assertion that American troops knew less but learned faster than any fighting men he had opposed. The Chinese seemed not to learn at all, as they repeated Chipyong-ni again and again.

Americans had learned, and learned well. The tragedy of American arms, however, is that having an imperfect sense of history Americans sometimes forget as quickly as they learn.

T.R. Fehrenbach, This Kind of War: A Study in Unpreparedness, 1963.

November 28, 2023

Pierre Trudeau and Canada’s choice to become an international featherweight in the 1970s

In The Line, Jen Gerson endures a foreign policy speech from Mélanie Joly that takes her on a weird journey through some of Canada’s earlier foreign policy headscratchers … usually leading back to Justin Trudeau’s late father:

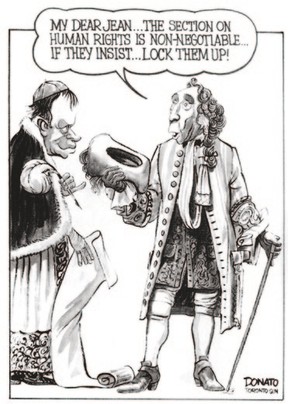

A Toronto Sun editorial cartoon by Andy Donato during Pierre Trudeau’s efforts to pass the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. You can certainly see where Justin Trudeau learned his approach to human rights.

If I saw a statue of P.E.T. on the roof of a foreign affairs building that looked like it were competing for a 10th place spot in the Eurovision tourney, I don’t know how I’d feel: embarrassed, touched, certainly too polite to say anything honest. I probably wouldn’t be so struck with awe by the sight that I’d be keen to shoehorn the anecdote into a major policy speech in front of the Economic Club.

And yet.

Joly’s speech was striking in that it could be divided into two distinct parts: The first half was a cogent and clear-eyed examination of the state of play of the world, one that acknowledged a fundamental shift in the assumptions that underpin the global order. Nothing one couldn’t glean from the Economist, but grounded nonetheless. The global order is shifting, the stakes have increased, and the world is going to be marked by growing unpredictability.

“Now more than ever, soft and hard power are important,” Joly noted, correctly, ignoring the fact that Canada increasingly has neither, and doesn’t seem to be doing much about that.

And this brings us to the second half of the speech, which was an attempt to spell out the way Canada will navigate this shift, by situating itself as both a Western ally and an honest broker: we are to defend our national interests and our values, while also engaging with entities and countries whose values and interests radically diverge from our own. “We cannot afford to close ourselves off from those with whom we do not agree,” Joly said. “I am a door opener, not a door closer.”

This was clearly intended to be analogous to the elder Trudeau’s historic policy of seeking cooperation with non-aligned countries — countries that declined to join either the Communist or the Western blocs throughout the Cold War.

[…]

If our closest allies treat us like ginger step-children as a result of our own obliviousness and uselessness, our platitude-spewing ruling class is going to seek closer relationships in darker places: in economic ties with China, and in finding international prestige via small and middling regional powers or blocs whose values and interests are, by necessity or choice, far more malleable than our own.

These cute turns of phrase are a matter of domestic salesmanship only. “Pragmatic diplomacy” is a thick lacquer on darker arts.

Which brings us back to Macedonia, again. Or North Macedonia, if you’re a stickler.

Before it declared independence in 1991, Macedonia was a republic within the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. During much of Trudeau Sr.’s time, Yugoslavia was led by Josip Tito, a Communist revolutionary who broke with Stalin and spearheaded a movement of non-aligned countries, along with the leaders of India, Egypt, Ghana, and Indonesia. Tito was one of several despotic and authoritarian leaders with whom Trudeau Sr. sought to ingratiate himself to navigate the global order.

P.E.T.’s most ardent supporters maintain a benevolent amnesia about just how radical Trudeau Sr. was relative not only to modern standards, but to world leaders at the time.

During the 1968 election, Trudeau promised to undertake a sweeping review of Canada’s foreign affairs, including taking “a hard look” at NATO, and addressing China’s exclusion from the international community.

In 1969, America elected Richard Nixon a bombastic, controversial, and corrupt president who forced Canada examine the depth of its special relationship with its southern neighbour. At the time, this was termed “Nixon shock.” And it could only have furthered Trudeau Sr.’s skepticism of American hegemony.

It was in this environment of extraordinary uncertainty, and shifting global assumptions and alliances, that Trudeau Sr. called for a new approach to Canadian foreign policy. He wanted a Canada that saw itself as a Pacific power, more aligned to Asia (and China). Trudeau also wanted stronger relationships with Western Europe and Latin America, to serve as countervailing forces to American influence.