To sound generally foreign, omit elisions and contractions normally used by native speakers. Type “I do not think I have the time” rather than “I don’t think I have time”.

To sound German, put commas in places that do not correspond to speech pauses in English. “I do not know, how he could have believed that.”

To sound Russian, omit definite or indefinite articles. “No, you cannot have cheeseburger.”

To sound like a speaker of Hindi or Urdu or one of the related languages, emit wordy run-on sentences that begin with “Esteemed sir”, like: “Esteemed sir, I would be grateful if you could direct me towards a good book on Python because I am attempting to learn programming.”

Understand, none of these errors actually interferes with comprehension. I’ve found that these second-language speakers are often more worried about the quality of their English than they need to be.

Eric S. Raymond, “How to Type with a Foreign Accent”, Armed and Dangerous, 2009-06-12.

June 10, 2018

QotD: Typing with a foreign accent

May 29, 2018

ESR’s thumbnail sketch on the origins of the Indo-European language families

When you mash historical linguistics hard enough into paleogenetics, interesting things fall out:

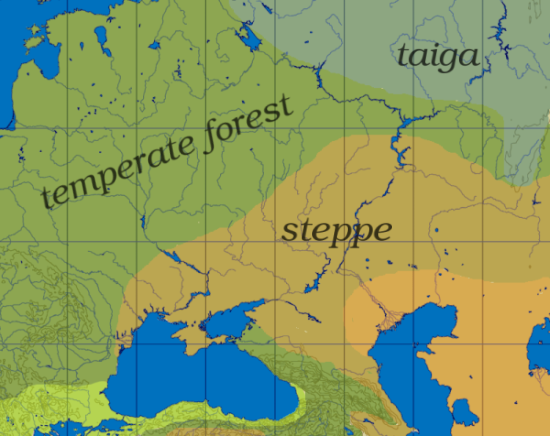

The steppe extends roughly from the Dniepr to the Ural or 30° to 55° east longitude, and from the Black Sea and the Caucasus in the south to the temperate forest and taiga in the north, or 45° to 55° north latitude.

Via Wikipedia

What we can now say pretty much for sure: Proto-Indo-European was first spoken on the Pontic Steppes around 4000 BCE. That’s the grasslands north of the Black Sea and west of the Urals; today, it’s the Ukraine and parts of European Russia. The original PIE speakers (which we can now confidently identify with what archaeologists call the Yamnaya culture) were the first humans to domesticate horses.

And – well, basically, they were the first and most successful horse barbarians. They invaded Europe via the Danube Valley and contributed about half the genetic ancestry of modern Europeans – a bit more in the north, where they almost wiped out the indigenes; a bit less in the south where they mixed more with a population of farmers who had previously migrated in on foot from somewhere in Anatolia.

The broad outline isn’t a new idea. 400 years ago the very first speculations about a possible IE root language fingered the Scythians, Pontic-Steppe descendants in historical times of the original PIE speakers – with a similar horse-barbarian lifestyle. It was actually a remarkably good guess, considering. The first version of the “modern” steppe-origin hypothesis – warlike bronze-age PIE speakers domesticate the horse and overrun Europe at sword- and spear-point – goes back to 1926.

But since then various flavors of nationalist and nutty racial theorist have tried to relocate the PIE urheimat all over the map – usually in the nut’s home country. The Nazis wanted to believe it was somewhere in their Greater Germany, of course. There’s still a crew of fringe scientists trying to pin it to northern India, but the paleogenetic evidence craps all over that theory (as Cochran explains rather gleefully – he does enjoy calling bullshit on bullshit).

Then there have been the non-nutty proposals. There was a scientist named Colin Renfrew who for many years (quite respectably) pushed the theory that IE speakers walked into Europe from Anatolia along with farming technology, instead of riding in off the steppes brandishing weapons like some tribe in a Robert E. Howard novel.

Alas, Renfrew was wrong. It now looks like there was such a migration, but those people spoke a non-IE language (most likely something archaically Semitic) and got overrun by the PIE speakers riding in a few thousand years later. Cochran calls these people “EEF” (Eastern European Farmers) and they’re most of the non-IE half of modern European ancestry. Basque is the only living language that survives from EEF times; Otzi the Iceman was EEF, and you can still find people with genes a lot like his in the remotest hills of Sardinia.

Even David Anthony, good as he is about much else, seems rather embarrassed and denialist about the fire-and-sword stuff. Late in his book he spins a lot of hopeful guff about IE speakers expanding up the Danube peacefully by recruiting the locals into their culture.

Um, nope. The genetic evidence is merciless (though, to be fair, Anthony can’t have known this). There’s a particular pattern of Y-chromosome and mitochondrial DNA variation that you only get in descendant population C when it’s a mix produced because aggressor population A killed most or all of population B’s men and took their women. Modern Europeans (C) have that pattern, the maternal line stuff (B) is EEF, and the paternal-line stuff (A) is straight outta steppe-land; the Yamnaya invaders were not gentle.

How un-gentle were they? Well…this paragraph is me filling in from some sources that aren’t Anthony or Cochran, now. While Europeans still have EEF genes, almost nothing of EEF culture survived in later Europe beyond the plants they domesticated, the names of some rivers, and (possibly) a murky substratum in some European mythologies.

The PIE speakers themselves seem to have formed, genetically, when an earlier population called the Ancient Northern Eurasians did a fire-and-sword number (on foot, that time) on a group of early farmers from the Fertile Crescent. Cochrane sometimes calls the ANEs “Hyperboreans” or “Cimmerians”, which is pretty funny if you’ve read your Howard.

May 14, 2018

QotD: Words and ideas matter

The way we talk and write – the words we use – what we say and what we don’t say – matter. Of course, the process of articulating thoughts helps each of us who articulates (and that is every human being) to better form thoughts that are otherwise fuzzy and amorphous. More importantly, what we express to others not only informs others of facts, instructions, and perspectives that they would not learn were we not to express our thoughts to them, our talking also expresses and, in doing so, reinforces specific ethical values.

Each and every time you say with a smile “thank you” to the supermarket cashier who tallies your order you add a little more dignity to that person’s life and occupation – and to the social estimation of that and related occupations. Each and every time you tell a homophobic or anti-immigrant joke, you detract from the social valuation of homosexuals or of immigrants. Through our talk we humans are constantly raising the social valuation of some peoples and things and lowering the social valuation of other peoples and things. Your words, individually, might have no detectable impact, but by signaling to your hearers or readers what you regard to be acceptable and unacceptable – honorable and dishonorable – important and insignificant – productive and unproductive – polite and crude – true and false – good and bad – you influence their perceptions and evaluations, if only ever so slightly. If, for example, you express admiration for a hard-working entrepreneur and do so with no trace of envy of that entrepreneur’s monetary success, your audience (be it one person or a million people) becomes a bit more inclined to regard entrepreneurs favorably and to not suppose that successful entrepreneurs’ profits are to be envied.

Obviously, the relation of the speaker to the audience matters. The effect of a mother’s words on the attitudes of her young child is greater than the effect of those same words, spoken by the same woman, to some other-woman’s child. The effect of words about widgets spoken by someone publicly regarded to be an expert in widgetry is greater than is the effect of words about widgets spoken by someone who is not regarded as having expertise in widgetry.

Ideas and attitudes matter. They matter greatly. And ideas and attitudes are transmitted chiefly by words. It is this reality above all that causes me distress when I hear or read someone with a degree in economics (or who is otherwise regarded to be expert in economics) get fundamental economics wrong. When some economist asserts that a country’s growing trade deficit destroys jobs, that’s simply wrong – but the expression of that false notion, especially by an “economist,” contributes to the public’s fear of international trade. When some other economist says that “[t]here’s just no evidence that raising the minimum wage costs jobs,” that, in this case, is not only indisputably wrong but is almost certainly an outright lie – but this economist’s lie contributes to the public’s false belief that hikes in minimum wages are all gain with no risk of loss for low-skilled workers. When economists talk and write, as they too often do, as if government officials possess superhuman capacities to care about strangers and to know enough to intervene productively into those strangers’ affairs, that’s wrong – but such talking and writing gives more phoolish credence to the false notion that state power is an especially trustworthy cure for life’s ailments, large and small.

Don Boudreaux, “Quotation of the Day…”, Café Hayek, 2016-08-01.

May 10, 2018

QotD: Langue de bois

The attendees [of a medical leadership conference] would learn about something called “lean management,” one feebly-attempted definition of which is as follows:

If someone tells you that “lean management is this” and not something else, if someone puts it in a box and ties a bow around it and presents it in a neat package with four walls around it, then that someone knows not of what they speak. Why? Because it is in motion and not a framed picture hanging on the wall. It is a melody, a rhythm, and not a single note.

This is the mysticism of apparatchiks, the romanticism of bureaucrats, the poetry of clerks. From my limited observations of management in public hospitals and other parts of the public health care system, it seeks to be not lean, in the commonly used sense of the word, but fat, indeed as fat as possible; nor are large private institutions very much different.

It seems, then, that we have entered, gradually and without any central direction or decree, a golden age of langue de bois or even of Newspeak. Langue de bois is the pompous, vague, and abstract words that have some kind of connotation but no real denotation used by those who have to hide their real motives and activities by a smokescreen of scientific- or benevolent-sounding verbiage. Newspeak is the language in Nineteen Eighty-Four whose object is to limit human minds to a few simple politically permissible thoughts, excluding all others, and making doublethink — the frictionless assent to incompatible propositions — part of everyday mentation.

Langue de bois and Newspeak are no longer languages into which normal thought must be translated; rather they have become the languages in which thought itself, or rather cerebral activity, takes place, at least in the upper echelons of the bureaucracy that rules us. If you ask someone who speaks either of them to translate what he has said or written into normal language, it is more than likely he will be unable to do so: His translation will be indistinguishable from the words translated. It is therefore clear that, where culture is concerned, the Soviet Union scored a decisive and probably irreversible victory in the Cold War.

Theodore Dalrymple, “Life de Bois”, Taki’s Magazine, 2016-09-10.

April 15, 2018

QotD: Political words

When one critic writes, “The outstanding feature of Mr. X’s work is its living quality,” while another writes, “The immediately striking thing about Mr. X’s work is its peculiar deadness,” the reader accepts this as a simple difference of opinion. If words like black and white were involved, instead of the jargon words dead and living, he would see at once that language was being used in an improper way. Many political words are similarly abused. The word Fascism has now no meaning except in so far as it signifies “something not desirable.” The words democracy, socialism, freedom, patriotic, realistic, justice have each of them several different meanings which cannot be reconciled with one another. In the case of a word like democracy, not only is there no agreed definition, but the attempt to make one is resisted from all sides. It is almost universally felt that when we call a country democratic we are praising it: consequently the defenders of every kind of regime claim that it is a democracy, and fear that they might have to stop using that word if it were tied down to any one meaning. Words of this kind are often used in a consciously dishonest way. That is, the person who uses them has his own private definition, but allows his hearer to think he means something quite different. Statements like Marshal Pétain was a true patriot, The Soviet press is the freest in the world, The Catholic Church is opposed to persecution, are almost always made with intent to deceive. Other words used in variable meanings, in most cases more or less dishonestly, are: class, totalitarian, science, progressive, reactionary, bourgeois, equality.

George Orwell, “Politics and the English Language”, 1946.

April 2, 2018

The Five Forms of Ancient Egyptian Writing!

The Study of Antiquity and the Middle Ages

Published on 12 Mar 2018In this brief video I discuss the five different forms of writing in Ancient Egypt!

QotD: Is Danish following the same path as Maltese?

… while I was in Denmark I kept tripping over odd facts that pointed to a possibly disturbing conclusion: though the Danes don’t seem to notice it themselves, their native language appears to me to be dying. Here are some of the facts that disturbed me:

- I was told that Danish phonology has been mutating so rapidly over the last 50 years that it is often possible to tell by the accent of an emigre returning to Denmark what decade they left in.

- The Dane with whom I was staying remarked that, having absorbed spoken Danish as a child, he found learning written English easier than learning written Danish.

- Modern Danish is not spoken so much as it is mumbled. Norwegians and Swedes say that Danes talk like they’ve constantly got potatoes in their mouths, and it’s true. Most of the phonemic distinctions you’d think ought to be there from looking at the orthography of written Danish (and which actually are there in Norwegian and Swedish) collapse into a sort of glottalized mud in contemporary spoken Danish.

- At least half the advertising signs in Denmark – and a not inconsiderable percentage of street signs – are in English. Danes usually speak passable English; many routinely code-switch to English even when there are no foreigners involved, in particular for technical discussions.

The overall picture I got of Danish was of a language in an extreme stage of phonological degeneration, extremely divergent from its written form, and functionally unnecessary to many of its younger speakers.

I contemplated all this and thought of Maltese.

Maltese originated as a creole fusing Arabic grammar and structure with loanwords from French and Italian. I have read that since 1800 (and especially since WWII) Maltese has been so heavily influenced by bilingual English and Maltese speakers that much of what is now called “Maltese” is actually “Maltenglish”, rather more like a Maltese-English fusion, with “pure” Maltese only spoken by a dwindling cohort of the very old and very rural. Analysis of this phenomenon is complicated by the fact that the Maltese themselves tend to deny it, insisting for reasons of ethno-tribal identity that they speak more Maltese and less Maltenglish than they actually do.

Based on what I saw and heard in Denmark, I think Danish may be headed down a similar diglossic road, with “pure” Danish preserved as an ethno-tribal museum artifact and common Danish increasingly blending with English until its identity is essentially lost except as a source of picturesque dialect words. For a look at a late stage in this sort of process, consider Lallans, the lowland Scots fusion of Scots Gaelic and English.

Eric S. Raymond, “Is Danish Dying?”, Armed and Dangerous,2009-05-17.

March 23, 2018

The use of the euphemism “grooming”

Mark Steyn from a recent Clubland Q&A session:

If you missed our livestream Clubland Q&A on Tuesday, here’s the action replay. Simply click above for an hour of my answers to questions from Mark Steyn Club members around the planet on various aspects of identity politics, from micro-aggressions at the University of California to macro-aggressions in Telford and Rotherham – with a semantic detour into nano-aggressions and quantum-aggressions. Speaking of semantics, I saw this question after the show ended, from Steyn Club Founding Member Toby Pilling:

If with regard to language, clarity is the remedy (as Orwell would say), shouldn’t the ‘Asian Grooming Gangs’ be re-named ‘Moslem Rape Gangs’? I’ve been trying to make the case that they should at the local council I work for, but over here in the UK one can be hauled in for hate speech at the drop of a hat.

I agree with Messrs Orwell and Pilling on clarity in language, and have never liked the word “grooming”, a bit of social-worker jargonese designed to obscure that what’s going on all over England is mass serial-gang-rape sex-slavery. “Grooming” is, in that sense, a euphemism. An hour or two after yesterday’s show I chanced to stop at the Upper Valley Grill and General Store on an empty strip of road in the middle of the woods in Groton, Vermont, a small town of a thousand souls that feels, if anything, rather smaller than that. And paying at the counter I noticed that they had a can next to the cash register for donations to what the hand-written card called the “Groton Grooming Fund”.

Having just been on the air yakking about Telford, I was momentarily startled. It is, in fact, not a whip-round to enable the gang-rapists to buy more petrol to douse the girls in, but a contribution toward the volunteer group that maintains the local ski and snowmobile trails – ie, they “groom” the snow. Happy the town in which grooming is left to the snowmobile club rather than the Muslim rape gangs. The slogan that greets you on the edge of the village is “Welcome to Groton – Where a Small Town Feels Like a Large Family”, which I always find faintly dispiriting. But it’s better than Telford, where a large town feels like a small prison.

QotD: Canadian English

… everyone knows what Canadians are supposed to sound like: they are a people who pronounce “about” as “aboot” and add “eh” to the ends of sentences.

Unfortunately, that’s wrong. Like, linguistically incorrect. Canadians do not say “aboot.” What they do say is actually much weirder.

Canadian English, despite the gigantic size of the country, is nowhere near as diverse as American English; think of the vast differences between the accents of a Los Angeleno, a Bostonian, a Chicagoan, a Houstonian, and a New Yorker. In Canada, there are some weird pockets: Newfoundland and Labrador speak a sort of Irish-cockney-sounding dialect, and there are some unique characteristics in English-speaking Quebec. But otherwise, linguistically, the country is fairly consistent.

There are a few isolated quirks in Canadian English, like keeping the Britishism “zed” for the last letter of the alphabet, and keeping a hard “agh” sound where Americans would usually say “ah.” (In Canada, “pasta” rhymes with “Mt. Shasta”.) But aside from those quirks, there are two major defining trends in Canadian English: Canadian Raising and the Canadian Shift. The latter is known stateside as the California Shift, and it’s what makes Blink-182 singer Tom DeLonge sound so insane: a systematic migration of vowel sounds resulting in “kit” sounding like “ket,” “dress” sounding like “drass,” and “trap” sounding like “trop.” The SoCal accent, basically, is being replicated almost entirely in Canada.

But the Canadian Shift is minor compared to Canadian Raising, a phenomenon describing the altered sounds of two notable vowel sounds, that has much bigger consequences for the country’s identity, at least in the U.S. That’s where we get all that “aboot” stuff.

Dan Nosowitz, “What’s Going On with the Way Canadians Say ‘About’? It’s not pronounced how you think it is”, Atlas Obscura, 2016-06-01.

March 12, 2018

QotD: Punctuation

The rules [of punctuation] we’re taught in school are the syntactic ones; in these, punctuation is a part of the grammar of written English and the rules for where you put it are derived from grammatical phrase structure and pretty strict. Lynne Truss of Eats, Shoots & Leaves fame is an exponent of this school. But there is another…

Punctuation marks originated from notations used to mark pauses for breath in oral recitations, but 17-to-19th-century grammarians tied them ever more tightly to grammar. There remains a minority position that language pedants call “elocutionary” – that punctuation is properly viewed as markers of speech cadence and intonation. Top-flight copy editors know this: the best one I ever worked with was a syntactic punctuationist on her own hook who noted that I’m an elocutionary punctuationist and then copy-edited in my preferred style rather than hers. (That, my friends, is real professionalism.)

And why am I an elocutionary punctuationist? Because I pay careful attention to speech rhythm and try to convey it in my prose. Not all skilled writers do this, but elocutionary punctuation survives in English because it keeps getting rediscovered for stylistic reasons. Consider Rudyard Kipling or Damon Runyon – two masters of conveying the cadences of spoken English in written form; both used elocutionary punctuation, though perhaps not as a conscious choice.

To an elocutionary punctuationist, the common marks represent speech pauses of increasing length in roughly this order: comma, semicolon, colon, dash, ellipsis, period. Parentheses suggest a vocal aside at lower volume; exclamation point is a volume/emphasis indicator, and question mark means rising tone.

In normal usage, most of the differences between the schools show up in comma placement. But in less usual circumstances, elocutionary punctuationists will cheerfully countenance written utterances that a grammarian would consider technically ill-formed. Here’s an example: “Stop – right – now!” The dashes don’t correspond to phrase boundaries, they’re purely vocal pause markers.

Eric S. Raymond, “Extreme punctuation pedantry”, Armed and Dangerous,

March 7, 2018

Language and the network effect

Tim Worstall in the Dhaka Tribune:

A recent article on the Dhaka Tribune reported that Bangladesh as a country, as an idea, is rather closely linked with the idea of Bangla as a language. Languages having much to do with something economists find fascinating, network effects.

Indeed, we can explain what happens with languages, with Facebook and with currencies all using these same effects. We end up, as we so often do in economics, with the answer: “It depends.”

Let us leave aside those cultural and political issues, the difference between an official language and a mother tongue and mother language. Instead, consider those as networks. Why is it that Facebook has conquered every other form of social media? For the same reason that one fax machine is an expensive paperweight, two allows information to flow, and millions means those millions can communicate with each other.

So it is with anything subject to strong network effects.

We all go on Facebook because everyone else is there, that everyone else is there means more people join it. The standards fax machines use to talk to each other are just the one set of standards precisely so that they can all communicate.

We might think that the same should be true of language. We could all communicate with each other much more easily if there was just the one language used to do so. Often there is a lingua franca which allows this — say, Latin in the past and English now.

But that’s not really how we humans work. Even Bangla is not the same in each and every area of the country, just as English isn’t even in England. There are local dialects which are not mutually intelligible; we use a simplified or standardized version to speak with people from other areas — this is where the “BBC accent” comes from.

The same is true of German for example, people from different areas cannot understand each other using their local variations so they use a standardized German which no one really speaks at home.

One story — a true one — has it that when John F Kennedy said “Ich bin ein Berliner” in a speech at the Berlin Wall he actually said in the local dialect that he was a jam doughnut. Common German and local are not the same thing at all.

The reason for this is that the language varies from household to household. Every family does have its own little private inside jokes; anyone who has ever met the in-laws knows this.

So too do neighbourhoods, villages and so on. A national language is like a patch-work quilt of these local variations.

To put this into economic terms of our networks, yes, we have that efficiency argument that we should all be using the same inter-changeable language, but that’s just not what we do. There’s a strong force, just us being people, breaking that language up into local variants, as happened with Latin and then Portuguese, Spanish, French, and Italian over the centuries.

February 24, 2018

How to Speak Cockney – Anglophenia Ep 36

Anglophenia

Published on 26 Aug 2015Have a butcher’s at this video with your china plates. Not sure what this means? Learn how to speak Cockney rhyming slang with Anglophenia’s Kate Arnell.

February 17, 2018

QotD: Modern forms of argument

I’m not sure whether this is an example of Argumentum ad anus extractus, which is the logical fallacy of pulling stuff out of your ass, or Argumentum ad feces fabricatum, which is argument by making shit up.

Tamara Keel, “News to me”, View From The Porch, 2016-06-13.

February 5, 2018

A brief history of plural word…s – John McWhorter

TED-Ed

Published on 22 Jul 2013View full lesson here: https://ed.ted.com/lessons/a-brief-history-of-plural-word-s-john-mcwhorter

All it takes is a simple S to make most English words plural. But it hasn’t always worked that way (and there are, of course, exceptions). John McWhorter looks back to the good old days when English was newly split from German — and books, names and eggs were beek, namen and eggru!

Lesson by John McWhorter, animation by Lippy.

QotD: The Age of Hypocrisy

Hitler (one cannot mention him without the subliterates mouthing, “Reductio ad Hitlerum!” — not realizing that they are quoting Leo Strauss) was the great enabler. He gave cover to all lesser evils, including the greater of the lesser ones; and thereby retired all the prattling politicians from the Age of Hypocrisy, which he closed. Now all the baddies seemed good, by comparison, and everyone needed a baddie of his own, or they would get one assigned from Berlin.

The Age of Hypocrisy re-opened, of course, with Hitler’s death, when political discourse again softened. (Hypocrisy is the padding on the madhouse walls.) But for a twelve-year run in Germany, and shorter periods wherever their shadow fell, Hitler’s Nazis erased hypocrisy.

This is what Karl Kraus meant, when he said that the Nazis had left him speechless. For decades he had exposed the lies and deceitful posturing not only of politicians in the German-speaking world, but among their immense supporting cast of journalists and fashion-seeking intellectuals. He was the greater-than-Orwell who strode to the defence of the German language, when it was wickedly abused. He identified the new “smelly little orthodoxies” as they crawled from under the rocks of Western Civ — the squalid, unexamined premisses that led by increments to the slaughterhouse of Total War. He was not, even slightly, a revolutionist; he had no argument against anyone’s wealth or status, even his own. Rather, through savage satirical humour, with language untranslatably precise, impinging constantly upon the poetic, he undressed the false.

He had seen the First World War coming, in the malice spreading through the language; in the smugness that fogged perception; in the lies that people told each other, to preserve their amour-propre; in the jingo that lurked beneath the genteel. After, he saw worse.

David Warren, “The decline of requirements”, Essays in Idleness, 2016-06-07.