The Tank Museum

Published 10 Feb 2023Historian Stuart Wheeler is back with another Anti-Tank Chat. In this episode, he looks at the development and use of improvised, thrown and placed infantry anti-tank weapons, available to British and Commonwealth forces in World War II.

(more…)

May 31, 2023

Improvised Weapons of WW2 | Anti-Tank Chats #8 | The Tank Museum

May 27, 2023

QotD: The war elephant’s primary weapon was psychological, not physical

The Battle of the Hydaspes (326 BC), which I’ve discussed here is instructive. Porus’ army deployed elephants against Alexander’s infantry – what is useful to note here is that Alexander’s high quality infantry has minimal experience fighting elephants and no special tactics for them. Alexander’s troops remained in close formation (in the Macedonian sarissa phalanx, with supporting light troops) and advanced into the elephant charge (Arr. Anab. 5.17.3) – this is, as we’ll see next time, hardly the right way to fight elephants. And yet – the Macedonian phalanx holds together and triumphs, eventually driving the elephants back into Porus’ infantry (Arr. Anab. 5.17.6-7).

So it is possible – even without special anti-elephant weapons or tactics – for very high quality infantry (and we should be clear about this: Alexander’s phalanx was as battle hardened as troops come) to resist the charge of elephants. Nevertheless, the terror element of the onrush of elephants must be stressed: if being charged by a horse is scary, being charged by a 9ft tall, 4-ton war beast must be truly terrifying.

Yet – in the Mediterranean at least – stories of elephants smashing infantry lines through the pure terror of their onset are actually rare. This point is often obscured by modern treatments of some of the key Romans vs. Elephants battles (Heraclea, Bagradas, etc), which often describe elephants crashing through Roman lines when, in fact, the ancient sources offer a somewhat more careful picture. It also tends to get lost on video-games where the key use of elephants is to rout enemy units through some “terror” ability (as in Rome II: Total War) or to actually massacre the entire force (as in Age of Empires).

At Bagradas (255 B.C. – a rare Carthaginian victory on land in the First Punic War), for instance, Polybius (Plb. 1.34) is clear that the onset of the elephants does not break the Roman lines – if for no other reason than the Romans were ordered quite deep (read: the usual triple Roman infantry line). Instead, the elephants disorder the Roman line. In the spaces between the elephants, the Romans slipped through, but encountered a Carthaginian phalanx still in good order advancing a safe distance behind the elephants and were cut down by the infantry, while those caught in front of the elephants were encircled and routed by the Carthaginian cavalry. What the elephants accomplished was throwing out the Roman fighting formation, leaving the Roman infantry confused and vulnerable to the other arms of the Carthaginian army.

So the value of elephants is less in the shock of their charge as in the disorder that they promote among infantry. As we’ve discussed elsewhere, heavy infantry rely on dense formations to be effective. Elephants, as a weapon-system, break up that formation, forcing infantry to scatter out of the way or separating supporting units, thus rendering the infantry vulnerable. The charge of elephants doesn’t wipe out the infantry, but it renders them vulnerable to other forces – supporting infantry, cavalry – which do.

Elephants could also be used as area denial weapons. One reading of the (admittedly somewhat poor) evidence suggests that this is how Pyrrhus of Epirus used his elephants – to great effect – against the Romans. It is sometimes argued that Pyrrhus essentially created an “articulated phalanx” using lighter infantry and elephants to cover gaps – effectively joints – in his main heavy pike phalanx line. This allowed his phalanx – normally a relatively inflexible formation – to pivot.

This area denial effect was far stronger with cavalry because of how elephants interact with horses. Horses in general – especially horses unfamiliar with elephants – are terrified of the creatures and will generally refuse to go near them. Thus at Ipsus (301 B.C.; Plut. Demetrius 29.3), Demetrius’ Macedonian cavalry is cut off from the battle by Seleucus’ elephants, essentially walled off by the refusal of the horses to advance. This effect can resolved for horses familiarized with elephants prior to battle (something Caesar did prior to the Battle of Thapsus, 46 B.C.), but the concern seems never to totally go away. I don’t think I fully endorse Peter Connolly’s judgment in Greece and Rome At War (1981) that Hellenistic armies (read: post-Alexander armies) used elephants “almost exclusively” for this purpose (elephants often seem positioned against infantry in Hellenistic battle orders), but spoiling enemy cavalry attacks this way was a core use of elephants, if not the primary one.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: War Elephants, Part I: Battle Pachyderms”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2019-07-26.

May 25, 2023

The Hoplite Heresy: Why We Don’t Know How the Ancient Greeks Waged War

The Historian’s Craft

Published 9 Feb 2023Hoplites are probably one of the first things that come to mind when one thinks of “Ancient Greece”. Equipped with a bronze spear and wearing bronze armor or a linothorax, and hefting the aspis — the hoplite‘s bronze shield — they fought in phalanxes. The classic mode of fighting in this formation was the “othismos“, the push, with the aim being to disrupt the enemy phalanx and break their formation. But, over the past few decades, views on hoplite warfare have been called into question and seriously revised, because there are problems in the source material. So, what are these problems, and how do historians of Ancient Greece understand hoplite warfare?

May 9, 2023

QotD: Changing German Panzer tactics in 1943

Report of the Commanding General of the 17th Armored Division, 24 April, 1943

The following report, though obviously written in haste with little regard for elegance of expression, gives a good view of the changes in tank tactics which took place on the Eastern Front. This translation was made from a typed copy of the original and thus bears no signature. Nonetheless, there is good reason to believe that the author was the famous Fridolin von Senger und Etterlin, who commanded the 17th Armored Division at this time.

1. The tank tactics which led to the great successes of the years 1939, 1940, and 1941 must now be considered obsolete. Even if it were possible today to breakthrough an antitank front by means of the massive employment of concentrated waves of tanks, we would not be able to make use of these methods, which would once more lead to considerable losses, because of our [tank] production situation. These methods, often employed in rapid succession, would lead to such a quick reduction in tank strength that the character of an armored division would be fundamentally altered. This would lead to difficulties for the higher leadership.

The change in tank tactics is logical. The beginning successes of the weapon, the shock effect of which rested upon the technical achievement and overwhelming invincibility of the attacker, found at last its end in the development of appropriate defenses. From the point of view of production, the building of tanks could not keep pace with the building of antitank weapons. Apparently, a thousand antitank rifles, or dozens of antitank guns, can roll off the production lines for every tank.

The following are drawn from these insights.

2. The new tank tactics, which have already gained inevitable acceptance in the divisions, are outlined below.

The tank group no longer forms the nucleus of the armored division, about which other weapons are grouped as auxiliaries. The tank is a new arm acting in concert with and equal to the old arms. In cooperation with other weapons, it retains its power, even though its numbers are far below those called for by tables of organization.

Its meaning as a new arm is a function of the fact that it combines in itself a goodly portion of the two elements important to the attack: fire and maneuver. It derives these qualities from the fact that it is invulnerable, or less vulnerable, because of its armor.

Because the tank arm combines in itself firepower and mobility to a greater degree than other arms, it is the appropriate weapon for forming the main effort [Schwerpunkt].

The combat of the armored division is characterized by the fact that it is a mobile unit in all its parts and, as a result, the division commander is in a position, in the course of a battle, to chose and form a main effort [Schwerpunkt]. This principle excludes an irrevocable commitment of the tank group before an attack. Rigid employment within the framework of an already established battle plan is replaced by division commander himself holding [the tank group] in readiness and the flexibly employing it in the course of fighting against the required, or known to be appropriate, position.

The battle will begin with the infantry attack. The infantry attack provides the required foundation for the strength of the antitank front, for its length and depth. If the antitank front is known, then the tank attack can be ordered according to the classical principles for leading mobile units against the flanks or, if possible the rear, of an enemy defensive position. This attack should only be carried out exclusively by tanks when they can gain complete surprise. If surprise cannot be gained, then in this flank attack fire superiority must be fought for through the employment of artillery and, for the time being and to a certain extent the fire of the tanks themselves, until the enemy antitank front can be shaken or at least split up. If surprise can be gained, then a break-in against the flank of an antitank front can succeed without preparatory fire.

The attack against an enemy antitank front by means of a successful move against its flanks and rear cannot be carried out by tanks alone. It requires the support of artillery. In our experience, however, tank attacks carried out against the flanks and rear have outrun the artillery groups in direct support. Shifting fires by means of forward observers alone is not enough to ensure the shooting up of defensive fronts. What is needed here is thus the self-propelled batteries, which in the same manner as tanks themselves can quickly change their firing positions and thus attain the same mobility as the tank groups.

3. Now that these principles of the new tactics have been laid out, their use in practice will be explained.

a. The use of tanks as the first attack wave against a strongly fortified, deeply organized defensive position leads always to great losses and is thus false.

b. The use of tanks against deeply organized antitank positions is possible with the stipulation that it be commanded by an all-arms leader in close cooperation with other weapons after the formation of a main effort on the spot and that the further prosecution of the battle be steered by the same all-arms leader.

c. The employment of tanks leads to the greatest success when, sent into action and controlled by the all-arms leader, when they are used to strike the enemy in the flank, soon after the latter has begun an attack and before his antitank weapons have established firm antitank positions. Also in this last case, the attack must, with a view to direction and timing, be ordered by the all-arms leader on the spot. (With this last method the weak forces of the worn out 17th Armored Division annihilated one enemy division at Kuteinikowskaja on the 5th of January 1943 and another at Talowaja on the 27th of January, 1943.)

4. These new tactics are based upon the cooperation of the three main arms (infantry, tanks, and artillery) during the entire course of a battle. This cooperation can only be assured when the leader, that is to say, in all cases where the mass of the division is employed, the division commander himself, controls the cooperation of the arms on the spot throughout the entire battle. If, under the press of circumstance, as generally was the case during the battles between the Don and the Volga, widely separated battle groups [Kampfgruppen] of infantry, tanks and artillery had to be formed, it is essential that each of these battle groups be commanded by an all-arms leader, who is neither the commander of the tank element nor the infantry element of the battlegroup.

The all-arms leader’s means of command is the 10-watt radio built into a tank. With this equipment the leader is connected with the tank leaders as well as the leader of the infantry group, who, in case the proper radios are lacking, is provided with a tank. The all-arms commander is also in contact, by means of his armored personnel carrier, with battlegroups not forming part of the main effort and with his first general staff officer (Ia) working far to the rear.

The leader of the artillery group locates himself, according to the ordinary rules of command and control, with the all-arms leader. He is able, as was explained above, to give effective support only as the leader of an artillery group made up of self-propelled batteries. If he does not have access to some of these, there is always the danger the leader of the tank group would find his mobility limited by being bound to the less mobile towed artillery supporting him.

The place of the leader in combat is far forward, so that he can easily see the tank combat and, on the basis of these observations, can steer the course of the battle. He is sufficiently separated from the forward wave of tanks that he does not get involved in the tank-versus-tank and tank-versus-antitank battles, for this combat will focus his attention on the tanks fighting in the forward lines, to the point where tactical decisions which derive from the cooperation of all arms, can no longer be made.

The place of the leader can, however, rarely be chosen outside of the zone of enemy artillery fire. He can nevertheless remain mobile, thanks to the peculiar virtues of his means of command, namely voice radio. In the course of an attack in progress, he should be far enough forward to allow contact with the infantry group. Through it he can exert the leadership of a combined arms combat.

an armored personnel carrier used as a mobile command post in Russia in 1941From his location the leader should be in a position to himself assemble, according to the development of the situation and the requirements of the cooperation of arms, discrete tank groups.

Cooperation between discrete tank groups and infantry groups is possible if the all-arms leader remains in voice radio contact with the tank group in question. The attachment of tank groups to infantry groups is, as a matter of principle, always to be avoided. The infantry is not in a position to ensure the cooperation of infantry, heavy infantry weapons, and artillery as well as tanks because it is fully occupied with the conduct of the combat of other weapons. On this basis, the attachment of tanks to infantry divisions, which cannot be trained in the cooperation of the three arms, is, as a matter of principle, to be avoided.

The requirement to achieve success by the cooperation of all three arms does not exclude the concentration of all tanks in a single attack. This is still to be striven for. The concentration of tank power in the main effort [Schwerpunkt] will, however, not to striven for through systematic employment on the basis of an established plan, but rather in the course of the battle through the assembling of certain tank groups, in short, through the flexible combat leadership and formation of the main effort [Schwerpunkt] in the course of the battle through the all-arms leader himself.

This battle method, which aims at the close cooperation of the three main arms, cannot function without the formation of a special infantry group mounted in armored personnel carriers. Because it is essentially different, this group does not belong with the wheeled-vehicle mounted infantry of the division. They form, rather, an integrated part of the tank group. They can be attached to the later or will be employed according to the decision of the all-arms leader in accordance with the same principles that apply to the employment of tank waves.

The armored personnel carrier group of the infantry which is attached to the tank group corresponds closely to the self-propelled artillery. Both are special branches of their main arm, which work within the tank group itself and without which the cooperation of the tank group with the mass of the truck-mounted infantry and the towed artillery would not be possible.

5. The following deductions for the construction of tanks can be drawn from the aforementioned portrayal of the tactics and command techniques of the armored division. Because the race between tanks and anti-tank defenses can only be won by even heavier types and thus can not be guaranteed, the focus of effort [Schwerpunkt] in construction must be towards mobility and firepower.

The cooperation of arms can never be so close that artillery-infantry attacks alone can prepare an antitank front so that the tank attack can break through it in a rapid rollover. Instead, tanks must be an a position to use long-range fire to put anti-tank fronts out of action or at least so suppress them so as to make possible the further prosecution of the attack. They are only in a position to do this when they possess weapons of such a caliber that they can win superiority over immobile antitank weapons by means of fire and mobility.

According to this line of reasoning, great things can be expected from the creation of self-propelled artillery batteries. As unarmored fire units with greater range than tanks themselves they are in a position to attain that fire superiority which is necessary to gain the upper hand against the antitank defense.

During this winter’s fighting the best results were gained from assault gun battalions which, because of their great mobility and firepower, were employed and led in the same way as tanks. From the point of view of mobility, they outdid the tanks. Self- propelled guns were likewise successfully employed according to the same principles, to augment tank and assault gun groups, particularly by fire.

In contrast, the Tiger tanks, which were supposed to have fulfilled all three requirements, namely firepower, mobility, and heavy armor, were less successful, for their mobility was not sufficient for the elastic battle leadership outlined above. (In this experience it is important to take into account that the units sent fresh into battle were not at the height of their powers, especially where the use of radio was concerned. The impression of their lack of mobility, especially in rolling country with hard-frozen ground, however, would have been the same, even if the training of the personnel had been completed.)

These lessons of the more and more similar tactics of tanks, assault guns, and self-propelled artillery, which in more or less ad hoc arrangements establish the principle of fast-moving heavy firepower, causes one to wish that these weapons could be organized under a single leader with the goal of combining under him standardized training and well-schooled cooperation. This commander is the commander of the division’s tank group, that is to say, all more or less armored weapons mounted on tracked vehicles that are used for the fire battle. He must also have attached as an essential part an infantry group mounted in armored personnel carriers which should be made available according to a ratio of at least one infantry company for each three tank companies of whatever type.

The self-propelled artillery battalion should not be made an organic part of the tank group because of artillery training and the proposed design that will allow the guns to be dismounted. It should remain an organic part of the artillery regiment and be as- signed, on a case by case basis, to the commander of the tank group.

Unsigned report, probably authored by Fridolin von Senger und Etterlin, who commanded 17th Panzer Division at that time, via Bruce Gudmundsson’s Tactical Notebook, 2023-02-06.

April 29, 2023

What Was the Deadliest Day of the First World War?

The Great War

Published 28 Apr 2023What was the deadliest day of any nation in WW1? There are multiple candidates for that, but why should we even care? Well, the answer to this question highlights a challenge with popular memory that is often focused on the biggest battles of the war like the Somme or Verdun.

(more…)

April 21, 2023

Type 94 Japanese 37mm Antitank Gun on Guadalcanal

Forgotten Weapons

Published 30 Dec 2022The Type 94 was the standard infantry antitank gun of the Japanese Army during World Ware Two. It was developed in the early 1930s as tensions with the Soviet Union rose; there had not been much need for Japanese antitank weapons in China. However, high explosive ammunition was also made for the gun, and it was used in an infantry support role with HE in China as well as in the Pacific.

The Type 94 was small and light, and could be disassembled for transportation without vehicles — a very useful capability on islands like Guadalcanal. Against US M3 Stuart light tanks, the Type 94 was a reasonably potent weapon.

Note that the Japanese also had a Type 94 tank gun, which was not the same as this — and did not use the same 37mm cartridge.

(more…)

QotD: In ancient Greek armies, soldiers were classified by the shields they carried

Plutarch reports this Spartan saying (trans. Bernadotte Perrin):

When someone asked why they visited disgrace upon those among them who lost their shields, but did not do the same thing to those who lost their helmets or their breastplates, he said, “Because these they put on for their own sake, but the shield for the common good of the whole line.” (Plut. Mor. 220A)

This relates to how hoplites generally – not merely Spartans – fought in the phalanx. Plutarch, writing at a distance (long after hoplite warfare had stopped being a regular reality of Greek life), seems unaware that he is representing as distinctly Spartan something that was common to most Greek poleis (indeed, harsh punishments for tossing aside a shield in battle seemed to have existed in every Greek polis).

When pulled into a tight formation, each hoplite‘s shield overlapped, protecting not only his own body, but also blocking off the potentially vulnerable right-hand side of the man to his left. A hoplite‘s armor protected only himself. That’s not to say it wasn’t important! Hoplites wore quite heavy armor for the time-period; the typical late-fifth/fourth century kit included a bronze helmet and the linothorax, a laminated, layered textile defense that was relatively inexpensive, but fairly heavy and quite robust. Wealthier hoplites might enhance this defense by substituting a bronze breastplate for the linothorax, or by adding bronze greaves (essentially a shin-and-lower-leg-guard); ankle and arm protections were rarer, but not unknown.

But the shield – without the shield one could not be a hoplite. The Greeks generally classified soldiers by the shield they carried, in fact. Light troops were called peltasts because they carried the pelta – a smaller, circular shield with a cutout that was much lighter and cheaper. Later medium-infantry were thureophoroi because they carried the thureos, a shield design copied from the Gauls. But the highest-status infantrymen were the hoplites, called such because the singular hoplon (ὅπλον) could be used to mean the aspis (while the plural hopla (ὁπλά) meant all of the hoplite‘s equipment, a complete set).

(Sidenote: this doesn’t stop in the Hellenistic period. In addition to the thureophoroi, who are a Hellenistic troop-type, we also have Macedonian soldiers classified as chalkaspides (“bronze-shields” – they seem to be the standard sarissa pike-infantry) or argyraspides (“silver-shields”, an elite guard derived from Alexander’s hypaspides, which again note – means “aspis-bearers”!), chrysaspides (“gold-shields”, a little-known elite unit in the Seleucid army c. 166) and the poorly understood leukaspides (“white-shields”) of the Antigonid army. All of the –aspides seem to have carried the Macedonian-style aspis with the extra satchel-style neck-strap, the ochane)

(Second aside: it is also possible to overstate the degree to which the aspis was tied to the hoplite‘s formation. I remain convinced, given the shape and weight of the shield, that it was designed for the phalanx, but like many pieces of military equipment, the aspis was versatile. It was far from an ideal shield for solo combat, but it would serve fairly well, and we know it was used that way some of the time.)

Bret Devereaux, “New Acquisitions: Hoplite-Style Disease Control”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2020-03-17.

April 19, 2023

The USMC finds a new mission after WW1

Another excerpt from John Sayen’s Battalion: An Organizational Study of United States Infantry (unpublished, but serialized on Bruce Gudmundsson’s Tactical Notebook:

The 1919 demobilization was nearly as traumatic for the Marines as it was for the Army. Their numbers fell from a peak of 75,000 to about 1,000 officers and 16,000 enlisted in 1920. Authorized strength was 17,400. The 15 Marine regiments and at least three, probably four, machinegun battalions existing at the end of November 1918 had withered away to only five regiments and a couple of separate battalions (one artillery and one infantry) by the following August.

Marine commitments, however, remained heavy. The brigades in both Haiti and the Dominican Republic had their hands full suppressing new rebellions. Guard detachments were still needed for Navy bases and Navy ships. The number of men required for the latter duty had fallen by only 10% since 1918. The Marines also had to staff their own bases at Quantico, Parris Island, and San Diego and they had to find men to rebuild the advance base force as well. When these facts were brought to the attention of Congress in 1920 the latter increased the Marine Corps’ authorized strength to 1,093 officers and 27,400 enlisted but then approved funding for only 20,000.

[…]

The bulk of the Corps’ operating forces were still engaged in colonial police work in the Caribbean. However, the new Commandant, Major General John A. Lejeune, was prescient enough to realize that this would not last and that a much more permanent mission would be needed to secure his service’s future. Instead, Lejeune and his advisors concluded that the real mission of the Marine Corps was “readiness”. While this concept might seem trite, one should consider that the United States was and is primarily an insular power. Its standing army in 1920 served primarily as a garrison force and cadre for a much larger wartime citizen army. Little or none of it would be available for immediate use upon the outbreak of a major war beyond the troops already deployed to major US overseas possessions like the Philippines, Hawaii, or the Panama Canal.

Although the Army of 1920 seemed to have little idea about who its future adversaries were likely to be, the Navy had already fingered Japan as its most likely future opponent. Japan had the most powerful navy after the United States and Great Britain and Japanese-American animosity was growing. The Japanese resented the treatment of Japanese immigrants in California. Americans resented Japan’s high handed actions in China. The Japanese saw American criticism of Japan’s China policy as interference in Japan’s rightful sphere of influence. Any war fought against Japan would be primarily naval in character. However, post war disarmament treaties forbade improvements to any American fortresses west of Hawaii. The League of Nations had also mandated most of the central Pacific islands to Japanese control.

If it was to successfully engage the Japanese fleet, or to threaten Japan itself, the United States Navy would need bases in those central Pacific islands. Hawaii was too far away to be useful and the Philippines were too vulnerable to Japanese attack. Only an expeditionary force could seize and hold the central Pacific islands that the Navy needed and that expeditionary force would have to be ready to move whenever and wherever the Navy did. By staying “ready”, requiring only limited reserve augmentation and, being already under the Navy’s control, the Marine Corps would be much better positioned than the Army to provide this expeditionary force, at least during the critical early stages of the next war.*

* Heinl op cit pp. 253-254; Moskin op cit pp. 219-222; and Clifford op cit pp. 25-29 and 61-64.

April 10, 2023

US Army and Marine Corps deployments other than with the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF)

Another excerpt from John Sayen’s Battalion: An Organizational Study of United States Infantry currently being serialized on Bruce Gudmundsson’s Tactical Notebook shows where US infantry units (US Army and USMC) were deployed aside from those assigned to Pershing’s AEF on the Western Front in France:

Apart from the war in Europe, the principal military concern of the Wilson administration during 1917-18 was the protection of resources and installations considered vital to the war effort. The threat of German sabotage in the United States was taken very seriously. In addition, Mexico was still unstable politically and sporadic border clashes continued to occur into 1919. Mexican oil was also regarded as an essential resource and the troops stationed on the Mexican border were prepared to invade in order to keep it flowing. However, all the National Guard, National Army, and even the Regular Army regiments raised for wartime only were reserved for duty with the AEF. (The National Army 332nd and 339th Regiments did deploy to Italy and North Russia, respectively, but both remained under AEF command.) This left non-AEF assignments in the hands of the pre-war Regular Army regiments.

Out of 38 Regular infantry regiments available in 1917, 25 were on guard duty within the Continental United States or on the Mexican border and 13 garrisoned U.S. possessions overseas. Local defense forces raised in Hawaii and the Philippines eventually freed the pre-war regiments stationed in those places for duty elsewhere. By the end of the war the 15th Infantry in China, the 33rd and 65th (Puerto Rican) Infantry in the Canal Zone, and the 27th and 31st Infantry (both under the AEF tables) in Siberia were the only non-AEF regiments still overseas. Inside the United States state militia (non-National Guard) units and 48 newly raised battalions of “United States Guards” (recruited from men physically disqualified for overseas service) had freed 20 regiments from stateside guard duties, but not in time for any of them to fight in France.

Only twelve pre-war regiments actually saw combat in the AEF. Nine of them served with the early-arriving 1st, 2nd, and 3rd AEF Divisions. The other three were with the late arriving 5th and 7th Divisions. One more reached France with the 8th Division, but only days ahead of the Armistice. By this time, the Regular Army regiments had long ago been stripped of most of their pre-war men to provide cadre for new units. They were refilled with so many draftees that their makeup scarcely differed from those of the National Army.*

The situation with the Marines was similar to that of the Regular Army. Most Marine regiments had to perform security and colonial policing duties that kept them away from the “real” war in France. Also like the Army, the Marines made Herculean efforts to accommodate a flood of recruits, acquiring training bases at Quantico Virginia and Parris Island South Carolina, as their existing facilities became too crowded. The Second Regiment (First Provisional Brigade) continued to police Haiti while the Third and Fourth Regiments (Second Provisional Brigade) did the same for the Dominican Republic. The First Regiment remained at Philadelphia as the core of the Advance Base Force (ABF) but its role soon became little more than that of a caretaker of ABF equipment.

Although there was little danger from the German High Seas Fleet ABF units might still be needed in the Caribbean to help secure the Panama Canal and a few other critical points against potential attacks by German surface raiders or heavily armed “U-cruisers.” Political unrest was endangering both the Cuban sugar crop and Mexican oil. To address such concerns, the Marines raised the Seventh, Eighth, and Ninth Regiments as infantry units in August, October, and November 1917, respectively. The Seventh, with eight companies went to Guantanamo, Cuba, to protect American sugar interests. The Ninth Regiment (nine companies) and the headquarters of the Third Provisional Brigade followed. The Eighth Regiment with 10 companies, meanwhile, went to Fort Crockett near Galveston, Texas to be available to seize the Mexican oil fields with an amphibious landing, should the situation in Mexico get out of hand.

Three other rifle companies (possibly the ones missing from the Seventh and Ninth Regiments) occupied the Virgin Islands against possible raids by German submarines. In August 1918, the Seventh and Ninth Regiments expanded to 10 companies each. The situation in Cuba having subsided, the Marine garrison there was reduced to just the Seventh Regiment. The Ninth Regiment and the Third Brigade headquarters joined the Eighth at Fort Crockett.**

* Order of Battle of the United States Land Forces in the World War op cit pp. 310-314 and 1372-1379. A battalion of United States Guards was allowed 31 officers and 600 men. These units were recruited mainly from draftees physically disqualified for overseas service. The 27th and 31st Infantry when sent to Siberia were configured as AEF regiments, though they were never part of the AEF. Large numbers of men had to be drafted out of the 8th Division to build these two regiments up to AEF strength. This seriously disrupted the 8th Division’s organization.

** Order of Battle of the United States Land Forces in the World War op cit pp. 1372-78; Truman R. Strobridge, A Brief History of the Ninth Marines (Washington DC, Historical Division HQ US Marine Corps; revised version 1967) pp. 1-2; James S. Santelli, A Brief History of the Eighth Marines (Washington DC, Historical Division HQ US Marine Corps; 1976) pp. 1-3; and James S. Santelli, A Brief History of the Seventh Marines (Washington DC, Historical Division HQ US Marine Corps; 1980) pp. 1-5.

April 9, 2023

USMC units in the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) in France

Another interesting excerpt from John Sayen’s Battalion: An Organizational Study of United States Infantry currently being serialized on Bruce Gudmundsson’s Tactical Notebook discusses the role of the US Marine Corps on the Western Front as part of Pershing’s AEF:

“How Twenty Marines Took Bouresches” by Frank E. Schoonover.

Originally published in the Ladies’ Home Journal Vol. 24 No. 1, via Wikimedia Commons

The Fifth Regiment arrived in France in July 1917. Being the fifth regiment of a four-regiment division, it soon found itself relegated to the sidelines and stuck with all the odd jobs such as providing military police details, couriers, and guards. Correctly reasoning that a larger unit would not be so easily pigeonholed, General Barnett [the Marine Corps Commandant] in October 1917 augmented the Fifth Regiment with the newly formed Sixth Regiment and Sixth Machinegun Battalion. The whole force constituted the AEF Fourth Brigade, or half the infantry of the AEF 2nd Division.*

Although the organization of the Fourth Brigade’s infantry regiments was supposed to be the same as that of all the other AEF infantry regiments, it did in fact differ in some details (see Appendix 2.6). Every Marine rifle and machinegun company had two additional sergeants to serve as gas NCOs and the Marines added gas officers to each battalion headquarters. Whether this helped reduce the number of gas casualties is unclear.

Marine enlisted men also tended to be given higher ranks than their Army counterparts. In a Marine regiment a platoon sergeant was not just the senior sergeant in a platoon, he was a gunnery sergeant, ranking as an Army sergeant first class (a rank that the Army awarded only to specialists) and well above a sergeant. Sergeants commanded all four sections in a Marine rifle platoon and this allowed an additional sergeant per half-platoon. The rifle section included two men trained equipped as snipers (enough for one sniper per half-platoon). Two more snipers were in company headquarters. Since 1887 when test results had exposed their poor marksmanship, the Marines had made rifle shooting into even more of a fetish than it had been in the Army. In contrast to the many soldiers sent into battle without even having fired their rifles, no Marine was even allowed overseas if he had not qualified as an expert rifleman or sharpshooter.

To give extra promotion, pay, and recognition (but not leadership responsibility) to the best shots the Marines introduced the rank of corporal (technical). The rank was also given to mechanics, horseshoers, saddlers, teamsters, and five senior operators in the telephone section of the regimental signal platoon to reward technical proficiency. However, despite their important but difficult and thankless duties, Marine cooks only ranked as privates.

[…]

The Marine AEF regiments differed from their Army counterparts in more than just structural details. They had a huge advantage in manpower quality. Except for about 7,100 draftees accepted during the war’s last weeks, the nearly 79,000 Marines who served in the war were all volunteers. About one sixth of these men had joined prior to the war. This was several times the Army’s percentage of pre-war men, even if those who had only National Guard service are included. Many Marine wartime volunteers were college men and included a lot of athletes.

The large number of officer-quality enlisted men persuaded General Barnett to direct on 4 June 1917 that, in future, all officers be appointed from the ranks. This move had the strong backing of Secretary Daniels who favored the practice of commissioning enlisted men. Such a system would be more in line with what the Germans and French were doing. Even the college men would have to have several months’ enlisted service before they could hope for a commission. By then their leadership potential could be properly evaluated. In addition, many pre-war enlisted men of greater age and experience but less education and growth potential could also become officers. Better still, the Marines were mostly infantry. Unlike the Army, they had few service or technical positions into which their best and brightest could be drained. Instead of getting the dregs, Marine infantry regiments got all the best officers and men. They were always kept at full strength with fully trained replacements, despite heavy casualties.**

The high quality men that the Marines were able to contribute to the AEF provoked a good deal of jealousy within the Army in general and from General Pershing in particular. The latter praised the Marines in private but refused to do so in public. Although Pershing had accepted the Fourth Marine Brigade into the AEF, he rebuffed every offer to send Marine artillery to France. The presence of both Marine infantry and artillery in France would have paved the way for the formation of a Marine AEF division. That would have given the Marines much more publicity at Army expense.

Late in the war Pershing relented enough to accept another Marine infantry brigade, the Fifth, which reached France in September 1918. However, although nearly all these Marines had qualified as expert marksmen, he employed them in menial jobs in the rear areas. At the same time, Pershing was rushing thousands of untrained Army recruits into front line combat where they were routinely and needlessly slaughtered.***

* Major David N. Buckner USMC, A Brief History of the Tenth Marines (Washington DC, Historical Div. HQMC; 1981) pp. 16-17.

** Heinl pp. 191-228; and J. Robert Moskin, The Story of the U.S. Marine Corps (New York, Paddington Press Ltd. 1979) pp. 138-139; LtGen William K. Jones USMC(Ret) A Brief History of the 6th Marines (Washington DC, History and Museum Div. HQMC 1987) p 1.

*** Heinl pp. 194-195 and 208-210; Allan R. Millett, Bullard op cit p. 321.

April 7, 2023

Stormtroopers – The German Elite of WW1 – Sabaton History 119

Sabaton History

Published 6 Apr 2023By the middle of the Great War, several nations had begun to experiment with shock troops, and Germany was one of them. The Sturmtruppen were a revolution on the battlefield, for sure, but what did they actually do? What equipment did they carry and use? What were the men actually like? Today we’ll look at all that.

(more…)

Manpower shortages in the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) during WW1

This is an excerpt from Battalion: An Organizational Study of United States Infantry, an unpublished book by the late John Sayen which is being serialized at Bruce Gudmundsson’s Tactical Notebook on Substack. While I haven’t read a lot on the AEF, as I’ve concentrated much more on the Canadian Corps as part of the British Expeditionary Force, I was aware that the American divisions were organized quite differently from either British or French equivalents. The significanly larger division organization — 28,000 men compared to about half that in other allied armies — was intended to give US Army units greater staying power in combat, but it didn’t work out as planned for many reasons:

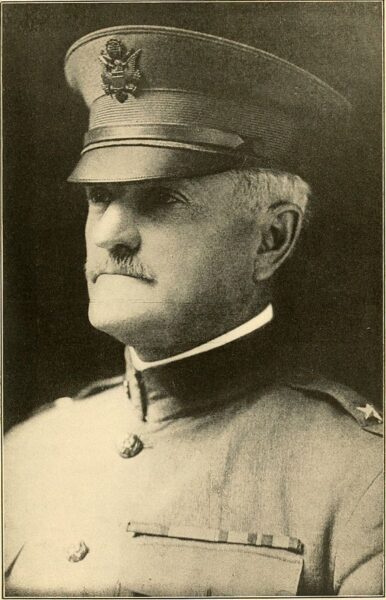

General John J. “Black Jack” Pershing, Commander-in-Chief of the American Expeditionary Forces in France during the First World War.

Image via Wikimedia Commons.

The basic tactical concept behind the square AEF divisions under which the two regiments holding the division’s front line could be relieved by two more regiments to their rear was seriously undermined. The two regiments that were supposed to be resting were the ones that had to man all the work details. When it came time for them to relieve the front-line regiments it was, as historian Allan Millett described it, often a question “of replacing exhausted troops who had suffered casualties with exhausted troops who had not”.

It had certainly not been intended that the infantry serve as labor troops. Such tasks were supposed to have been carried out by separate regiments of pioneers modeled on those used by the French. In the French Army, pioneer regiments were lightly armed infantry serving under corps and army headquarters. They tended to consist of older men and were not the elite assault troops that filled the pioneer platoons in the infantry regiments. Though they could fight when necessary, their main function was to furnish the bulk of the semi-skilled and unskilled labor in the forward areas.

In imitation of this system the War Department raised 37 AEF pioneer regiments. These were organized as AEF infantry regiments without machinegun companies or sapper-bomber, pioneer, or one-pounder gun platoons. Only two of the 29 pioneer regiments to reach France did so before the last three months of the war. One regiment was supposed to go to each army corps and several to each army. However, the AEF pioneers proved to be so badly trained and led (even by AEF standards) that after front line service involving a mere 241 battle casualties most of the pioneers were pulled out of combat to serve as unarmed laborers far to the rear.

It wasn’t just combat casualties that reduced US divisional effectiveness:

Early planning had called for one third of all divisions to serve as replacement depots or field-training units charged with keeping the remaining combat divisions filled with men. The system broke down, however, as heavy losses forced the intended depot divisions to be used as combat units instead. Only six of the 42 AEF divisions to reach France before the Armistice (three more arrived soon afterwards) actually served as replacement or training depots instead of the 14 that were needed.

As an emergency measure, five combat divisions, and later two of the depot divisions, were skeletonized to immediately create urgently needed replacements but, of course, this rendered them useless for either combat or depot duty. Another division had to be fragmented to provide men for rear area support duties and yet another was broken up to flesh out three French divisions. Even in February 1918, (before the AEF had seen serious combat) the four combat divisions in the AEF I Corps were 8,500 men short (mostly in their infantry regiments). The 41st Division, which was the corps’ depot division and charged with supplying those missing men was itself 4,500 men short. By early October 1918, AEF combat units needed 80,000 replacements but only 45,000 were expected before 1 November. At the end of October, the total shortfall had reached 119,690, including 95,303 infantrymen and 8,210 machine gunners. Only 66,490 replacement infantrymen and machine gunners would be available any time soon. For most of the war, AEF combat divisions were typically short by 4,000 men. After August 1918, even divisions fresh from the United States usually needed men. Too many divisions had been organized too quickly.

Of course, the root cause of the manpower problem was even more basic. Men were being used up faster than they could be replaced. The AEF suffered most of its battle casualties between 25 April and 11 November 1918, a period of less than seven months. These combat losses amounted to between 260,000 and 290,000 officers and men, of whom some 53,000 were killed in action or died of their wounds. The rest were wounded or gassed but 85% of these subsequently returned to duty. About 4,500 AEF prisoners of war were repatriated after the Armistice. Five thousand others became victims of “shell shock.” Accidental casualties, including those known to have been caused by “friendly fire” (total friendly fire losses must have been considerable, given the poor state of infantry-artillery coordination), or disease or self-inflicted wounds, far exceeded those sustained in battle.

Two thirds of the more than 125,000 Army and Marine Corps deaths between April 1917 and May 1919 occurred overseas and nearly half (57,000) were from disease. Pneumonia and influenza-pneumonia, which produced the infamous “swine flu” epidemic of 1918, were the chief killers but many victims who became ill before the Armistice did not actually die until after it. Between 14 September and 8 November 1918 some 370,000 cases were reported in the United States alone. Within less than two years between one quarter and one third of the men serving in the US Army had died or became temporarily or permanently disabled by battle, disease, accident, or misconduct. Had such losses continued, the United States might soon have begun to experience the same war weariness and manpower “burnout” that had been plaguing the British, French, and Germans.

With regard to the infantry, the woes of the AEF replacement and training system were much increased by the prevailing belief that because an infantryman needed few technical skills he had little to learn and could be quickly and easily trained from very average human material. Technical arms such as the engineers, signal corps, artillery, and, more significantly, the air corps got the pick of the AEF’s manpower.

The infantry soon became the repository for those deemed unfit for anything better. Many infantrymen saw themselves, and were seen, as cannon fodder. Morale and cohesion were further undermined by the practice of stripping new divisions of men (often before they had even left the United States) to fill older ones. The better men and officers avoided infantry duty to seek less demanding “technical” jobs. Of course, training suffered grievously.

As demands for replacements became more insistent, men who supposedly had received several months’ training were appearing in the front lines not knowing how to load their rifles. Others proved to be recent immigrants who could not speak English. Infantrymen of small physique who might have rendered useful service in non-infantry roles, soon collapsed under the physical burdens placed on them and became liabilities rather than assets. Losses among even good infantry were heavy enough but mediocre infantry melted away at an astonishing rate. Indiscipline, disorganization, and ignorance inevitably increased losses by what must have seemed like a couple of orders of magnitude. These losses were likely to be replaced, if at all, by men of even lower caliber.

Straggling was an especially pernicious problem, which the military police had only limited success in controlling. Even more than actual casualties, it caused some units to simply evaporate. During the Meuse-Argonne offensive, for example, one division reported that it was down to only 1,600 effective men. However, soon after it arrived at a rest area, it reported 8,400 men in its infantry regiments alone.

March 29, 2023

Anti-Tank Chats #7 | Panzerschreck | The Tank Museum

The Tank Museum

Published 2 Dec 2022Join Historian Stuart Wheeler as he details another anti-tank weapon, the Panzerschreck.

(more…)

March 22, 2023

What happened to Colour Sergeant Frank Bourne after Rorke’s Drift?

The History Chap

Published 20 Jul 2022Colour Sergeant Frank Bourne was the senior NCO at the Battle of Rorke’s Drift during the Zulu War of 1879. Superbly played by actor Nigel Green in the 1964 film Zulu, many have wondered why he was never awarded a Victoria Cross when 11 others were. This is the story of what happened to Colour Sergeant Frank Bourne after Rorke’s Drift.

He was actually awarded Britain’s second highest military medal (at the time), the Distinguished Conduct Medal, and ultimately rose from the ranks to become an officer. His military career continued all the way to the First World War, where he was promoted to the rank of Lt. Colonel. Frank Bourne, the last surviving defender of Rorke’s Drift, died in 1945, one day after the Germans surrendered.

(more…)

March 21, 2023

QotD: The elephant as a weapon of war

The pop-culture image of elephants in battle is an awe-inspiring one: massive animals smashing forward through infantry, while men on elephant-back rain missiles down on the hapless enemy. And for once I can surprise you by saying: this isn’t an entirely inaccurate picture. But, as always, we’re also going to introduce some complications into this picture.

Elephants are – all on their own – dangerous animals. Elephants account for several hundred fatalities per year in India even today and even captured elephants are never quite as domesticated as, say, dogs or horses. Whereas a horse is mostly a conveyance in battle (although medieval European knights greatly valued the combativeness of certain breeds of destrier warhorses), a war elephant is a combatant in his own right. When enraged, elephants will gore with tusks and crush with feet, along with using their trunks as weapons to smash, throw or even rip opponents apart (by pinning with the feet). Against other elephants, they will generally lock tusks and attempt to topple their opponent over, with the winner of the contest fatally goring the loser in the exposed belly (Polybius actually describes this behavior, Plb. 5.84.3-4). Dumbo, it turns out, can do some serious damage if prompted.

Elephants were selected for combativeness, which typically meant that the ideal war elephant was an adult male, around 40 years of age (we’ll come back to that). Male elephants enter a state called “musth” once a year, where they show heightened aggressiveness and increases interest in mating. Trautmann (2015) notes a combination of diet, straight up intoxication and training used by war elephant handlers to induce musth in war elephants about to go into battle, because that aggression was prized (given that the signs of musth are observable from the outside, it seems likely to me that these methods worked).

(Note: In the ancient Mediterranean, female elephants seem to have also been used, but it is unclear how often. Cassius Dio (Dio 10.6.48) seems to think some of Pyrrhus’s elephants were female, and my elephant plate shows a mother elephant with her cub, apparently on campaign. It is possible that the difficulty of getting large numbers of elephants outside of India caused the use of female elephants in battle; it’s also possible that our sources and artists – far less familiar with the animals than Indian sources – are themselves confused.)

Thus, whereas I have stressed before that horses are not battering rams, in some sense a good war elephant is. Indeed, sometimes in a very literal sense – as Trautmann notes, “tearing down fortifications” was one of the key functions of Indian war elephants, spelled out in contemporary (to the war elephants) military literature there. A mature Asian elephant male is around 2.75m tall, masses around 4 tons and is much more sturdily built than any horse. Against poorly prepared infantry, a charge of war elephants could simply shock them out of position a lot of the time – though we will deal with some of the psychological aspects there in a moment.

A word on size: film and video-game portrayals often oversize their elephants – sometimes, like the Mumakil of Lord of the Rings, this is clearly a fantasy creature, but often that distinction isn’t made. As notes, male Asian (Indian) elephants are around 2.75m (9ft) tall; modern African bush elephants are larger (c. 10-13ft) but were not used for war. The African elephant which was trained for war was probably either an extinct North African species or the African forest elephant (c. 8ft tall normally) – in either case, ancient sources are clear that African war elephants were smaller than Asian ones.

Thus realistic war elephants should be about 1.5 times the size of an infantryman at the shoulders (assuming an average male height in the premodern world of around 5’6?), but are often shown to be around twice as tall if not even larger. I think this leads into a somewhat unrealistic assumption of how the creatures might function in battle, for people not familiar with how large actual elephants really are.

The elephant as firing platform is also a staple of the pop-culture depiction – often more strongly emphasized because it is easier to film. This is true to their use, but seems to have always been a secondary role from a tactical standpoint – the elephant itself was always more dangerous than anything someone riding it could carry.

There is a social status issue at play here which we’ll come back to […] The driver of the elephant, called a mahout, seems to have typically been a lower-status individual and is left out of a lot of heroic descriptions of elephant-riding (but not driving) aristocrats (much like Egyptian pharaohs tend to erase their chariot drivers when they recount their great victories). Of course, the mahout is the fellow who actually knows how to control the elephant, and was a highly skilled specialist. The elephant is controlled via iron hooks called ankusa. These are no joke – often with a sharp hook and a spear-like point – because elephants selected for combativeness are, unsurprisingly, hard to control. That said, they were not permanent ear-piercings or anything of the sort – the sort of setup in Lord of the Rings is rather unlike the hooks used.

In terms of the riders, we reach a critical distinction. In western media, war elephants almost always appear with great towers on their backs – often very elaborate towers, like those in Lord of the Rings or the film Alexander (2004). Alexander, at least, has it wrong. The howdah – the rigid seat or tower on an elephant’s back – was not an Indian innovation and doesn’t appear in India until the twelfth century (Trautmann supposes, based on the etymology of howdah (originally an Arabic word) that this may have been carried back into India by Islamic armies). Instead, the tower was a Hellenistic idea (called a thorkion in Greek) which post-dates Alexander (but probably not by much).

This is relevant because while the bowmen riding atop elephants in the armies of Alexander’s successors seem to be lower-status military professionals, in India this is where the military aristocrat fights. […] this is a big distinction, so keep it in mind. It also illustrates neatly how the elephant itself was the primary weapon – the society that used these animals the most never really got around to creating a protected firing position on their back because that just wasn’t very important.

In all cases, elephants needed to be supported by infantry (something Alexander (2004) gets right!) Cavalry typically cannot effectively support elephants for reasons we’ll get to in a moment. The standard deployment position for war elephants was directly in front of an infantry force (heavy or light) – when heavy infantry was used, the gap between the two was generally larger, so that the elephants didn’t foul the infantry’s formation.

Infantry support covers for some of the main weaknesses elephants face, keeping the elephants from being isolated and taken down one by one. It also places an effective exploitation force which can take advantage of the havoc the elephants wreck on opposing forces. The “elephants advancing alone and unsupported” formation from Peter Jackson’s Return of the King, by contrast, allows the elephants to be isolated and annihilated (as they subsequently are in the film).

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: War Elephants, Part I: Battle Pachyderms”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2019-07-26.