The OG internet moguls were legit Mountain Dew-addled asocial coding savant t-shirt slobs, and that style quickly became a way to intimidate tie clad IBMers and VCs in meetings. “Man, these guys must be geniuses, they don’t even GAF”

The schlubby chic look was part of the con. Made him seem like someone who didn’t care about the money, which sends a subtle anti-capitalist, anti-consumerist, anti-finance bro NLP type message.

https://twitter.com/esaagar/status/1603015654206066688Posted by Noam Blum (neontaster) on Thursday, December 15th, 2022 1:25pm

Then it became sort of a cosplay thing for vaporware charlatans targeting FOMO investors.

“psst, Bob, should we really give $20 million to this guy? He’s picking his nose and wiping it on his cargo shorts rn”

“But remember that last nosepicker we passed on? He made $10 billion”

*fun fact: 8 years ago nosepicking guy was a Ralph Lauren-wearing chairman of the Delta Chi party committee, majoring in Entrepreneurship. And then he took the Silicon Valley Dress Down for Success seminar

There are other stylistic variations on pure slovenliness; the Black Turtleneck Next Steve Jobs gambit, and the coffee-clutching Patagonia Vest & Untuckits Next Steve Bezos thing

Oh, and the hoodies, so many hoodies.

For everybody thinking “tech people need to start wearing IBM suits again”: if you showed up to work or a VC meeting in one you would be thought deranged, building security, or a lunch caterer

For me the peak of Silicon Valley style will always be the pre-internet Assembly Language programmer polyester clip-on tie & short sleeve Sears Towncraft dress shirt look. The effortless nonchalance told you “I can trust this person not to run to the Carribean with my money”

David Burge (@Iowahawk), Twitter, 2022-12-15.

January 1, 2025

QotD: The OG internet moguls

December 24, 2024

QotD: The real hero of It’s A Wonderful Life

@BillyJingo

I get the feeling you’re the kind of guy who secretly rooted for Mr Potter.@Iowahawkblog

George Bailey: whines for a public bailout of his grossly mismanaged financial institutionMr Potter: reinvigorates boring small town by developing exciting nightlife district

David Burge (@Iowahawkblog), Twitter, 2022-11-16.

October 28, 2022

The real tech startup lifecycle

Dave Burge (aka @Iowahawk on the Twits) beautifully encapsulates the lifecycle of most successful tech startups:

I like the thing where people assume everybody working at Twitter is a computer science PhD slinging 5000 lines of code daily with stacks of job offers for Silicon Valley headhunters, and not a small army of 27-year old cat lady hall monitors

Successful social media companies begin in a shed with 12 coders, and end up in a sumptuous glass tower with 1200 HR staffers, 2000 product managers, 5000 salespeople, 20 gourmet chefs, and 12 coders

True story, I was in SV a few weeks ago and visited a startup that’s gone from $4MM to $100+MM rev in 2 years. HQ currently cramped office with 30-40 coders in a strip mall, but moving to office tower soon. I’m like, man, you’ll eventually be missing this.

Why do successful tech companies have so many seemingly useless employees? For the same reason recording stars have entourages

Here’s the sociology: 5 coders form startup. Least embarrassing one becomes CEO. The other ones, CFO, COO, CMO, and best coder becomes CTO.

Company gets big; CFO, COO CMO hold a dick measuring contest to hire the biggest dept.

CTO still wants to be the only coder.

I suspect it really does takes 1000 or more developers to keep Twitter running; backend, DB, security, adtech/martech etc. But I’d guess a significant # of Twitter devs are basically translating what triggers the cat ladies into AI algorithms.

July 4, 2019

August 12, 2018

QotD: Journalism

Journalism is about covering important stories. With a pillow, until they stop moving.

David Burge (@iowahawkblog), Twitter, 2013-05-09.

March 6, 2018

Real estate reality may finally be changing minds in Silicon Valley

I’ve never lived in Silicon Valley, and my one vist there was over 25 years ago — but even then, I thought the real estate market was far higher than it should have been. The sale of a tiny house in Sunnyvale (for $2 million or $2,358 per square foot) is symbolic of real estate values all around the area, as the stories get told of new employees living in their cars because even on six-figure salaries, they can’t afford to buy or even rent near where they work. Iowahawk linked to a New York Times article which shows that some movers and shakers acknowledge that Silicon Valley has a serious problem:

Silicon Valley execs devise strategy to solve Silicon Valley affordable housing crisis: GTFO of Silicon Valleyhttps://t.co/MlRDfqJWbD

— David Burge (@iowahawkblog) March 5, 2018

If there was ever an industry that had no reason to be concentrated in one geographic location, it's software tech.

— David Burge (@iowahawkblog) March 5, 2018

In 95% of the American landmass, this is a $75,000 house. (ht @rdmcghee)https://t.co/sv8pwNS0g1

— David Burge (@iowahawkblog) March 5, 2018

I mean, I can kind of understand expensive housing in NY or SF, but Silicon Valley? It has all the excitement of Dubuque, at Monaco prices

— David Burge (@iowahawkblog) March 5, 2018

"I'm only 1 hour from the mountains and beaches!" – Silicon Valley drone coding at 2 AM to pay his $2 million house trailer mortgage

— David Burge (@iowahawkblog) March 5, 2018

December 16, 2017

What? There’s another Star Wars movie? Did the Death Star regenerate itself?

My level of excitement for new Star Wars movies probably peaked just before the release of The Revenge of the Return of the Bride of the Jedi, and now has fallen and can’t get up. I’m perhaps not alone, as David “Iowahawk” Burge kindly illustrates:

Oh great another Star Wars movie so I get to read through another 3 weeks of cartoon character theological debates

— David Burge (@iowahawkblog) December 15, 2017

Spoiler alert: in the new Dawn of the Blasticons, Grabnar Jibbersnorf laser-freezes the Bloongsnoodi, even though his charmcloak DIDN'T HAVE THE POLARIAN CRYSTALS

— David Burge (@iowahawkblog) December 15, 2017

And then they expect us to believe Roobu Gark would let Grabnar and D-60Z tractorpod the carbonzone, without their infinitysocks! I mean like WTF?

— David Burge (@iowahawkblog) December 15, 2017

THEY'RE DESTROYING MY WHOLE CHILDHOOD

— David Burge (@iowahawkblog) December 15, 2017

April 12, 2017

United Airlines implies that the beatings will continue until customer morale improves

One of several videos from other passengers on the flight:

Some reactions from around the net to a United Airlines initiative to treat their customers like unruly prison inmates:

Southwest changes slogan in wake of #United pic.twitter.com/fnNf5NtRo2

— Jordan (@jordansammy) April 11, 2017

The world is rightly abuzz over an awful incident yesterday in which a man was beaten and dragged off a plane by police at Chicago’s O’Hare airport for the crime of wanting to use the seat he’s paid for on a United Airline flight getting ready to leave for Louisville.

The man claimed to be a doctor who had patients to see the next morning, explaining why he neither took an initial offer made to everyone on the plane to accept $400 and a hotel room for the night in exchange for voluntarily giving up his seat nor wanted to obey a straight-up order to leave, in an attempt on United’s part to clear four seats for its own employees on the full flight.

No one considered even the $800 that was offered after everyone had boarded enough for the inconvenience, so United picked four seats and just ordered those in them to vacate. But the one man in question was not interested in obeying. (Buzzfeed reports, based on tweets from other passengers, that the bloodied man did eventually return to the plane.)

While United’s customer service policies in this case are clearly heinous and absurd, let’s not forget to also cast blame on the police officers who actually committed the brutality on United’s behalf. NPR reports that the cops attacking the man “appear to be wearing the uniforms of Chicago aviation police.”

However violent and unreasonable the incident might appear to us mere ignorant peasants, the CEO assures his minions that beatings of this sort are totally within normal procedural guidelines:

The head of United Airlines said in an email to his employees Monday that the security guards who violently dragged a passenger from his seat were following “established procedures for dealing with situations like this,” according to a tweet by CNBC reporter Steve Kopack.

“As you will read, the situation was unfortunately compounded when one of the passengers we politely asked to deplane refused and it became necessary to contact the Chicago Aviation Security Officers to help. Our employees followed established procedures for dealing with situations like this,” wrote Oscar Munoz, CEO of United Airlines.

Munoz’s message to staff comes amid public scrutiny after a passenger refused to relinquish his seat on an overbooked plane and was violently dragged off the plane by three security officers.

Surfaced videos of the incident have since gone viral.

Headline: passenger beaten, abused by United Airlines

Me: how could he tell— David Burge (@iowahawkblog) April 10, 2017

February 2, 2017

November 27, 2014

For our American friends, before the gorging begins…

Charles C. W. Cooke has your go-to guide to political conversations with your family this Thanksgiving:

Your crazy uncle complains in passing that the construction on Redlands Avenue is limiting the flow of traffic to his hardware store, and wonders if the job could be completed more quickly.

This must not be allowed to stand. Ask your uncle if he’s an anarchist and if he has heard of Somalia. If you missed Politics 101 at Oberlin, refer to the Fact Cards that you have printed out from Vox.com and explain patiently that the government is the one thing that we all belong to and that the worry that it is “too big” or “too centralized” or “too slow to achieve basic tasks” has a long association with neo-Confederate causes.

Remind him also that:

- the state has a monopoly on legitimate violence.

- Europe is doing really well.

- The Koch Brothers.

- “Obstruction.”

Should all that fail, insist sadly that if he doesn’t fully apologize for his opinions you will have to conclude that he hates gay people. Ask why your family has to talk about politics all the time.

Update: A related tweet that just has to be shared.

As God is my witness, I thought turkeys could govern.

— David Burge (@iowahawkblog) November 27, 2014

September 13, 2014

Ohio State University’s bureaucratic approach to student-to-student intimacy

US colleges and universities are struggling to come up with new and innovative ways of regulating how their students interact in intimate situations. Ohio State University, for example, now requires that students who engage in sexual relations must agree on why they want to have sex to avoid the risk of sexual assault charges being brought:

At Ohio State University, to avoid being guilty of “sexual assault” or “sexual violence,” you and your partner now apparently have to agree on the reason WHY you are making out or having sex. It’s not enough to agree to DO it, you have to agree on WHY: there has to be agreement “regarding the who, what, where, when, why, and how this sexual activity will take place.”

There used to be a joke that women need a reason to have sex, while men only need a place. Does this policy reflect that juvenile mindset? Such a requirement baffles some women in the real world: a female member of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights told me, “I am still trying to wrap my mind around the idea of any two intimates in the world agreeing as to ‘why.’”

Ohio State’s sexual-assault policy, which effectively turns some welcome touching into “sexual assault,” may be the product of its recent Resolution Agreement with the Office for Civil Rights (where I used to work) to resolve a Title IX complaint over its procedures for handling cases of sexual harassment and assault. That agreement, on page 6, requires the University to “provide consistent definitions of and guidance about the University terms ‘sexual harassment,’ ‘consent,’ ‘sexual violence,’ ‘sexual assault,’ and ‘sexual misconduct.’” It is possible that Ohio State will broaden its already overbroad “sexual assault” definition even further: Some officials at Ohio State, like its Student Wellness Center, advocate defining all sex or “kissing” without “verbal,” “enthusiastic” consent as “sexual assault.”

Ohio State applies an impractical “agreement” requirement to not just sex, but also to a much broader category of “touching” that is sexual (or perhaps romantic?) in nature. First, it states that “sexual assault is any form of non-consensual sexual activity. Sexual assault includes all unwanted sexual acts from intimidation to touching to various forms of penetration and rape.” Then, it states that “Consent is a knowing and voluntary verbal or non-verbal agreement between both parties to participate in each and every sexual act … Conduct will be considered “non-consensual” if no clear consent … is given … Effective consent can be given by words or actions so long as the words or actions create a mutual understanding between both parties regarding the conditions of the sexual activity–ask, ‘do both of us understand and agree regarding the who, what, where, when, why, and how this sexual activity will take place?’”

Update:

Advice to college guys: avoid all college women. If you want to have sex, go to a prostitute and get a receipt. http://t.co/sh9voKuJ9L

— David Burge (@iowahawkblog) September 13, 2014

August 26, 2014

Tax inversions: “Canada, it would seem, is the new Delaware”

In Maclean’s, Jason Kirby looks for reasons why Tim Hortons is interested in a deal with Burger King:

For starters, let’s consider Burger King’s motivation for buying Tim Hortons. It is not looking for synergies. Don’t expect to see Burger King roll out twinned stores, with one counter selling Whoppers, the other Timbits, as per Wendy’s strategy when it owned Tims. Instead, Burger King wants to avoid paying U.S. taxes. If the deal goes ahead (no agreement has been finalized) Burger King will achieve this through what’s known as a “tax inversion.” It would buy Tim Hortons, then declare the newly merged company to be Canadian. And because companies in Canada enjoy a lower corporate tax rate than those in America — 15 per cent in Canada compared to an official U.S. rate of 35 per cent — Burger King’s future tax bills could be a lot smaller.

Canada, it would seem, is the new Delaware.

So Burger King is buying Tim Hortons, but in doing so, the combined Tim Hortons and Burger King will be financially engineered to be Canadian, at least on paper. A statement released by the companies following the Wall Street Journal‘s initial report on the deal said Burger King’s largest shareholder, 3G Capital, a Brazilian private equity firm, would own the majority of the shares of the newly created company. And you can be sure any tax savings will flow back to shareholders in the form of higher dividends.

It’s clear what’s driving Burger King to pursue this deal. But there’s been far less attention paid to the question: what’s in this for Tim Hortons?

According to Tim Hortons, the answer — as it unceasingly has been for the past two decades — is the pursuit of international growth. In the statement from Tim Hortons and Burger King, the companies said the coffee chain will have ”the potential to leverage Burger King’s worldwide footprint and experience in global development to accelerate Tim Hortons growth in international markets.”

Update: Kevin Williamson points out that relatively few US companies actually relocate to other countries now, but that the number is clearly increasing and knee-jerk reactions to that by politicians may well make it worse.

There are trillions of dollars in U.S. corporate earnings parked overseas, and progressives want the government to shove its greedy snout all up in that, denouncing “corporate cash hoarders” and blaming un-repatriated corporate earnings for everything from the weak job market to chronic halitosis. Harebrained schemes for putting that corporate cash in government coffers abound. So the current balance could quite easily be tipped. And after years of ad-hocracy under Barack Obama et al., U.S.-style “rule of law” may not be as attractive as it once was. A few more arbitrary NLRB decisions or political jihads from the IRS could change a few minds about the value of U.S. law and governance.

The question isn’t whether you can bully Walgreens out of its plan to move to Switzerland. The question is whether the next Apple or Pfizer ever puts down legal roots in the United States in the first place. Right now, the friction works in favor of the United States, but there is no reason to believe that that will always be the case. You think that Singapore wouldn’t like to be the world’s banking or pharmaceutical capital? That Seoul lacks ambition? That the Scots who brought us the Enlightenment can’t run a decent system of law and property rights? Burger King is not talking about moving to some steamy banana republic for tax purposes, but to stodgy, stable, predictable, boring old Canada. Boring and predictable looks pretty good if you’re Burger King, especially when the alternative is unpredictable and expensive. Unpredictable and expensive is what you date when you’re young and stupid — you don’t marry it.

Update the second:

Golly, I thought we were supposed to admire people who trek northward over the border seeking a better life for their families. #BurgerKing

— David Burge (@iowahawkblog) August 26, 2014

November 21, 2010

November 15, 2010

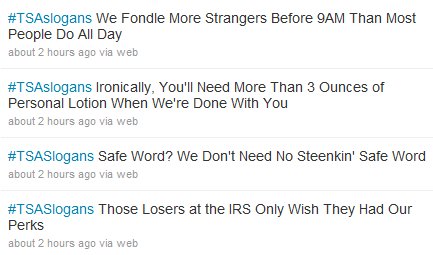

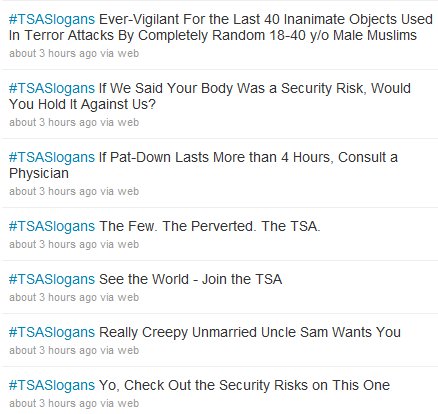

Iowahawk provides some suggested new slogans for the TSA

If you aren’t following Iowahawk on Twitter, you’re missing a lot of funny stuff.

November 25, 2009

Tonight on Iowahawk Geographic

This is a fascinating show on a topic of great public and scientific interest:

Narrator

This is the University of East Anglia in the United Kingdom, home of one of the largest nesting populations of climate scientists in Europe.

Gentle ant’s-eye scene of idyllic campus lawn, strewn about with drunken mating undergraduates

Each year it attracts magnificent migratory flocks of graduate students, adjuncts and visiting faculty from across the northern hemisphere.

Shots of jumbo jets landing at Heathrow; herds of climate researchers busily milling at Duty Free shops, retrieving baggage, phoning for prearranged limo service

Within minutes of arriving on campus, the migratory researchers approach the entrance of the Climate Research Unit and perform the secret credential dance, fiercely displaying their prominent curriculum vitae. This signals to the security drone that they can be trusted with the sacred electronic lanyard badge that will grant them entrance to the hive’s inner sanctum.

During the upcoming research season, this hive alone will produce over 6 million metric tons of grant-sustaining climate data guano, but until recently little was known about the elusive genus of homo scientifica living inside. Where do they come from? What strange force draws them here year after year? In order to unravel the mystery, Iowahawk Geographic documentary filmmaker David Burge undertook a painstaking one-week project to finally capture the climate researchers in their native habitat.