I was very saddened to see the news, but it explains why the band retired:

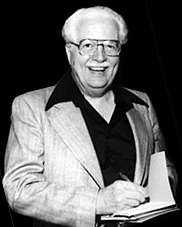

Neil Peart, the virtuoso drummer and lyricist for Rush, died Tuesday, January 7th, in Santa Monica, California, at age 67, according to Elliot Mintz, a family spokesperson. The cause was brain cancer, which Peart had been quietly battling for three-and-a-half years. A representative for the band confirmed the news to Rolling Stone.

Peart was one of rock’s greatest drummers, with a flamboyant yet precise style that paid homage to his hero, the Who’s Keith Moon, while expanding the technical and imaginative possibilities of his instrument. He joined singer-bassist Geddy Lee and guitarist Alex Lifeson in Rush in 1974, and his musicianship and literate, philosophical lyrics — which initially drew on Ayn Rand and science fiction, and later became more personal and emotive — helped make the trio one of the classic-rock era’s essential bands. His drum fills on songs like “Tom Sawyer” were pop hooks in their own right, each one an indelible mini-composition; his lengthy drum solos, carefully constructed and packed with drama, were highlights of every Rush concert.

In a statement released Friday afternoon, Lee and Lifeson called Peart their “friend, soul brother and bandmate over 45 years,” and said he had been “incredibly brave” in his battle with glioblastoma, an aggressive form of brain cancer. “We ask that friends, fans, and media alike understandably respect the family’s need for privacy and peace at this extremely painful and difficult time,” Lee and Lifeson wrote. “Those wishing to express their condolences can choose a cancer research group or charity of their choice and make a donation in Neil Peart’s name. Rest in peace, brother.”

A rigorous autodidact, Peart was also the author of numerous books, beginning with 1996’s The Masked Rider: Cycling in West Africa, which chronicled a 1988 bicycle tour in Cameroon — in that memoir, he recalled an impromptu hand-drum performance that drew an entire village to watch.

Peart never stopped believing in the possibilities of rock (“a gift beyond price,” he called it in Rush’s 1980 track “The Spirit of Radio”) and despised what he saw as over-commercialization of the music industry and dumbed-down artists he saw as “panderers.” “It’s about being your own hero,” he told Rolling Stone in 2015. “I set out to never betray the values that 16-year-old had, to never sell out, to never bow to the man. A compromise is what I can never accept.”

Update: At AIER Peter C. Earle pays tribute to Peart’s life and work.

The announcement of the death of Rush drummer Neil Peart came as a tremendous shock. Having only retired about four years ago, so many fans of Rush (myself included) had convinced ourselves that this was a temporary hiatus, and that in a year or two – eventually, at any rate – there would be an announcement of a new album, a short tour, or some other project. Surely musicians of their virtuosity and passion couldn’t stay away from the studio or stage for long. But now we know we were wrong, and we know why.

It was revealed that Neil had been battling a brain tumor for over three years. Characteristically, he, his family, and friends (among the closest of whom, Rush vocalist/bass player Geddy Lee and guitarist Alex Lifeson) upheld his desire for privacy. I haven’t done the math as to whether Neil’s illness was likely a causative factor in the decision to retire, or whether it seems to have come along not long after the decision to retire.

[…]

In his role as the lyricist of Rush, Peart took on such topics as pernicious nationalism (“Territories”), mass hysteria (“Witch Hunt”), the division between constructive and destructive belief (“Faithless”), the fall of Communism (“Heresy”), conflict and power (“The Trees”), the horrors of totalitarian rule (“2112,” “Red Sector A”) and many allusions to individual liberty (“Tom Sawyer,” “Anthem,” “The Analog Kid,” “Finding My Way,” “Caravan”). He did so via lyrics which artfully and passionately evinced those sentiments; sentiments which early on suggested Objectivist perspectives, but over time developed into what he called “Bleeding Heart” libertarianism:

I call myself a bleeding heart libertarian. Because I do believe in the principles of Libertarianism as an ideal – because I’m an idealist. Paul Theroux’s definition of a cynic is a disappointed idealist. So as you go through past your twenties, your idealism is going to be disappointed many many times. And so, I’ve brought my view and also – I’ve just realized this – Libertarianism as I understood it was very good and pure and we’re all going to be successful and generous to the less fortunate and it was, to me, not dark or cynical. But then I soon saw, of course, the way that it gets twisted by the flaws of humanity. And that’s when I evolve now into … a bleeding heart Libertarian. That’ll do.

Neil, through his lyrics, managed to do what so many lyricists and writers – even, perhaps especially, so many libertarian intellectuals – fail to do: make liberty neither an alien fixture, a flat slogan, or a utopian slog. It is a way of thinking and living, and one which not only doesn’t ignore, but embraces the flaws and frailty of humanity, tempering realism with hope and optimism.