Calum

Published 5 Oct 2022The humble shipping container changed our society — it made International shipping cheaper, economies larger and the world much, much smaller. But what did the shipping container replace, how did it take over shipping and where has our dependance on these simple metal boxes led us?

(more…)

August 2, 2023

How Shipping Containers Took Over the World (then broke it)

July 31, 2023

RSC 1917: France’s WW1 Semiauto Rifle

Forgotten Weapons

Published 17 Nov 2015Did you know that the French Army issued more than 80,000 semiautomatic rifles during WWI? They had been experimenting with a great many semiauto designs before the war, and in 1916 finalized a design for a rotating bolt, long stroke gas piston rifle (with more than few similarities to the M1 Garand, actually) which would see field service beginning in 1917. An improved version was put into production in 1918, but too late to see any significant combat use.

The RSC 1917 was not a perfect design, but it was good enough and the only true semiauto infantry rifle fielded by anyone in significant numbers during the war.

July 29, 2023

French 75mm of 1897

vbbsmyt

Published 30 Dec 2021The French 75 is widely regarded as the first modern artillery piece. It was the first field gun to include a hydro-pneumatic recoil mechanism, which kept the gun’s trail and wheels perfectly still during the firing sequence. Since it did not need to be re-aimed after each shot, the crew could reload and fire as soon as the barrel returned to its resting position. In typical use the French 75 could deliver fifteen rounds per minute on its target, either shrapnel or high-explosive, up to about 8,500 m (5.3 mi) away. Its firing rate could even reach close to 30 rounds per minute, albeit only for a very short time and with a highly experienced crew. [wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Canon_d…]

The concept for the gun anticipated future conflict being a war of manoeuver — with massed infantry and cavalry attacks — based on the experience of the wars of 1870-1872. Consequently the gun was designed to be able to be moved easily, set up quickly and fire antipersonnel shells (shrapnel) rapidly, and without the need to reset the carriage after each shot. Two critical components were the cased ammunition (shell and cartridge as a single unit) and a recoil system that completely absorbed the recoil forces and returned the gun to its original position without disturbing the gun’s position.

This animation shows the actions necessary to prepare the gun from its “travelling” state to operational state. The carriage has to be “locked” into a fixed position and levelled. The operation of shrapnel shells depends upon setting a time fuse to explode the shell just in front of an attacking force, to shower them with balls, and demonstrates the French Débouchoir mechanical fuse setter that allowed time fuses to be set rapidly and accurately. The liquid (oil) and air (pneumatic) recoil mechanism used a “floating piston” — on one side hydraulic oil and on the other compressed air. The design must keep these two separated while allowing the free piston to move rapidly. The French design laid great emphasis on seals made of silver – being soft enough to conform to the sleeve housing, but as reported by the US when they started manufacturing the 75mm, the key element was highly precise machining of the sleeve housing the free piston.

The French 75mm of 1897 was of less use with the introduction of trench warfare, where howitzers and mortars being the primary artillery, but the 75mm retained some value, one use being firing shrapnel shells at aircraft. A longer time fuse had to be developed to reach the altitude that some aircraft flew at.

(more…)

July 24, 2023

Lorenzoni Repeating Flintlock Pistol

Forgotten Weapons

Published 13 Aug 2012Today we have one of the oldest guns we’ve looked at, a Lorenzoni repeating flintlock pistol. The system was designed by an Italian gunmaker in Florence name Michele Lorenzoni. They were made in very small numbers, and the workmanship is stunning, especially considering that they were first manufactured in the 1680s.

Instead of using a revolving cylinder pre-loaded with multiple shots, the Lorenzoni system utilizes powder and ball magazines in the frame of the gun and a rotating breechblock much like a powder throw tool used today for reloading ammunition.

(more…)

July 23, 2023

Tom Whipple’s history of radar development during WW2

In The Critic, Robert Hutton reviews The Battle of the Beams by historian Tom Whipple, who retells the story of the technological struggle between Britain and Germany during the Second World War to find ways to guide RAF or Luftwaffe pilots to their targets:

In an age when my phone can tell me exactly where I am and how to get where I’m going, it’s hard sometimes to imagine a time when navigation was one of any traveller’s great challenges. At the outbreak of the Second World War, the advice to Royal Air Force pilots trying to find their way was, more or less, to look out of the window and see whether anything on the ground looked familiar. The Luftwaffe, though, had a rather more sophisticated means of finding their targets.

As Britain braced herself for the bomber onslaught of 1940, there was comfort in knowing that radar would give Hurricanes and Spitfires advance warning of where the attack was coming. As soon as the sun went down, so did the fighters: at night, relying on their eyeballs, they simply couldn’t find the enemy.

That wasn’t so bad, as long as the German pilots had the same problem, but one young British scientist began to suspect that the Luftwaffe had developed a technology that allowed them to find their way even in the dark, guided by radio beams. In June 1940 he found himself explaining to Winston Churchill that German bombers could accurately reach any spot over England that they wanted, even in darkness.

Reg “RV” Jones was the original boffin: a gifted physicist who was recruited to the Air Ministry at the start of the war to help make sense of intelligence reports that offered clues about enemy technology. It was a role to which he was perfectly suited: a man who liked puzzles, with the ability to absorb lots of information and see links, as well as the arrogance to insist on his conclusions, even when his superiors didn’t like them.

The story of the radio battle has been told before, not least by Jones himself. His 1978 memoir Most Secret War was a bestseller and remains in print. It is 700 pages long, though, and it assumes a lot of knowledge about the way 1940s radios worked that readers probably had 50 years ago. Since few people under 50 have much clue why a radio would need a valve or what you might do with a slide rule, there is definitely room for a fresh telling.

July 20, 2023

Three phases of a cultural cycle

Chris Bray visits an art museum and shares some thoughts provoked by his experiences:

There’s a moment, in a museum supported by a deep permanent collection, when you transition from glowing oil paint depictions of Lord Major Fluffington P. Farnsworth-Hadenwallace, Seventh Earl of Wherever, Ninth Duke of Someotherplace, posing in his lordly estate with a bowl of fruit and his array of status decorations, to the shocking emergence of late-19th century innovations in painting, and you find yourself thinking that huh, this Renoir dude really knew his stuff, like you’re the first person to ever notice.

These explosive moments of creativity were usually social: artists gathering, talking, seeing the work of other artists and thinking about new ways of seeing and showing. Individual acts of artistic liberation appeared in the context of an emerging cultural freedom. Renoir and Monet hung out together.

You can see the tide coming in and going out. You can watch enormous waves of joyful innovation, or — respectful nod to the German Expressionists — anxious and anguished innovation. It’s on the wall: here’s the moment when people experienced unusual freedom of vision. You can see artists pursuing beauty with disciplined attention, in a cultural atmosphere that allows the pursuit.

And it’s just so abundantly clear that something opened in the world, somewhere between 1870 and … 1950? Or so? And then it began to close, and the closure recently began picking up force. There are periods of general creativity and periods of general stultification and retrenchment; there was one Italian Renaissance, one Scottish Enlightenment, and so on. Weimar Germany, sick as it was, fired more brilliant art into the world in twenty years than many cultures produce in a period of centuries, though a certain teenager who lives in my house would like you to know that Fritz Lang sucks and please stop with those boring movies and I’ll be in my room.

So it seems to me that the first part of the cultural cycle is the making phase, the period of astonishing innovation; then comes the consolidation and appreciation, the moment the heirs to sewing machine fortunes show up and notice how good everything is; then comes the phase when a few monk-equivalents try to keep the record of accomplishment alive in the context of a hostile or indifferent culture, while most institutions reject innovation and turn to scolding, wrecking, and cannibalization. The fifth Indiana Jones movie. She-Hulk. Like that. I just spent twenty minutes in a Barnes and Noble, and the “new fiction” section may still be making me feel tired next week.

We’re living through a decline in fertility — in literal fertility, in rates of people being married and making babies and hanging around to raise children — at the moment when cultural fertility also seems to be going into freefall. Your results may vary, but I’m finding the moment manageable, largely with piles of earlier books and the occasional sprint to a place like the Clark. Fecundity and sterility appear in cycles, but you can time travel. You can reach back. Mary McCarthy got me through June, and Willa Cather is helping with July. Evelyn Waugh covered roughly February through May.

If you’re near the Berkshires, a worthwhile Edvard Munch exhibit is around until mid-October.

It’s very strange to be in the river and then to suddenly notice that it isn’t running — you’ve hit a long stretch of dead water, so still it starts to stink. I assume it will pass. But until then …

July 14, 2023

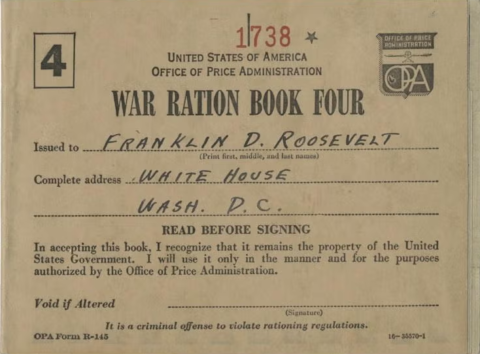

Bread rationing in the United States during WW2

I haven’t studied the numbers, but I strongly suspect that most US government food rationing during the war was effectively theatre to encourage more support of the war effort: except in a very few areas, the US was more than self-sufficient in most foodstuffs. At the Foundation for Economic Education, Lawrence W. Reed recounts one of the least effective government moves in food rationing:

According to an old joke from the socialist and frequently underfed Soviet Union, Stalin goes to a local wheat farm to see how things are going. “We have so many bags of wheat that, if piled on top of each other, they could reach God himself!” the farmer told Comrade Stalin.

“But God does not exist,” the dictator angrily replied. “Exactly!” said the farmer. “And neither does the wheat.” Nobody knows what happened to the farmer, but at least Stalin died in 1953.

Soviet socialism, with its forced collectivism and ubiquitous bread lines, gave wheat a bad name. Indeed, it was lousy at agriculture in general. As journalist Hedrick Smith (author of The Russians) and many other authorities noted at the time, small privately owned plots comprised just three percent of the land but produced anywhere from a quarter to a half of all produce. Collectivized agriculture was a joke.

America is not joke-free when it comes to wheat. We are a country in which sliced bread was both invented and banned, and a country in which growing wheat for your own consumption was ruled to be an act of “interstate commerce” that distant bureaucrats could regulate. No kidding.

On this anniversary — July 7 — of both the birth in 1880 of sliced bread’s inventor and of the day in 1928 that the first sliced bread from his machine was sold, it’s fitting to recall these long-forgotten historical facts.

The Iowa-born jeweler and inventor Otto Rohwedder turned 48 on the very day the first consumer bought the product of his new slicing machine. The bread was advertised as “the greatest forward step in the baking industry since bread was wrapped” and it quickly gave rise to the popular phrase, “the greatest thing since sliced bread.” Before 1928, American housewives cut many a finger by having to slice off every piece of bread from the loaves they baked or bought. Sliced bread was an instant sensation.

Rohwedder earned seven patents for his invention. The original is proudly displayed at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. He likely made a lot more money from the bread slicing machine than he ever did as a jeweler. He died in 1960 at the age of 80.

Enter Claude Wickard, Secretary of Agriculture under Franklin Roosevelt from 1940 to 1945. On January 18, 1943, he banned the sale of sliced bread. Exactly why seems to be in dispute but the most likely rationale was to save wax paper and other resources for war production. He rescinded the ban two months later, explaining then that “the savings are not as much as we expected.”

I’m sure Hitler and Hirohito were relieved.

July 12, 2023

Nazi drone war begins – War Against Humanity 103

World War Two

Published 11 Jul 2023Bombing enemy civilians does nothing to advance a nation’s war effort. But now, Adolf Hitler believes that the V-1 flying bomb, the first of the Vengeance Weapons, will bring London to its knees and unite the German population behind the war effort as never before. The missiles are ready for launch and thousands more civilians will die to satisfy the Führer’s

delusions.

(more…)

July 10, 2023

QotD: Liberal and conservative views on innovation

Liberals and conservatives don’t just vote for different parties — they are different kinds of people. They differ psychologically in ways that are consistent across geography and culture. For example, liberals measure higher on traits like “openness to new experience” and seek out novelty. Conservatives prefer order and predictability. Their attachment to the status quo is an impediment to the re-ordering of society around new technology. Meanwhile, the technologists of Silicon Valley, while suspicious of government regulation, are still some of the most liberal people in the country. Not all liberals are techno-optimists, but virtually all techno-optimists are liberals.

A debate on the merits of change between these two psychological profiles helps guarantee that change benefits society instead of ruining it. Conservatives act as gatekeepers enforcing quality control on the ideas of progressives, ultimately letting in the good ones (like democracy) and keeping out the bad ones (like Marxism). Conservatives have often been wrong in their opposition to good ideas, but the need to win over a critical mass of them ensures that only the best-supported changes are implemented. Curiously, when the change in question is technological rather than social, this debate process is neutered. Instead, we get “inevitablism” — the insistence that opposition to technological change is illegitimate because it will happen regardless of what we want, as if we were captives of history instead of its shapers.

This attitude is all the more bizarre because it hasn’t always been true. When nuclear technology threatened Armageddon, we did what was necessary to limit it to the best of our ability. It may be that AI or automation causes social Armageddon. No one really knows — but if the pessimists are right, will we still have it in us to respond accordingly? It seems like the command of the optimists to lay back and “trust our history” has the upper hand.

Conservative critics of change have often been comically wrong — just like optimists. That’s ultimately not so interesting, because humans can’t predict the future. More interesting have been the times when the predictions of the critics actually came true. The Luddites were skilled artisans who feared that industrial technology would destroy their way of life and replace their high-status craft with factory drudgery. They were right. Twentieth century moralists feared that the automobile would facilitate dating and casual sex. They were right. They erred not in their predictions, but in their belief that the predicted effects were incompatible with a good society. That requires us to have a debate on the merits — about the meaning of the good life.

Nicholas Phillips, “The Fallacy of Techno-Optimism”, Quillette, 2019-06-06.

June 29, 2023

Miller’s Musket Conversion: The Trapdoor We Have At Home

Forgotten Weapons

Published 15 Mar 2023In 1865, brothers William and George Miller of Meriden CT patented a system to convert percussion muskets to use the new rimfire ammunition that was becoming available. Between 1865 and 1867, the local Meridan Manufacturing Company converted 2,000 surplus US Model 1861 muskets (mostly made by Parker & Snow) to the Miller system, using .58 rimfire ammunition. The US military tested one of these conversions in 1867, and found it to suffer from some gas leakage and about a 3% misfire rate. There was no further Army interest, although the New York and Maryland state militias did both purchase small numbers of the guns.

(more…)

June 23, 2023

FG-42: Perhaps the Most Impressive WW2 Shoulder Rifle

Forgotten Weapons

Published 8 Mar 2023The first production version of the FG42 used a fantastically complex milled receiver and a distinctive sharply swept-back pistol grip. A contract to make 5,000 of them was awarded to Krieghoff in late spring of 1943, but by the fall its replacement was already well into development. The milled receiver used a lot of high-nickel steel which was becoming difficult for Germany to acquire, and it was decided to develop a stamped receiver to ease production obstacles. Ultimately only about 2,000 of the early Type E FG42 rifles were actually made, and only 12 or 15 are registered in the US. They are a remarkably advanced rifle, and extremely interesting.

(more…)

June 17, 2023

Webley-Fosbery Automatic Revolver

Forgotten Weapons

Published 9 Jun 2013This is an update to our previous video on the Webley-Fosbery, which was taken on a low-res camera in a dark room — hopefully this will be a big improvement!

The Webley-Fosbery was an early automatic handgun based on a revolver design. The top half of the frame slides back under recoil, recocking the hammer and indexing to the next round in the cylinder. They were made commercially in both .38 and .455 calibers, with the .455 version attracting interest from British Army officers into World War I.

June 11, 2023

Rewriting the well-worn story of how the steam engine was invented

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes pushes back against the story we’ve been telling for over 200 years about how the steam engine came to be:

The standard pre-history of the steam engine goes a little like this:

- There were a few basic steam-using devices designed by the ancients, like Hero of Alexandria’s spinning aeolipile, which are often regarded as essentially toys.

- Fast forward to the 1640s and Evangelista Torricelli, one of Galileo’s disciples, demonstrates that vacuums are possible and the atmosphere has a weight.

- The city leader of Magdeburg, Otto von Guericke, c.1650 creates vacuums using a mechanical air pump, and is soon using atmospheric pressure to lift extraordinary weights. This sets off a spate of experimentation by the likes of Robert Boyle, Robert Hooke, Christiaan Huygens, and Denis Papin, to create vacuums under pistons.

- As a result of the new science of vacuums, by the 1690s and 1700s the mysterious Thomas Savery and especially the Devon-based ironmonger Thomas Newcomen are able to develop the first commercially practical engines using atmospheric pressure. Steam engine development continued from there.

This is the narrative that had become set in the 1820s, if not earlier, and has been repeated with many of the same names and dates by book after book after book ever since. It’s a narrative that I have even repeated myself.

But, as I only recently discovered, atmospheric pressure and vacuums were actually being exploited long before Torricelli was even born, by people who believed that vacuums were impossible and had no concept of atmospheric pressure. Devices very much like Savery’s, which exploited both the pushing force of expanding hot steam and the sucking effect of condensing it with cold — what we now know to be caused by atmospheric pressure — were being developed far earlier.

I began to give a more accurate account of the development of the atmospheric engine in a detailed three-part series on why the steam engine wasn’t invented earlier (see parts I, II, III, which give more detail and the references). But I haven’t put it all together in one easily digestible place, and since writing I’ve continued to discover even more. So here’s a rough sketch summarising what really happened, based on everything I’ve found so far […]

The development of the atmospheric engine was thus significantly longer and more complicated than the traditional narrative suggests. Far from being an invention that appeared from out of the blue, unlocked by the latest scientific advancements, it started to take shape from decades and centuries of experiments and marginal improvements from a whole host of inventors, active in many different countries. It’s a pattern that I’ve seen again and again and again: if an invention appears to be from out of the blue, chances are that you just haven’t seen the full story. Progress does not come in leaps. It is the product of dozens or even hundreds of accumulated, marginal steps.

June 7, 2023

A Harbour goes to France – Mulberry Harbours – Normandy Landings

British Army Documentaries

Published 24 Jun 2020Mulberry harbours were temporary portable harbours developed by the United Kingdom during the Second World War to facilitate the rapid offloading of cargo onto beaches during the Allied invasion of Normandy in June 1944. After the Allies successfully held beachheads following D-Day, two prefabricated harbours were taken in sections across the English Channel from UK with the invading army and assembled off Omaha Beach (Mulberry “A”) and Gold Beach (Mulberry “B”).

(more…)

May 31, 2023

Alvin Toffler may have been utterly wrong in Future Shock, but I suspect his huge royalty cheques helped soften the pain

Ted Gioia on the huge bestseller by Alvin Toffler that got its predictions backwards:

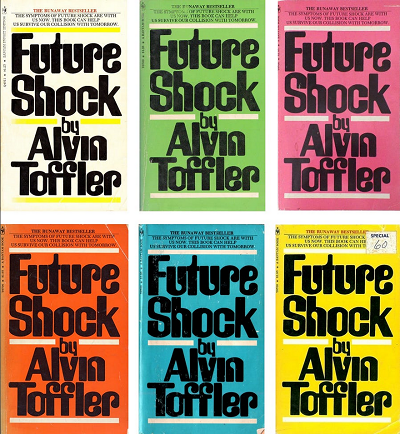

Back in 1970, Alvin Toffler predicted the future. It was a disturbing forecast, and everybody paid attention.

People saw his book Future Shock everywhere. I was just a freshman in high school, but even I bought a copy (the purple version). And clearly I wasn’t alone — Clark Drugstore in my hometown had them piled high in the front of the store.

The book sold at least six million copies and maybe a lot more (Toffler’s website claims 15 million). It was reviewed, translated, and discussed endlessly. Future Shock turned Toffler — previously a freelance writer with an English degree from NYU — into a tech guru applauded by a devoted global audience.

Toffler showed up on the couch next to Johnny Carson on The Tonight Show. Other talk show hosts (Dick Cavett, Mike Douglas, etc.) invited him to their couches too. CBS featured Toffler alongside Arthur C. Clarke and Buckminster Fuller as trusted guides to the future. Playboy magazine gave him a thousand dollar award just for being so smart.

Toffler parlayed this pop culture stardom into a wide range of follow-up projects and businesses, from consulting to professorships. When he died in 2016, at age 87, obituaries praised Alvin Toffler as “the most influential futurist of the 20th century”.

But did he deserve this notoriety and praise?

Future Shock is a 500 page book, but the premise is simple: Things are changing too damn fast.

Toffler opens an early chapter by telling the story of Ricky Gallant, a youngster in Eastern Canada who died of old age at just eleven. He was only a kid, but already suffered from “senility, hardened arteries, baldness, slack, and wrinkled skin. In effect, Ricky was an old man when he died.”

Toffler didn’t actually say that this was going to happen to all of us. But I’m sure more than a few readers of Future Shock ran to the mirror, trying to assess the tech-driven damage in their own faces.

“The future invades our lives”, he claims on page one. Our bodies and minds can’t cope with this. Future shock is a “real sickness”, he insists. “It is the disease of change.”

As if to prove this, Toffler’s publisher released the paperback edition of Future Shock with six different covers — each one a different color. The concept was brilliant. Not only did Future Shock say that things were constantly changing, but every time you saw somebody reading it, the book itself had changed.

Of course, if you really believed Future Shock was a disease, why would you aggravate it with a stunt like this? But nobody asked questions like that. Maybe they were too busy looking in the mirror for “baldness, slack, and wrinkled skin”.

Toffler worried about all kinds of change, but technological change was the main focus of his musings. When the New York Times reviewed his book, it announced in the opening sentence that “Technology is both hero and villain of Future Shock“.

During his brief stint at Fortune magazine, Toffler often wrote about tech, and warned about “information overload”. The implication was that human beings are a kind of data storage medium — and they’re running out of disk space.